Aura and Absence

Spending the summer on Samothrace was one of the highlights of my life. The work itself was interesting, if somewhat tedious since we were studying, cataloguing, and conserving objects rather than actually digging. But what I especially remember about Samothrace are images and experiences that bore into my soul: the spectacular site with its marble ruins set against the blue Aegean, flanked by mountains perfumed with oregano and visited by goats adorned with tinkling bells; the calamari and ouzo consumed at day’s end; and the remarkably sympatico company (Fig. 3).

We did not go to Samothrace this summer. Sometimes I follow the advice of Agatha Christie, the wildly successful writer of detective novels, and also the wife of the archeologist Max Mallowan, famous for his work at Ur, Nineveh, and Nimrud. She wrote in her autobiography, “Never go back to a place where you have been happy. Until you do it remains alive for you. If you go back it will be destroyed.” For me, there is an aura about Samothrace that can only be preserved if I never go back there again, if I remain absent. It may be physically destroyed as a ruin, but it lives on in my memory as a place of pure, sun-splashed happiness.

And of course, the Nike herself is absent from Samothrace, but her aura haunts the entire site. The little museum there attempts to capture some of her authoritative presence with a plaster cast, but her boldly saucy wet t-shirtedness is resigned to a dreary corner (Fig 4). Nearby, fragments of the original sculpture lie forgotten in a glass case. Relics of the real; the presence of the absent. Walter Benjamin (and John Berger) might argue that the aura of the original is absent in the reproduction, that we privilege the authentic even if it is cheapened in the modern possibilities of multiplicity through casts, postcards, and the like. But I think I’m talking about a different kind of aura – an aura that is felt in both the body and soul, that transcends the object to inhabit the place itself.

There were other places we saw this summer in Greece that also struck me as having a remarkable mix of aura and absence. Delphi as a place of prophecy was one of the most important sites in the ancient world, where people made pilgrimages to consult the oracle.

Fig. 5. Delphi, Greece

It is still a place which inspires extraordinary emotion; a visitor there feels that the rugged vistas must be very similar to what the ancient Greeks themselves experienced, with the dry winds sighing in the cypresses and hundreds of ancient olives spread wide on the plain below; in the distance the blue sea and the visible outline of the silted-in harbor where ancient ships anchored. The world of the present barely intrudes, the museum building out of sight the higher one climbs into the sanctuary that spills down the mountainside (Fig 5). The sanctuary buildings themselves are in ruins, mostly foundations with bits re-erected here and there to satisfy the need to see and know what was once there. The temple of Apollo, the location of the oracle, was destroyed by Theodosius I in 390 CE in the name of Christianity, and earthquakes finished the job; even before that, sculptures and other elements of the sanctuary were carted away, including the famous bronze Serpent Column which supported a golden tripod and bowl, taken from Delphi by Constantine the Great to grace the hippodrome in Constantinople, where it still stands (Fig. 6). But the absence of the architecture in no way detracts from the aura of the place. In fact, it is what is missing that augments the sense of poignancy that is nearly palpable.

Fig. 6. The Serpent Column

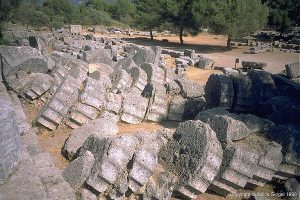

Of course any sort of ruin speaks of absence, of what was and is no longer. At various points in history, the ruin itself has been revered as a reminder of past great civilizations, or incorporated into landscape design as follies, as elements of the picturesque. Even Hitler supposedly wanted buildings designed so that they would look attractive after they became ruins in time. Our trip through Greece took us to many places in ruins: Akrotiri on the island of Santorini, Olympia, Epidaurus, Mycenae, and Athens, in addition to Delphi. The ruins of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia were particularly striking since for the most part, the column drums were left as they fell after the destruction of the sanctuary ordered by Theodosius II, as well as subsequent earthquakes (Fig. 7). But some places seem to transcend their ruins, to be imbued with a spiritualized force that makes meaning beyond the physical remains.

Fig. 7. Column drums Olympia

After long days at work on Samothrace, and after leisurely outdoor dinners that began with ouzo at sunset and ended with wine by starlight, the long-time architect at the excavations, the wonderful John Kurtich would muse in the dark about the otherworldly pull of the place. He spoke to us of ley lines, originally described in Alfred Watkins’ Early British Trackways. Watkins postulated that prehistoric people navigated by a series of points and alignments that often included the tops of hills and other such locations, ultimately forming a series of trackways that connected via straight lines, which he felt were still visible in both natural features and human interventions in the landscape. Over time these speculations were embraced by others, and the significance of ley lines expanded far beyond anything that Watkins intended, even into the paranormal, so that places of great historical and spiritual significance are postulated to have been built in particular places almost inevitably; their siting at specific geographic locations a function of the power and energy that exudes from the places themselves. (Dan Brown popularized this idea in The Da Vinci Code with his invention of the Rose Line running through Paris.) Stonehenge, the pyramids, Mont-St-Michel, Glastonbury Abbey, Chartres Cathedral, Machu Picchu, and yes, Delphi and Samothrace, all have been identified as existing on ley lines. It was never clear to me that John, as incredibly learned as he was, really believed this, but he had spent so many years at the site that its mystical aura enfolded him even more deeply than it did us.

Fig. 8. Roger Waters performing “The Wall”

On our last night in Athens, at the urging of our 15-year-old electric guitar-playing son, we went to hear Roger Waters perform “The Wall” at the new Olympic Stadium. As the performance proceeds, stone by stone, a giant wall is erected across the stage, ultimately obscuring the musicians, and even Roger Waters himself, from the audience. The wall becomes a projection screen, most dramatically during the intermission, when images of people killed in various wars fill the screen. Ultimately, at the climax of the concert, the wall is torn down and huge blocks tumble across the stage and even into the audience, leaving behind a ruin, the absence of the music eclipsed by the aura of euphoria left in the stadium (Figs. 8 and 9). It seemed a fitting end to our trip.

Fig. 9. “The Wall” comes down