Rosalyn Saunders • University of Glasgow

Recommended citation: Rosalyn Saunders, “Becoming Undone: Monstrosity, leaslicum wordum, and the Strange Case of the Donestre,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 2(2010). https://doi.org/10.61302/CJPZ6330.

In this article, I explore the Donestre, a monstrous race found in the Wonders of the East, through examining text-image relationships as well as the possible meanings of the race’s very name. Although the textual description is matter-of- fact in tone, when coupled with the imagery, these two mediums work to “undo” the race through the exposure of not only their monstrously deformed bodies, but also their perverse use of human language, which has the effect of destabilizing their gender and sexual identities. I employ Judith Butler’s notion of gender- language performativity and postulate that the Donestre “becomes undone” through normative conceptions of gender, which construct a differential between the human and the less-than-human. According to Judith Butler, gender is culturally determined via the concrete laws, rules and policies that constitute the legal instruments through which persons are made regular, and most importantly recognisable.[1] Gender is not a static biological fact but a dynamic cultural production; it is a performance, a “kind of doing, an incessant activity performed . . . one does not ‘do’ one’s gender alone. One is always ‘doing’ with or for another.”[2]

A norm can only exist through the recognition and acceptance of particular traits that become more associated with either the male or the female in accordance with cultural expectations. This differential ultimately undermines the viability of the Donestre’s individual personhood, and they are “undone”[3] through the performance of recognisably human language and their description as frifteras/frihtere, which actively places them with the lowest criminal levels of Anglo-Saxon society. This framework suggests that although the Donestre are located at the fringes, they are truly terrifying because they affect the monstrous transition from “out there” (where the monsters live) to “right here” (within the communal and local space). Their behavior is reminiscent of the criminal element within society, and thus the Donestre present the reader-viewer with a familiar and stereotyped figure as a sign or warning, echoing Augustine’s familiar account, that one must be constantly vigilant and on guard against immorality, for such behavior is not only unchristian and unnatural, but also threatens society as a whole.[4] The Donestre is one of two anthropophagus (man-eating) races located in an area near the Red Sea by the anonymous author of the Anglo- Saxon Wonders of the East text, which survives as three illuminated manuscripts: Cotton Vitellius A. xv, Cotton Tiberius B. v, and Bodley 614, respectively.[5] The Vitellius manuscript is written in Old English and has been dated to the late tenth century; the Tiberius written in Latin and Old English has been dated to the mid-eleventh century; and the third surviving manuscript, Bodley 614, is written exclusively in Latin and has been dated to the twelfth century.[6] The Vitellius Wonders is bound with other Old English literary works, notably Beowulf, Judith, and The Letter of Alexander to Aristotle; the Tiberius is compiled in a miscellany with scientific works, computational tables, maps and genealogical lists; and the Bodley is bound with astrological charts and calendars.[7] The story of the Donestre appears in all three manuscripts, as well as in the Anglo-Saxon Liber monstrorum, the latter extant in five manuscripts all dating from the ninth or tenth centuries.[8] Furthermore, the textual descriptions in the Wonders manuscripts and the Liber monstrorum follow a similar pattern: the Donestre are hybrids; they use human language to name the traveller and inquire after his acquaintances; and once trust is established, the Donestre devour all of the traveller except the head, over which they weep.

In contrast to the Wonders, however, the Liber monstrorum does not name the race; rather it refers to them as “a race of mixed nature on an island in the Red Sea.”[9] Interestingly, the word-form “Donestre” is unattested and occurs only in the Wonders manuscripts, which suggests that either the Vitellius author, or an author of an earlier version from which the Vitellius was copied, coined it. Although the Wonders names the race and provides a lengthy description of its unsavory behavior, no explanation or translation of the word-form is provided, which in this text is unusual. For example, the Conopenas, a race of dog-heads, is translated in Old English as healf-hundingas (half-dogs) and in Latin cenocephali (dog-heads). The name, Homodubii, is explained as referring to a race of twylic/twimen (doubtful/double) people. In addition, a reader with knowledge of Latin would read Homodubii as a compound of homo (man, people) and dubium (doubt/double), respectively; and similarly identify Hostes, the Donestre’s anthropophagus counterpart, as Latin for “enemy.”[10] The translation of Donestre, however, is more complex, as it is an unattested form in Old English and its origins are not traceable to Latin. As a further complication, the race is not included in Isidore of Seville’s Etymologiae, which otherwise provides a helpful list of etymologies for many of the monstrous races included in both the Wonders and Liber monstrorum.[11] The absence of a translation and linguistic clues in the text, therefore, suggests that the form was possibly easily identifiable to the Anglo-Saxon reader, and a common knowledge of Old English should suffice for this purpose. Alternatively, in order to convey inhuman, exotic, or marvellous properties, the author may have newly invented the form, and a translation was therefore unnecessary as the race is beyond any level of human understanding. When considered alongside the other named races in the manuscripts, however, it becomes apparent that the naming-system of the Wonders seems to be linked to either appearance or behavior, and considering that the textual description of the Donestre is comparatively lengthy and similar in all three manuscripts, the reader should, theoretically, be able to discern meaning from the text.

The full textual description of the Donestre, as translated by Andy Orchard, reads:

Then there is an island in the Red Sea where there is a race of people we call Donestre, who have grown like soothsayers from the head to the navel, and the other part is human. And they know all human speech. When they see someone from a foreign country, they name him and his kinsmen with the names of acquaintances, and with lying words they beguile him, and after that eat him all up except for the head, and then sit and weep over the head.[12]

In his formative discussion of the Donestre, Jeffrey Jerome Cohen proposes that the anthropophagy of the Donestre forms the focus of the narrative, and argues that the Wonders use anthropophagy to explore selfhood’s limits.[13] Cohen’s reasoning is that the Donestre transubstantiates the man via the consumption of his flesh, a monstrous act that breaks down the discrete identities of both the Donestre and traveller; they, quite literally, become one flesh.[14] Accordingly, this moment of plurality forces the Donestre “to realise the fragility of autonomous self-hood, [and] how much of the world it excludes in its panic to remain selfsame, singular, stable.”[15] This tension between “the self” and “the foreign” mapped by Cohen onto the body of the Donestre is persuasive, and Nicholas Howe similarly observes that the Donestre’s attempt to assimilate the traveller via the incorporation of his flesh can never be complete, for “elsewhere” the foreign cannot be fully consumed and therefore becomes an object of regret and fear.[16] The Donestre’s anthropophagy and inability to fully consume the traveller are indeed intrinsic to the narrative of exclusion. However, I believe that anthropophagy is not the sole means by which the Donestre “becomes undone” and excludes—and is excluded in return by the world. Rather, I propose that the monstrous and malicious nature of the race, as well as the meaning of its name, is understood not only through its hybrid body and anthropophagy, but also by the perverse performance of recognisably human behavior, both bodily and verbal, in both the text and accompanying pictorial imagery.

The interaction between the Donestre and the traveller in the text is remarkable as, although the Donestre are hybrids, their behavior towards the traveller is recognisably human, and this semblance of humanity is maintained until the devouring of the traveller. However, the characteristics displayed by the Donestre, though human, are overwhelmingly negative, and the fundamental theme of the textual description is that of deception. The Donestre are liars and their ability to feign congeniality by naming the traveller and his kin is pretence, merely leaslicum wordum (lying words) used to beguile him and consume his flesh. Their otherworldly linguistic and soothsaying abilities are explained by their appearance: they are part frifteras/frihtere from the head to the navel, and part human below. The author, however, does not elaborate further and the reader-viewer is left pondering what exactly he means by swa frihtere (like a soothsayer), translated as quasi diuini and quasi diuinum (divine, prophetic) in the Latin texts of both Tiberius and Bodley respectively,[17] as well as how the contemporary Anglo-Saxon reader-viewer would have interpreted this.

Tom Tyler has suggested that the description of the Donestre as part soothsayer functions to signal to the reader-viewer that “an element of these monstrous creatures is markedly different from the human portion…[and so] this polyglot race exemplifies particularly well, then, the mixed nature of monstrosity described by Foucault.”[18] He further contends, citing Foucault, that the mixed nature of such creatures present “a monstrous, ancestral figure to the deviants of today, drawing our attention both to qualities that contemporary abnormal individuals inherit,”[19] a reading he later applies to Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Tyler’s analysis is impressive, particularly his linking of mixed monstrosity with immorality and criminality; the monstrous not only transgresses natural limits and classifications, but also violates the laws of society, disturbing civil, canon or religious law.[20] Although fully persuasive, Tyler’s study still leaves room for expansion. Why were the authors of the Liber monstrorum and Wonders of the East preoccupied with expressing the race’s strangeness and almost otherworldly nature/appearance? What did “like a soothsayer” mean to the Anglo-Saxon reader-viewer, and is this meaning somehow connected to their name, in the manner of other named races in the Wonders whose names are descriptive of their appearance or behavior?

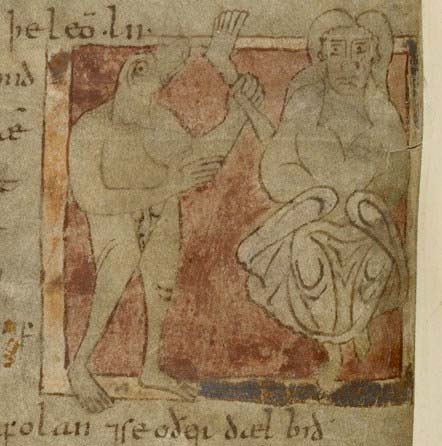

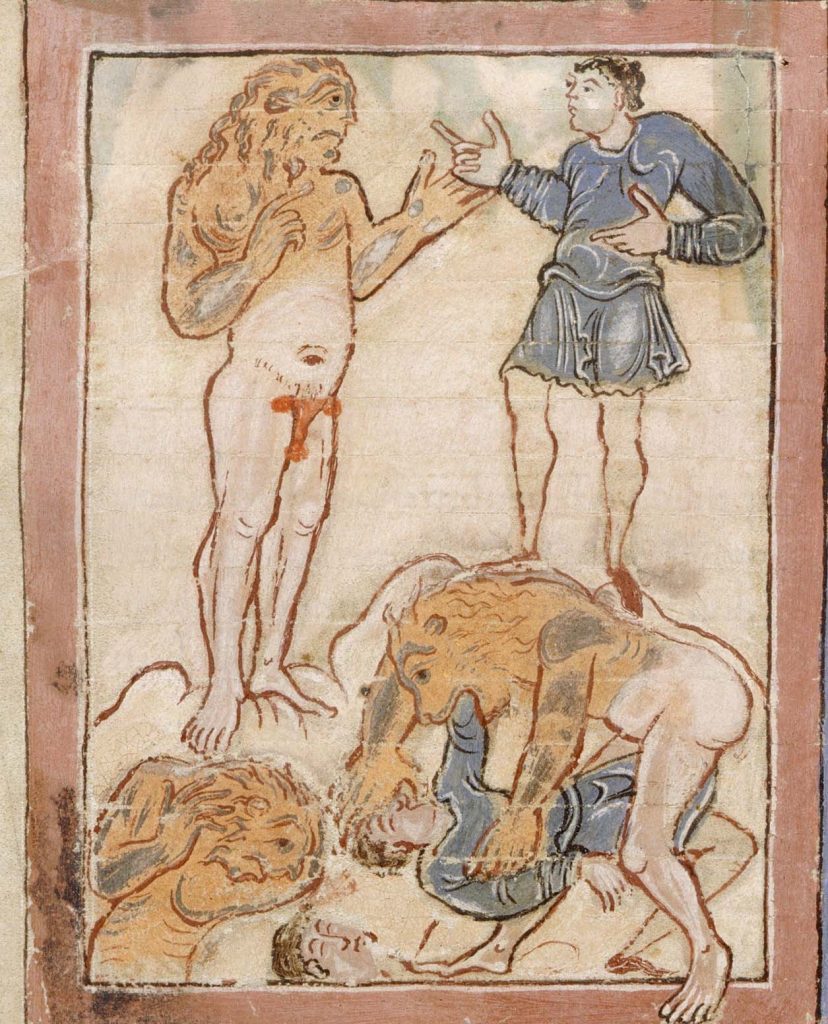

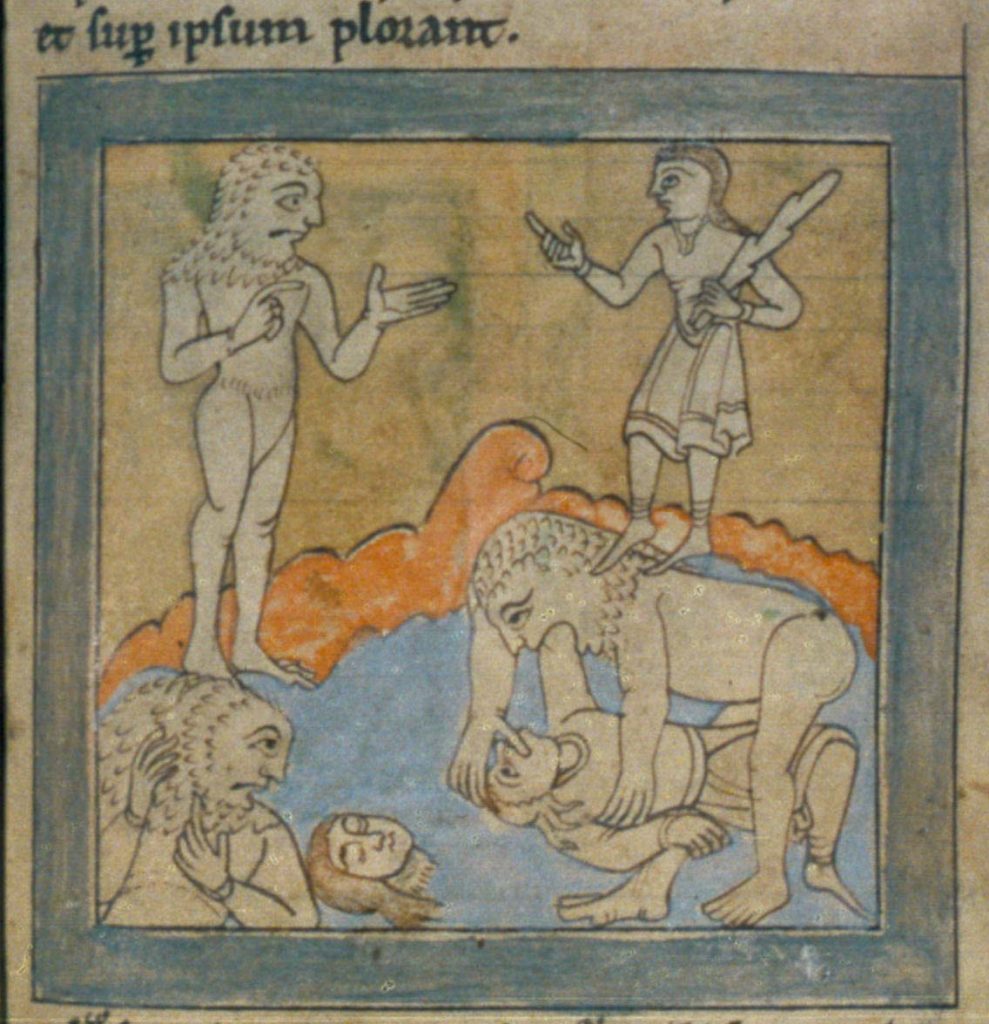

The medieval illuminators provide us with a possible interpretation of frifteras/frihtere as synonymous with wildness and the bestial by giving the Donestre an animalistic countenance. The Donestre is recognisably human on some level, but as Geoffrey Galt Harpham observes, “the overwhelming impression of monstrousness corrupts this familiarity and grades [the Donestre] towards a principle of primitivism, or bestiality.”[21] The bestiality of the Donestre is stressed in all three illuminations via their animalistic heads, but there is nothing particularly primitive about the Donestre in either text or picture. Rather, the text-image relationships in all three manuscripts depict a skilled being, able to overcome its victims without considerable physical effort or injury to itself. For example, in the Vitellius image (Figure 1), the Donestre is depicted as a beast-headed, naked man brandishing a human leg and foot towards a fully clothed individual to the right of the frame. Despite its bestial appearance and seemingly savage behavior, it is obvious that the Donestre has beguiled its previous victim with its linguistic prowess, and consumed all but the limb (and presumably the head though the illumination does not include it). The brandishing of the limb towards the seated figure underscores the inevitability of his/her demise, as the Donestre will, without doubt, overpower and devour him/her as it has others before. The Tiberius and Bodley (Figures 2, 3) reinforce the danger posed by the Donestre as both illuminations provide a narrative series of three scenes conforming to the textual description within one frame. The first shows the naked and bestial Donestre beguiling the traveller; the second, the Donestre devouring the traveller; and the third, the Donestre weeping over the head. In all three manuscripts, the text-image relationships emphasize the inevitability of the traveller’s demise as he/she is invariably devoured.

Fig. 1. Donestre. London, British Library, MS Cotton Vitellius A. xv., fol. 103v (detail) (© The British Library Board, All Rights Reserved)

Fig. 2. Donestre. London, British Library, MS Cotton Tiberius B. v., fol. 83v (detail) (© The British Library Board, All Rights Reserved)

Fig. 3. Donestre. Oxford, Bodleian Library, Bodley 614, fol. 43v (detail) (© The Bodleian Library, University of Oxford)

Mary C. Olson, however, contends that the detailed textual description of the Donestre encourages the reader-viewer to engage in an implied and hypothetical relationship in which s/he is invited to imagine encountering such beings.[22] Olson reasons that the reader / imaginary traveller, equipped with the knowledge that the Donestre will try to fool you by speaking your language, will recognize the Donestre’s real agenda and respond appropriately to avoid this outcome.[23] The notion that the reader / traveller will be able to out-smart the Donestre in an imaginary encounter is plausible, but the text-image relationships, which Olson does not consider in her study, suggest otherwise, considering that the Donestre is the dominant and controlling figure in all three illuminations. From the evidence of the imagery, the traveller succumbs to the Donestre because it is a talented and charming being despite its animalistic appetites and appearance.

The animalistic nature of the Donestre is communicated further by the figure’s nakedness in the three illuminations, which John Block Friedman considers a sign of “wildness and bestiality—of the animal nature thought to be characteristic of those who lived beyond the limits of the Christian world.”[24] Following Friedman, Paul Freedman similarly observes that because of “this tension between the fully clothed human (i.e. rational and either Christian or potentially Christian) and hapless savage (naked, ignorant, subsisting of raw food), the monstrous races exemplify the image of the ‘medieval other.’”[25] This schematisation segregates the clothed and Christian human being from the naked, raw food eating, and possibly non-Christian monstrous race/individual in order to produce a differential between the human and the less-than-human. Freedman, however, persuasively rejects the tendency to “treat [the] alien or Other as if they were stable terms denoting complete and consistent rejection when in fact there were degrees of marginality so, that seemingly contradictory positions could be held simultaneously.”[26] Such is the case with the Donestre: its nakedness may be representative of an animalistic nature and reinforces its status as ‘different’ to the fully clothed, non-anthropophagus, and, presumably, Christian traveller; but at the same time, it also exposes the Donestre’s recognisably human body with its primary markers of sexual identification: human genitals.

The Donestre’s exposed body not only complements the text by presenting the Donestre as part human, but also assigns its body primary markers of sexual identification, which are clearly male in both the Vitellius and Tiberius images. In contrast, the Bodley Donestre displays no obvious primary or secondary markers of sexual identification: its body is completely androgynous despite its similarity in other respects to the Tiberius illumination. The Tiberius Donestre on the surface level appears unambiguously male, with its bright red penis, and in the first beguiling image, the Donestre’s body and bright red genitals express masculine sexual energy and potency not mandated by the text. Ironically, however, the Tiberius Donestre’s secondary sex characteristics (an extremely hairy and muscular body) confuse this reading, because although such features make the figure more masculine, as we shall see presently, they do not ultimately pertain to whether it is actually male.

Sexual identification of the Vitellius Donestre is comparatively more difficult as it is not endowed with obvious protruding genitalia like the Tiberius image but rather has a sizeable “V” shape in the groin area. In a recent study, Asa Mittman and Susan Kim propose that the figure has clear and easily visible male genitals,[27] and Kim, in an earlier study, posits that the Vitellius illustrator “pairs the monster with a female figure unmentioned by the text, thus providing a context of sexual difference to underscore the exposure of a clearly male monster.”[28] Mittman and Kim’s sexual identification of the Vitellius Donestre as male is visually plausible, but given the accompanying text, the illuminator was not compelled to make the Donestre externally masculine because the plural pronoun hi is consistently used to describe all the monstrous races in the Wonders, and being neuter, it could refer to either masculine or feminine grammatical gender. Further, the Vitellius Donestre is described as part frifteras in appearance, a word that is unrecorded elsewhere, including the Tiberius manuscript, which uses the Old English frihtere.[29] It is therefore possible that the Vitellius frifteras is a derivation of the agent-noun frihtere, which is inflexionally marked masculine in Old English, and a masculine textual reading for the Vitellius Donestre would indeed complement the clearly masculine figure in the illumination. However, it is important to note that although frihtere is morphologically masculine in Old English, there is no attested feminine form (frihtestre), and no evidence in Old English to suggest that soothsaying was an exclusively male occupation.[30] Nevertheless, the Donestre in the Vitellius and Tiberius figures may be read as externally masculine with male genitals, and Kim further argues that the juxtaposition of the naked Donestre in Vitellius with the fully clothed female figure underscores not only its maleness and cannibalistic behavior, but its exposed male genitals also convey a sense of male sexual violence.[31]

A sense of male sexual threat is also experienced by the reader-viewer of the Tiberius manuscript whose naked Donestre, with his vibrant and large penis, reaches out his arm and hand to touch the traveller’s hand (Figure 2). This act ostensibly suggests friendly intimacy, but the Donestre’s nakedness adds a threatening—but also erotic and sensual— character to the scene, which would perhaps have been especially disturbing for an Anglo-Saxon reader-viewer in light of the fact that the Donestre is a hybrid, and both figures are clearly male. The interaction between the Donestre and traveller in the Tiberius image is highly ambiguous as the Donestre’s nakedness and touch has a twofold interpretation: it could convey, on the one hand, contrived fraternal intimacy, with the Donestre’s nakedness alluding to its preoccupation with the flesh— namely the traveller’s flesh. On the other hand, the bright red genitals heighten the Donestre’s sexuality and could suggest the threat of imminent male-male sexual violence. When considered alongside the text, the Donestre become truly horrifying as the text-image relationships expose not only the Donestre’s monstrously hybrid body, but also its monstrous sexual ambiguity, as “it is through the body that gender and sexuality become exposed to others, implicated in social processes, inscribed by cultural norms, and apprehend their social meanings.”[32] The bodies of the Donestre may be externally masculine, but an Anglo-Saxon reader-viewer would have found these visual figures deeply unsettling and disturbing: they appear male, but at the same time, their monstrosity renders them “not quite male.”

During the Middle Ages, cultural norms were also informed by medical theory that was dependent upon classical authorities, and the body was believed to be composed of a complex humoral system, onto which law and religion attempted to impose a regulating dichotomy of feminine and masculine. Following Aristotle, the male was believed to be conceived in the right hand side of the womb, and the female in the left. Accordingly, the female body was thought to be cold and moist in contrast to man’s heat and dryness.[33] Men were thought to be ‘active’ (energetic, brave, strong, resilient, honest, moderate, self- controlled, and rational), and women, ‘passive’ (weak, soft, gentle, nurturing, kind, timorous, and modest). This dichotomy of active and passive had important consequences for male and female physiology and spirituality. Owing to their ‘active’ status, men were destined for the political and social challenges of the social sphere, but ‘passive’ femininity on the other hand became increasingly associated with the domestic sphere and childrearing. Theorists accordingly rationalized that the male was the measure of all things, and therefore that the female was a deviation from the norm, the Other.[34] She was governed by her sex, which being ‘naturally’ imperfect and inferior, resulted in the construction of the wayward feminine as deceptive, manipulative, impatient, inconstant, quick- tempered, immoderate in appetite, sexually rapacious and consequently an aberration in comparison with the idealized male. However, this is arguably an over-simplification of complex gender-roles and behaviors in the Middle Ages, because despite the construction and upholding of a regulating dichotomy, it is clear that such conventions were defied. Those who undermined gender boundaries were not only regarded with suspicion and hostility, but were also considered morally and spiritually weak and ultimately a threat to society, as evidenced in Old English literature.

The poet of the Old English Precepts sets his poem as a series of instructions given from father to son, but it is evident that the reader is meant to cast himself as the son, just as the poet sees himself as the father.[35] The father has grown wise through age and experience, and the lessons he subsequently teaches his son are Christian in tone and not only teach the young man how to lead a good Christian life, but also subtly construct a model of masculine behavior for the young man to emulate. The father ultimately teaches his son, and the poet his reader, how to be a “good” Christian man. These lessons are centred on obediance to God and the avoidance of sin; however, the two lessons relating to friendship and the control of one’s emotions and internal state are not only Christian, but deeply rooted in Anglo-Saxon culture and fundamental to the construction of masculinity.

One of the numerous lessons the father teaches his son is, “Do not let your chosen friend down, but always observe what is right and proper. Keep this rule strictly, that you should never be deceitful to your friend.”[36] This is an extremely important lesson for the son, as Anglo-Saxon society depended upon close-working relationships and friendships during times of both peace and war. Such relationships are idealized in heroic literature as the comitatus, a warrior group of men bound together by oath and under the governance of a lord. The heroic poem, The Battle of Maldon, composed after the defeat of the English army by the invading Viking army in 991, underlines the importance of loyal friendship because the outcomes of battles and survival depend upon loyalty. In accordance with the poem’s heroic style, the warriors are not blamed for the defeat at Maldon; rather, the poet creates a contrasting arena for those who found death in battle—obviously the loyal and the brave—and those who flee the battlefield.[37] According to the poet, the disloyalty of the deserters is the ultimate cause of the defeat, and the three noblemen who are deserters (Godric, Godwine and Godwig, sons of Odda) are treated with undisguised derision.

The men loyal to Byrhtnoth are the bricgweardas bitere fundon (furious guardians of the causeway [line 85]), and men wigheardne (hardy in war [line 75a]). They are the wigan unforhte . . . modige (brave undaunted warriors [lines 79b; 80b]) who stemnetton stiahicgende, / hysas æt hilde (stood firm / stubborn soldiers in battle [lines 122a-23a]). The poet further emphasizes the close relationships between Byrhtnoth and his men for not only does he alight down from his horse to be among his most loyal retainers (lines 23a-24b), he continuously encourages his men to set their minds on warfare (lines 127b-28a) and in response to the taunts of the Viking messenger, “he [Byrhtnoth] lifted his shield, shook his slim ash spear, held forth with his words and, angry and single- minded, gave him answer.”[38]

The language used to describe Byrhtnoth and his men is what Clare A. Lees calls the “language of masculinism.”[39] They are constructed within the masculine framework of the Germanic retainer found in Tacitus’ Germania: they are fierce, steadfast, courageous, single-minded and, most importantly, loyal. In contrast, the vocabulary used to describe the actions of the deserters, particularly Godric, emphasizes their ignominious characters and behaviors. Godric receives the full force of the poet’s condemnation for he not only flees from the battlefield, but he “deserted the good man who had often given him many a horse. He leapt upon that mount which belonged to his lord, into those trappings, as it was not proper for him to do.”[40] Godric’s treachery is heightened by the fact that he is presented in “the conventional literary character of the retainer, bound to his lord in allegiance in return for material gifts . . . In this case, ironically, the gift specified is many a horse.”[41] In accordance with the central metaphor of the poem, the representation of contemporary men and events as part of a heroic society,[42] Godric’s defection is the ultimate act of treachery for not only does he steal Byrhtnoth’s horse, he also beswicene (betrays, deceives) his companions.

Godric’s actions initiate a chain of events that encourages other men to desert the battlefield, for they mistake Godric on Byrhtnoth’s horse for Byrhtnoth himself. His boasts and promises of allegiance made before the battle are empty words, and as Offa perceptively observes, “that many there were speaking boldly who would be unwilling to suffer at time of need.”[43] Byrhtnoth’s retainers learn this lesson too late, and the death of Byrhtnoth and just before the impending death of the retainers, Offa reminds the reader that us Godric hæfa, / earh Oddan bearn, ealle beswicene (Godric, the cowardly son of Odda, has betrayed us [lines 237b-38]). That Offa is a loyal retainer and a ‘good’ man for his behavior is in accordance with not only the values that the heroic society extols, but also with those of Anglo-Saxon society in general. He is loyal to both his lord and kinsmen, and his promises are honored. Godric, on the other hand, is a liar, cheat and thief: he beswicene his comrades, and the disparity between what he says (his pledges of loyalty made before battle) and what he actually does (betray and abandon his kinsmen) signals to the reader that there is something decidedly wrong about Godric. The poet’s preoccupation with the importance of words and the internal state of the men underpins the poem’s construction of manhood; the single-minded and steadfast loyal retainers are ‘good’ men because they embody the masculine attributes required of a noble retainer. The deserters, however, have clearly allowed their desires to overwhelm their battle-resolve, and because of this uncontrolled and immoderate behavior, the poet subtly excludes them from the rational and steadfast framework of manhood constructed for the loyal warriors. Moreover, the mention of empty boasts and speeches by Offa after Godric and his brothers have deserted the battlefield underscores the importance of a man’s words, for they not only indicate to the world what sort of man he is, but also constitute a presentation of his body: they are the means by which he is recognized as a man.

Precepts similarly emphasizes the relationship between a man’s words and his body, for the young man must control his emotions and “avoid lies in the mouth…[and] always be wise in what you say, watchful against your desires; guard your words.”[44] On the surface level, the lesson here is that through education and guidance, a young man will abandon the impetuousness of youth, and develop the characteristics and manners required to lead a successful life. The poet’s preoccupation with words and the body, however, suggests that the young man should not just learn the external behaviors of the courageous and battle-hardy man, but he should also prepare his mind, because his internal state impacts upon his outward behavior and character. According to the poet, speaking constitutes a presentation of a man’s moral and spiritual character, and so he should not only control his bodily desires, but also be rational and moderate in mind for the two are intimately linked. As evidenced previously in the character of Godric, if the body and mind are not in accord, a man will be unable to control his desires and fears internally despite the outward display of strength and courage. A man’s words and actions must be in agreement. If they are not, and a man allows his desires to overcome his expected masculine reserve, then he becomes a danger, for if words and the body are intimately linked, then although his external appearance may be masculine, his lying words render his body as deceptive as the words he speaks.

Although Godric’s external appearance may be masculine, his inherently deceptive nature ‘undoes’ the reader’s initial recognition and identification of him as a man. It introduces an ambiguity because now his behavior has more in common with the feminine, particularly the wayward feminine seen in Maxims I and II. In stark contrast to the battle-eager and reticent man, a woman, presumably a noblewoman “belongs at her embroidery” (line 64b). There is no mention of education or guidance for women; rather, the woman belongs in the sedentary, all-female and private sphere: while men are ‘active’ in the public sphere, women are ‘passive’ and removed from the public world. The imagery of the private sphere, however, is shattered by the succeeding account of the widgongel wif (roving-woman): “A roving woman gives rise to talk— she is often accused of sordid things; men speak of her insultingly; and often her complexion will decay. A person nursing guilt must move about in darkness; the candid person belongs in the day.”[45] The “roving woman,” a woman displaying an excessive sexual appetite and open promiscuity, is a figure of spiritual and moral shame within the community and her behavior incurs condemnation and insult. She also invites gossip, and this gossip is heightened to accusations of “sordid things” and insults from men, the subtext being that she will never marry and procure the support of a husband. Furthermore, the “roving woman” is made repulsive by sin, as her exterior complexion reflects her internal moral corruption. Sexuality in a woman is treated as an ugly sin in Maxims I, and it is a punishable female, but not male, crime in the Anglo-Saxon law codes.[46] The “roving woman” must therefore use the cover of darkness to conceal her sinful actions and repulsive physical appearance.

Maxims II also links uncontrolled female sexuality with darkness and criminality: “The thief must go forth in murky weather. The monster must dwell in the fen, alone in his realm. The female, the woman, must visit her lover with secret cunning—if she has no wish to prosper among her people so that someone will purchase her with rings.”[47] The formulation of this maxim is rather peculiar, as what connection is the reader supposed to draw between the thief, the solitary monster and the woman meeting her lover? A thematic correlation between the thief and woman may be perceived by reference to Maxims I (lines 42a-46a), where a woman guilty of promiscuity must use darkness to hide her guilt. The “murky weather” and behaviors of both the thief and monster may be applied to that of the woman, who presumably meets her lover at night and whose actions, like those of the thief and monster,[48] are furtive and socially disruptive, for the woman steals out of her family home in the night to meet her lover in direct violation of prescribed social, cultural and gender roles.[49]

The distinct contrast between masculinity and femininity presented by Precepts and Maxims I and II underscores the entrenchment of long-standing characteristics associated with either the masculine and feminine in Anglo-Saxon culture. Despite the dichotomy of an active and rational masculinity on the one hand, and a passive and modest femininity on the other, it is evident that gender roles and ideals were transgressed, and there is subsequently a considerable overlap between the wayward masculine and feminine, as both are considered deceptive, inconstant, immoderate and uncontrolled. Both are regarded as weak, and the reader is implicitly expected to view the transgressors negatively. They are associated with the criminal (thieves) and monstrous because they similarly violate socio-cultural ideals. The reader is therefore confronted with behaviors and characteristics that will equip him or her with a model against which to compare their own behavior and that of others. They will subsequently be able to recognize transgressive behavior within the community, and construct a differential allowing them to exclude the offenders, for “if the schemes of recognition that are available to us are those that ‘undo’ the persons by conferring recognition, or ‘undo’ the persons by withholding recognition, then recognition becomes a site of power by which the human is differentially produced.”[50]

This processes of recognition and ‘undoing’ encountered previously in The Battle of Maldon and Maxims I and II, respectively, are also witnessed in the text-image relationships of the Wonders Donestre, and indeed in their very name. I propose that the author’s naming of the race functions to make them familiar—to name one’s enemy, so to speak[51]—and through the process of recognition, distances the Donestre from civilized society by exposing their monstrosity via their ability to speak human language, which they pervert. This perversion of human language to serve bodily appetites binds language with the corporeal, a bond that ultimately ‘undoes’ the Donestre, as well as the traveller. For speaking is ultimately a bodily act: “it is a vocalisation; it requires the larynx, the lungs, the lips, and the mouth. Whatever is said not only passes through the body but constitutes a certain presentation of the body . . . Saying is, one might say, another bodily deed.”[52] The Donestre’s use of language is wholly unnerving because firstly, the Donestre “know all human speech,” and this is a terrifying prospect as travellers from all nations are at risk: the danger posed by the Donestre is not limited but all encompassing. Secondly, the Donestre are consummate liars: although they are able to feign intimacy through language, every word they utter is a lie. The overarching theme of deception extends to the Donestre’s very bodies, which, through language, are rendered as deceptive as the words they speak. Although visually masculine, they are not necessarily male. Both the Vitellius and Tiberius images present the Donestre as excessive owing to their physical monstrosity: they are ‘more than male,’ but this heightened sense of masculinity—a hyper-masculinity—does not ring true despite the obvious male genitals displayed by both figures (Figures 1, 2). The Tiberius Donestre is an especially hyper-masculinized figure, but he is not a ‘good’ man. Moreover, he considerably blurs traditional masculine and feminine traits: he is extremely strong, aggressive, intelligent and rational, but also manipulative, beguiling, and driven by bodily desires. He is ‘more than male’ but at the same time ‘not quite male’ and ‘not quite female.’

The textual and visual identification of the Donestre’s maleness is thus destabilized by the blurring of traditional masculine and feminine attributes, a blurring that is compounded by their name, which appears to have the suffix, – estre, commonly used in Old English to demarcate feminine agent nouns, with a few exceptions.[53] This reading makes the assumption that the word-form, Donestre, is Old English; such a reading is not inconceivable as all three manuscripts state explicitly that “there is a race of people we call Donestre” (my italics). The “we” (OE: us) may be interpreted as a reference to Anglo-Saxon England, and the name itself—if it is indeed a creation of the Vitellius author or its exemplar—may have been formed specifically for the Anglo-Saxon reader. The race may not have been known by the name Donestre outside Anglo-Saxon England, but it is nevertheless a name, and as such should receive special attention, as there are several unnamed races in the manuscripts: one wonders why the author of the Vitellius manuscript (or its exemplar) named this particular race and not the two-faced people, for example? If treated as an Old English word-form, Donestre could be split into don- and -estre, respectively. The suffix resembles the feminine ending of an agent-noun, and the prefix could be interpreted as the Old English verb don (to do). When considered together, the translation of Donestre as “doer” does not make much sense. Granted, the Donestre occupies the active position in its interaction with the traveller: it is the “doer,” the speaker, beguiler, capturer, and devourer; but to fully appreciate the full meaning of don we must consider its wider usage in Old English. The Bosworth-Toller dictionary lists the possible translations of don as “to do, make, cause.”[54] Its wider meaning of “maker, causer” fits into the ‘active’ context of the Donestre’s domination and eventual devouring of the traveller. Moreover, the notion of performance attached to don is intriguing when considered in light of the framework of deception constructed by the presence of the lexical items leaslicum and beswicaa, respectively. It is therefore possible that the race is so named Donestre because they are indeed “doers, makers, causers, and performers.” That is, the name is not only descriptive of their behavior, but if the suffix is indeed feminine, the word, Donestre could be read as “female-doer,” a translation that reinforces their monstrously ambiguous identity, for although apparently male, they do as women do. They deceive and are more prone to behavior that defies socio-cultural masculine ideals given their uncontrolled temperaments and immoderate appetites.

To understand fully the author’s purpose for naming the race Donestre and endowing its members with soothsaying abilities, it is necessary to examine the vocabulary used to describe magical practitioners in the Anglo-Saxon period. A search of the Bosworth-Toller dictionary provides the following terms for soothsayers and soothsaying: wamm-freht (divination), deofol-witga (a devil- prophet, soothsayer, wizard), galdere (enchanter, charmer, sorcerer, soothsayer), halsere (soothsayer, diviner), wiglere (soothsayer) and wicca/wicce (wizard/witch, soothsayer, magician).[55] A negative perception of soothsayers may be discerned in the compounds wamm-freht and deofol-witga, respectively, as the first element of each compound has obvious negative connotations: wamm means, in the physical sense, “a blot, stain, spot.” It is also used in the wider context to indicate something foul and may be translated as “filth, impure, corruption; disgrace, moral stain, uncleanness, defilement.” The word deofol (devil) is identified with hell, damnation, and evil in Old English literature; for example, the Cædmon-poet uses it in his translation of the Book of Daniel to describe Nebuccaneezer’s deofol-witgan (dream-interpreters [line 3]).[56] Although the terms galdere and halsere refer to the use of charms, an important feature of Anglo-Saxon medicine,[57] Ælfric’s homilies contain numerous prohibitions against “magical charms, or any kind of witchcraft,”[58] and he warns that “no man shall enchant a herb with magic.”[59]

Wulfstan’s Sermo Lupi ad Anglos (The Sermon of the Wolf to the English) is similarly critical of witches and includes them in a lengthy list of sinners: “and here there are harlots and infanticides and many foul adulterers, and here there are witches and sorceresses.”[60] Dorothy Whitelock has suggested that Wulfstan’s use of ælcyrian (ON: valkyrja [valkrie]) presumably refers to some kind of witch, although it glosses classical names (the Furies, a Gorgon, Bellona, and Venus, respectively) in the eighth-century Corpus Glossary, and could equally refer to a supernatural being.[61] The phrase, wiccan 7 ælcyrian, is not recorded elsewhere. In this context, it is reasonable to assume that it does indeed refer to a female witch of some form; it is also possible that Wulfstan deliberately employed a term laden with “pagan” associations to emphasize that the practice of magic— irrespective of its application—is a damnable and unchristian offense. Although magical practitioners were not necessarily regarded as evil by Anglo-Saxon society, it is clear that a tension existed between religious authorities and traditional folk-practices. The religious writers and secular authorities of the period strove to eradicate traditional practices considered remnants of a former “pagan” culture after the introduction and acceptance of Christianity. The secular laws of Edward and Guthrum includes the following stern warning that:

If wizards or sorcerers, perjurers or they who secretly compass death, or vile, polluted, notorious prostitutes be met with anywhere in the country, they shall be driven from the land and the nation shall be purified; otherwise they shall be utterly destroyed in the land – unless they cease from their wickedness and make amends to the utmost of their ability.[62]

The appearance of wiccan (wizards) and wigleras (sorcerers) amongst murderers, thieves and prostitutes—the lowest criminal spectrum of Anglo-Saxon society—underscores the marginal position of magical practitioners within the community. This stratum of undesirables poses a direct threat to the moral and spiritual condition of the body social: they lie, cheat, steal, and murder, thereby serving unchristian and unnatural agendas and appetites. Further, magical practitioners defy Christian social norms and customs, and are therefore not only morally suspect but also equated with the criminal and exiled.

Although both Wulfstan and the law code include male magical practitioners in their lists (wiccan and wigleras, respectively), the inclusion of myltestran (prostitute, whore), horcwenan (whore, prostitute), and bearnmyraran (child-murderers) before ælcyrian (witch) suggests that writers associated criminal magical abilities more with the female than the male, given that these are all female crimes: although horingas (adulterer)[63] appears to be the exception, it is also a punishable female crime. The linking of myltestran with bearnmyraan, and ultimately ælcyrian, underscores the transgressive nature of female magical practitioners, for both the law code and Wulfstan’s homily emphasize not that the “harlots” are professional prostitutes, but that they practice murder and abortion, possibly committed by magical means, in order to cover up their or others’ adulterous and licentious behavior.[64] They therefore defy acceptable gender and sexual ideologies, for not only do they commit sexual crimes, their behavior goes unnoticed and unpunished because they are able to conceal their true natures though deception and magic. Their actions are therefore contrary to both ‘natural’ and social law. Although both Wulfstan’s homily and Edward and Guthrum’s law code are “responses prompted by [the] association of sexual laxity with Viking paganism, and the influence [they] thought this was having on the country as a whole,”[65] they nevertheless reflect social attitudes towards women made suspect either through their transgressions or by stereotyped behaviors associated with particular female professions and abilities.

In light of these complex contemporary social and linguistic considerations, it is now possible to comprehend the full implications and monstrosity of the Donestre’s appearance and soothsaying abilities. The Donestre are horror-inspiring because although they are located at the margins of the known world, they appear to have a position in society, comparable to the status of magical practitioners in Anglo-Saxon society. Their traits are recognisable and easily identifiable within the community, but they are figures to be feared and regarded with suspicion because of their dangerous abilities. They affect the transition from ‘out there’ to ‘right here,’ and are therefore extremely dangerous because, though human on some level, this semblance of humanity ironically underscores a weakness, similar to that of the deserter Godric, which, when recognized, destabilizes and excludes the Donestre from civilized society. His performance of human language is his ‘undoing,’ as speech is the means by which he satisfies his desire for human flesh, and exposes his monstrosity not only to the reader-viewer, but also to himself. The final weeping scene might be read (as in Cohen’s argument) as demonstrative of the Donestre’s self-recognition as an abomination, an individual whose personhood has been reduced to the level of a bestial monster. Their less-than-human status is further conveyed by the denial of recognisable and stable sexual and gender identities. Though part human, the Donestre’s monstrous behavior renders them ‘not human’ at the same time, and, consequently, their gender and sexual identities are made ambiguous, because uncontrolled appetites and weeping were not seen as masculine traits; neither were deceiving nor betraying one’s acquaintance. Moreover, the Donestre’s soothsaying abilities and agent-noun name link them with the fornicators, adulterers, murderers, thieves, infanticides, and, ultimately, magical practitioners—with those who, like the Donestre, disguise their internal moral and spiritual blackness from the community in order to commit crimes against that self-same community, and humanity as a whole.

References

| ↑1 | Judith Butler, Undoing Gender (New York: Routledge, 2004), 2. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203499627 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Ibid., 1. |

| ↑3 | Ibid., 2. |

| ↑4 | De civitate dei, Book 14. See Augustine of Hippo, The City of God Against the Pagans, ed. and trans. R. W. Dyson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 581-88. |

| ↑5 | London, British Library, MS Cotton Vitellius A.xv, fols. 78v-87v; London, British Library, Cotton Tiberius MS B.v, fols. 98v-106v; Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Bodley 614, fols. 36r-48r. On the Vitellius manuscript, see also the articles by Asa Simon Mittman and Susan M. Kim in this volume. |

| ↑6 | On the dating of the manuscripts, see Andy Orchard, Pride and Prodigies: Studies in the Monsters of the Beowulf-Manuscript (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1995), 2, 20, 21-22. |

| ↑7 | The contents of all three manuscripts are listed in M. R. James, Marvels of the East (Oxford: Roxburgh Club, 1929), 1-8. See also Mary B. Campbell, The Witness and the Other World: Exotic European Travel Writing, 400-1600 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1988), 62. |

| ↑8 | Orchard, Pride and Prodigies, 86. |

| ↑9 | Liber monstrorum 1.40: “Est gens aliqua commixtae naturae in Rubri maris insula quam linguis omnium nationum loqui posse testantur. Et ideo homines de longinquo uenientes, eorum cognitas nominando, adtonitos faciunt, ut decipiant et crudos deuorent” (ed. and trans. Orchard, Pride and Prodigies, 280-1). All quotations and translations of the Liber monstrorum are from Andy Orchard’s edition and translation. |

| ↑10 | Ann Knock has suggested the author’s “concern to keep the original Latin accessible to his readers through the retention of significant names is consistent with the conclusion that he saw this text as of scientific or even taxonomic interest.” See Ann Knock, “Analysis of a Translator: the Old English Wonders of the East,” in Alfred the Wise: Studies in Honour of Janet Bately on the Occasion of her Sixty- fifth Birthday, ed. Jane Roberts and Janet Nelson, and Malcolm Godden (Woodbridge: D. S. Brewer, 1997), 121-26 (at 124). |

| ↑11 | See Book 11 (“The Human Being and Portents”) in The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville, trans. Stephen A. Barney, W. J. Lewis, J. A. Beach, and Oliver Berghof (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 231-46. |

| ↑12 | “Donne is sum ealand on oære Readan Sæ, pær is moncynn pæt is mid us Donestre genemned, pa syndon geweaxene swa frihteras fram oan heafde oo oone nafelan, 7 se ooer dæl byo mannes lice gelic. 7 hi cunnon eall mennisc gereord. I>onne hi fremdes kynnes mann geseoo, oonne næmnao hi hine 7 his magas cuora manna naman, 7 mid leaslicum wordum hine beswicao, 7 him onfoo, 7 pænne æfter pan hi hine fretao ealne butan his heafde 7 ponne sittao 7 wepao ofer oam heafde,” Marvels of the East 20 (ed. and trans. Orchard, Pride and Prodigies, 196-97). All quotations and translations of the Wonders of the East are from Andy Orchard’s translation and edition, |

| ↑13 | Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, Of Giants: Sex, Monsters, and the Middle Ages (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1992), 2. |

| ↑14 | Ibid. |

| ↑15 | Ibid. |

| ↑16 | Nicholas Howe, Writing the Map of Anglo-Saxon England: Essays in Cultural Geography (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 172-73. |

| ↑17 | “Itaque insula est in Rubro Mari in qua hominum genus est quod apud nos appellatur Donestre, quasi divini a capite usque ad umbillicum, quasi homines reliquo corpore similtudine humana, nationum omnium linguis loquentes; cum alieni generis hominem uiderint, ipsius lingua appellabunt eum et parentum eius et cognatorum nomina, blandientes sermone ut decipiant eos et perdant; cumque comprehenderint eos, perdunt eos et comedunt, et postea conprehendunt caput ipsius hominis quem comederunt et super ipsum plorant,” Marvels of the East 20 (Orchard, Pride and Prodigies, 178-79). |

| ↑18 | Tom Tyler, “Deviants, Donestre, and Debauchees: Here be Monsters,” Culture, Theory & Critique 49 (2008): 113-31 (at 118). https://doi.org/10.1080/14735780802426700 |

| ↑19 | Tyler, “Deviants,” 118-20. |

| ↑20 | Ibid., 120. |

| ↑21 | Geoffrey Galt Harpham, On the Grotesque: Strategies of Contradiction in Art and Literature (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982), 5-9. |

| ↑22 | Mary C. Olson, Fair and Varied Forms: Visual Textuality in Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts (New York: Routledge, 2003), 150. |

| ↑23 | Ibid. |

| ↑24 | John Block Friedman, The Monstrous Races in Medieval Art and Thought (1981; repr., New York: Syracuse University Press, 2000), 32. |

| ↑25 | Paul Freedman, “The Medieval Other: the Middle Ages as Other,” in Marvels, Monsters, and Miracles: Studies in the Medieval and Early Modern Imaginations, ed. T. S. Jones and D. A. Sprunger (Michigan: Western Michigan University, 2002), 1-24 (at 3). |

| ↑26 | Ibid., 10. |

| ↑27 | Asa Simon Mittman and Susan M. Kim, “The Exposed Body and the Gendered Blemmye: Reading the Wonders of the East,” in Sexuality in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Times: New Approaches to a Fundamental Cultural-Historical and Literary-Anthropological Theme, ed. Albrecht Classen (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2008), 117-216 (at 174). https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110209402.171 |

| ↑28 | Susan M. Kim, “The Donestre and the Person of Both Sexes,” in Naked Before God: Uncovering the Body in Anglo-Saxon England, ed. B. C. Withers and J. Wilcox (Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 2003), 163. |

| ↑29 | Olson (Fair and Varied Forms, 141) transcribes the word as fri[h]teras. Andy Orchard (Pride and Prodigies, 196) and Paul Allen Gibb (“Wonders of the East: A Critical Edition and Commentary,” [Ph.D. diss., Duke University, 1977], 93, n. 20:20) transcribe it as frifteras. |

| ↑30 | A. Knutson, The Gender of Words Denoting Living Beings in English and the Different Ways of Expressing Difference in Sex (Ph.D. diss., Lund, 1905), 21-22. See also Charles Jones, Grammatical Gender in English: 950 to 1250 (London: Croom Helm Ltd., 1988); Dieter Kastovsky, “Deverbal Nouns in Old and Modern English: from Stem-formation to Word-formation,” in Trends in Linguistics: Studies and Monographs 29, ed. Jacek Fisiak (Berlin: Mouton Publishers, 1985), 221-262; and Bruce Mitchell, Old English Syntax, Vol. I and II (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985). https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110850178.221 |

| ↑31 | Kim, “Donestre,” 164. |

| ↑32 | Butler, Undoing Gender, 20. |

| ↑33 | Joan Cadden, Meanings of Sex Difference in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 105-6. See also Miri Rubin, “The Person in the Form: Medieval Challenges to Bodily Order,” in Framing Medieval Bodies, ed. Sarah Kay and Miri Rubin (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1994), 100-122; and Danielle Jacquart and Claude Thomasset, Sexuality and Medicine in the Middle Ages, trans. Matthew Adamson (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985). |

| ↑34 | Sara Mendelson and Patricia Crawford, Women in Early Modern England 1550-1720 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998), 18. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198201243.001.0001 |

| ↑35 | T. A. Shippey, Poems of Wisdom and Learning in Old English (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 1976), 2. |

| ↑36 | Precepts, lines 23a-26b: “Ne gewuna wyrsan, widan feore, / ængum eahta, ac pu pe anne genim / to gesprecan symle spella ond lara / rædhycgende, sy ymb rice swa hit mæge” (ed. and trans. Shippey, Poems of Wisdom and Learning, 48-9). |

| ↑37 | The Battle of Maldon, ed. D. G. Scragg (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1981). |

| ↑38 | The Battle of Maldon, lines 42b-44b: “bord hafenode, / wand wacne æsc, wordum mælde, / yrre and anræd ageaf him andsware.” All Battle of Maldon quotations are taken from Scragg’s edition, and translations are from Anglo-Saxon Poetry, trans. and ed. S. A. G. Bradley (London: Everyman, 1995). |

| ↑39 | Clare A. Lees, “Men and Beowulf’,” in Medieval Masculinities: Regarding Men in the Middle Ages, ed. Clare A. Lees (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994), 129-48 (at 142-43). |

| ↑40 | The Battle of Maldon, lines 187a-190b: “Godric fram gupe, and pone godan forlet / pe him mænigne oft mear gesealde; / he gehleop pone eoh pe ahtehis hlaford, / on pam gerædum pe hit riht ne wæs.” |

| ↑41 | Scragg, Battle of Maldon, 22. |

| ↑42 | Ibid., 27. |

| ↑43 | Battle of Maldon, lines 200a-1b: “pæt pær modlice manega spræcon / pe eft æt pær[f]e polian noldon.” |

| ↑44 | Precepts, lines 35b; 41b-42b: “mupe lyge . . .Wes pu a giedda wis, / wær wio willan, worda hyrde.” |

| ↑45 | Maxims I, lines 65a-68b: “widgongal wif word gespringeo / oft hy mon wommum biliho; / hæleo hy hospe mænao, oft hyre hleor abreopeo. / Sceomiande man sceal in sceade hweorfan, scir in leohte geriseo.” All quotations from Maxims I and II are taken from Shippey’s edition; all translations are from Bradley’s edition. |

| ↑46 | See F. L. Attenborough, The Laws of the Earliest English Kings (1922; repr., Clark, NJ: The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd., 2006). |

| ↑47 | Maxims II, lines 42a-46a: “JJeof sceal pystrum wederum. / JJyrs sceal on fenne gewunian, / ana innan lande. Ides sceal dyrne cræfte, / fæmne hire freond gesecean, gif heo nelle on folce gepeon / pæt hi man beagum gebicge.” |

| ↑48 | The monsters Grendel and his mother in Beowulf share similarities with the monster of Maxims II. Grendel is mære mearc-stapa, se pe moras heold, / fen ond fæsten (a notorious prowler of the marches, who patrolled moors, swamp and impassable wasteland [lines 103a-104a]). He is deorc deap-scua (a dark death shadow [line 160a]). His segregation from the company at Heorot is made explicit by the fact that he cannot abide the sounds of merriment coming from the hall. He stalks up Heorot in the night and the carnage is discovered on uhtan mid ær-dæge (the half-gloom just before daybreak [line 126]). After Grendel’s death, his mother takes vengeance for her son’s death; however she is an ides, aglæc-wif (a lady, a monster of a woman [line 1259a]) and her persecution of Heorot is contrary to the heroic code as feuds should be settled by men, not women. The figures of Grendel and Grendel’s mother are monstrous in comparison with the company at Heorot, as their acts of abandoned violence, aggression and duplicity are contrary to the heroic code. In addition, they both share common features with the monster in Maxims II as Grendel and his mother are solitary figures that dwell in a wasteland fen situated at the fringes of the civilized world. Although nothing more than the monster’s solitary existence is mentioned in Maxims II, when it is considered in light of the monsters in Beowulf, Anglo-Saxon monsters are in general solitary, socially disruptive, and associated with darkness and thievery. All quotations from Beowulf are taken from George Jack, Beowulf: a Student Edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994). Translations are from Edwin Morgan, Beowulf: a Verse Translation into Modern English (Manchester: Carcanet, 2002). |

| ↑49 | Paul Cavill, Maxims in Old English Poetry (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1999), 180. |

| ↑50 | Butler, Undoing Gender, 2. Butler also contends that sex is a “regulatory ideal” which materializes through “a forcible reiteration of those norms. That this reiteration is necessary is a sign that materialisation is never quite complete, that bodies never quite comply with the norms by which their materialisation is impelled.” See Judith Butler, Bodies that Matter: on the Discursive Limits of “Sex” (New York: Routledge, 1993), 2. |

| ↑51 | Foucault observes that giving a name is “a form of power which makes individuals subjects…subject to someone else by control and dependence.” Michel Foucault, “The Subject and Power,” Art After Modernism: Rethinking Representation, ed. Brian Wallis (New York: New Museum of Contemporary Art, 1984), 420. |

| ↑52 | Butler, Undoing Gender, 172. See also See Jean LeClerq’s seminal discussion of ruminatio as a chewing of words in The Love of Learning and the Desire for God: A Study of Monastic Culture, trans. Catharine Misrahi (New York: Fordham University Press, 1974), 71-88. |

| ↑53 | Knutson observes that some of the forms ending in –estre were applied to male beings; for example, bæcestre (m. baker). However, classical West Saxon also used the morphological contrast bæcere/bæcestre to denote male/female roles, with –estre signalling the feminine correspondent of masculine nouns ending in –ere. For a more detailed discussion, see Knutson, Gender of Words, 21; and Jones, Grammatical Gender in English, 6. |

| ↑54 | See s.v. “don” in Bosworth-Toller Dictionary, available online via the German Lexicon Project: http://lexicon.ff.cuni.cz/html/oe_bosworthtoller/b0208.html (accessed 13 December 2009). |

| ↑55 | Thomas Northcote Toller, An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary: Based on the Manuscript Collections of the Late Joseph Bosworth (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1921-1979). |

| ↑56 | Benjamin Thorpe, Cædmon’s Metrical Paraphrase of Parts of Holy Scriptures, in Anglo-Saxon: with an English Translation, and a Verbal Index (London: The Society of Antiquaries, 1832), 223. |

| ↑57 | Bill Griffiths, Aspects of Anglo-Saxon Magic (Hockwold-cum-Wilton: Anglo-Saxon Books, 1996), 89. |

| ↑58 | wyrigedum galdrum, oppe æt ænigum wiccecræfte.” See Benjamin Thorpe, The Homilies of Ælfric (London, 1844-6), 474-75. |

| ↑59 | “ne sceal nan man mid galdre wyrte besingan.” See Thorpe, Homilies of Ælfric, 476-77. |

| ↑60 | “7 her syndan myltestran 7 bearnmyroran 7 fule forleene horinas manee, & her syndan iccan & ælcyrian” (ed. Dorothy Whitelock, Sermo Lupi ad Anglos [Exeter: Exeter University Press, 1989, 64]; trans. Toller, Anglo-Saxon Dictionary, 1213). See also Melissa Bernstein Ser, The Electronic Sermo Lupi ad Anglos: http://english3.fsu.edu/~wulfstan/noframes.html (accessed 3 February 2010). |

| ↑61 | See Whitelock, Sermo Lupi, 64-65, nn. 169 (bearnmyroran), 170 (wiccan), and 171 (wælcyrian). |

| ↑62 | “Gif wiccan ooo wigleras, mansworan ooo morowyrhtan oooe fule, 7 afylede, æbere horcwenan ahwar on lande wuroan agytene, oonne fyse hi man of eared 7 clænsie pa oeode, oooe on earde forfare hy mid ealle, buton hig geswican 7 pe deoppor gebetan” (ed. and trans. Attenborough, Laws of the Earliest English Kings, 108-9). |

| ↑63 | All translations from Loring Holmes Dodd, A Glossary of Wulfstan’s Homilies (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1908). |

| ↑64 | For a discussion of the Old English lexis for “prostitute,” see Julie Coleman, “Lexicology and Medieval Prostitution,” in Lexis and Texts in Early English: Studies Presented to Jane Roberts, ed. Christian J. Kay and Louise M. Sylvester (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2001), 69-87. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004487024_011 |

| ↑65 | Christine Fell, Cecily Clark, and Elizabeth Williams, Women in Anglo-Saxon England (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985), 66. |