Charles Nelson • Tufts University

Recommended citation: Charles G. Nelson, “Are We Being Theoretical Yet? Innocents Abroad and Sachsenspiegel Scholarship,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 1 (2008). https://doi.org/10.61302/JTBM7379.

The purpose of this paper is twofold: first to establish briefly a theoretical and historical context for Madeline Caviness’s Triangulation theory; second to demonstrate more expansively an aspect of that theory—namely to exploit theoretical “concepts that had not been entertained at the time the work was created.[1] This will involve a textual analysis of the Sachsenspiegel law book based on contemporary speech act theory. The results of the use of this theory will reveal issues surrounding the thirteenth-century historical initiative to record Saxonian customary law.

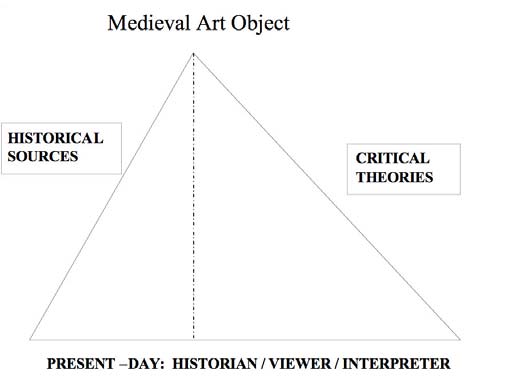

Before employing that critical theory, it will be helpful to associate it with the triangular frame (Figure 1) devised by Madeline Caviness to present graphically her understanding of a valid approach to the study of medieval objects of art, which idea the contributions in this volume are exploring and celebrating. At the apex of the triangle, there perches a “medieval art object,” One of the major contributions of the triangle is that its apex is not necessarily limited to medieval art objects, which enables me to substitute the word “text” for “art” thus legitimizing speech act theory analysis.

Fig. 1. Triangle, From Madeline H. Caviness, Reframing Medieval Art: Difference, Margins, Boundaries, e-book, http://dca.lib.tufts.edu/Caviness, 2001.

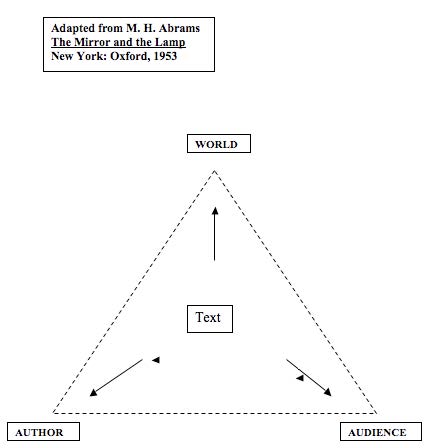

Attributes of the Caviness post-modern Triangle will stand out more clearly if compared to an earlier one based on decades-old conventional, pre-New Historical assumptions on the nature of literary texts. This triangle appeared in the introduction to M. H. Abrams’s 1953 book on English Romantic criticism, The Mirror and the Lamp.[2] He entitled the introduction “Orientation of Critical Theories.” Under the sub-title “Some Co- Ordinates of Art Criticism” he writes:

Four elements are discriminated . . . in almost all theories which aim to be comprehensive. First there is the work, the artistic product itself…the second common element is the artificer, the artist. Third, the work is taken to have a subject…to be about, or signify, or reflect something…an objective state of affairs. This third element has been . . . denoted “nature”…;but let us use universe instead. For the final element we have the audience: . . .

He spoke of a triangle, but since he did not actually draw one, I have added a phantom figure (Figure 2), using dotted lines. And I substituted a more modest “world” for his “universe,” (itself his substitution for “nature”) and updated his “work” with Roland Barthes’ “text.”[3] He goes on to elaborate on four “orientations of critical theories.” His definition of theories is limited to what critics thought and understood about art and literature. He identifies as “mimetic theories” those that explore how the work relates to the world (8); as “pragmatic theories” those that are interested in art as a means to an end and its effects (14); and as “expressive theories” those that locate the artist “himself “(!) as the place to look for meaning and value in the “artistic product” (22). The “objective orientation” on principle regards the work of art in isolation from all these external points of reference, analyzes it as a self-sufficient entity constituted by its parts in their internal relations, and sets out to judge it solely by criteria intrinsic to its own mode of being” (26).

For Abrams in the 1950s in the United States, the decade before European theory invaded the field, the study of literature was split by divisive commitments to either extrinsic or intrinsic approaches to the study of literature, with the post World War II generation led by the disciples of the American New Critics (R. P. Blackmur, Cleanth Brooks, John Crowe Ransom, Allen Tate, et al.) tipping the balance in favor of their style of Formalism.[4] In the late 1980s Carolyn Porter, a critic and historian of English and American literature, in an article whose title inspired mine, “Are We Being Historical Yet?” spoke of the relation in the 1970’s “between the historical conditions of a particular text’s production and reception at a moment in the past and the historical conditions of the present out of which our concern with that text arises.”[5]

Fig. 2. Triangle, Adapted from M.H. Abrams, The Mirror and the Lamp (New York: Oxford, 1953).

Madeline Caviness has been responding in her own work to that very emphasis beginning, notoriously as it turned out, with her Jeanne d’Evreux article in 1993.[6] In 1997 in “The Feminist Project” she offers a model, elegant in its simplicity, for approaching objects of medieval art.[7] A comment by Jane Flax on postmodernist approaches fits Caviness’s proposal to the letter. She (Flax) speaks of the postmodernists’ “refusal to avoid conflict and irresolvable differences or to synthesize these differences into a unitary, univocal whole.”[8] Precisely in this mode, Caviness actually foregrounds the postmodern tension between historicizing and theorizing in the act of observation.

Abrams’ 1950’s model derived from a Positivist paradigm in debt to the Enlightenment meta-narrative, a paradigm which sees phenomena external to the work of art as causal in its production.[9] Caviness’s model half a century later is less interested in the nature of the object to be studied than in “concepts that had not been entertained at the time the work was created, and it owes its power to its predisposition not to look for unity within medieval culture. Abram’s triangle reflects the Formalism and Old Historicism of the 1950s; Caviness’s “the tension between postmodern theory and ‘history’“[10]

The older paradigm was deserted by some, perhaps, but not by all. Some reading this essay may have also attended the 2006 Annual Meeting of the Medieval Academy in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Those who found themselves listening to some of the papers I heard will have a short easy answer to the question posed in my title, “Are We Being Theoretical Yet?” Some are, some are not. It is a persistent problem: Old Historicists versus New Historicists/Theorists. In one of the Medieval Academy sessions, a historian of the old school paused in his delivery of a paper on royal power to complain “that you can’t talk about power anymore without using the F-word” – a word that turned out to be Foucault. He performed his annoyance with an exasperated shrug and skyward glance – to the accompaniment, literally in one case, of thigh-slapping approval and raucous laughter, possibly imagining another F-word in position before “Foucault.”[11]

At this point I have reached the second purpose of this paper, namely to apply contemporary speech act theory in the analysis of particular speech acts incorporated into the first written version of Saxon customary law, the Sachsenspiegel.[12] The Sachsenspiegel “law book” or Rechtsbuch, is a compilation of thirteenth-century German customary laws written in the vernacular by Eike von Repgow between 1220 and 1235.[13] This influential text survives in 460 manuscripts (including fragments) which continued to be produced until the advent of printing in the fifteenth century.[14] Four of them, ranging in date from about 1290-1370, are very densely illustrated on every page of the main text.[15]

A veritable mountain of research already exists on the Sachsenspiegel, produced primarily by senior German legal scholars and philologists whose interests reflect its established status as one of the most important monuments in the history of German law and as one of the earliest prose works in the German language.[16] When we initiated a dialogue with our German colleagues who had addressed the Sachsenspiegel in their research, all of them welcomed us warmly.[17] We explained that we are focusing on the picture books and that because our approach to them is based on contemporary theory, we hope to add something of value to previous scholarship.[18]

With the caveat that I am not a legal historian, I will venture to say (again) that none of the historical work on it takes postmodern theory into account. I am also not able to say whether or not this historical work is a Sonderweg (special approach) taken by these historians among others in Germany. The nonetheless superb scholarship, for example that which produced the facsimiles and their commentary volumes, makes projects like ours possible.[19] Indeed it was the hope of the team that produced them that scholars in other fields would be encouraged to work on the picture books. And so with others, we stand at the base of the postmodern triangle; we incorporate the historical research, and by activating the theory lever are able tell another and different kind of story about the Sachsenspiegel picture books.

And so to the question of how to avoid the Formalist trap when analyzing Eike’s language: first, refrain from resorting to uniquely literary critical discourses, e.g. the New Critics’ interest in irony and paradox; and second, perform a close reading making use of another discourse, in this case, a philosophical one as it articulates speech act theory.[20] As I hope to demonstrate, conclusions derived from application of this theory avoid the subjective aesthetic judgments which Porter finds inimical to legitimate historical criticism of social texts. One of those conclusions is that at the fundamental level of the structure of Eike’s speech itself one can perceive what appears to be a personal anxiety concerning both his and his book’s authority in the Saxon world.

Before I can demonstrate that, I will review briefly what speech acts are with examples from Eike’s running comments on the law, his role in recording it, and his authority to undertake and complete the project, but first, a few technical definitions of speech act theory are in order. John L. Austin famously distinguished between statements that described a state of affairs in the world as constative (saying something) or performative (doing something).[21] A constative utterance describes a state of affairs and makes a statement that can be said to be true or false. A performative utterence performs an act as with the expression “I promise,” that performs the act of promising. A locutionary act is the act of conveying semantic content in an utterance, considered as independent of the interaction between the speaker and the listener; an illocutionary act pertains to a linguistic act performed by a speaker in producing an utterance, suggesting, warning, promising, or requesting. A perlocutionay act produces an effect upon the listener, as in persuading, frightening, amusing, or causing the listener to act. Eike’s role as narrator/commenter/recorder interjects numerous examples of illocutionary and perlocutionary acts in the Sachsenspiegel.

Eike, “God left behind on earth two swords for the protection of Christianity.”[22] Eike’s statement is constative, either true or false; The Emperor’s statement in the Imperial Land Peace of Mainz, “We establish and decree by the power of our imperial authority and in conjunction with the loyal men of the realm (Dobozy 43) is strictly performative; it has no truth value; rather, it performs the action it describes, “we establish.” John Searle, after Austin but equally famously, has isolated five categories of illocutionary acts.

One act may simultaneously involve more than one category. We tell people how things are (Assertives), we try to get them to do things (Directives), we commit ourselves to doing things (Commissives), we express our feelings and attitudes (Expressives), and we bring about changes in the world (Declarations).[23]

Thus in the Landpeace, by “establishing and decreeing,” the emperor has made a Declaration. This is a Performative and performatives require certain conditions for them to work. The Landfrieden (Landpeace) actually becomes law because the appropriate conditions for the Performative to work are in place: an elected emperor, the support of loyal men of the realm. The effect is to institutionalize what he said. His words create institutional facts. If Eike had uttered the same words, they would have failed as a Performative expression; they would not have had the effect of creating a law because the appropriate conditions were not present.

The line between constatives and performatives blurs, however, when the performative verb (establish and decree) is not present, “I will meet you tomorrow” implies “I promise that . . .” so that it counts now as a performative. Thus Eike’s “God left behind two swords” becomes: “I assert that . . .”, and when he describes a law, custom, or judicial process, e.g. “People with diminished legal capacity have no wergeld” his utterance becomes the performative (“I assert that . . .”). [24] Eike’s (not so) silent voice registers a performative every time he describes, i.e. asserts to be the case, an established legal custom. There are scores upon scores of these throughout the text. It is out of this repetition that his concern about his authority emerges as a possibility.

Eike’s descriptions in their constative capacity are subject to the true or false test. As a practical matter, this could only be carried out by those of his contemporaries who were as familiar with the law as he. Some would have known that he was a Schöffe (an expert on legal matters) who sat alongside the judge in court proceedings, or they might have been impressed by his associates and patrons and so conceded his authority to speak. In fact, his primary audience most probably comprised those members of rural society. In this period before learned jurists were on the scene, they were the ones charged with administering and enforcing the law without the benefit of written statutes. In varying degree they would have been already familiar with at least some of the practices described in the law book and would bring their own (imperfect) memories of them to it. Eike’s performatives would fill in the gaps. And for the uninformed, they constitute virtually the entire law book.

And it is these performatives that tell the tale. They are virtually all assertions. That fact alone might be enough to subvert the “truth” of what he says about Saxon law. But we learn more when we take the illocutionary point together with the propositional content. It is what he asserts that tells the tale. Eike was not relying entirely on his reputation or his connections to secure the authority of his law book. Through the assertive illocutionary speech act he associates himself and his book to authority and authorities ranging from God, to secular rulers ancient and contemporary, and to the Bible. These will have been prompted, in part at least, by concerns for its reception. His ubiquitous appeals to authority throughout the text could be the consequence of an anxiety about the reception of the book. As the maker of a text, Eike is also in the construction business. When he recorded Saxon legal practices, he first produced a text which also and inevitably inscribed values, attitudes, prejudices, and biases of the essentially male, landed, knightly class which had retained him, and to which at some level he also belonged.

Their interests, and so his, were to legitimize and stabilize the past in a time of political uncertainty, and to preserve the legal culture by textualizing it, thereby freezing his account of legal tradition.[25] He elected to record this tradition in German prose, but in a famously rambling, freely-associating, unsystematic style further complicated by difficult syntax.[26] What is more, his writing is replete with subjective asides and commentary, references to the Bible, historical figures and events, and proverbial wisdom. Compared with the language of an official statute from about the same date, the Imperial Land Peace of Mainz (1235), unmistakably a Declaration, Eike’s inscription of Saxon customary law is buttressed by illocutionary Assertives identifying his authority to encode legal customs.[27]

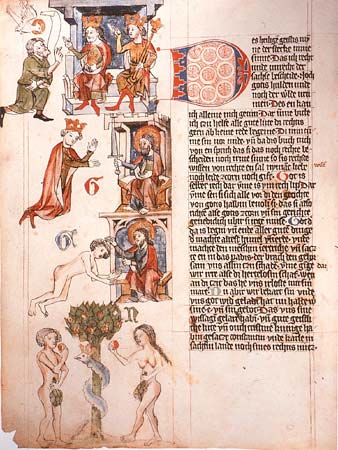

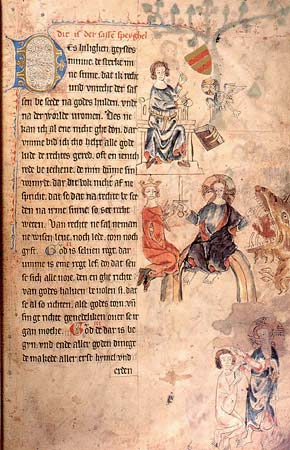

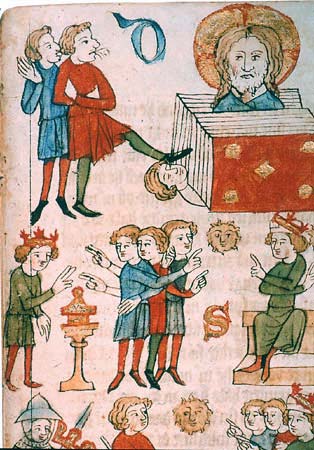

Two of the four prologues[28] to the Sachsenspiegel are attributed to Eike.[29] In the second prologue, he refers to divine law, [I assert that] “Got ist selber Recht” (God himself is the law), and then, following more Assertives, to the laws provided by the emperors Charlemagne and Constantine, and finally to Saxon law. This series of Assertives establishes a direct line from what he will be writing to imperial and then divine authority. Prologues survive in three of the illustrated recensions, with pictures that provide a kind of frontispiece. The first page of images relates to the most quoted phrase of the prologue: Gott ist selber Recht. Inspired by the Holy Spirit, Eike kneeling speaks and/or listens to Constantine and Charlemagne about the law yet to be inscribed on the empty banner. The inspiring Holy Spirit with nimbus hovers above the author (Figure 3). In the Oldenburg recension the pictorial image relating to the same text shows Eike, seated as author under the arms of the Counts of Oldenburg, pointing to a dove with nimbus (Holy Spirit), the source of his inspiration for the book in the lower foreground. Between them the arms of Oldenburg are repeated (Figure 4).

Fig. 3. Sachsenspiegel, ca. 1360-75, Wolffenbüttel, Herzog Augustiner Bibliothek, MS Cod. Guelf. 3.1 Aug. 2o f. 9v.

Fig. 4. Sachsenspiegel, 1336, Oldenburg, Der Landesbibliothek Oldenburg, MS Cim I 410, f. 6r.

As Eike brings his book to a close, he writes more confidently, or affects to do so, in the Lehensrecht (feudal law):

This book shall make many an enemy, for all those who strive against God and Law will be enraged because it pains them to see that the law is always revealed. (W Lnr. 85r)[30]

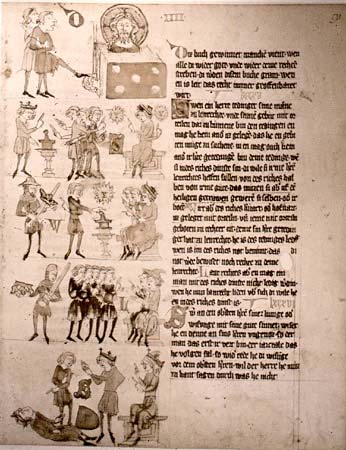

In the associated illustration in the Wolfenbüttel Codex in the top register of folio 85r (Figure 5), we see Eike under his book with closed eyes. Two men, distinguished by their dress as lowborn, kick and spit on the book from whose pages emerges a bust of God with nimbus. In the Dresden recension in the top register on folio 91r, (Figure 6). Eike under his book, with eyes closed and unpainted is represented as deceased.

Fig. 5. Sachsenspiegel, ca. 1360-75, Wolffenbüttel, Herzog Augustiner Bibliothek, MS Cod. Guelf. 3.1 Aug. 2o f.85r.

Fig. 6. Sachsenspiegel, ca. 1295-1363, Dresden, Der Sächsischen Landesbibliothek—Staats—Und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden, MS Dr. M32, f.91r.

The illustrators of the Dresden Codex (1295-1363) and the Wolfenbüttel (1348- 1362/71) come more than a century later than Eike’ s text.[31] The “God and Law” of this text has been collapsed into the “God is Law itself” of the Prologue. The enemies are represented as vulgar, ill-mannered boors and as such, unenlightened and unlettered, avoiding the idea that other types might be included among the book’s enemies. The contours of the noses may also reference Jews. Though Jews would not normally be represented as boors, the medieval representational code often condenses events, chronologies, and concepts in one depiction.[32] The illustrations for the prologue coupled with those of the enemies-of-the-book span Eike’s professional life. His closed eyes and unpainted head in the Dresden manuscript suggest a deceased Eike, with the law book standing as his gravestone. Coming as they do at the beginning and end of his book the illustrations act as bookends, shoring up his contribution to the life of the law in Medieval Saxony and work beyond the illocutionary force of his words to confirm and enhance his and his book’s authority.

In May 2006 at the 41st International Congress on Medieval Studies held at Western Michigan University there were five sessions (approximately 15 to 20 papers) devoted to Madeline Caviness’s Triangulation theory and recent scholarship. My contribution (revised here) was twofold: to place her Triangle theory in a historical context and then, by following her advice concerning the use of post-modern speech act theory, to “produce a new historical truth” – in this case Eike’s anxiety about his authority to write the law book, an anxiety represented by the high number and types of Assertives. I intended my essay to emphasize theoretical matters which accounts for a minimum number of examples of Eike’s Assertives in the speech act theory analysis. The major point is to demonstrate the theory and critical value of Caviness Triangulation.

Charles G. Nelson’s training in Austria and Germany grounded him in historical linguistics and medieval German dialects and literature: he studied Middle High German language and literature in Innsbruck, Austria, with Karl Kurt Klein, Old High German and Gothic in Germany with Ingo Reiffenstein and Emil Ploss. After earning his doctorate in German Language and Literature with the GI Bill at the University of Michigan he served on the faculty, and for a period as Dean of the Graduate Schools, at Tufts University, where he was Professor Emeritus. He taught literary theory beginning in the 1960s and systematically tested its relevance to medieval writing and culture in numerous case studies presented at scholarly meetings and in articles, most recently concerning Hrotsvit von Gandersheim, the Nibelungenlied and the Sachsenspiegel. He was at pains to represent the relevance of medieval studies to his students and peers through analyses of medieval texts, keeping pace as he proceeded with fresh theoretical insights as they evolved. Since the 1980s he taught multi-disciplinary courses and conducted research with Madeline Caviness, with a focus on gender theory and feminism.

Charles Nelson died in Massachusetts in September of 2008 after a lengthy illness.

References

| ↑1 | A revised version of a paper presented at the 41st International Congress on Medieval Studies at Kalamazoo, Michigan in May, 2006 in one of five sessions devoted to the approach to the study of medieval art objects first proposed in: Madeline H. Caviness, “The Feminist Project: Pressuring the Medieval Object,” Frauen Kunst Wissenschaft 24 (1997): 13-21. I cite p. 14 at the beginning of the paper. Aspects of the argument and supporting evidence appear in different contexts in earlier publications and conference papers. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Madeline Caviness tells me she did not know this model, so she was not consciously adapting it to formulate her triangle, not surprising since it has long since lost any relativity to current critical practice. My point in reintroducing it is simply to underscore the passive remoteness from the texts of the Abrams critic versus the active engagement of the Caviness historian/viewer/interpreter. See Caviness, “The Feminist Project,” 14-15. |

| ↑3 | Roland Barthes, Image Music Text, trans. S. Heath (New York: Hill and Wang, 1977), 155-164. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-03518-2 |

| ↑4 | For an early and itself historically interesting account of their work and significance, see William Elton, A Guide to the New Criticism (Chicago: The Modern Poetry Association, 1953); Allen Tate, On the Limits of Poetry: Selected Essays: 1928-1948 (New York: Swallow Press, 1948) ; John Crowe Ransom, The New Criticism (Norfolk, C.T.: New Directions, 1941) ; Cleanth Brooks, The Well Wrought Urn: Studies in the Structure of Poetry (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1947);R.P. Blackmur, Language as Gesture: Essays in Poetry (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1952). |

| ↑5 | Carolyn Porter, “Are We Being Historical Yet?” South Atlantic Quarterly 87, no. 4 (1988): 743-86, here 749. https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-87-4-743 |

| ↑6 | Madeline H. Caviness, “Patron or Matron: A Capetian Bride and a Vade Mecum for Her Marriage Bed,” in Studying Medieval Women, ed. Nancy Partner (Cambridge, M.A.: Medieval Academy of America, 1993), 31-60. https://doi.org/10.2307/2864556 |

| ↑7 | Caviness, “The Feminist Project,” 13-21. |

| ↑8 | Jane Flax, Thinking Fragments: Psychoanalysis, Feminism, and Postmodernism in the Contemporary West (San Francisco: University of California Press, 1990), 4. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520329409 |

| ↑9 | Ibid, 30-31. |

| ↑10 | Caviness, “The Feminist Project,” 14. |

| ↑11 | David A. Muldoon, “Reading Medieval Germany: The Sonderweg and Other Myths” (paper presented at the 81st annual meeting for the Medieval Academy of America, Boston, Massachusetts, 2006). |

| ↑12 | “The Mirror of the Saxons Shall

this book be called. For from it Saxons will come to know their law As well as a woman knows her countenance in a mirror.” The name of the Sachsenspiegel or Saxon Mirror comes from the passage cited above, in the rhymed preface attributed to Eike. My remarks on the Sachsenspiegel and its author, Eike von Repgow are generally based on shared research with Madeline Caviness which accounts for the use of the pronoun “we.” |

| ↑13 | Heiner Lück, Über den Sachsenspiegel: Entstehung, Inhalt und Wirkung des Rechtbuches (Halle an der Saale: Janos Stekovics, 1999). See also the second edition with an article on the counts of Falkenstein during the Middle Ages by Joachim Schymalla (Dössel: Verlag Janos Stekovics, 2005). |

| ↑14 | Ulrich-Dieter Oppitz, Deutsche Rechtsbücher des Mittelalters, Beschreibung der Rechtsbücher, vol. 1 (Böhlau: Cologne and Vienna, 1990-1992). |

| ↑15 | Karl von Amira, ed., Die Dresdner Bilderhandschrift des Sachsenspiegels, vol. 1 (Leipzig: Karl W. Hiersemann Verlag, 1902) ; Walter Koschorreck, Der Sachsenspiegel. Die Heidelberger Bilderhandschrift Cod.Pal.Germ. 164 (Frankfurt-am- Main: Insel Verlag, 1989) ; Eike Von Repgow, Sachsenspiegel. Die Wolfenbütteler Bilderhandschrift Cod. Guelf. 3.1 Aug. 2. Faksimile, ed. Ruth Schmidt-Wiegand, 3 vols. (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1993) ; Ruth Schmidt-Wiegand, ed., Der Oldenburger Sachsenspiegel: Vollständige Faksimile-Ausgabe im Originalformat des Codex Picturatus Oldenburgensis Cim I 410 der Landesbibliothek Oldenburg, vol. 1, 3 vols. (Graz: Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt, 1995) ; Heiner Lück, ed., Vollständige Faksimile-Ausgabe im Originalformat des Dresdener Sachsenspiegels: Mscr. Dresd. M32 der Sächsischen Landesbibliothek–Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden, vol. 107 (Graz: Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt, 2002). |

| ↑16 | The earliest being Notker III from St. Gallen. See Burghart Wachinger, ed., Deutschsprachige Literatur des Mittelalters: Studienauswahl aus dem ‘Verfasserlexikon’ (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2001), col. 612-638. |

| ↑17 | We were able to meet with Ruth Schmidt-Wiegand at her research center, Sonderforschungsbereich 231 in Münster before it closed, and are grateful for her questions, assistance and comments. In addition, during the summer of 1998 we were privileged to examine the original manuscripts, with the help of conservators and curators. We are especially grateful to Dr. Armin Schlechter, Leiter der Abteilung Handschriften und Alte Drucke of the Heidelberg Staatsbibliothek, and to Michael Stanske of the Handschriftenabteilung. Also Dag-Ernst Petersen who arranged to let us see the water- damaged leaves from the Dresden recension, that he had just consolidated, next to the Wolfenbüttel recension, and finally Dr. Egbert Koolmann of the Niedersächsiche Sparkassenstiftung who supervised our examination of the Oldenburg recension. |

| ↑18 | As assuming as that might sound, since the advent of theory in the 1960s virtually none of the scholarship on the Sachsenspiegel from any field takes into account its significance for the historical disciplines. This obviously by no means detracts from the indispensability of its contributions. Especially for our project, consider the work of the editors of the facsimile volumes: Walter Koschorreck, Ruth Schmidt-Wiegand, and Heiner Lück. |

| ↑19 | Seminal work still continues, as in a recent article by Peter Landau on the position of Eike as a European jurist, on the connection of the Sachsenspiegel to learned law, and on the place of Altzelle in the history of European law: Peter Landau, “Eike Von Repgow, Altzelle und die anglo-normannische Kanonistik. André Gouron D.D.D.,” in Deutscher Rechtshistorikertag (Bonn: Leopold-Wenger-Institut für Rechtsgeschichte, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Munich, 2004): 73-101. |

| ↑20 | On the appropriateness of applying the discourses of non-literary fields in literary criticism see the brief and brilliant exposition by Jonathan Culler: Jonathan Culler, Literary Theory: A Very Short Introduction, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997). He also gives a very clear Assessment of speech act theory, pp. 94-107. |

| ↑21 | J. L. Austin, How to do Things with Words, 2d ed (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 1962). |

| ↑22 | Maria Dobozy, trans., The Saxon Mirror: A Sachsenspiegel of the Fourteenth Century (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999). |

| ↑23 | John Searle, Expression and Meaning: Studies in the Meaning of Speech Acts (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979), 12-20. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511609213 |

| ↑24 | Wergeld is the amount of money, based on status, which was paid to the family of the victim of a homicide by the murderer, or the murderer’s kindred. |

| ↑25 | The consensus is that customary law was undergoing rapid change. See Karl Kroeschell, Deutsche Rechtsgeschichte (bis 1250) (Reinbeck: Rowohle Taschenbuch Verlag, 1972), 315-316; and Rolf Lieberwirth, “Eike Von Repgow Und Sein Sachsenspiegel: Entstehung, Inhalt, Bedeutung,” Veröffentlichungen der Kölner Museen (1980): 34. |

| ↑26 | See Maria Dobozy’s remarks on Eike’s style in Dobozy, 37 |

| ↑27 | Dobozy, 43-49, whose translation of the Land Peace is devoid of any editorializing. See Schmidt-Wiegand’s analysis of several aspects of Eike’s style in Ruth Schmidt-Wiegand, “Sprache und Stil der Wolfenbütteler Bilderhandschrift,” in Die Wolfenbütteler Bilderhandschrift des Sachsenspiegels: Aufsätze und Untersuchungen. Kommentarband zur Faksimile- Ausgabe, ed. Ruth Schmidt-Wiegand, vol. 3 (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1993), 201-218, esp. 207-08 on the similarity with the spoken language. The correspondences she finds with the Land Peace of Mainz are limited to the phonological level. Yueguo Gu, in an article calling for a reassessment of perlocution notes in passing that statements perceived as coming from influence and power will accepted as true. Yueguo Gu, “The Impasse of Perlocution,” in Humanities: Chinese Academy of Social Sciences Forum, ed. L. Chengzhong and S. Jinjian (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1999), 171-201, here 177. |

| ↑28 | One of them is called the “Rhymed Preface” (Reimvorrede). Prefatory remarks by medieval authors regularly and sometimes extravagantly cite sources and patrons. Here Eike gives credit to his patron Hoyer von Falkenstein for persuading him to translate his (Eike’s) own Latin Sachsenspiegel into German to make it available presumably to practitioners involved in the administration of Saxon law. But this leaves him without a traditional source text, because the Latin one invoked is also by Eike. We contend that his ubiquitous appeals to authority throughout the text could be the consequence of an anxiety about the reception of the book. |

| ↑29 | Lück, Uber den Sachsenspiegel, 24: “Zunächst sei noch einmal hervorgehoben, daß der Sachsenspiegel eine private Rechtsaufzeichnung ist und niemals durch eine herrschaftliche Autorität ausdrücklich als geltendes Recht in Kraft gesetzt wurde. Im Wege der Rechtsanwendung durch die Gerichte, Herrschaftsträger, und die bäuerliche Bewölkerung erlangte er dennoch eine große Autorität.” Let me emphasize once more that the Sachsenspiegel is a private law book and was never legalized. Nevertheless it assumed significant authority from its use by the courts, (local) authorities, and the rural population. |

| ↑30 | Dobozy, 178. |

| ↑31 | Ruth Schmidt-Wiegand, ed., Die Oldenburger Bilderhandschrift des Sachsenspiegels, vol. 50 (Berlin: Kulturstiftung der Länder, Bundesministerium des Innern, 1993). |

| ↑32 | Karl von Amira on page 25 of his introduction to the 1902 facsimile of Dresden (fn.4 above) notes that, when the drawing is carefully done, the bent nose of Jews is evident. |