John Renner • Independent Scholar

Recommended citation: John Renner, “Between the Mountain and the City: Eremitical Life and Death in the Camposanto, Pisa,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 12 (2025). https://doi.org/10.61302/XVJK4030.

Fig. 1. The Camposanto, Pisa (Photo: John Renner).

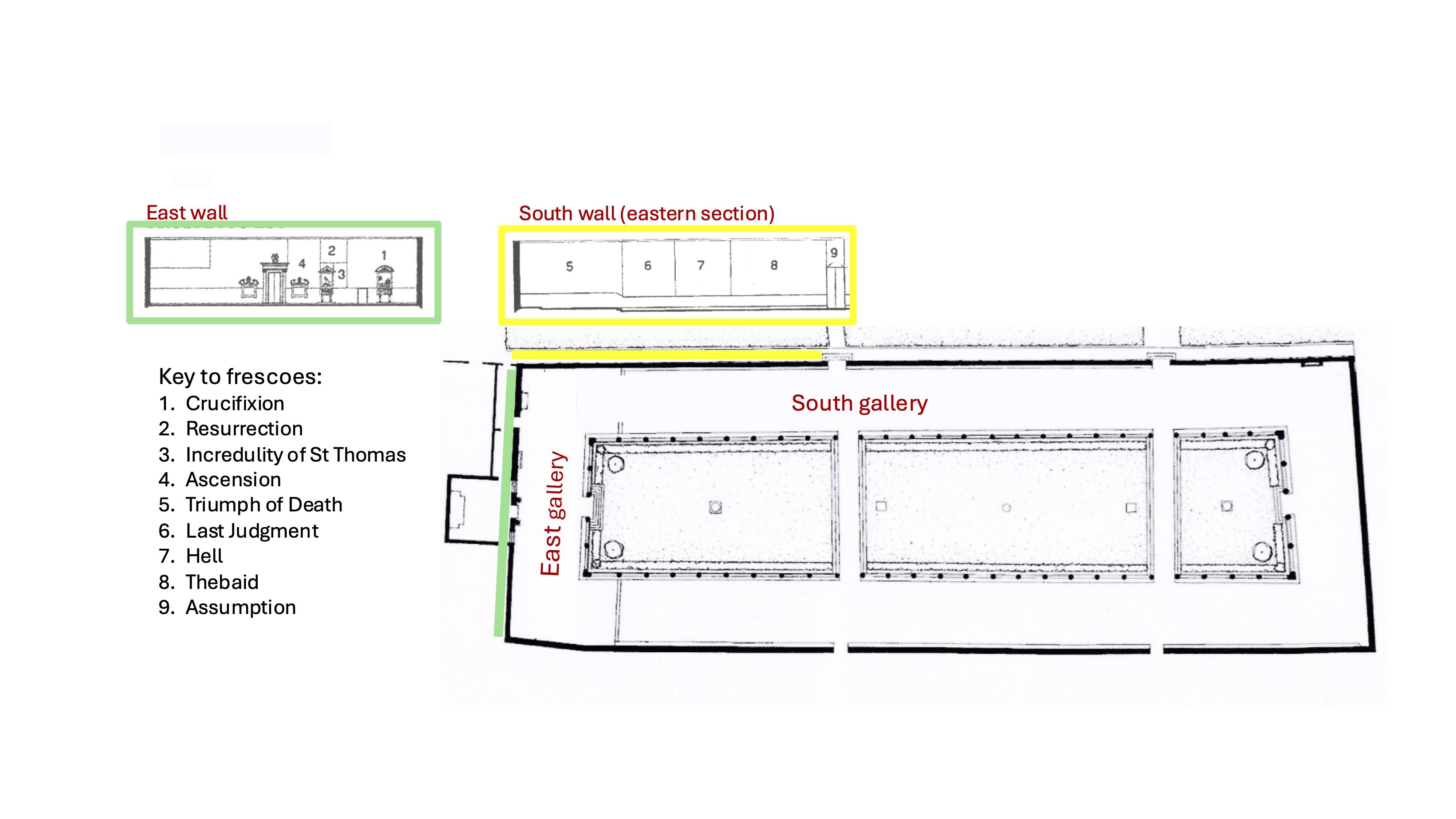

About half a century after its foundation in 1277 the cathedral cemetery of Pisa, the Camposanto, was radically rethought and reconstructed. The first cemetery, consisting simply of an enclosed plot of land with a small church or chapel at its eastern end, was replaced by something much more ambitious and innovative. The burial ground (filled with soil which, according to legend, came from the Holy Land) was reframed in a quadrilateral building like a large elongated cloister, open to the interior and later adorned with Gothic tracery windows, with a broad stone-paved passageway all around it and tomb-chambers set into the pavement.[1] This second Camposanto is essentially the building as we see it today (fig. 1).[2] The frescoing of the interior surfaces of the perimeter walls began in the 1330s in the south-eastern corner of the building (the first part of the Camposanto to be built and roofed) and continued, with interruptions for plague and political upheaval, until the Old Testament cycle across the north wall was brought to a conclusion by Benozzo Gozzoli a century and a half later.[3] This essay is concerned with some of the earliest and best-known of those frescoes: the series consisting of the Thebaid (or Scenes of the Desert Hermits), the Last Judgment and Hell, and the Triumph of Death, attributed to the Florentine painter Buonamico Buffalmacco and datable to between 1336 and 1342.[4] In 2018 – after more than seventy years in temporary accommodation, conservation, and restoration following a catastrophic wartime fire – these long-celebrated paintings were re-installed in their original positions, extending more than 46 metres along the south wall of the Camposanto, from the Porta Regia, then the cemetery’s main entrance from the cathedral piazza, to its eastern end (fig. 2).[5]

Fig. 2. Buffalmacco’s frescoes (c.1336–42) on the southern wall of the Camposanto, Pisa (Photo: John Renner).

The dramatic central scenes of death, judgment and damnation understandably catch most eyes and dominate critical discussion of Buffalmacco’s frescoes. But my focus here is on the noteworthy fact that those spectacular paintings are framed and bookended at either side by images of hermits. There are dozens of hermits on display: over forty in the Thebaid (some depicted more than once, in different scenes from their lives) and five more in the Triumph of Death, in expansive mountainous landscapes evoking the contemporary and the ancient, the familiar and the remote, that extend upwards to the painted borders under the roof beams. This paper will argue that the hermits are crucial for understanding how the frescoes involved their viewers in the epic lessons in personal salvation elaborated in images and inscriptions along this part of the Camposanto. Far from being marginal adornments to the cycle, the painted hermits are central to its designs: artistic, didactic and allegorical. But I will begin with the body of a real hermit – not only because the housing of bodies was, after all, the Camposanto’s raison d’être, but also because of the impact that the presence of this particular body had on the decorative programme as it subsequently developed around it.

The Hermit in the Cemetery: the Tomb of Giovanni Cini

Fig. 3. The tomb of Giovanni Cini, Camposanto, Pisa (Photo: John Renner).

The hermit in question was the beato Giovanni Cini, known as Frate Giovanni “soldato,” who died in 1331 and was the first person to be buried in a monumental tomb in the new Camposanto, when only the eastern and part of the southern galleries had been completed and the walls were still unpainted.[6] The third-century Roman sarcophagus containing Giovanni Cini’s body was installed against the newly-constructed southern wall of the Camposanto, in a prime position adjacent to the main entrance portal (fig. 3).[7] The sarcophagus was framed in a tall gabled tabernacle or baldachin, the original outline of which could clearly be seen on the bare wall when the frescoes were removed after the Second World War.[8] Above the sarcophagus used to be a painted figure of the recumbent hermit, bearded and robed, flanked by a pair of hooded flagellants with flails in their hands. The original decoration of the tabernacle or the area within it is unknown, but Mauro Ronzani’s suggestion that it might have contained scenes from the life of Giovanni is very plausible.[9] The artist Antonio Veneziano was paid for modifications and repairs to the frescoes in 1386, and it was almost certainly then that (for reasons that are unrecorded) the flagellants at the head and feet of the painted effigy of Giovanni Cini were replaced by the two angels to be seen there today, the tabernacle framing his tomb was removed, and more figures of hermits were added to fill the consequent lacunae in Buffalmacco’s Thebaid fresco.[10] The removal of the tabernacle would have drastically reduced the tomb’s physical presence; and today, discreetly embedded into the wall, it’s easily missed among the many other sarcophagi exhibited along the aisles of the cemetery.[11] But for at least fifty years, from the fourth to the ninth decade of the fourteenth century, it would have been much the most conspicuous monument in the Camposanto: a clear sign of the desire of the authorities to promote the hermit as a model of lay piety – and also perhaps as a model “customer” of the new and unfamiliar type of cemetery, which for some years struggled to establish itself as a first choice for wealthy Pisans to be buried in, against the rival attractions of the churches of the mendicant friars and the cathedral itself.[12] Ronzani has aptly termed the burial of Cini a kind of “inauguration” for the newly enlarged Camposanto.[13]

Giovanni Cini had a colourful life history.[14] He was convicted of involvement in an armed attack on the retinue of the new papally-appointed archbishop in 1295 – a murky episode in the periodic conflicts between traditionally Ghibelline (pro-imperial) Pisa and medieval popes – while in the employ of the commune of Pisa as a soldato (soldier or “hired man”). Subsequently released and pardoned, he embarked on an exemplary life of penitence and austerity, firstly taking a role in the charitable offices of the commune and then choosing to live in the abandoned hermitage of Santa Maria della Sambuca, in the Tuscan hills south of Pisa. He and the other frati della penitenzia who joined him there gained the powerful backing of successive Dominican archbishops of Pisa, who favoured them with legal privileges and immunities, while his growing reputation for holiness attracted legacies from well-to-do Pisans to support his community.[15]

As a lay person who adopted an ascetic and eremitical life, Giovanni Cini was very far from unique at that time. The thirteenth and fourteenth centuries have been called a golden age for eremitism in Italy.[16] Every sizeable town had men and women who chose comparable paths, in varying degrees of seclusion. Some, like Cini, attracted followers and formed quasi-cenobitical communities; others lived alone in the countryside or, especially in the case of female recluses, within the urban fabric itself, as anchorites.[17] The mountains of Tuscany and Umbria were dotted with huts and cells of individual hermits, as well as larger communities; Monte Pisano itself, overlooking Pisa, was known as Mons Heremitae.[18] While the choice of eremitical seclusion might seem to imply a rejection of urban life, the example of Giovanni Cini and his frati shows that, on the contrary, one did not cease to be a citizen by retreating to the countryside. The mountain and the city co-existed in mutually beneficial symbiosis. The hermits sustained their lifestyle with the support of the civic and ecclesiastical authorities, as well as alms from private citizens, while the city gained the prestige of being associated with holy ascetics, and the spiritual benefits believed to flow from their prayers. The abundant civic archives of Siena, Pisa’s close Tuscan neighbor, show how formalized, even bureaucratic, this process could be. Daniel Waley has published a document drawn up for the Sienese commune in 1307 of its commitments to give “alms of bread” to monks, nuns, friars and hermits in the city, or within a mile of its walls. Some nine hundred “mouths” are listed, among them eighty-nine people described as hermits, male and female; these urban and suburban anchorites were ranked alongside the regular religious orders, outnumbering any of them except the Franciscan and Dominican friars. They were commonly remembered in private wills, too, with small sums, according to the testator’s means, bequeathed for distribution to each hermit living in the city or within a specified distance of it.[19] A similar picture emerges from bequests to the dozens of hermits and penitents who lived in cells by the walls of Pisa or along the roads leading from the city, whether independently or loosely attached to one or other of the mendicant orders.[20] In the words of André Vauchez, “eremitical sainthood was probably the form of sainthood which, in the Middle Ages, aroused the greatest spontaneous enthusiam among the faithful.”[21] Hermits were ever-present in the urban environment, and the urban consciousness, of medieval Italy.

Sited just beside the entrance to the new Camposanto, Giovanni Cini’s monumental tomb was on the route of every funeral ceremony – and of other processions as well. The feast of the Trinity was celebrated every year in the Camposanto as a major civic occasion, with town criers (banditori) employed by the Commune exhorting citizens to congregate there.[22] Giovanni Cini himself was adopted as a penitential model by the flagellant confraternities which were such a conspicuous feature of lay religiosity in late-medieval Italy; one of them, the Compagnia dei Disciplinati di San Giovanni Evangelista di Porta della Pace, claimed him as their founder (he became known as beato Giovanni della Pace). An avello or tomb niche in the pavement in front of Cini’s sarcophagus served as the common tomb for members of the confraternity, and other groups of lay flagellants also acquired burial spots in the immediate vicinity.[23] These companies of disciplinati were patronized and encouraged by archbishops of Pisa and the mendicant friars, as well as by the lay Operai (directors of the Opera del Duomo) who managed the Camposanto itself and were among the first people to be buried in avelli in the pavement.[24] There are long gaps in the archives of the Opera during the fourteenth century, but two Operai whose wills have survived (drawn up in 1346 and 1390) left detailed instructions that they should be buried in the garb of battuti or flagellants, with an escort of friars and, in the later instance, of members of the Compagnia dei Disciplinati di San Giovanni Evangelista di Porta della Pace as well. As Antonino Caleca has noted, processions of disciplinati must have been a regular sight in the Camposanto, even in its incomplete state.[25] Indeed, with its grand galleries forming a continuous circuit around a central expanse of consecrated ground, it might almost have been expressly designed as a stage for performative rituals of this kind.

Fig. 4. Camposanto ground plan with positions of frescoes (adapted from Orsero 2022).

The painted decoration of the enlarged Camposanto was evidently begun soon after the erection of Giovanni Cini’s tomb, at the building’s south-eastern end – the area known as the presbytery or choir, where the earliest altars were established.[26] The first fresco to be painted on the east wall was Francesco Traini’s large Crucifixion, extending ten metres across the width of the south aisle, followed by Buffalmacco’s scenes of the Risen Christ (the Resurrection, the Incredulity of Thomas and the Ascension) to its left (see the plan, fig. 4).[27] The theme was an obvious one for that location, in a cemetery: Christ’s victory over death. It was then the turn of the south wall to be painted, or at least that part of it which was completed and roofed: precisely the section where Cini’s tomb was situated. We can assume, I think, that a Last Judgment, the central scene in the cycle, would have been a fixed element of the plan from the start; the other scenes, much more unusual in their subject-matter, would have followed conceptually, if not chronologically, from that. Technical evidence sufficient to determine the sequence of execution of Buffalmacco’s frescoes on the south wall is lacking.[28] However, a Trecento visitor entering the Camposanto would normally experience them from west to east – starting from the Thebaid by the entrance and progressing towards the end wall with its altar surmounted by Traini’s Crucifixion, immediately adjacent to the Triumph of Death – and, regardless of their order of execution, that is (in my view) the most natural sequence for reading the frescoes, and the one I will adopt here.[29] Above all, though, it is important to remember that Buffalmacco and his employers did not have a blank wall on which to plan and execute their pictorial programme; it was one already occupied by the body of a much-revered holy hermit, in a large tomb monument decorated with at least one image of him, and probably more. That highly significant presence was bound to be a determining factor on the frescoes subsequently painted around and alongside it.

Hermits in the Wilderness: the Desert Fathers

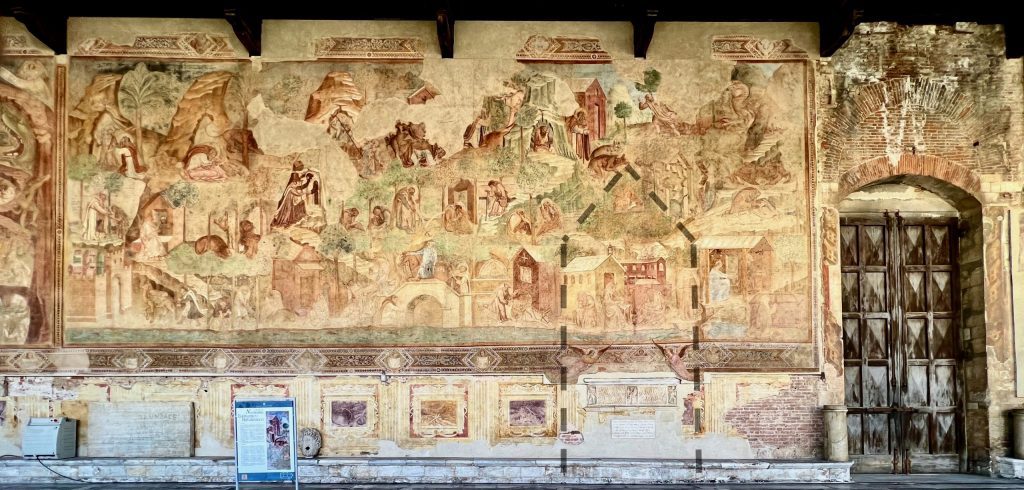

Fig. 5. Buffalmacco, with later additions by Antonio Veneziano, Thebaid (Scenes of the Desert Hermits), fresco, Camposanto, Pisa (broken lines indicate approximate profile of former tomb monument of Giovanni Cini) (Photo: John Renner).

Just a few years after the tomb of Giovanni Cini “soldato” was constructed, the area above and to either side of the tabernacle was painted with Buffalmacco’s scenes from the lives of the early Christian Desert Fathers, further honoring the modern-day hermit by placing him within an ancient lineage of eremitical sanctity.[30] The fresco presents the viewer with an array of hermits in an extensive mountainous landscape, rising steeply from a river teeming with fish along the lower border to a craggy horizon at the top (fig. 5). There is nothing truly comparable in Italian medieval art – certainly not at anything like this scale – until the closely contemporary frescoes contrasting the effects of good and bad government on the long side walls of the Sala dei Nove in the Palazzo Pubblico, Siena, painted by Ambrogio Lorenzetti in 1338–9. Yet unlike the great Lorenzettian panoramas, which recede into vast distances measured by diminishing figures and tiny hilltop towns, Buffalmacco has uptilted his landscape towards the picture plane, to render even the most distant hermits as legible as those closer to the viewer. This anti-naturalistic feature is countered by the liveliness and variety of the figures – human, animal and demonic – who inhabit and travel through this wilderness. The hermits are shown humbly going about their daily tasks of fishing, wood-cutting, weaving mats or baskets, or whittling wooden spoons; sheltering and praying in caves or hillside cells; conversing amongst themselves, or walking along the rocky paths that articulate and interconnect the different levels of the landscape. It is an uncultivated wilderness, the haunt of lions, yet it is also full of verdant groves and luxuriant, fruiting trees that make it a kind of edenic paradise; the lions are notably friendly, lying down at the feet of hermits, or helping them to dig graves for their dead companions.

Like the original Eden, though, this one holds satanic temptations and traps for the unwary – and women are especially to be feared. One hermit is deceived into allowing a female “pilgrim” into his cell, a cave in the mountainside, until he sees through her disguise (she is a demon: her feet are claws, with a raptor’s talons) and expels her at the point of his wooden staff (fig. 6). But there are female saints here too: the Desert Mothers. On the far left of the fresco (below a scene of Anthony Abbot with Paul of Thebes, the “First Hermit”), Mary of Egypt is kneeling to receive the eucharistic host from the abbot Zosimus, who has discovered her living alone in the desert in penitence for her dissolute youth, covered only in her long, unkempt hair (fig. 7). And in the foreground the cross-dressing Saint Marina, who lived in disguise as a monk until she was accused of fathering a child, is sitting outside the monastery from which she has been banished, uncomplainingly taking care of the baby; her true sex (and thus her innocence of the charge) would remain undiscovered until her death (fig. 8).[31]

Fig. 6. Detail of Thebaid, Camposanto, Pisa (Photo: John Renner).

Fig. 7. Detail of Thebaid, Camposanto, Pisa (Photo: John Renner).

Fig. 8. Detail of Thebaid, Camposanto, Pisa (Photo: John Renner).

As has long been known, the episodes depicted in the Thebaid were derived ultimately from the hagiographical legends known as the Vitae patrum, or Lives of the Fathers, about the third- and fourth-century hermit saints who dwelt in the deserts of Egypt and Syria.[32] Though rarely illustrated in Italian art before the fourteenth century, the stories were a staple of moralising sermons, particularly those of the new mendicant orders, charged with preaching to the laity and countering heresy in the rapidly expanding towns and cities of late medieval Europe. Chiara Frugoni and Lina Bolzoni have established multiple connections between Buffalmacco’s frescoes and the writings and sermons of luminaries of the Pisan Dominican convent of Santa Caterina, a noted centre of learning, such as the friars Giordano da Pisa (d.1310), Bartolomeo da San Concordio (d.1347) and Domenico Cavalca (d.1342).[33] Cavalca was the author of the Vite dei santi padri, a vernacular translation of stories from the Vitae patrum that enjoyed widespread popularity.[34] And while that book was not the only source of the episodes depicted in the Thebaid,[35] Cavalca’s prominent position in Pisan cultural life during the 1330s, and his close links with Archbishop Simone Saltarelli (who was also a Dominican), make him a favourite candidate for the role – often hypothesized but rarely identifiable for large-scale religious progammes of this period – of auctor intellectualis of the Triumph cycle.[36] Views differ on how such a figure might have operated in practice, but one can plausibly imagine Cavalca or one of the other senior friars from Santa Caterina providing guidance on the didactic messages the images were intended to convey, and composing or selecting the many inscriptions in verse and prose that once gave names, voices, narrative descriptions, or moralising exegesis to the figures and the scenes painted on the wall.[37]

“These are literally speaking frescoes,” wrote Joseph Polzer, with regard to the way the inscriptions complement the images: “They preach.”[38] Lina Bolzoni has argued that they echo the sermons of Cavalca and his fellow Dominican friars, not only in their content but also in their modes of rhetorical address. “The verse inscriptions aim to transform the painted images into mental images. They seek to charge the painted images with moral meaning and emotional tension so that they will be able to operate on the different faculties of the mind,”[39] in the same way that the friars aimed to do, using vivid examples and memorable phrasing, in their vernacular sermons to the laity.[40] The Thebaid, with its many episodes scattered across the pictorial field, has been compared to a preacher’s tabula exemplorum: a list of stories illustrating particular virtues (humility and patience, say, in the case of Marina, or penitence for Mary of Egypt) with which to enliven a sermon and fix its messages in the minds of its audience.[41] These analogies from sermon studies are pertinent and illuminating; yet the fresco is clearly also more than just a paratactic array of exempla, set out one next to the other with no connection between them, just as it is more than a set of textual illustrations to the Vitae patrum.[42] Buffalmacco and his advisers or overseers have been more artful than that. The figures and incidents are placed within a carefully considered compositional structure with a visual logic of its own, not taken from any written source, in response to the specific demands of the site and the commission.

The scenes around what was once the tomb monument of Giovanni Cini are a case in point. Buffalmacco framed the recently deceased hermit with images of his early Christian forebears, arranged in thematic symmetry, to recall Giovanni’s own penitential withdrawal from urban life. At the lowest level, the tomb was flanked by scenes of temptation resisted in an urban environment: a monk who refused to leave his roadside cell to help a passer-by with a fallen donkey, recognizing him as a demon trying to lure him away from his solitary prayers, and the popular story of the hermit who thrust his hands into a fire rather than yield to the temptation of bodily contact with a woman. Above them, the tabernacle was flanked by two scenes of the ascetic Saint Onophrius, recognizable by his long beard and loincloth of leaves, seen teaching in the Theban desert and then being buried (with the help of two lions) by his disciple and biographer Paphnutius, who discovered him there. And on the top register, above where the pinnacle of Giovanni’s tomb canopy once stood (still visible in the triangular tree-house added by Veneziano when the monument was removed), are two scenes of satanic foes overcome: Saint Anthony Abbot expelling demon assailants from his cell, and the now lost figure of Saint Hilarion, on horseback, fighting a fearsome dragon (fig. 9). The ancient desert saints were placed to form an aureole of time-honored sanctity around the tomb of Giovanni Cini, their modern heir, who likewise abjured the world, the flesh and the devil, starting in the city and withdrawing to the mountains.

Fig. 9. Detail of Thebaid, Camposanto, Pisa (Photo: John Renner).

By presenting the dead body of a revered hermit in the midst of scenes of the Desert Fathers, the Pisan Thebaid was following a pattern which was established by its Byzantine predecessors and would be continued by its Quattrocento successors.[43] The only surviving Italian Thebaid prior to Buffalmacco’s, a folding triptych painted by a Tuscan artist, c.1295, now in Edinburgh, has just such a funeral scene in the foreground of its main panel.[44] The tomb-tabernacle of Giovanni Cini, with the painted image of his recumbent body likewise attended by mourning disciples, would originally have played a comparable role – albeit here not centrally placed, since the monument had already been erected beside the entrance to the Camposanto by the time the wall was marked up for frescoing. Buffalmacco filled the actual, geometrical centre of his composition with something rather different.

Fig. 10. Detail of Thebaid, Camposanto, Pisa (Photo: John Renner).

Right in the middle of the lowest part of the fresco we find a bridge, taking the road on the riverbank over a stream, where a monk is fishing. Crossing it is a well-dressed gentleman in blue, mounted on a horse, pointing ahead but looking back at a hermit standing behind him, with whom he is conversing (fig. 10). The hermit is Saint Macarius of Egypt, and the urbane gentleman on horseback is the Devil (again, the claws on his foot are the give-away). The Devil is revealing his cunning plan to tempt the monks on the road ahead with the delectable liquids in the flasks he is carrying – each one a different variety, to suit every taste. The story was a popular one, included in Cavalca’s Vite patri and in the earlier Golden Legend, though in both texts the flasks are held in the many pockets of the Devil’s coat, and their number is not specified. By showing precisely seven of them arrayed in a row, suspended from a pole, Buffalmacco not only renders them more legible to the viewer but also makes clear what the literary sources only suggest: they are the seven deadly sins, and the Devil is counting on everyone being susceptible to at least one of them (he fails on this occasion – Macarius has schooled his monks too well).[45] The Satan who shows his true shape as the monstrous ruler of Hell in the next fresco is thus prefigured in the Thebaid in the smaller, more urbane form of the potion-seller on the bridge, peddling the very sins for which he will wreak terrible punishment in his own domain.

Immediately above the Devil’s elegantly capped head, on a ledge of rock, is the archetypal memento mori: a skull. Macarius, appearing here in another well-known episode from the Vitae Patrum, has discovered it on the ground and is poking at it with his staff, interrogating it. The skull reveals itself to belong to a pagan whose soul is, as one would expect, in Hell – but not, it transpires, in the deepest part. Below him, the pagan relates, are the Jews; but the deepest pits of all are reserved for Christian sinners who, “having been redeemed by the blood of Christ, think little of so great a price.”[46] Here then, in the central foreground of the fresco, are the first hints – amidst the uplifting examples of eremitical virtue in a desert paradise – of the terrifying themes of death and damnation that await the viewer in the rest of the cycle.

Hell on Earth

Fig. 11. Detail of Thebaid, Camposanto, Pisa (Photo: John Renner).

In the geography of the Thebaid, the river that runs along the bottom of the picture must represent the Nile, and the walled city at the far left doubtless Thebes itself (modern-day Luxor), in whose neighborhood most of the desert saints depicted in the fresco were known to have lived.[47] But as Frugoni observed, and as Trecento viewers could hardly have helped noticing, the landscape closely resembles the locality of Pisa: the river is evocative of the Arno that flows through the city, and the mountains beyond are reminiscent of the Tuscan hills (which, as we have seen, were themselves colonized by hermits such as Giovanni Cini and his followers).[48] Thebes or Pisa, the city was a place of great moral jeopardy; that was as constant a message in the sermons of the Dominican friars as in the teachings of the Desert Fathers. The hermits who have descended from their mountain cells to fish or to join the traffic on the bustling riverbank are therefore risking their souls – and none more so than the monk seen in the left foreground driving his camel, laden with a bundle of the wooden spoons he has carved, into the city to sell in the marketplace (fig. 11). He is about to be swept up into the social and economic life of a crowded metropolis. The spiritual temptations and dangers that await him there may still be unknown to him, but not to us, who can see what is depicted in such horrific detail just the other side of the painted border that cuts off those high city walls that extend to the edge of the fresco. Walking in the direction indicated by the pointing Devil on the bridge, visitors to the Camposanto find themselves following the monk with his camel-load of goods through the gates of the riverside city, heading straight for Hell (fig. 12).

Fig. 12. Hell and Thebaid (details), Camposanto, Pisa (Photo: John Renner).

The medieval Church taught that Hell was a physical place, with a terrestrial location – usually thought to be in the centre of the earth, as Dante placed it in his Commedia, which was completed during the decade before the painting of the new Camposanto was begun.[49] Men and women shared the earth with Satan and his demons, who could and did come up to the surface. Looking at Buffalmacco’s frescoes, it is not hard to imagine the creatures of the underworld crawling up through fissures and crevices in the desert wilderness, perhaps by way of the very caves and mountain gorges sought out by the monks in their attempt to escape from the temptations of the city. In topographical and material terms there is direct continuity between the landscape of the Thebaid and the subterranean realms of Hell in the scene to its left. They are made out of the same stone. Hell’s chambers are hollowed out under the mountains where the lions roam, and the rocky ledges which the hermits use as paths through the wilderness are identical to the ones patrolled by the demons underground, confining the damned to their allotted caverns of torture. Hell and the world depicted in the Thebaid coexist in time as well. Unlike the two brief appearances of Christ on earth, during his historical incarnation and promised Second Coming, Hell is always with us.[50] That is, after all, why demons are able to emerge and torment the living, whether in the Egyptian and Syrian deserts of the early Christian hermit saints or a thousand years later, in Trecento Tuscany.

Fig. 13. Buffalmacco, Last Judgment and Hell, fresco, Camposanto, Pisa (Photo: John Renner).

The vast diagrammatical depiction of Hell takes up almost half of the Last Judgment fresco (fig. 13).[51] The two parts of this central scene in Buffalmacco’s cycle are contained within the same painted frame but they read almost like a diptych, with the Judgment proper on the left-hand side and Hell on the right.[52] The vertical border between them is formed by the gaping hellmouth into which devils armed with grappling hooks are pulling the resurrected bodies of the damned; it is arched like the gate of the city in the Thebaid and inscribed, after Dante, with the words “Lasciate ogni speransa voi che entrate” (“Abandon hope all ye who enter.”)[53] The fresco is remarkable not only for the large amount of space given over to Hell (all the more egregious for the absence of a visible Heaven, as Theresa Holler has noted),[54] but also for the extraordinary prominence of Satan, who is around twice the size of the judging Christ, and much closer to the viewer’s eyeline. As Jérôme Baschet made clear in his authoritative study of medieval images of Hell, these were radical changes to the traditional iconography of the Last Judgment.[55] In line with the findings of other scholars like Frugoni and Bolzoni, Baschet ascribed them primarily to the theological and pastoral culture then dominant in Pisa through the influence of Archbishop Saltarelli and the Dominican friars of Santa Caterina.[56] Equally relevant, though, must be the site-specific fact – unique to the Camposanto – that Hell is placed right next to the stories of the desert hermits painted around the tomb of Giovanni Cini in the Thebaid. That placement had practical consequences, bringing us closer to considerations about how the artist interpreted his brief, translating the instructions of his commissioners into images on the walls.

In conceptual terms the two neighbouring scenes of the Thebaid and Hell balance virtue and vice – but not in the abstract and schematic way of, for example, Giotto’s Virtues and Vices on opposite walls of the Arena Chapel in Padua. In Pisa the virtues are exemplified by hermits, rather than given learned allegorical personification as in Padua; this is a consistently demotic programme. The consequences of failing to follow the hermits’ example are shown graphically in Hell, with its segmented caverns where punishments are tailored to each of the sins of pride, lust, gluttony, sloth, avarice, wrath and envy, as set out in the friars’ confessional manuals.[57] The ethical counter-balance between the virtues and vices in the two neighbouring scenes virtually demands an equivalence of size between them, dictating that Hell, like the Thebaid, should extend the full height of the pictorial surface. The huge figure of Satan himself, by far the largest in the whole cycle, would not have appeared so disturbingly dominant when visually matched – and, as it were, challenged – by the tomb monument of Giovanni Cini, which extended almost to the same height.[58] Satan’s downward sloping upper arms, supported by the verticals of his legs and forearms, even echo the gabled shape of the lost tabernacle. The unprecedented size of Hell in the Camposanto is not anomalous, in other words, when it is viewed as a continuation and pendant of the Thebaid in its original form. There is a visual, as well as a thematic, logic operating here: the two scenes form a kind of diptych of their own.

By this stage we have reached the Last Judgment, and the desert hermits and their disciples have apparently been left far behind, their earthly trials and triumphs over and done with. We have seen them arrayed like a corona around the tomb of the modern-day hermit Giovanni Cini, modelling the penitential life preached in the sermons of the friars, and introducing the great themes of salvation and damnation that would be elevated to eschatological heights at Christ’s Second Coming. But hermits return to the stage to make a final, unexpected appearance at the climax of the cycle, at the easternmost end-point of the famous fresco known as the Triumph of Death.[59]

“Quieta sancta et pura solitudine”: The Hermits on the Mountain

Fig. 14. Buffalmacco, Triumph of Death, fresco, Camposanto, Pisa (Photo: John Renner).

For all its allegorical and other-worldly imagery, the Triumph of Death (fig. 14) is the only one of Buffalmacco’s Camposanto frescoes to be set in the here-and-now. The Thebaid features men and women from the heroic, legendary past of early Christianity; Hell and the Last Judgment are populated by representatives of the whole history of humanity, from Adam and Eve to figures prominent in the public life of fourteenth-century Pisa;[60] but in the Triumph of Death, the cast of human characters is exclusively modern and contemporary. The fashionable dress of the two groups of men and women at either end of the fresco – the mounted hunting party and the seated brigata, or band of pleasure-seekers – enabled Bellosi to date the cycle to the mid 1330s.[61] The corpses of the newly dead heaped on the ground are depicted in all their specifics of costume and ornament to represent distinct fourteenth-century types: the knight, the scholar, the king, the aristocratic lady, the pope, the cardinal, the bishop, the friar, the merchant, his wife, and so forth – male and female, young and old, lay and religious (fig. 15). The hermits on the left-hand side of the fresco may look and dress like the Desert Fathers in the Thebaid but they, too, are living in the same world and the same time as the rest of the people depicted in the Triumph of Death: not a remembered past, nor a prophesied future, but the present moment.[62] They are the modern heirs of the Desert Fathers: men like Giovanni Cini and his followers, or the other hermits inhabiting hills around Pisa – or, as we shall see, the mendicant friars in the city itself, even though no specific order is here depicted. Viewers who (travelling eastward, from the entrance) had already looked at the inspiring historical examples of the first Christian monks, and the dreadful finality of God’s future judgment at the Second Coming, were confronted in the Triumph with urgent questions about how they would conduct their lives now, in the present day. Here, in more shockingly realistic detail than they could ever have seen depicted before, fourteenth-century Pisans came face-to-face with images of their own physical mortality.

Fig. 15. Detail of Triumph of Death, Camposanto, Pisa (Photo: John Renner).

Fig. 16. Detail of Triumph of Death, Camposanto, Pisa (Photo: John Renner).

Fig. 17. Detail of Triumph of Death, Camposanto, Pisa (Photo: John Renner).

Fig. 18. Detail of Triumph of Death, Camposanto, Pisa (Photo: John Renner).

This complex fresco, containing multiple interwoven narrative strands, is structured around clearly defined groups of people, separated spatially by elements of landscape. First to be seen, on the right, are the brigata of ten young people in a pleasant orange grove – a Garden of Love – conversing, making music, holding animals for petting or falconry, and generally dallying, oblivious to the imminent onslaught of the bat-winged, scythe-wielding hag, Death (fig. 16).[63] Buffalmacco’s deployment of naturalism is here carefully modulated. The decorative quality of the pleasure-seekers’ garden alerts us to how artificial and insubstantial is their leafy bower: the vegetation of the lawn is rendered in patterns no less geometrical than those adorning their gorgeous robes and dresses, as if it were a tapestry. Above this fools’ paradise, angels and demons wheel in aerial dogfight over the souls of Death’s latest victims (fig. 17).[64] A few fortunate individuals are being carried away from the melee by angels; the fate of one corpulent cleric is in the balance, caught in a tug-of-war between an angel and a devil; but most of the somatomorphic (or body-shaped) souls are claimed by demons and borne off to the fiery mountain that dominates the upper centre of the fresco.[65] Meanwhile in the foreground, to the left of the pile of corpses, is a piteous group of the decrepit, the leprous and the maimed, painted with an unflinching eye for the disfigurements of age and disease, imploring Death to put an end to their sufferings (fig. 18).

Emerging through a wooded ravine or defile in the rocky landscape just behind them comes an elegant hunting party, consisting of ten men and women mounted on horses and two retainers on foot, one holding a hound in leash and the other carrying a brace of mallards presumably caught on the wing by the falcons now perched, hooded, on the gauntlets of three of the riders. They are moving towards the left, dragging our attention with them, but have been brought to a sudden stop. The path is barred by three open coffins, positioned at the front of the picture plane so as to be almost spilling out their contents over the painted frame, into the space occupied by the viewer (fig. 19). The coffins display bodies in various stages of decomposition: an ermined scholar with bloated belly; a king, with desiccated flesh stretched over his bones; and a ragged skeleton with eyeless sockets turned towards us, meeting and holding our gaze.[66] The hermit standing above them, addressing the horrified riders, transforms this elaborate version of the popular medieval legend of The Three Living and the Three Dead into an image of penitential preaching.[67] His role is different to that of his counterparts in the Thebaid, where (as we have seen) the Desert Fathers and their stories can be said to function as exempla for the homilies summarised in the inscriptions. The principal hermit in the Triumph is delivering the sermon himself (once spelt out on the scroll he is holding), and his exempla are the three corpses laid out below him.

Fig. 19. Detail of Triumph of Death, Camposanto, Pisa (Photo: John Renner).

This preaching hermit recalls two highly unusual frescoes showing Franciscan saints beside a skeletal corpse, painted by Giotto and his workshop, which must have been important sources, whether directly or indirectly, for Buffalmacco. In the chapter house of the Santo in Padua, the tomb church of Saint Anthony of Padua, are figures of saints and prophets standing in fictive niches, probably painted in the first decade of the fourteenth century. Next to Saint Anthony himself is a skeleton, badly worn and barely legible, towards which the saint is pointing. The inscriptions on the scrolls held by both figures (with quotations from Ecclesiastes and Job respectively) once made clear that this pair of images was a memento mori sermon on human mortality.[68] A slightly later fresco in the Lower Church of San Francesco in Assisi shows Saint Francis next to a crowned skeleton propped up against a wooden board; the saint is holding up one hand in a gesture of speech, addressing the viewer with what is surely a similar message, though here there is no inscription.[69] Both Franciscan frescoes, like Buffalmacco’s greatly expanded version in the Camposanto, are in close relationship with large Crucifixions, linking the reminder of the frailty of human life, exemplified by the skeletons, with Christ’s victory over death on the Cross. The interchangeability of the hermit and the friar in these variations on the theme is a corollary of the spiritual affinity with the Desert Fathers claimed by the mendicant friars (and not just those, like the Carmelites and the Augustinian Hermits, with specifically eremitical origins), who aspired to lead the vita contemplativa of hermits even while engaged in the vita activa of combatting heresy and sin among the urban populace.[70] The sermons of the thirteenth-century Archbishop of Pisa, Federigo Visconti (in office 1253–77) – during whose tenure the Camposanto was begun – are full of praise for the way the new orders of mendicant friars combined the contemplative and active lives; but he also recognized the spiritual risks they were running in choosing to work amidst the material temptations of the city.[71] Preaching in commemoration of an Augustinian friar who was appointed to an archbishopric, Visconti spoke of how the deceased man “was obliged to descend from the mountain of contemplation to the city of action,” where “perhaps something of worldliness (aliquid terrenitatis) stuck to his feet,” that would now have to be burned away in the fires of Purgatory.[72]

Fig. 20. Detail of Triumph of Death, Camposanto, Pisa (Photo: John Renner).

The hermit by the coffins in the Triumph of Death has also come down “from the mountain of contemplation” to fulfil the duties of the vita activa by preaching to lay men and women. Behind him, the rocky path he has descended climbs up through trees to where his fellow monks can be seen, grouped around their hilltop monastic hermitage (fig. 20). Two white-bearded elders are outside the entrance, one of them hunched over a book while his companion stands gravely beside him, leaning on wooden crutches, with rosary beads on his belt. Two younger monks are out on the mountainside; one is milking an obligingly tame hind and another is peering down the path, curious to see what’s going on below.[73] For all the inhospitability of the terrain, the community of hermits lives in harmony with the created world around them. A pheasant struts undisturbed in front of the church, a squirrel and a rabbit forage nearby, and two young stags bask on a sunlit slope. (Only further down the cliff does nature seem to mimic the ways of fallen humankind, in the vividly-observed detail of a marten with a pigeon in its jaws.) The peaceful rural scene was described in a verse held by an angel in the frame below, beginning with the line “Quieta sancta et pura solitudine,” which might be rendered as follows:

O holy quiet, and purest solitude,

How sweet you are to those that know you well!

Of flesh or of demonic care foresworn,

They do most good who hide themselves away,

Away from all that’s bitter in this world.[74]

Fig. 21. Detail of Triumph of Death, Camposanto, Pisa (Photo: John Renner).

The tranquility of this eremitical paradise, though, is undercut and seemingly threatened by the bizarre and fearsome sight just beyond it. Behind and to the right of the hermitage rises a high volcanic mountain, flames spouting from its openings and fissures, into which winged demons are thrusting naked men and women: souls plucked from the bodies of the dead and bound for Purgatory or for Hell (fig. 21).[75] The proximity of the hermitage to the fiery mountain is clearly deliberate. The monks in this modern Thebaid may have withdrawn to the wilderness, but their hilltop hermitage affords them a very clear view of the consequences of a sinful life – a view denied to those who spend their time in the illusory garden of love with the idle young people, or in the valley of worldly pursuits with the aristocratic hunting party. This gives the sermonizing on death and repentance by the venerable hermit by the coffins a special authority, born of reading, contemplation and prayer, within sight of the mountain where souls are fed to the flames. And it puts him and his brother hermits on the hillside above in a particular position with regard to the viewers of the frescoes, as well: the position of the mendicant friars, whose sermons expounded, in the churches, piazzas and public spaces of Trecento Pisa, the urgent messages that are here given such vivid visual embodiment – and whose prayers were widely believed to be especially efficacious for the souls of the dead.

Conclusion

Buffalmacco’s frescoes were planned and produced at a particular moment in the history of Pisa, the 1330s, when there was a period of unusually close collaboration between the communal government of Pisa, the lay officials of the Opera del Duomo, the cathedral chapter headed by Archbishop Simone Saltarelli, and his fellow Dominican friars in the convent of Santa Caterina.[76] This temporary conjunction of secular and ecclesiastical interests, combined with the intellectual input of the friars, resulted in a unique and highly ambitious commission. It was a commission evidently overseen by learned clerics but aimed squarely at lay men and women, the intended occupants of the new civic cemetery. Before any of the frescoes had been painted, though, the much-revered local hermit, Giovanni Cini, died; and it evidently suited all of those directing the project to promote him as a model of lay devotion, giving him a prominent tomb in the only part of the Camposanto then built. It must have seemed a natural, opportune step to choose the early Christian desert saints – who figured as the heroes of so many of the friars’ sermons, and whose lives had just been translated into the vernacular by Domenico Cavalca at Santa Caterina – to be placed nearest the entrance, around the tomb of the modern hermit. From that moment, hermits were established as major actors in the unfolding painted drama, providing its predominant figuration of the virtuous life. The artist employed to execute the commission, Buffalmacco – an idiosyncratic and highly inventive Florentine, trained in the new Giottesque naturalism – was able to deploy the hermits in creative ways so that they became a leitmotif running through the programme. They shift roles and registers between the ancient and the modern, between realism and allegory, bookending the cycle and linking its component parts.

If the hermits start the cycle, in the Thebaid, as painted exempla from the sermons of the friars, they end it, in the Triumph of Death, as the preachers themselves (fig. 22). These latter-day hermits live, like the Friars Preacher of Santa Caterina, in a monastic retreat which nonetheless enables them to play a full part in giving spiritual guidance to lay men and women in mortal danger among the distractions and temptations of worldly life. The modern Thebaid in the Triumph of Death is an allegory of how the vita contemplativa and the vita activa can be combined. The quieta sancta et pura solitudine the hermits have created for themselves is situated between the infernal fires of the mountain behind and the putrescent corpses in the coffins below. It could hardly be a more apt visual metaphor for the Camposanto itself: a cloistered place of repose in the heart of the sinful city, but also – as a building whose sole purpose was to house the bodies of the dead – a site where fourteenth-century Pisans found reflected their deepest anxieties about mortality and the afterlife.

Fig. 22. Detail of Triumph of Death, Camposanto, Pisa (Photo: John Renner).

I would like to thank the editors and the reviewers for their valuable advice. Thanks also to Geoffrey Nuttall.

References

| ↑1 | For the building history see Emilio Tolaini, “Campo Santo di Pisa: progetto e cantiere,” Rivista dell’Istituto nazionale d’archeologia e storia dell’arte 17 (1994): 101–46; Antonino Caleca, “Costruzione e decorazione dalle origini al secolo XV,” in Clara Baracchini and Enrico Castelnuovo (eds.), Il Camposanto di Pisa (Turin: Einaudi, 1996), 13–48; Mauro Ronzani, Un’idea trecentesca di cimitero: la costruzione e l’uso del Camposanto nella Pisa del secolo XIV (Pisa: Edizioni Plus, 2005); Margherita Orsero, L’âge d’or del Camposanto di Pisa: pittura e committenza nella prima metà del Trecento (Rome: Viella, 2022), 25–35. On the legend of the holy soil see the essays in Michele Bacci, David Ganz and Rahel Meier (eds), Journeys of the Soul: Multiple Topographies in the Camposanto of Pisa (Pisa: Edizioni della Normale, 2020), esp. David Ganz, “Campo santo, campi dipinti: The Legend of the Earth and the Spaces of the Camposanto’s Early Fresco Decoration,” in Journeys of the Soul, 65–110. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The main later alteration to the Camposanto was the insertion of the domed Dal Pozzo chapel at its eastern end in the late sixteenth century. |

| ↑3 | A useful summary with timeline is available online at Written Camposanto: The Pisan Cemetery through the Eyes of Chroniclers, Artists and Travelers, authored by a team led by David Ganz at the University of Zurich: https://dlf.uzh.ch/sites/camposanto/timeline/. |

| ↑4 | The authorship of Buffalmacco has been generally accepted since the publication of Luciano Bellosi, Buffalmacco e il Trionfo della morte (Turin: Einaudi, 1974). Attribution to the Pisan painter Francesco Traini had previously been argued by Millard Meiss, “The Problem of Francesco Traini,” The Art Bulletin 15 (1933): 97–173, at 127–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.1933.11408632. On the dating of the frescoes (of which there is no direct documentary record) see Caleca, “Costruzione e decorazione,” 20–26; Orsero, L’âge d’or, 37–64 (and see Orsero’s volume for the fullest and most up-to-date bibliography). |

| ↑5 | On 27 July 1944 a stray Allied artillery shell hit the Camposanto and ignited its wooden roof, necessitating a major rescue operation to detach the surviving frescoes from the walls: see Cathleen Hoeniger, “The Camposanto of Pisa in the Wake of World War Two: Loss and Discovery,” in Holly Flora, Sarah Wilkins (eds.), Art and Experience in Trecento Italy (Turnhout: Brepols, 2018), 313–28. |

| ↑6 | On Cini’s tomb see Chiara Frugoni, “Altri luoghi, cercando il Paradiso (il ciclo di Buffalmacco nel Camposanto di Pisa e la committenza domenicana),” Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa 18 (1988): 1557–1643, at 1639–40; Caleca, “Costruzione e decorazione,” 22–25, 29–31; Orsero, L’âge d’or, 70–74. |

| ↑7 | Fulvia Donati, “Sarcofagi per corpi santi e la ‘politica museale’ di Lasinio nel lato est del camposanto di Pisa,” Bollettino storico pisano 65 (1996): 87–114, esp. 89–93. The sarcophagus is currently embedded flush into the wall, showing only its front face, but may originally have protruded from the wall on brackets or pillars (Donati, “Sarcofagi,” 92). The monument was probably similar to that of the Dominican friar and beato, Giordano da Pisa (d.1310), whose tomb-chest, likewise a repurposed classical sarcophagus, is now under the high altar of Santa Caterina, Pisa, but was originally located on the nave wall within a baldachin or niche: Joanna Cannon, Religious Poverty, Visual Riches: Art in the Dominican Churches of Central Italy in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2013), 103–05 and 371, n.104. |

| ↑8 | See Frugoni, “Altri luoghi,” Plate 328, 2; and Ganz, “Campo santo, campi dipinti,” fig. 34. |

| ↑9 | Ronzani Un’idea trecentesca, 136–7. The monument might well have included a representation of the dead man’s soul being carried to heaven by angels, as was common in funerary contexts, e.g. on the sculpted tomb of Archbishop Simone Saltarelli (d. 1342) in Santa Caterina, Pisa. |

| ↑10 | Frugoni, “Altri luoghi,” 1641–42; Ronzani, Un’idea trecentesca, 111, 114, 140. The conventional name for the subject-matter of the fresco, a Thebaid, refers to the Theban desert in Upper Egypt where many of the Desert Fathers dwelt. |

| ↑11 | The covered galleries of the Camposanto were rearranged in the early nineteenth century as a lapidary museum: Fulvia Donati, “ll reimpiego dei sarcofagi: profilo di una collezione,” in Baracchini and Castelnuovo (eds.), Camposanto, 69–92. |

| ↑12 | Even after the huge mortality of the Black Death the Camposanto was not in demand for burials, necessitating a decree by the governing Anziani in 1349 to ban further burials in the overcrowded cathedral, in order to prevent the Camposanto from being “neglected and falling into disuse” (“essere trascurato e uscire dall’abitudine”): Ronzani, Un’idea trecentesca, 60. On lay demand for burials in mendicant churches see Caroline Bruzelius, Preaching, Building, and Burying: Friars in the Medieval City (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2014), esp. 150–60. |

| ↑13 | Ronzani, Un’idea trecentesca, 47. |

| ↑14 | On the life of Giovanni Cini (who was not officially beatified until 1857) see Ronzani, Un’idea trecentesca, 111–40; Frugoni, “Altri luoghi,” 1634–39. |

| ↑15 | Ronzani, Un’idea trecentesca, 121–30. On the three successive Dominican archbishops of Pisa between 1299 and 1342, an unprecedented period of dominance by one order, see Ronzani, “Note e osservazioni sui vescovi mendicanti in Italia centrale fino alla metà del secolo XIV,” in Dal pulpito alla cattedra: i vescovi degli ordini mendicanti nel ‘200 e nel primo ‘300. Atti del XXVII Convegno internazionale, Assisi, 14-16 ottobre 1999 (Spoleto: Centro italiano di studi sull’alto Medioevo, 2000), 133–65 (esp. 158–65). |

| ↑16 | Carlo Delcorno, “Modelli agiografici e modelli narrativi: tra Cavalca e Boccaccio,” Lettere italiane 40 (1988): 486–509 [repr. in Delcorno, Città e deserto: studi sulle “Vite dei santi padri” di Domenico Cavalca (Spoleto: Fondazione Centro italiano di studi sull’alto Medioevo, 2016), 137–64], at 494–95. |

| ↑17 | For an overview see Mario Sensi, “Anchorites in the Italian Tradition,” in Liz McAvoy (ed.), Anchoritic Traditions of Medieval Europe (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press, 2010), 62–90. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781846157868-008. |

| ↑18 | Delcorno, “Modelli agiografici,” 495; Bert Roest, “The Franciscan Hermit: Seeker, Prisoner, Refugee,” in Jitse Dijkstra and Mathilde Van Dijk (eds.), The Encroaching Desert: Egyptian Hagiography and the Medieval West (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2006), 163–89, at 166 (giving the variant mons eremiticus). https://doi.org/10.1163/9789047411628_010. |

| ↑19 | Daniel Waley, Siena and the Sienese in the Thirteenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 135–36. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511583865. |

| ↑20 | Mauro Ronzani, “Penitenti e ordini mendicanti a Pisa sino all’inizio del Trecento,” Mélanges de l’Ecole française de Rome. Moyen-Age, Temps modernes 89 (1977): 733–41, at 741. https://doi.org/10.3406/mefr.1977.2422. |

| ↑21 | André Vauchez, Sainthood in the Later Middle Ages, trans. Jean Birrell (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 333 (see also 190–97). |

| ↑22 | Ronzani, Un’idea trecentesca, 29–30. |

| ↑23 | It’s usually assumed that Giovanni Cini was himself a flagellant, but Ronzani has argued that this aspect of his cult dates from the 1340s, after his death: Un’idea trecentesca, 134–40. |

| ↑24 | The first two altars on the eastern wall, dedicated to All Saints and the Trinity, were founded respectively by the Operai Giovanni Rossi (d.1333) and Giovanni Scorcialupi (d.1337), who were buried in front of Traini’s Crucifixion: Caleca, “Costruzione e decorazione,” 20. |

| ↑25 | Caleca, “Costruzione e decorazione,” 24–25. Caleca also draws attention to a document of 1343 which refers to an “uscio di Campo Santo unde intravano li battuti”: 44, n.125. |

| ↑26 | Ronzani, Un’idea trecentesca, 62–64. |

| ↑27 | Caleca, “Costruzione e decorazione,” 20–22. On the Crucifixion, see Linda Pisani, Francesco Traini e la pittura a Pisa nella prima metà del Trecento (Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2020), 180–83. |

| ↑28 | The rescue operation to remove the frescoes after WWII apparently destroyed any evidence about how the intonaci overlapped: Frugoni, “Altri luoghi,” 1643. For what the restorers did discover see Leonetto Tintori, “Note sulla tecnica, i restauri, la conservazione del ‘Trionfo della Morte’ e di altri affreschi dello stesso ciclo del Camposanto Monumentale di Pisa,” Critica d’arte 58 (1995): 53–62. The technical evidence is well discussed by Orsero, L’âge d’or, 65–70. |

| ↑29 | Scholars who believe the Thebaid was the first painting in the cycle include Joseph Polzer, “The Role of the Written Word in the Early Frescoes in the Campo Santo of Pisa,” in World Art: Themes of Unity in Diversity. Acts of the XXVIth International Congress of the History of Art, ed. Irving Lavin, 3 vols (University Park PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1989), 2:361–72, at 364; and Ronzani, Un’idea trecentesca, 47. Others assume or argue an opposite, left-to-right sequence: e.g. Alessandra Malquori, Il giardino dell’anima: ascesi e propaganda nelle Tebaidi fiorentine del Quattrocento (Florence: Centro Di, 2012), 85; Maria Laura Testi Cristiani, The Human Comedy in the Triumph of Death by Buffalmacco in the Camposanto of Pisa (Pisa: Società Storica Pisana, 2017), 57–65. There seems to be consensus, though, that Buffalmacco had most creative freedom in the eastern parts of the cycle, particularly in the Triumph of Death, which may be another reason to suppose that scene to have been painted last. |

| ↑30 | On the thematic correspondence between the tomb and Buffalmacco’s fresco see Frugoni, “Altri luoghi,” 1634–43; Malquori, Giardino, 81–88. Stefano Fiorentino’s Ascension was also painted over the entrance portal adjacent to Buffalmacco’s Thebaid, probably in the early 1340s; on this fresco, destroyed in 1944, see Orsero, L’âge d’or, 74–95. |

| ↑31 | On the figures and stories in the fresco see Frugoni, “Altri luoghi,” 1585–1633; Eva Frojmovic, “Eine gemalte Eremitage in der Stadt: die Wüstenväter im Camposanto zu Pisa,” in Hans Belting and Dieter Blume (eds.), Malerei und Stadtkultur in der Dantezeit: die Argumentation der Bilder (Munich: Hirmer, 1989), 201–14 (with annotated plan of the fresco at 204); Alessandra Malquori, “Luoghi e immagini nelle Storie degli Anacoreti di Pisa,” in Maria Monica Donato and Massimo Ferretti (eds.),‘Conosco un ottimo storico dell’arte …’: per Enrico Castelnuovo: scritti di allievi e amici pisani (Pisa: Edizioni della Normale, 2012), 97–104; Malquori, “L’immagine della morte e l’edificazione attraverso l’immagine nelle Storie degli anacoreti del Camposanto di Pisa,” in Bacci, Ganz and Meier (eds.), Journeys of the Soul, 143–63; Malquori (ed.), with Manuela De Giorgi and Laura Fenelli, Atlante delle Tebaidi e dei temi figurativi (Florence: Centro Di, 2013), 28–32. |

| ↑32 | Salamone Morpurgo, “Le epigrafi in rima del ‘Trionfo della morte,’ del ‘Giudizio universale e inferno’ e degli ‘Anacoreti’ nel Camposanto di Pisa,” L’Arte 2 (1899): 51–87 (at 71–84); Ellen Callmann, “Thebaid Studies,” Antichità viva 14 (1975): 3–22; Frugoni, “Altri luoghi,” 1585–1633; Frojmovic, “Eine gemalte Eremitage.” |

| ↑33 | Frugoni, “Altri luoghi.” Lina Bolzoni, “Un codice trecentesco delle immagini: scrittura e pittura nei testi domenicani e negli affreschi del Camposanto di Pisa,” in Antonio Franceschetti (ed.), Letteratura italiana e arti figurative: atti del XII Convegno dell’Associazione internazionale per gli studi di lingua e letteratura italiana, 3 vols (Florence: L.S. Olschki, 1988), 1:347–56. Bolzoni, “La predica dipinta: gli affreschi del Trionfo della morte e la predicazione domenicana,” in Baracchini and Castelnuovo (eds.), Camposanto, 97–114. Bolzoni, The Web of Images: Vernacular Preaching from its Origins to St Bernardino da Siena, trans. C. Preston, L. Chien (Aldershot UK, Burlington VT: Ashgate, 2004), 11–40. |

| ↑34 | Domenico Cavalca, Vite dei santi padri, ed. Carlo Delcorno, 2 vols (Florence: Edizioni del Galluzzo per la Fondazione Ezio Franceschini, 2009). See also Delcorno’s many studies on Cavalca’s Vite, collected in Delcorno, Città e deserto. |

| ↑35 | For texts other than Cavalca’s where the episodes in the Pisan Thebaid can be found, including the Golden Legend of Jacopo da Voragine (also a Dominican), see the list (from Frojmovic’s unpublished Master’s thesis) in Frugoni “Altri luoghi,” 1606, n.92. |

| ↑36 | Caleca, “Costruzione e decorazione,” 23; Ronzani, Un’idea trecentesca, 47. See also Marcello Ciccuto, “Giunte a una lettura esemplare di Buffalmacco nel Camposanto di Pisa,” Italianistica 21 (1992): 407–24. |

| ↑37 | The inscriptions, most now lost or illegible, were mainly in the vernacular, on scrolls held by figures within the frescoed scenes and along the lower borders. The Thebaid also has inscriptions written over areas of the pictorial field adjacent to the figures. Additionally, there were Latin inscriptions on scrolls held by figures along the top borders. The vernacular verse inscriptions, as transcribed in a fifteenth-century manuscript in the Biblioteca Marciana, were published in 1899 by Morpurgo, “Le epigrafi.” |

| ↑38 | Polzer, “Written Word,” 366; see, similarly, Frugoni, “Altri luoghi,” 1561 (“una predica figurata”) and Bolzoni: “La predica dipinta.” |

| ↑39 | Bolzoni, Web of Images, 31 |

| ↑40 | On Dominican preaching to the laity see Carlo Delcorno, Giordano da Pisa e l’antica predicazione volgare (Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 1974); Eliana Corbari, Vernacular Theology: Dominican Sermons and Audience in Late Medieval Italy (Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 2013). |

| ↑41 | Frojmovic, “Eine gemalte Eremitage,” 207; Malquori, Giardino, 87. |

| ↑42 | Compare with the manuscript that is the main focus of the recent study by Denva Gallant, Illuminating the Vitae patrum: The Lives of the Desert Saints in Fourteenth-Century Italy (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2024). |

| ↑43 | On the motif, see Manuela De Giorgi, “La dormizione dell’eremita,” in Malquori (ed.), Atlante, 189–200; also pp. 16–20 of Malquori’s introduction to the same volume. |

| ↑44 | Malquori, “La Dormizione dell’eremita di Grifo di Tancredi,” in Malquori (ed.), Atlante, 217–23; Amelia Hope-Jones, “Images of the Desert, Religious Renewal and the Eremitic Life in Late-Medieval Italy: A Thirteenth-Century Tabernacle in the National Gallery of Scotland” (PhD diss., University of Edinburgh, 2019), 81–84. |

| ↑45 | The verses once on the fresco referred to “le ’mpolle de’ peccati mortal’ che fan l’om molle” (Morpurgo, “Le epigrafi,” 78). |

| ↑46 | Jacobus de Voragine, The Golden Legend: Readings of the Saints, trans. William Granger Ryan, 2 vols. (Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993) I:90. The dialogue between Macarius and the skull must once have been inscribed on the scrolls depicted in the fresco. |

| ↑47 | For more detailed referents see Cathleen Hoeniger, “Reading the Landscape in the Camposanto Thebaid,” in this edition of Different Visions. https://doi.org/10.61302/PNYB4756. Diane Cole Ahl’s argument, in “Camposanto, Terra santa: Picturing the Holy Land in Pisa,” Artibus et Historiae 24 (2003): 95–122 (esp. 99, 106, 108), that the Thebaid, in common with “nearly every scene” in the Camposanto, was designed to evoke Jerusalem, the legendary origin of the soil in the cemetery, is unconvincing on visual grounds alone (among others pointed out by Ganz, “Campo santo, campi dipinti,” 70, 105). See also Serena Romano’s comments on the legend of the holy soil (to which neither the inscriptions nor the frescoes make any explicit reference) in her review of the volume Journeys of the Soul in Convivium 9.2 (2022): 126–29.Diane Cole Ahl’s argument, in “Camposanto, Terra santa: Picturing the Holy Land in Pisa,” Artibus et Historiae 24 (2003): 95–122 (esp. 99, 106, 108), that the Thebaid, in common with “nearly every scene” in the Camposanto, was designed to evoke Jerusalem, the legendary origin of the soil in the cemetery, is unconvincing on visual grounds alone (among others pointed out by Ganz, “Campo santo, campi dipinti,” 70, 105). See also Serena Romano’s comments on the legend of the holy soil (to which neither the inscriptions nor the frescoes make any explicit reference) in her review of the volume Journeys of the Soul in Convivium 9.2 (2022): 126–29. |

| ↑48 | Frugoni, “Altri luoghi,” 1624. |

| ↑49 | On the topography of the Commedia and its literary antecedents see Alison Morgan, Dante and the Medieval Otherworld (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990). |

| ↑50 | The evolution of medieval beliefs about death, judgment and the afterlife is charted in the classic study by Caroline Walker Bynum, The Resurrection of the Body in Western Christianity, 200–1336 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995). |

| ↑51 | Hell extends the full height of the fresco and is about 7 metres wide, compared with about 8.5 metres for the width of the Judgment proper. |

| ↑52 | Michelangelo da Volterra, the author of a late-fiftenth-century poem entitled Le mirabile et inaldite belleze e adornamenti del Campo Sancto di Pisa, treats Hell and the Last Judgment as two separate pictures: cited in Jérôme Baschet, Les justices de l’au-delà: les représentations de l’enfer en France et en Italie, XIIe-XVe siècle (Rome: Ecole française de Rome, 1993), 309. |

| ↑53 | Morpurgo, “Le epigrafi,” 64. |

| ↑54 | Theresa Holler, Jenseitsbilder: Dantes Commedia und ihr Weiterleben im Weltgericht bis 1500 (Berlin; Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2020), 94–7. See also Jérôme Baschet, “Triomphe de la mort, triomphe de l’enfer: les fresques du Camposanto de Pise,” L’Écrit-voir 8 (1986): 4–17; Friederike Wille, Die Todesallegorie im Camposanto in Pisa: Genese und Rezeption eines berühmten Bildes (Munich: Allitera, 2002), 49–78. |

| ↑55 | See the extensive analysis in Baschet, Les justices, 293–349. Baschet detects some of these innovations “in embryo” (en germe) in previous Italian Last Judgments but finds no precedents for the radical autonomy of Hell and its disproportionate scale (308–11). |

| ↑56 | Baschet, Les justices, 327–49. |

| ↑57 | Baschet, Les justices, 304–08. |

| ↑58 | The figure of Satan has probably been restored more often than any other in the cycle; the fresco had to be repainted due to game-playing or vandalism by stone-throwing youths from as early as the fourteenth century: Baschet, Les justices, 626–27; Ganz, “Campo santo, campi dipinti,” 74. |

| ↑59 | The fresco’s conventional name, which is also often used (misleadingly) for the cycle as a whole, derives of course from the arresting personification of Death wielding her great scythe. See the detailed analysis in Wille, Die Todesallegorie. |

| ↑60 | See, most recently, Orsero, L’âge d’or, 46–58, identifying the layman being led to salvation in the foreground of the Last Judgment as the powerful Count Bonifazio Donoratico della Gherardesca (d.1340). |

| ↑61 | Bellosi, Buffalmacco, 41–54. |

| ↑62 | Vasari’s identification of the hermit standing over the coffins as Saint Macarius is still sometimes repeated but is without foundation, as Frugoni pointed out (“Altri luoghi,” 1564). He is unnamed in the inscription (Morpurgo, “Le epigrafi,” 57), and unlike Macarius in the Thebaid he has no halo; he is an anonymous holy hermit. |

| ↑63 | Penny H. Jolly, “Symbolic Landscape in The Triumph of Death: The Garden of Love and the Desert of Virtue,” Politeia 21 (1985): 27–42. This insightful article situates the landscapes of the frescoes in their literary traditions. |

| ↑64 | On the iconography of the struggle between angels and demons for possession of souls see Virginia Brilliant, “Envisaging the Particular Judgment in Late-Medieval Italy,” Speculum, 84 (2009): 314–46, at 324–28. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0038713400018066. |

| ↑65 | For the theological implications of picturing souls as somatomorphic see Bynum, Resurrection, 291–330. |

| ↑66 | The (lost) rhymed inscription addressed the viewer directly: “Tu che mi guardi et si fiso mi miri…” (“You who look at me and so fixedly gaze on me…”): Morpurgo, “Le epigrafi,” 60. |

| ↑67 | On The Three Living and the Three Dead see Paul Binski, Medieval Death: Ritual and Representation (London: British Museum Press, 1996), 134–8; Ashby Kinch, “Image, Ideology, and Form: The Middle English Three Dead Kings in its Iconographic Context,” Chaucer Review 43 (2008): 48–81. https://doi.org/10.1353/cr.0.0008. The fundamental study of the theme’s iconographical development in Italy remains Chiara Settis Frugoni, “Il tema dell’Incontro dei tre vivi e dei tre morti nella tradizione medioevale italiana,” Atti della Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, 13 (1967): 145–251. The addition of the hermit figure was an Italian innovation, first appearing in the late thirteenth century, which Frugoni interprets as transforming the original dialogue between the living and the dead into an explicit stimulus for penitential meditation (166–82). |

| ↑68 | The frescoes were discovered and published, along with the inscriptions that were then still legible, by Bernardo Gonzati, La Basilica di S. Antonio di Padova, 2 vols (Padua, 1852), 1:265–70. |

| ↑69 | See Frugoni, “Il tema dell’Incontro,” 149; Janet Robson, “The Changing Imagery of Saint Francis in the Basilica of San Francesco in Assisi,” in Sanctity Pictured: The Art of the Dominican and Franciscan Orders in Renaissance Italy, ed. Trinita Kennedy (Nashville: Frist Center for the Visual Arts; London: Philip Wilson Publishers, 2014), 19–31 (at 29); Wille, Die Todesallegorie, 114–117. |

| ↑70 | The balance between the two forms of life was a constant source of tension among the Franciscans: see Roest, “The Franciscan Hermit.” On the eremitical origins, real and mythical, of the Augustinians and Carmelites, see Frances Andrews, The Other Friars: the Carmelite, Augustinian, Sack and Pied Friars in the Middle Ages (Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK; Rochester, NY: Boydell Press, 2006). |

| ↑71 | On Visconti see Mauro Ronzani, “Visconti (di Pisa), Federico,” in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 99 (2020): https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/federico-visconti_%28Dizionario-Biografico%29/. |

| ↑72 | “Verumtamen quia sic magnus prelatus erat, opportebat eum descendere de monte contemplationis in Civitate actionis ubi forte aliquid terrenitatis suis pedibubus adherat, ut sic ‘ligna fenum et stipulam super-hedificasset’ [1 Cor. 3:12] que quasi per ignum purgatorii sunt cremanda”: cited in Alexander Murray, “Archbishop and Mendicants in Thirteenth-century Pisa,” in Murray, Conscience and Authority in the Medieval Church (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 105–62, at 150 (the translation of the first phrase is Murray’s, the second mine). |

| ↑73 | The genre scene of the hermit milking the hind appears also among the sinopie for the Thebaid, but not in the finished fresco. It seems that it was decided to save this touching glimpse of domestic communion between man and beast for the “modern Thebaid” in the Triumph of Death. |

| ↑74 | “Quiëta sancta et pura solitudine,/ Quanto se’dolce ad quei chi ti conoscono!/ Di carne o di demon’ sollicitudine,/ Tanto piú servono quanto piú s’imboscano,/ Privi della mondana amaritudine”: Morpurgo, “Le epigrafi,” 61 (my translation). |

| ↑75 | The concept of Purgatory had a long ancestry in patristic and theological writings but was given doctrinal definition only in 1274, at the Second Council of Lyons: see Jacques Le Goff, The Birth of Purgatory, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984), 284–88. I will be analysing its relevance to the Triumph of Death in a future study. |

| ↑76 | Mauro Ronzani, “Il ‘cimitero della chiesa maggiore pisana’: gli aspetti istituzionali prima e dopo la nascita del Camposanto,” Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa. Classe di Lettere e Filosofia, 18 (1988): 1665–90, esp. 1687–90; Orsero, L’age d’or, 58–62. |