Fran Altvater • University of Hartford

Recommended citation: Fran Altvater, “Barren Mother, Dutiful Wife, Church Triumphant: Representations of Hannah in I Kings Illuminations,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 3 (2011). https://doi.org/10.61302/VBVV1009.

The Hannah story (I Kings 1:1-17/I Samuel 1:1-17) is written within the social context of marriage around 1100 B.C.E.: the complications of the contractual marital obligations, the expectations of procreation, and the politics of remarriage and co-marriage, particularly around the production of heirs.* In this essay, I am focusing on the nature of Hannah’s prayer in the text and in medieval illumination. Prayer is critical as the human communication with the divine and Hannah’s prayer draws attention as a singular example of a woman at prayer, subsequently upheld in Jewish traditions even as the paragon of prayer[1] Because she is both submissive and transgressive, Hannah is both role model and anti-role-model; the Biblical type-scene of the barren woman granted a miraculous child was a common narrative technique used to reinforce cultural stereotypes and accentuate the positive while clarifying the negative. Over the course of the Middle Ages, the image of Hannah becomes a type-scene for medieval illuminators and readers. These compositions use model forms which gloss the characters as Christ, Church and Synagogue to create monastic models, radical abstractions of prayer, and constructions of marriage. The image of Hannah becomes the image of the Church and a paragon of a good wife.

I am a modern woman—I read the text of I Samuel looking for a strong heroine. I want a woman who knows her heart and the odds against her but tries anyway, bucking the system to make God hear her and change her life. The text can certainly reward that reading. But the text can also reward the reading that despite having broken strongly imbedded social norms, Hannah is forgiven for her actions and her petition is granted because it suits God’s purpose. The text is rich because it supports both social transgression and normativity. Precisely because I read the text as a modern woman, what becomes jarring is the degree to which the medieval images are part of the containment of Hannah. The images show me the normative, making it harder to see the value of being a woman who crosses boundaries. As a modern woman, I read the images to make them stand against their own gloss; I read these images to reclaim authority for my interpretation of the text.

Per Visibilia Invisibilia Demonstrare [2]

There are two issues of visualization in the discussion of these images from I Kings. These images of Hannah force us to revisit the relationship between text and image and the complications of producers and audiences. Indeed, the divergence from the standard narrative has been the focus of scholarship; C.M. Kauffmann identified the Bury Bible’s anomalous presentation of clothing rather than food as portions from Elkanah because of its reliance on a relatively obscure commentary by the ninth-century Pseudo-Jerome Quaestiones in Libros Regum.[3] Undeniably, there is a degree to which images illustrate their accompanying words, paralleling the words of the narrative as a tangible visual object. And yet there is also undeniably an impulse to use the image to expand the text, to offer a visual gloss to hone, direct, or change the themes underlying the narrative. As Herbert Kessler has theorized, “…various aspects of sophisticated works of medieval art—subject matter, form, and material—were devised to engage the viewer in an anagogical process, offering spiritual readings of texts, elevating established categories of objects and iconographies, and deploying materials in such a way that physical presence is simultaneously asserted and subverted.”(Herbert Kessler, Spiritual Seeing: Picturing God’s Invisibility in Medieval Art (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000), xv. ))As medievalists, we tend to think of “anagogical process” from its specifically Christian perspective, leading the all-too-mortal-human to the understanding of her spiritual soul through Christ; if we turn back, however, to its more general definition: “deriving from, pertaining to, or reflecting the moral or idealistic striving of the unconscious”[4],the subtlety of anagogy as a social ideological process comes back to us. These medieval images of Hannah from the I Kings opening reveal precisely this anagogical slippage of their periods and audiences. An Old Testament story, it visually prefigures Christian theology of Church supplanting Synagogue. When Hannah prays, the images reveal the socially gendered, idealized constructions of public prayer. When Elkanah enters the picture, these images affirm the moral figuration of marriage in medieval culture.

This idea of visibility and visualization is also critical in our thinking as feminists. It isn’t that Hannah’s desire for a child is transgressive; in itself, motherhood is a gendered normative role for women. Social definition of “woman” in the text is that she is only successful in her gendered role if she is both wife and mother: “Motherhood is indeed extolled in the Hebrew Bible, but it is extolled to the extent that it validates the father’s authority and consolidates the son’s right to security and prosperity…her validation functions ultimately as the validation of the patriarchal hierarchy.”[5] The crux of the Hannah text is precisely how visible her prayer is. Hannah moves deliberately to the realm of visibility in order to claim for herself the socially defined role of mother that she has been denied because the Lord has closed her womb; she acts unwomanly— breaking the bounds of propriety so thoroughly that Eli assumes that she must be drunken, chemically altering her very sense of the world—in order to be womanly. The images, however, gloss visibility and prayer to re-visualize Hannah as a woman. Substitutions are fluid—Hannah is seldom allowed to be her own textual self. In examining these images, we first reclaim Hannah‟s visibility as a character who speaks her own pain of infertility. We also acknowledge the very real medieval tendencies to prescribe social definition in order to exclude the non-normative, whether in gender, sexuality, race, or creed. Finally, we return the fullness of Hannah as an individual from the common medieval effacing which fuses her to a type, a personification, in order to serve a larger institutional identity.

Text and Context of Hannah’s Prayer

From the Biblical text, we know Elkanah had two wives, Hannah, who had no children, and Peninnah, who did. As a testament to his religious faith, every year Elkanah journeys from his city to Shiloh to sacrifice at the altar. Elkanah gave offering portions to all of the members of his family. To Hannah he gives only one portion because “the Lord had closed her womb” (1 Samuel 1:5). For years, Peninnah provoked Hannah for her childlessness. Hannah wept and would not eat, despite her husband’s pleas: “Hannah, why do you weep? And why do you not eat? And why is your heart sad? Am I not more to you than ten sons?” (1 Samuel 1:8). Hannah leaves the company and goes into the temple, the text specifying that she passed Eli seated at the doorpost of the temple; “She was deeply distressed and prayed to the Lord, and wept bitterly.” (1 Samuel 1:10). Hannah then vows that if God remembers her, she will dedicate the son as a Nazarite to God. We are told that Eli observes her, “Hannah was speaking in her heart; only her lips moved, and her voice was not heard; therefore Eli took her to be a drunken woman. And Eli said to her, “How long will you be drunken? Put away your wine from you.” But Hannah answered, “No, my lord, I am a woman sorely troubled; I have drunk neither wine nor strong drink, but I have been pouring out my soul before the Lord. Do not regard your maidservant as a base woman, for all along I have been speaking out of my great anxiety and vexation.” Then Eli answered, “Go in peace, and the God of Israel grant your petition which you have made to him.” (1 Samuel 13-17)

In the Biblical and mishnaic contexts (up to ca. 600 C.E.), women’s prayers were excluded from the time-binding of men‟s liturgy and therefore generally excluded from halakhot on masculine, public prayer. “The exclusion of women from praying in a social context, that is, not in a synagogue; and the spontaneous quality of their prayers, highlight the anti-establishment, or individualistic aspect of their prayers”.[6] This characterization, clearly meant to redeem the anti-institutional standing of women’s prayer in Jewish tradition and minimize the degree to which it seems valued less than men’s, describes a larger pattern essentializing women’s prayer as emotional. From early on, Jewish reworkings of the Hannah story such as in the Liber Antiquitatem Biblicarum, also known as Pseudo-Philo and written in the period between 135 BCE and 70 CE, rewrite the language of Hannah’s prayer to reinforce the importance of prayer after the destruction of the Second Temple and to contain its socially transgressive nature as silent and pious.[7]

For Christian medieval women, prayer is complicated by the profound effects of class on both lay and monastic participation, the very different public-sanctioned arenas of women’s monasticism, and the later derivation of elements like the Book of Hours to draw together women’s lay and monastic customs. The societal construction of women as subordinate and sinful and the institutional exclusion from liturgical office certainly diminished women’s roles in public lay spheres of prayer. Numerous eleventh and twelfth century reformers—Odo of Cluny, Cardinal Humbert, Idung of Prufening— suggest that it is women‟s virtue to be silent and unseen, “permitted neither to speak in church nor rule over men”.[8]

In both Jewish and Christian traditions, it is how Hannah prays that is objectionable: moving from the acceptable private sphere for women’s prayer to the public male-gendered and male-centered religious setting of the Shiloh temple; in doing so, she has usurped power beyond her status as a woman. Hannah‟s prayer is disruptive; it does not fit the social expectations for women‟s prayer, being neither silent nor private. Given its social dangerousness, the institutional pressure is to rewrite and revisualize and reinterpret the narrative so that it can be taken for its merits, not its contraventions.

Not a Woman but an Institution

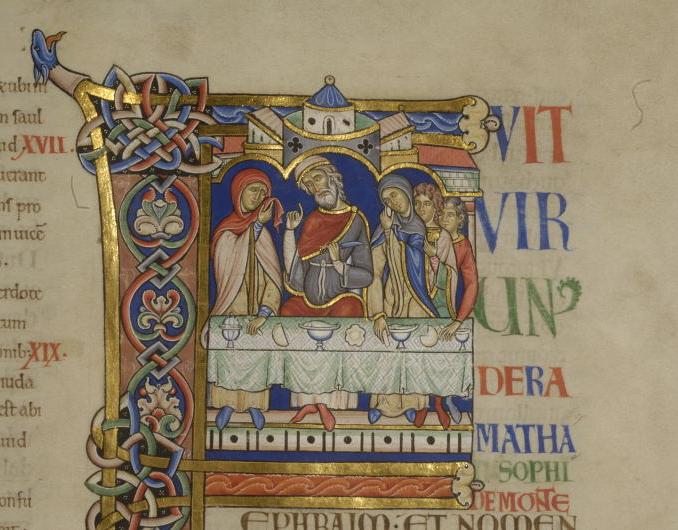

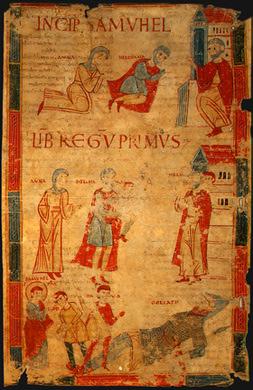

A number of Romanesque so-called “Giant Bibles”, results of the eleventh-century Touronian reforms, adopted the Hannah story as the opening of the Book of Kings.[9] Typical of these is the Winchester Bible, 1160-1175 (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Initial from I Kings. Winchester Bible, fol. 88. (Winchester Cathedral Library)

Narratively, the table sets our context at the division of portions but it is far more complicated a gloss. Socially, it sets Hannah in her properly domestic sphere. Visually, the laden table translates Hannah to the specific iconographic landscape of the Last Supper and Last Judgment. Elkanah’s body language closes out Peninnah on his left as much as it favors Hannah on his right: he faces away from her; the knife in his hand points back to Peninnah.[10] Deliberate references were designed by a literate illuminator for an erudite audience: they rest on Jewish interpretations of Hannah as Wisdom and illustrate not just the story but the well-known commentary on the Book of Kings of Gregory the Great and its widely-disseminated version in the Glossa Ordinaria. Elkanah, described as “vir unus” in the text, is glossed as Christ; citing Augustine, Gregory notes that Hannah, who receives her portion in sorrow, becomes the Church, receiving the glory of Christianity in the sorrow of the Passion.[11] Gregory holds that it makes sense that Peninnah is mentioned secondly because as Synagogue, she is second in dignity to the Church.[12] “Peninnah is the Synagogue, the Law once fecund, but now stands made barren for her infidelity. The sterile Hannah, blessed with progeny, stands for the era of grace inaugurated by the coming of the Redeemer.”[13]

In the descender of the “F” (Figure 2), we see Hannah, scroll in hand, looking up to the hand of God in the upper left. For all the emphasis on the historiation of portions and family situations in the upper space, where did the story go? Where is Eli? Where is Hannah’s embarrassing desperation in public prayer? Where is the miracle baby Samuel? We skip the unseemly narrative and go straight for pious decorum. This is the scene of Hannah’s second prayer—not the prayer for the child but the thanksgiving for his receipt—a prayer “so universal and so particular” that it has been integrated into the primary liturgy of Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year.[14] Her speech is the written scroll with the words of her canticle of praise, familiar to the monastic audience from the Lauds Office in the Roman Breviary. Despite her gender,[15] Hannah praises God as the monks praise God. The personal devotion of Hannah is co-opted as the prayer of the Church to set the tone for the monastic audience.

Fig. 2. Initial from I Kings. Winchester Bible, fol. 88. (Winchester Cathedral Library)

The Winchester Bible initial just discussed is typical of twelfth century English monastic production; the Winchester Bible is also a lavish example followed by a page of illuminations (Figure 3),now separated from the Bible in the collections of the Morgan Library.[16] This page is one of four full illuminated pages in the Bible which suggests the narrative scenes were meant to be read in conjunction with the initial opening the Book of Kings. But even here the narrative emphasis is not Hannah’s own. The page begins the narrative of Samuel’s miraculous birth at the lower left with two separate bays showing Hannah’s prayer. In prayer on the left, Hannah kneels alone. This illuminator rejects the naturalism of showing her mouth open perhaps to show the properly expected silence? As scholar Lillian B. Klein has noted, “Mere ‘mouthing’ seems insufficient evidence for the unquestioned judgment Eli makes”[17]. In the second bay, the artist then conveys the directness of Eli’s looming pointing confrontation with the circular wholeness of Hannah’s responsive gesture. The division simultaneously respects the story, its social premises, and the integrity of Hannah’s faith. But as the rest of the page shows, Hannah is not here to set her own story she is meant to set the context of Samuel as God‟s own even before his birth. The emphasis is on Samuel’s sanctity as created by God, called by God, serving God. Samuel’s story, like the subtext of the initial it reinforces, is the monks’ own story.

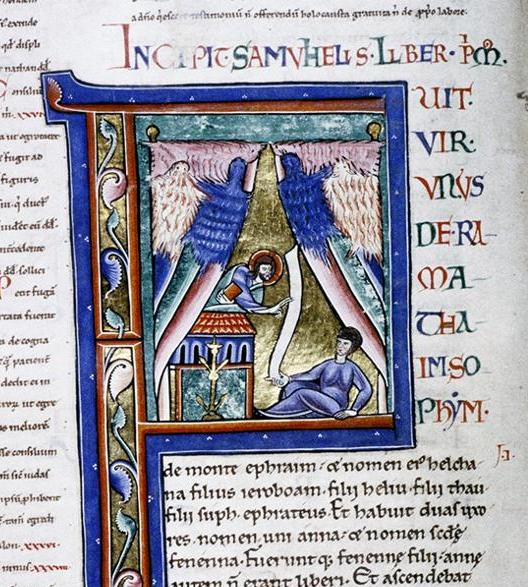

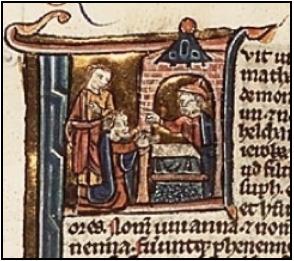

Fig. 4. Giffard Bible, ca. 1165 (The Bodleian, University of Oxford MS Laud 752 99v)

These themes of monastic resonance were clearly current, even in an exceptional image such as initial of the Book of Kings in the mid to later 12th century Giffard Bible (Figure 4). Even among historiated initials of the Book of Kings, this initial stands out—the tents of the temple enclose a structure partly altar, partly architectural church, from which Christ/Logos pops up. Hannah’s prayer springs directly from her hand as she reclines before the Logos. Augustine cannot see Hannah as separate from the church: “This Hannah prophesied, Holy Samuel’s mother, in whom the change of the ancient priesthood was prefigured and now fulfilled, when the woman with many sons (synagoga) was made feeble so that the barren that brought forth seven (ecclesia) might receive the new priesthood in Christ.”[18] For the specific audience of the Giffard Bible, which Jennifer Sheppard has noted was an erudite monastic audience markedly interested in the establishment of the Church, Hannah is significant only in the ways which she prophesies the New Covenant; like the obvious textual links between her prayer of praise and the Magnificat of Luke 1: 46-55, the visual links to the Virgin Mary in color, blooming candlestick, and Nativity pose help stress the connections. The twelfth-century erudite monastic audiences solve the problem in chains of theological analogy, substituting one woman (Hannah) for another (Mary) for another (Wisdom) for another (the Church).

Not a Woman but an Action

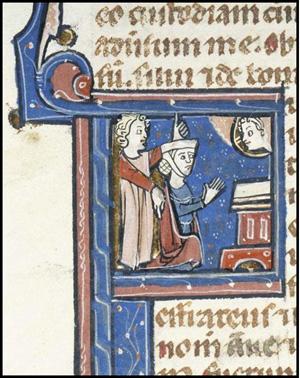

One way to neutralize Hannah’s exceptionality is to focus on the singular aspect that makes her exceptional: her prayer. We see developing a type-scene that focuses the viewer on the issue of prayer, carefully including the presence of Eli to emphasize Hannah‟s proper social containment (Figure 5 and Figure 6). Not coincidentally, all of these initials are in smaller scale later thirteenth century bibles,[19] reflecting the well documented shifts from monastic to a wider lay audience‟s personal use.[20] We can imagine a lay audience both male and female responding to a depiction which emphasizes personal prayer and its rewards.[21] The visual glosses make Hannah the epitome of institutional prayer and the virtues of the contemplative life. In these images, we see the construction of a mode of legitimate and legitimized prayer.

Fig. 6. Bible, Paris, related to Aurifaber workshop, ca. 1250-1300 (Hague MMW 10E 36 122r)

Meant as a companion to the text of I Kings 10, “As Anna had her heart full of grief, she prayed to the Lord, shedding many tears,” which precedes her vow, Hannah prays and Eli chastises, his finger as emphatic in scolding as her hands are clasped in prayer. Hannah is clearly the “negative exemplum to underscore the wisdom of adapting to the prescribed role.”[22] Eli watches her back how can he see her lips move in drunkenness? If she prays without sound, how disruptive can she be? But Eli corroborates that the appearance of impropriety is not actual impropriety; Eli defines the parameters of social prayer by scolding, by scrutinizing, and then by validating: “Go in peace: and the God of Israel grant thee thy petition, which thou hast asked of him” (I Kings 1:17). Indeed, Hannah counter confirms Eli’s propriety—a righteous man is obligated to reprimand a neighbor observed behaving in an unseemly manner.[23]

In this type, Hannah loses her social contexts of loving husband, aggressive rival, and miraculous son. She is embodied in her prayer—the Jerusalem Talmud exegesis specified that she prayed her heart, thus concentrating, that she moved her lips, thus pairing action with meditation, that her voice was not heard, humble before God not proud before her community, and that she was not drunk, as this is forbidden.[24] Gregory the Great similarly characterizes her as the contemplative life against Peninnah as the active life within the discussion of Elkanah/Christ as a model of prayer and fidelity.[25] Because Peninnah has children, she takes the role of activity, of living in this world; childless Hannah, fervent in her hopes that God will open her womb, instead becomes identified with contemplation and prayer. To Elkanah’s benefit, he favors the contemplative life through his prayers at Shiloh and his devotion to Hannah, even while faithfully performing his obligations in the active world through the distribution of portions to Peninnah and her children. Hannah bears Eli’s rebuke of drunkenness because patience is a virtue of the contemplative life; she prays without ceasing as proof of her complete devotion. The universality of Hannah as “Prayer” removes the particularity of her situation.

Fig. 8. Bible, Ile de France 1260-1270 (Princeton University Library, Garrett 82, f. 122v)

Variations to these types draw heavily on Byzantine canticle imagery[26] and tend to insert the figure of Christ/Logos (Figure 7 and Figure 8). In the Byzantine manuscripts which provide the model, the close physical connection to the canticle text provides a significant interpretive gloss that is missing when these images are moved to the earlier opening of the Book of Kings. In the canticle (1 Samuel 2: 1-10), the miracle has already been accomplished and Hannah is expressing her devotion: “My heart exults in the Lord; my strength is exalted in the Lord. My mouth derides my enemies, because I rejoice in thy salvation”(1 Samuel 2:1). Placing these canticle-reliant images in front of the earlier, pre-miracle text creates a gloss of granted prayer while showing Hannah’s error in improper prayer. God and Eli both hear her prayer, but, by facing Hannah, it is God who sees her heart.

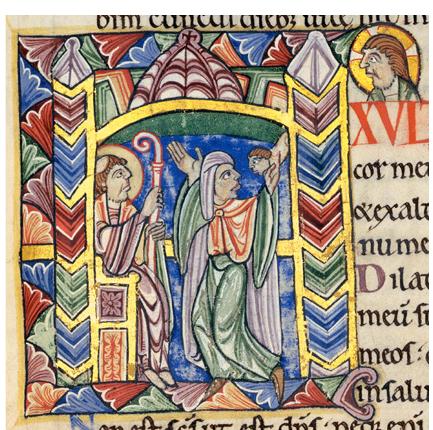

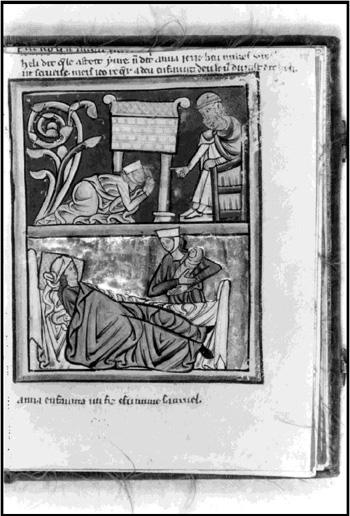

Fig. 9. Canticle of Anna, St. Alban‟s Psalter, 1135 (Aberdeen University Library MS 24)

In a book known for its woman’s emphasis, the ca. 1135 St. Albans Psalter made for Christina of Markyate,[27] the initial (Figure 9) does evoke the poignancy of the story, perhaps because it is presented outside the I Kings text, next to the Canticle of Anna. This unusual initial captures the contortion in the themes of social propriety and spiritual desperation. Part of Hannah acknowledges the respectable seated, tonsured, crosier-holding figure of Eli but her head turns back to the upper right where she reaches up her left hand to clutch a small naked figure. Outside the initial is the head of Christ-Logos. The St. Alban’s Hannah is submissive to authority while faithful in her devotion and thus proper prayers are directly fulfilled. The resonant themes of female significance throughout the St. Albans Psalter carry through to this canticle in its difficult physicality, the illumination stresses the suitability of clerical containment while grudgingly granting the spiritual richness of Hannah’s prayer and its reward.

Not a Woman but a Wife

If the context for Hannah’s desire for children is her status as a wife and mother, then what better way to safely encompass her scandalous behavior than to present it as a part of the prayer of her properly observant husband? Two illuminations exemplify the way husband and wife are visually placed together in a way that the text does not. The National Gallery’s leaf from the eleventh century (Figure 10), an Italian piece with strong Byzantine stylistic elements, places Hannah submissively behind Elkanah as both kneel in prayer before Eli; the scene directly below them shows Elkanah, not Hannah, holding the baby Samuel out to Eli. The Huntingfield Psalter (Figure 11), ca. 1210-1220, fuses two of the main iconographic trends, undoubtedly as a result of the circumstances of its creation at Lesnes Abbey (Kent) for Lucie, wife of Sir Roger de Huntingfield.[28] The upper scene preserves all of the monastic resonances of Elkanah/Christ flanked on his left by Peninnah/Synagogue and on his right by Hannah/Ecclesia and the embodiment of the women as vita activa Peninna actively eats and drinks and vita contemplativa—Hannah’s arms are folded tightly to her side as she inclines her head to Elkanah. In the lower scene, Peninnah does not appear. Hannah partly kneels far from the altar, her kneeling husband is interposed between her and the altar. Eli’s body is frontal but his eyes are on a level with Elkanah’s; Hannah’s eyes are slanted downward. Hannah’s scene has condensed her prayer with Elkanah’s expression of religious fidelity from Samuel 1:3. Because the text directs us that Elkanah is righteous, his presence gives Hannah’s prayer the added stamp of sanctity and social acceptability.

Fig. 10. I Samuel leaf, Italian, late 11th c. (National Gallery 1950.16.289)

Active thirteenth century workshops turned Hannah kneeling at the altar, her husband at her side, the couple both addressed by Eli, into a formula for the initial (Figure 12 and Figure 13). Peninnah is removed entirely from religious responsibility and action, emphasizing her spiritual deficiencies as unenlightened Synagogue. These workshop forms remove Hannah from a solitary position of spiritual privilege and divine blessing in order to emphasize her sacramental connection to her husband. Pushed back from the altar, Hannah is an echo of her husband; the act of her prayer is valued most in its reminder of the sacrament of a monogamous, hetero-normative, properly gender-structured marriage.

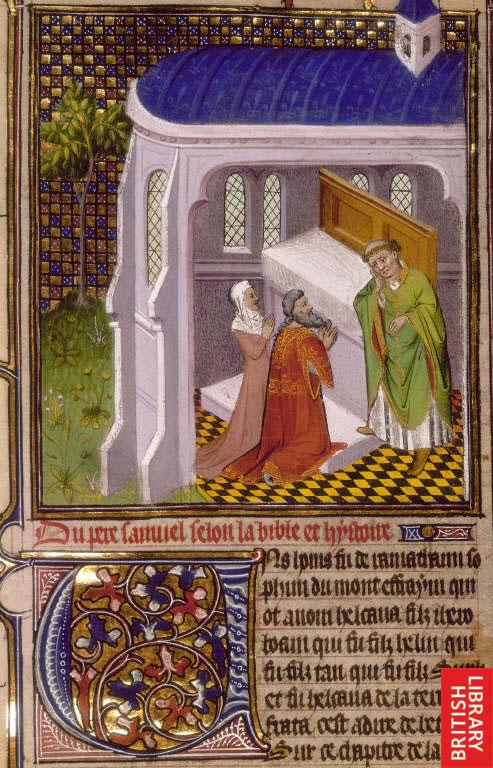

Indeed, the images become even more insistent that Hannah’s prayer not occur on its own as time progresses: in the Bible by the Fauvel Master, 1320-1340 (Figure 14), Elkanah prays to his idol on one side while Hannah prays to hers on the other.[29] They might be separated in direction with a thin column between them but the overlap of their kneeling bodies, the repetition of their gestures, and the color chiasm in their costumes says that her prayer is his prayer and his sanctity is hers. Petrus Ghilberti’s early 15th century historiated Bible (Figure 15) places them as a couple within a church, in front of an altar, before a tonsured priest who looks practically pained or shamed himself that he must admonish them.

Fig. 13. Bible, ca. 1297-1320, (The Hague RMMW, 10 E 32 fol. 109v)

Fig. 14. Fauvel Master workshop, Paris, 1320-1340 (The Hague KB 71 A 23)

Fig. 15. Petrus Gilberti, Historiated Bible, early 15th c. (British Library, Royal 15 D III, f. 112)

The appearance of this marital vocabulary in a standardized one husband/one wife before a priest form coincides with a wider cultural wave of ecclesiastical pressure to delimit and define the sacraments, including marriage. Coming from late eleventh century opposition over the Eucharistic Controversy and situated in the Scholastic codification of the twelfth century, theologians such as Peter Lombard and Hugh of St. Victor characterized marriage as instituted by the Lord “even before sin, yet not as a remedy, but as a duty”,[30] though it would be further discussed in the Augustinian fashion as both a remedy for incontinence in those who cannot keep from sin and a duty in those who faithfully increase and multiply. Notably, in order to describe the sacred sign expressed in marriage, Peter Lombard writes: “for the harmony of the husband and wife signifies the spiritual union of Christ and the Church which takes place through love; and the union of the sexes signifies the union which takes place through a conformity to nature”.[31] Further, this trend against polygyny can be seen in the Jewish community in Christian countries; Rabbi Gershom ben Judah (ca. 960-1028) codifies this tradition which continued through the Middle Ages.[32] Either as a mortal woman who will bear the miracle baby Samuel to her devoted husband Elkanah or as the Church personified married to Christ, Hannah fits the socially constructed model for sexual sanctity. Peter Lombard addresses the issue of sexual union and Gratian in the twelfth century and other canonists in the thirteenth and fourteenth century stress the legal issues of creating a contractually valid bond, which entailed moving marriage from the individual context to the socially regulated sphere in the presence of the priest as an authority.[33] The increased public nature of weddings, combined with a sacramental concern within the orthodox Church, may account for the way in which the Hannah and Elkanah image is constructed to emphasize monogamous marriage in the presence of a priest.

Like the demographic shift that creates a change from large scale presentation Bibles to small scale personal devotional books, we might see a similar shift in that these later illuminations draws heavily on the new source of the Bible Historiale. Noting the narrative approach to these Bibles, which were written in the vernacular with glosses and clearly intended for a lay audience, Libby Karlinger Escobedo sees the presence of women particularly as visual role models for the medieval female reader.[34] The stylistic conventions created in this source are widely copied and disseminated, creating an iconography of Hannah which marries her more strongly to her husband while divorcing her from her textual context.

Fig. 16. Bible; late 13th c. (Princeton University Library Garrett 29, f 157r.)

Can Hannah own her own prayer? Can she be the singularly strong woman who endures the pain brought by infertility in a society that defines female identity through child-bearing and rearing? This isolated example in a Bible from the late thirteenth century (Figure 16) seems to show agency—she kneels, with active engaged gestures, before a cloth covered table. But does she really own this prayer? The illumination takes the story out of its context. No co-wife to taunt her, no husband to coddle her, no children to be ogled, no clerical figure to chide her, no God to hear her prayer, no Samuel to be granted for her faith. She is in fact alone and the table lacks the context of an altar so Hannah’s prayer moves back from the sphere of the public to the private; without witnesses, without ecclesiastical setting, she no longer broaches the delineated role for women’s prayer. Though we don’t know the provenance of this particular Bible, it is not hard to postulate a female patron seeing her own prayer modeled in the heroines of the Bible, in the mode of a Jeanne d’Evreux.[35] The illumination models proper prayer rather than reporting Hannah’s actual prayer.

Even when constrained within the strictures of these visual models, Hannah spoke to her readers. Several of these images show wear consistent with rubbing or touching the image. The William de Brailes leaf in the Walters collection (Figure 17), ca. 1230-40, shows this clearly: the face of Hannah is abraded as she kneels abjectly before the altar and accepts the castigation of Eli.[36] Below the scene is the fulfillment of Hannah’s prayer in the birth of Samuel.

Fig. 17. William de Brailes, leaf, ca. 1230-40 (The Walters Art Museum W106/W500 fol. 17r)

We can imagine a reader caught by the social and personal pains of infertility reaching out to Hannah in her desire for the success Hannah’s prayer gives her. It is precisely this desperation of Hannah’s heart driving her to cross social boundaries which appeals to modern women writing about infertility:

Her heart petitioned the name too holy to voice, “Yahweh, will I ever have a labor story to share with the women at the city well? How I long for morning sickness! Will I never know the joy of snuggling my child to my breast? Could it truly be that I may never watch my own chubby-legged infant attempt his first tottering steps? Will Elkanah ever have the chance to direct our offspring in Your ways? Will I ever cry as I send my son off to his first day of studying the Torah? Might I never be mother of the bride? A lifetime of losses overwhelmed Hannah. As she grieved for the child who was not, Elkahnah’s attempts to comfort her were futile. Distraught beyond words, absorbed in prayer, now she must muster a defense against Eli’s misjudgment.[37]

Hannah has the potential to be a Margery Kempe—extravagantly dramatic in her devotion to the fervent indignation, annoyance, and inspiration of those around her. Intense, unbounded piety causes disruption—in the normal gendered roles, in the normal worship, and therefore, in the cultural desire for equilibrium and inertia. Medieval images of Hannah crave that stability: showing little visual variation, aimed at promoting interpretive rubrics as Ecclesia and the Virgin Mary, re-formulating the textual narrative to create an image of prayer within the sanctities of marriage. Hannah’s childlessness and her marriage are clearly shaped by the dynamics of object-relations theory; she is the median between two poles: “the desire for the nurturance represented and promised by the preoedipal mother and for the power and autonomy associated with the oedipal father”[38] Hannah wants a child. She wants the marriage offered by Elkanah. The problem becomes the degree to which she usurps the power and autonomy of men in order to achieve the goal of mothering. Medieval images are clearly designed as “visual analogues”[39] that allow a multi-faceted layering borrowing from narrative to circumscribe behavior in order to uphold social order. In the monastic audience, Hannah becomes the Church in order to dissociate her from her gendered secular identity and allow men to claim this identity through their own participatory prayer. The removal of Peninnah creates a more recognizable construction of the normative medieval marriage; there is nothing transgressive in Hannah’s desire for a child—it is her normative heterosexual position. The containing of Hannah with male authorities delimits social behavior: wives must be subject to their husbands, clerics must be mindful of their parishioners. “Embedding didactic images in the devotional text…would keep the lessons in mind, and prayer and visual exempla worked together toward the same end, the construction of gender.”[40]

References

| ↑1 | Leilah Leah Bronner, “Remember thy handmaid: Hannah on Prayer”, From Eve to Esther: Rabbinic Reconstructions of Biblical Women (Louisville, 1994), 95-6. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Augustine, De Civitate Dei, Book X:14. |

| ↑3 | C.M. Kauffmann,“The Bury Bible (Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS. 2)”, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 29 (1966): 60-81 was followed by C.M. Kauffmann, “Elkanah‟s Gift: Texts and Meaning in the Bury Bible Miniature”, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 59 (1996): 279-285, which places the imagery into the context of medieval gift economies. https://doi.org/10.2307/750709 |

| ↑4 | ”“Anagogical”, Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House, Inc. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/anagogical (accessed: May 27, 2010). |

| ↑5 | Esther Fuchs, Sexual Politics in the Biblical Narrative: Reading the Hebrew Bible as a Woman (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2000), 90. The feminist analysis of Hannah has an extensive bibliography; see the following articles in Athalaya Brenner, ed., A Feminist Companion to Samuel and Kings (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1994): Yairah Amit, “Am I not more devoted to you than ten sons? (I Samuel 1:8): Male and Female Interpretations”, 68-76; Lillian R. Klein, “Hannah: marginalized victim and social redeemer”, 77-92; see also Carol Meyers, “Hannah and her sacrifice: reclaiming female agency”, 93-104. See also Cynthia Ozick, “Hannah and Elkanah: Torah as the matrix for feminism” in, Out of the Garden: Women Writers on the Bible, ed. Christina Büchmann (New York: Fawcett Columbine, 1994). The following bibliography also addresses Hannah as part of comparative analysis of other female characters, particularly as barren mothers: Esther Fuchs, “The Literary characterization of Mothers and Sexual Politics in the Hebrew Bible”, in, Feminist Perspectives in the Hebrew Bible, ed. Adela Yarbro Collins (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1985); Mary Calloway, Sing O Barren One’ A Study in Comparative Midrash (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1986), Katheryn Pfister Darr, Far More Precious Than Jewels: Perspectives on Biblical Women (Louisville: Westminster/John Knox Press, 1991), and J. Cheryl Exum, Fragmented Women: Feminist (Sub)versions of Biblical Narratives (Valley Forge: Trinity Press International, 1993). |

| ↑6 | Meir Bar Ilan, Some Jewish Women in Antiquity (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1998), 112-113. See also Dvora Weisberg, “Men Imagining Women Imagining God: Gender Issues in Classic Midrash”, in Agendas for the study of Midrash in the Twenty-First Century, ed. Marc Lee Raphael (Williamsburg: College of William and Mary, 1999), 63-83. |

| ↑7 | Explicitly occurring in silence because of her humility, it begins as a petition with an acknowledgement of that piety: “Did you not, Lord, search out the heart of all generations before you formed the world? Now what womb is born opened or dies closed unless you wish it? And now let my prayer ascend before you today lest I go down from here empty, because you know my heart, how I have walked before you from the day of my youth.” (Markus McDowell, Prayers of Jewish Women: Studies of Patterns of Prayer in the Second Temple Period (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2006), 105). See also Joan E. Cook, Hannah’s Desire, God’s Design: Early Interpretations of the Story of Hannah (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1999). |

| ↑8 | Jane Tibbets Schulenberg, “Female Sanctity: Public and Private Roles”, in Women and Power in the Middle Ages, ed. Mary Erler and Maryanne Kowaleski (Athens: University of Georgia, 1988), 117. Schulenberg’s analysis of sainthood and female identity shows the dramatic changes from public to domestic spheres, with ramifications for claustration, education, and economics. |

| ↑9 | A partial list of these Bibles illuminated in the British Isles includes the Rochester Bible (B.L. Royal I.C. vii) from ca. 1130, the Bury Bible (Corpus, Cambridge, ms. 2) from ca. 1135, and the Winchester Bible (Winchester Cathedral) from ca. 1150-1180. There is also a vibrant Continental tradition which includes the eleventh-century Stavelot Bible (BL MS Add 28107, fol. 97), the late twelfth-century St. Omer Bible (Paris BN MS lat 7) and the Laud Bible (Bodley, Laud misc. 752) from 1180, which was once considered to be English but is now thought to be French. There are many other illustrated Romanesque Bibles whose volumes are not extant for the Book of Kings so the number of Hannah illustrations might have been markedly larger. For a chart of Old Testament iconography in Romanesque Bibles, see C.M. Kaufmann, Romanesque Manuscripts 1066-1190 (London: H. Miller, 1975), 40-41. For more on the Bible production of the period, see also Walter Cahn, Romanesque Bible Illumination (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1982), Peter Brieger, “Bible Illumination and Gregorian Reform”, Studies in Church History II (1965), 154-164 , and Margaret Gibson, The Bible in the Latin West (Notre-Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1993). |

| ↑10 | Interestingly, Peninnah’s gesture closely parallels that of Hannah; her hand reaches up to her eyes, although she lacks a sad expression and is not holding her coif as a handkerchief. Peninnah’s parallel mannerism may be read as mocking Hannah, as a parody of Hannah’s gesture, thus closely referencing the text of 1 Kings 1: 6-7. This is also a way of creating Peninnah as the negative opposite to Hannah so that Peninnah can be seen as Synagogue despite not being depicted with the standard medieval attribute of the blindfold. |

| ↑11 | Gregory the Great PL 79, 1047. |

| ↑12 | Gregory the Great PL 79, I,3 (8,3) |

| ↑13 | Walter Cahn, Romanesque Bible Illumination, 184. |

| ↑14 | Leila Leah Bonner, “Remember thy Handmaid: On Hannah and Prayer”, 94. |

| ↑15 | Sarah Bromberg, in her article “Gendered and Ungendered Readings of the Rothschild Canticles” (Different Visions, 1 (2008), has argued the theory for seeing male identification with the Sponsa, an idea that is clearly transferrable to the image of Hannah, especially in an image that deliberately decontextualizes her biological role of pregnancy and child-rearing. https://doi.org/10.61302/PMSR4045 |

| ↑16 | Some question as to whether the page was ever part of the Bible; for differing viewpoints, contrast Larry M. Ayres, “The Work of the Morgan Master at Winchester and English Painting of the Early Gothic Period”, Art Bulletin 56/2 (1974), 201-223 and Claire Donovan, The Winchester Bible (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993), 33. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.1974.10790032 |

| ↑17 | Lillian Klein, From Deborah to Esther, 53. |

| ↑18 | Augustine, De Civitate Dei, book XVII, chapter 4. |

| ↑19 | For example: Paris BN lat 15, a Bible from the first half of the thirteenth century; Paris BN lat 16743-6, a Bible of the twelfth to thirteenth century; BL Stowe 1, a Bible of the second half of the thirteenth century; and the Psalter of St. Louis, Paris BN 10525, from the second half of the thirteenth century. |

| ↑20 | See R. Milburn, “The ‘People‟s Bible’: Artists and Commentators”, in Cambridge History of the Bible, volume 2, ed. G. Lampe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975); Robert Branner, Manuscript Painting in Paris during the Reign of St. Louis: A Study of Styles (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977); Christopher de Hamel, Glossed Books of the Bible and the Origins of the Paris Booktrade (Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 1984); and Christopher de Hamel, A History of Illuminated Manuscripts (London: Phaidon, 1994). |

| ↑21 | Women and the Book: Assessing the Visual Evidence, eds. Jane H.M. Taylor and Lesley Smith (London: British Library Studies in Medieval Culture, 1997). Three essays are most pertinent here: Richard Gameson, “The Gospels of Margaret of Scotland and the Literacy of an Eleventh-Century Queen”, pp. 149171, offers a view of reading as connoting devotional practice and the possibility of loose ties between that practice and actual literacy; Anne Rudloff Stanton, “From Eve to Bathsheba and Beyond: Motherhood in the Queen Mary Psalter”, pp. 172-189, presents a fourteenth-century example of the use of images to reinforce ideals of proper female behavior and which includes Hannah’s presentation of Samuel in the Temple; and most importantly, Sandra Penketh, “Women and Books of Hours”, pp. 266-281, who traces patterns of ownership and inheritance of Books of Hours, their devotional use by women, and instances of their moral instruction of their readers. For more on medieval female ownership of books, see S.G. Bell, “Medieval Woman Book Owners: Arbiters of Lay Piety and Ambassadors of Culture”, in Sisters and Workers in the Middle Ages, ed. J.M. Bennett (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989), pp. 135-161. |

| ↑22 | Pamela Sheingorn, “The Maternal Behavior of God: Divine Father as Fantasy Husband”, in Medieval Mothering, ed. John Carmi Parsons and Bonnie Wheeler (New York: Garland, 1999), 91. |

| ↑23 | Babylonian Talmud, Leilah Leah Bronner, “„Remember thy handmaid‟: on Hannah and prayer”, 96 |

| ↑24 | Jerusalem Talmud, in Leilah Leah Bronner, “„Remember thy handmaid‟: on Hannah and prayer”, 95. |

| ↑25 | Gregory the Great, PL 79, 64.1. The section of the text focuses primarily on Elkanah as a model of prayer and religious fidelity; the women are treated more as subsidiary virtues of that characterization. |

| ↑26 | As seen in manuscripts such as the 1074-1081 Psalter (Leningrad gr. 214), or the 1084 Psalter (Dumbarton Oaks 3, fol. 75 r) (Index of Christian Art). |

| ↑27 | M.H.Caviness, “Anchoress, Abbess, Queen: Donors and Patrons or Intercessors and Matrons?‟, in The Cultural Patronage of Medieval Women, ed. June Hall McCash (Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 1996), 105-153, M.E.Carrasco, “The Imagery of the Magdalen in Christina of Markyate’s Psalter (The St Albans Psalter)‟ Gesta, xxxvii, 1999, 67-80, and K.E. Haney, The St. Albans Psalter: an Anglo- Norman Song of Faith (New York: P. Lang, 2002). For Byzantine influences, see Otto Pächt, C.R. Dodwell, F. Wormald, The St Albans Psalter (Albani Psalter) (London: Warburg Institute, 1960), Otto Pacht‟s discussion of the links between Romanesque Bible illumination and Byzantine illuminations in Bibles and Psalters in Book Illumination in the Middle Ages (London: H. Miller, 1994) and Kurt Weitzmann, “The Illustration of the Septuagint”, Studies in Classical and Byzantine Manuscript Illumination, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1971) 59. |

| ↑28 | Manuscript CORSAIR record description, Morgan Library, http://corsair.morganlibrary.org/msdescr/BBM0043a.pdf, accessed 6/3/10. |

| ↑29 | Interestingly, Hannah’s idol wears a crown, a clear reference to the role Samuel plays in the political future of Israel. |

| ↑30 | Peter Lombard, Distinction 26:1, quoting Hugh of St. Victor; Elizabeth Rogers, Peter Lombard and the Sacramental System (Merrick: Richwood, 1976), 243). |

| ↑31 | Peter Lombard, Distinction 26: 6. |

| ↑32 | Judith Baskin, “Jewish Women in the Middle Ages”, in Jewish Women in Historical Perspective, ed. Judith Baskin (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1998), 109. |

| ↑33 | Frances and Joseph Gies, Marriage and the Family in the Middle Ages (New York: Harper & Row, 1987), 138-141, 218-219. See also Michael Sheehan, “Choice of Marriage Partner in the Middle Ages: Development and Mode of Application of a Theory of Marriage”, Studies in Medieval and Renaissance History 11 (1978): 4-15. |

| ↑34 | Libby Karlinger Escobedo, “Heroines, Wives, and Mothers: Depicting Women in the Bible Historiale and the Morgan Picture Bible”, in Between the Picture and the Word, ed. Colum Hourihane (University Park: Penn State Press, 2005) 100-111. |

| ↑35 | Madeline H. Caviness “Patron or Matron? A Capetian Bride and a Vade Mecum for Her Marriage Bed.” in Studying Medieval Women: Sex, Gender, Feminism, ed. Nancy F. Partner (Cambridge: Medieval Academy of America, 1993), 31-60. https://doi.org/10.2307/2864556 |

| ↑36 | Signs of apotropaic touching have been suggested for other scenes in this manuscript; William Noel, The Oxford Bible Pictures from the Walters Art Museum (Luzern: Faksimile Verlag Luzern and the Walters Art Museum, 2004), 98. |

| ↑37 | Jennifer Saake, Hannah’s Hope: Seeking God’s Heart in the Midst of Infertility, Miscarriage, and Adoption Loss (Colorado Springs: NavPress, 2005), 145-146. |

| ↑38 | Pamela Sheingorn, “Maternal Behavior of God: (the) Divine Father as Fantasy Husband”, 84. |

| ↑39 | Pamela Sheingorn, “Maternal Behavior of God: (the) Divine Father as Fantasy Husband”, 83. |

| ↑40 | Madeline Caviness, “Patron or Matron? A Capetian Bride and a Vade Mecum for Her Marriage Bed”, 41. |