Post-Mortem on an Undead Exhibition: “Art That Kills”

Once, while we were both in college, I went to visit my best friend from high school at Princeton University. Knowing I loved art, and loving it himself, Scott walked with me around campus to look at the first-rate sculpture collection there. All the sculpture-park biggies are there: Moore, Serra, Lipschitz, Smith, Nevelson, and the other Smith. And Calder. As we were looking at that one, Scott told me he had heard that two workers had died during the installation of the sculpture.

“And they kept it?” I asked, suddenly feeling a bit wary around the thing.

“Of course they did,” replied Scott, somewhat bemused. “It’s a Calder!”

“Still…” I answered. “Bad mojo.”

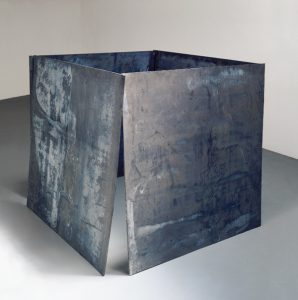

Richard Serra, “House of Cards (One Ton Prop),” 1968-69, lead. Museum of Modern Art

Not long after that I learned about another art-related tragedy. During Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s installation of large umbrellas in California and Japan, one of them came unmoored in a windstorm and crushed a woman. Not long after, I came across Richard Serra’s House of Cards, which killed an art handler when one of the lead plates comprising the sculpture fell on an art handler, due to a gaffer’s error.

I became somewhat obsessed with the idea of artworks that had killed people. Part of it must have been the disillusionment of realizing that not all art was always transcendent and uplifting (I was, remember, an undergraduate). Also, accustomed as I was to seeing works of art in reproduction, I think the brute physicality of these tragedies also fascinated me. These works of art were also massive things, which could be dangerous if mishandled.

Robert Arneson, “Chemo 2,” 1992, glazed ceramic. SFMOMA

Robert Arneson, “Chemo 1,” 1992, glazed ceramic. SFMOMA

Over the next few years, I kept my eyes open for other stories of artworks that had played a role in someone’s death. While I initially had been thinking about blunt sculptural trauma, I gradually came to realize that a lot of artworks were poison, too. As our own Nancy Thompson pointed out to me, the 19th-century glass artist Giuseppe Francisci apparently died from exposure to toxic gasses in his studio; perhaps there were others. A sculpture professor told me of widespread suspicions that Eva Hesse’s early death from cancer could be traced to her working with polyester resin and fiberglass without adequate protective gear and ventilation. A ceramist said the same worries had come up around Robert Arneson’s long struggle and eventual death from cancer. I remember vividly standing before Arneson’s harrowing Chemo I and II self-portraits and wondering if the sculptures before me–particularly their sickly, toxic glazes–hadn’t hastened his demise just as they were communicating his humanity.

And then of course there’s Vincent van Gogh, who has long been suspected of having suffered from lead poisoning from his paints, among other ailments. That poisoning has been both credited for influencing his palette and technique and also blamed for causing the psychosis that may have led to his suicide. Caravaggio and Goya have also been picked out as possible sufferers from lead poisoning, though of course this is all modern speculation, much of it tied up in popular romantic notions of the tragic genius.

Still, imagine for a second walking into a room filled with paintings and sculptures–one that didn’t look too much unlike any other gallery (save perhaps for a curious mixing of genres and time periods)–and then slowly realizing that every object you were looking had killed, or at least aided and abetted in a death. How would that feel? People tend to give Richard Serra’s pieces a wide berth (the one time I saw House of Cards, it was roped off so that you couldn’t get within six feet of it), but would they similarly avoid Sunflowers?

I considered seriously pursuing this topic for my Master’s thesis, but was talked out of it by a classmate (“C’mon, man. What’re you going to waste your time with that for?”). Which was probably for the best; I couldn’t have done justice to the topic at the time. I hadn’t yet encountered Alfred Gell, Bruno Latour, Ian Hodder, or the many other thinkers who would have helped me bring the idea to life. Later, while I was working as a curator, I realized that the exhibition could never be staged anyway: there’s no way people would lend the works. And in my mind it has to be an exhibition. We have to encounter the real things, not some mug shots in a book.

And I’ve come to realize that there’s a bigger problem. Even though now I’m familiar with concepts like object agency, reception, the medieval law of the deodand, and object history, I really don’t understand death. Granted, no one does. Over the years since I first thought of this idea, I’ve lost several people close to me, so, yes, I’m starting to know what that’s like to lose someone. But I don’t think I have it in me yet to do justice to the memory of the people killed by these works. How could I stage this exhibition without sensationalizing or diminishing their deaths? How could I talk about this topic without perpetuating the myth of the tragic artist, or, perhaps just as unfortunately, explaining that myth away through forensic pathology?

Though I do think there’s a lot to be got out of it, I’ve come to accept that this is a project I’ll probably never pursue. At the same time, I don’t think I’ll ever let it go. So I’ll let it stay undead for a while, and maybe someday I’ll bring it back to life.

Or maybe it’ll just eat my brain.