Asa Simon Mittman • California State University, Chico

Susan M. Kim • Illinois State University

Recommended citation: Asa Simon Mittman and Susan M. Kim, “Anglo-Saxon Frames of Reference: Framing the Real in the Wonders of the East,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 2 (2010): https://doi.org/10.61302/LNHO7205.

“The picture is only partly framed in”[1]: Framing the Images

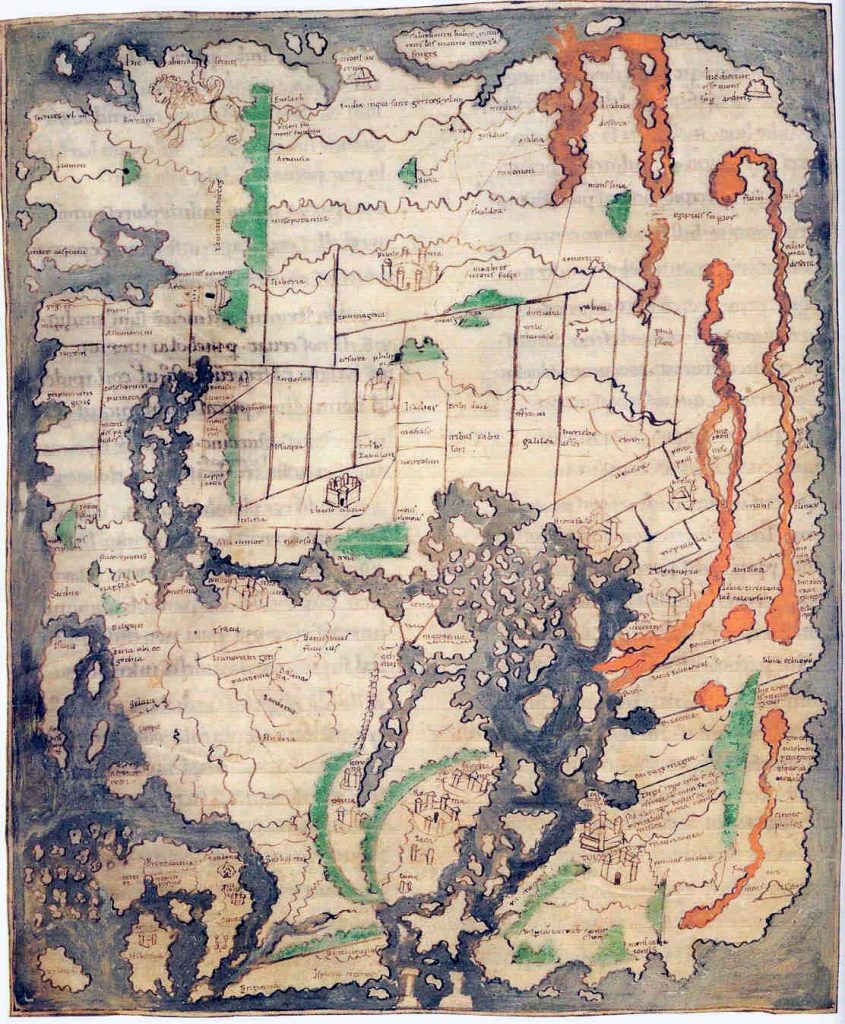

The frame was without question a vital element of manuscript decoration in Anglo-Saxon England. Indeed, looking at products of the Winchester School, we see that frames can be the dominant element of a folio.[2] As in the Benedictional of Æthelwold, this style allows explosively foliate frames to overwhelm their contents.[3] In more subtle examples, we can see the importance of framing in medieval geographic representations, which are inherently and often explicitly connected to what will form our focus, here: the illustrated Wonders of the East in the Beowulf Manuscript (London, British Library, Cotton Vitellius A.xv).[4] In the Cotton Map, bound with a later copy of the Marvels of the East, we find frames within frames, such that if we consider the sea as a naturalistic frame for the ecumene, “the map circumscribes the earth with a grey wash of ocean that in effect presents a third frame inside the double-lined border and then the margins of the manuscript page” (Figure 1).[5] The world is framed and reframed, filled with borderlines in the interior and surrounded by multiple demarcations around its exterior. In the Wonders, by contrast, both visual and textual framing devices are consistently represented as partial, allowing for interpenetration of text and image, for example, or absorbed into the images themselves. That is, framing in the Wonders is as decisively emphasized as it is in the mappaemundi, but in the Wonders, the frame speaks not its capacity to contain, separate, and render knowable, but rather the fiction of such a capacity, and the inevitable porousness of the categories by which we apprehend the world.

Fig. 1. Cotton (Anglo-Saxon) World Map, London, British Library, Cotton Tiberius B.V, fol. 56v (© British Library Board, All Rights Reserved)

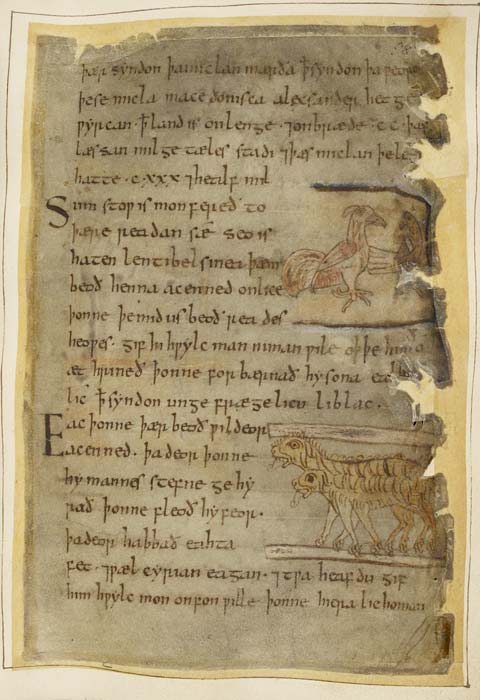

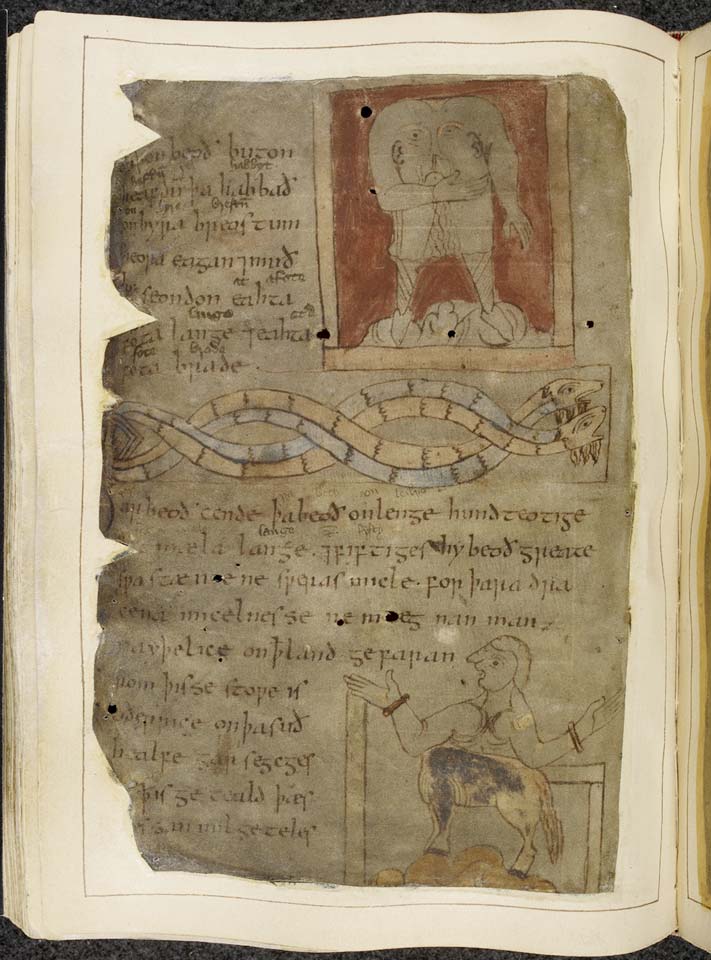

Fig. 2. Burning Hens; Inconceivable Beasts, London, British Library, Cotton Vitellius A.xv, fol. 2r [99r] (© British Library Board, All Rights Reserved)

Emmanuel Kant condemns ornamental elements in images that are “introduced like a gold frame merely to win approval for the picture by means of its charm—it is then called finery and takes away from the genuine beauty.”[6] The frames in the Wonders could not be accused of striving to charm the viewer, as these frames are not on the whole objects of great beauty, like those common to Baroque paintings, or even to manuscripts of the Winchester School,[7] for example. We might, though, invert this critique of beauty, as we reexamine the Wonders, these remarkable works of horror and outright ugliness. If a beautiful frame around a beautiful image might act as a distraction from genuine beauty, what of an ugly frame, such as (nearly) encloses the Burning Hens, arguably an ugly image (Figure 2)? This is an opened and incomplete frame around a monstrous image, as in harmony with it as a lovely frame around a lovely image, and just as potentially distracting. But the frames that Kant imagines are providing a window or door opening onto a fictive space beyond. They therefore distract from the image, as they are not part of it, not part of the imaginary world within. Nicolas Poussin, the Neoclassical painter, argued for the vital nature of the frame in a letter to his patron Chantelou, accompanying a recently finished work:

When you receive [your painting], I beg you, if you find it good, to decorate it with a little cornice, because it needs it, so that, by considering it in all its parts, the rays of the eye are retained and not scattered on the outside by other kinds of nearby objects which, occurring pell-mell with the depicted things, confuse the light.[8]

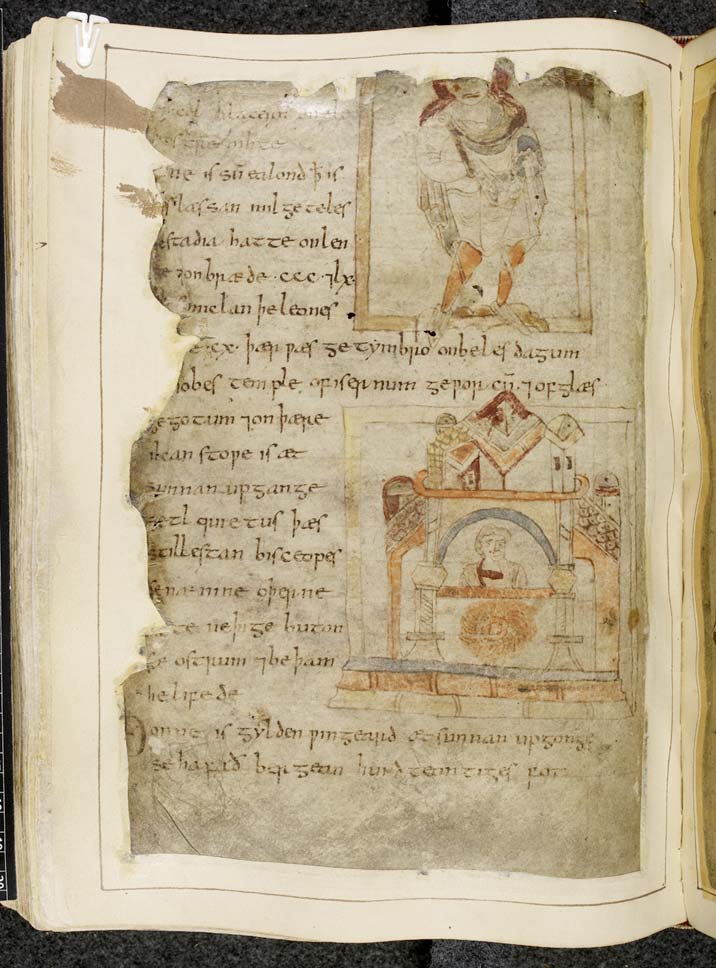

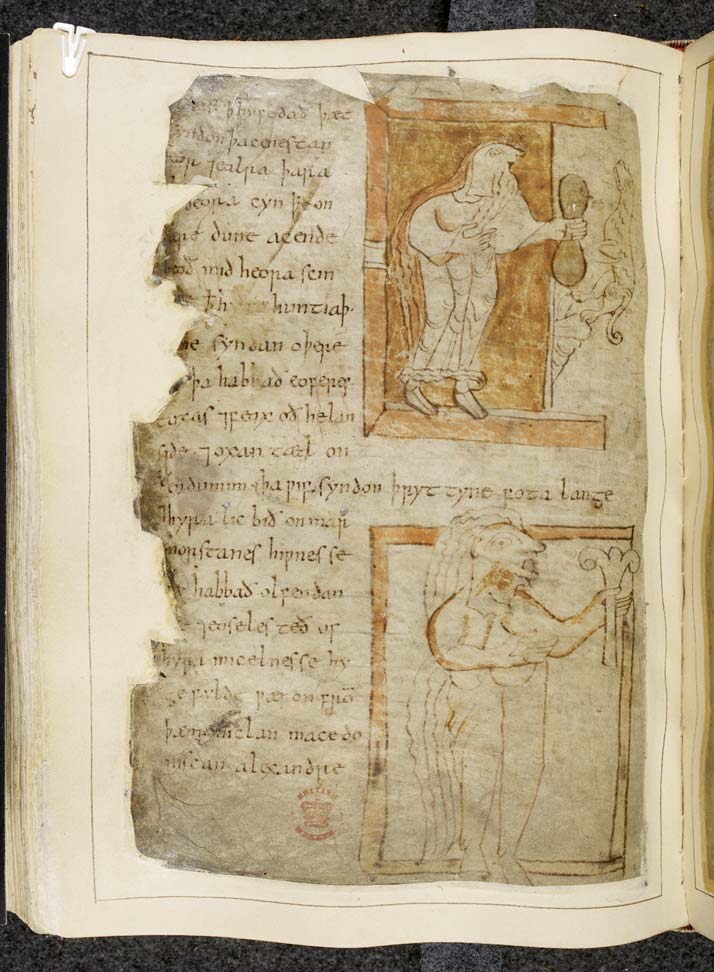

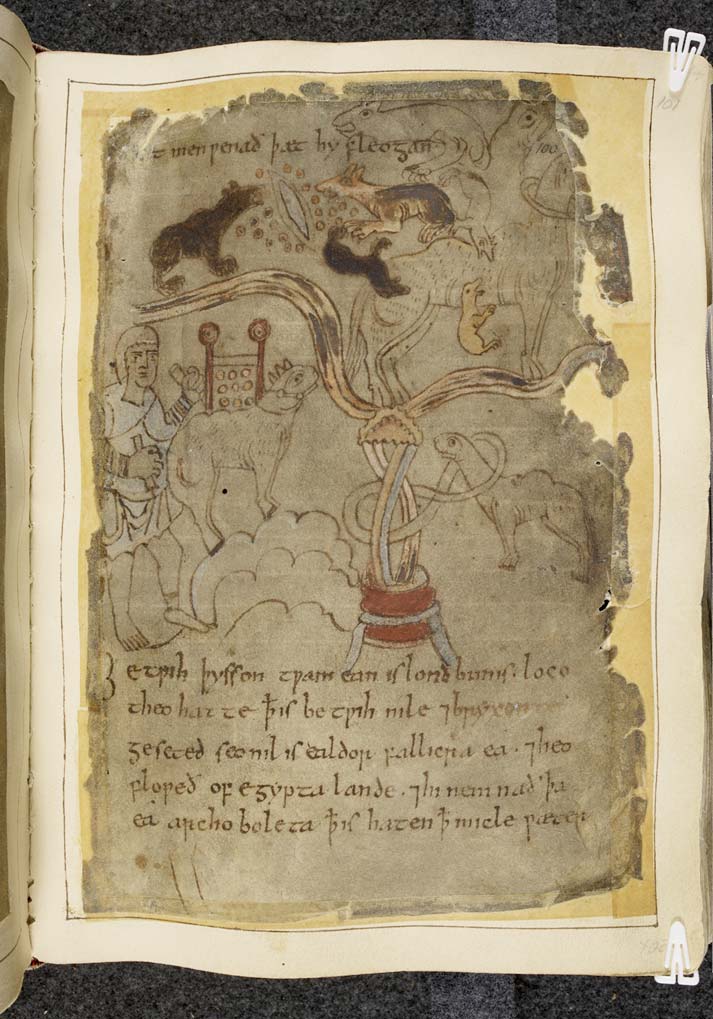

For Poussin, the frame provides a necessary focus for the painting within. The frames of the Wonders, by contrast, may be vital to the images not because they allow for containment of the images, retention of the “rays of the eye,” but because they are part of the images, not separate from them. Figures like the Donestre and the People Whose Eyes Shine Brightly (Figure 3) stand on their frames, while others like the Sigelwara and Boar-Tusked Woman (Figure 4) stand in front of them. Still others, like the Onocentaur (Figure 5) and Bearded Huntress (Figure 4), break through their frames. Some of the images even seem to incorporate them as part of their content, itself, as in the image of Quietus (Figure 3), “the most gentle Bishop,” where the lower edge of the frame also seems to be part of the architecture within the image. This lower edge is, then, both the frame and its contents. It is in this sort of slippage that the frames of the Wonders most notably fail and succeed. They fail to contain the threats within, and thereby collapse the distance that ought to exist between Anglo-Saxon reader-viewer and eastern wonder. In doing so, though, they succeed far more powerfully than is common in their later descendents, the two illustrated Marvels of the East manuscripts, the Psalter Map,[9] and elsewhere, by revealing a present threat, raw and unrestrained, transgressing the boundary between their world and ours.

Fig. 3. People Whose Eyes Shine Brightly; Quietus, London, British Library, Cotton Vitellius A.xv, fol. 7v [104v] (© British Library Board, All Rights Reserved)

Fig. 4. Bearded Huntress; Boar-Tusked Woman, London, British Library, Cotton Vitellius A.xv, fol. 8v [105v] (© British Library Board, All Rights Reserved)

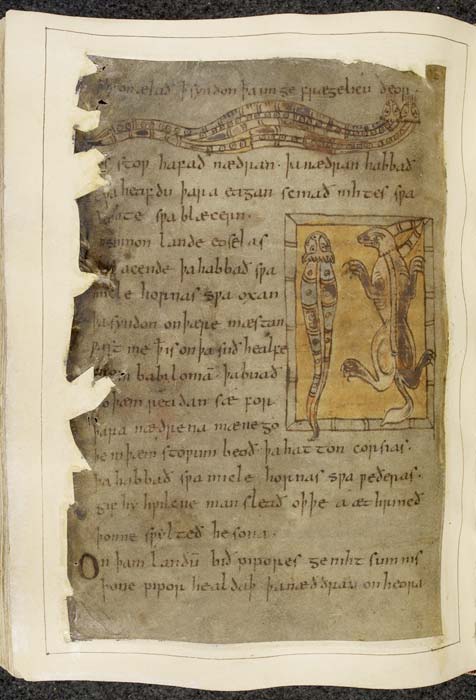

Fig. 5. Blemmye; Giant Serpents; Onocentaur, London, British Library, Cotton Vitellius A.xv, fol. 5v [102v] (© British Library Board, All Rights Reserved)

As Meyer Schapiro writes of insular images, content and its frame often contain elements that echo one another.[10] Owing to this correspondence, the figure and frame seem to be made of the same matter. One could compare this echoing to that of the frame around and image of the Corsias, the pepper- guarding serpents with shining eyes of the Wonders (Figure 6). The double-barred, curved bands marking the frame—unique in the manuscript—echo very closely the double-barred curves marking the serpent’s back. These same forms again appear in the horns of the Asses with Horns as Big as Oxen’s, housed in the same frame, so that all three elements of the image are in accord with one another.

Still, for Jacques Derrida and Craig Owens, while framing might be effective, its power is inherently harmful: “The violence of framing proliferates. It confines the theory of aesthetics within a theory of the beautiful, the theory of the beautiful within a theory of taste, and the theory of taste within a theory of judgment.”[11] The Wonders, by contrast, is ugly; it is troubling and dark and distorted, aesthetics which have, as well, framing processes. The violence of framing, generically speaking, is the segregation of this from that, one from the other. The breakdown of frames is also, though, a form of violence; it allows the meeting of parties that are often hostile to one another. The breakdown of the frame thus violates an idea of the integrity of the space of the image, and with it the separate space of the text, and the separate spaces of the viewer/reader. At the same time, the breakdown thus also facilitates the potential violence of contact between text and image, or image and viewer, contacts the Wonders explicitly promises can result in destruction of one or the other, or both. Text and image are much more typically segregated within their own protective boxes, as in both later Wonders manuscripts, whereas here, they are allowed to conflict openly. This is most clearly the case with the Ant-Dogs (Figure 7), which lack any frame and actively confront their text as if to stop it from “fleeing,” with one Ant- Dog wrapped around the word fleogan, as if by doing so it could keep the text, and the man to which it refers, from flying away.[12] This conflict or contact between text and image appears elsewhere. We find similar interaction between the image and text of the two-headed serpents that lick or breathe flames on deor (wild beast) and those of the Onocentaur-Homodubii (Figure 5), whose open hand extends between the incomplete frame and the text as he gestures at or seems to be speaking the word, gefaran (to travel, to go, to proceed). Here, bursting from the broken frame, he seems to be challenging the statement made by the text, that “no person can easily travel in that land,”[13] since he seems on the brink of bursting out of his inadequate containment, traveling not only “in that land,” but also into the space of the text and into the space of the reader.

Fig. 6. Two-Headed Snakes; Corisas, London, British Library, Cotton Vitellius A.xv, fol. 2v [99v] (© British Library Board, All Rights Reserved)

Fig. 7. Ant-Dogs, London, British Library, Cotton Vitellius A.xv, fol. 4r [101r] (© British Library Board, All Rights Reserved)

“Pointing marks separation”[14]: Framing the Text

Although we thus far have focused on framing with respect to the images, and to the relationship between image and text, we wish to argue that the Wonders concerns itself as well with questions of framing within the text, questions articulated through the orthographic conventions of pointing, capitalization, and spacing, but also through internal repetitions, such as the striking repetition of distances.

The episodic narrative is broken into descriptions of creatures and places most often marked by an enlarged initial capital or framed by statement of the distance, in two different units of measurement, of the particular wonder from the wonder that preceded it. The Wonders begins, for example,

Seo landbuend on fruman from antimolime pæm lande pæs landes is on gerime pæs læssan milgetæles pe studio hatte fif hund 7 pæs miclan pe leones hatte preo hund 7 eahta 7 lx. On pæm ealande bid micel mænegeo sceapa 7 ponon is to babilonian pæs læssan milgetæles stadio hundteontig 7 eahta 7 lx 7 pæs miclan milgetæles pe leones hatte fifyne 7 hund teontig.[15]

(That colony is five hundred of the smaller miles, which are called stadia, and three hundred and sixty eight of the greater, which are called leagues, away from Antimolima. On that island there is a great host of sheep. And it is a hundred and sixty eight of the lesser miles, stadia, and a hundred and fifteen of the greater miles called leagues from there to Babylonia.)

Certainly, the nearly obsessive measurement of distance in the Wonders and the insistent iteration of geographical nomenclature emphasize the importance of the sense of place, of realizable location to the significance of the wonders presented. The difference in discourse—calculation versus description— is further emphasized both by the use of roman numerals and by the copious pointing which separates roman numerals from text. As Kemp Malone notes, “In our codex, as elsewhere, pointing marks separation. The scribe might punctuate if he wished to separate one word or word-group from another, or from its context, by a visible sign.”[16] This separation clearly establishes a kind of frame for the different discourse of the description. But of course at the same time, this overwhelming detail effectively dislocates the creature it frames: the multitude of sheep is lost in the proliferation of numbers, units, and repeated formulae. And, to compound matters, one need not even complete the calculation to know that 500 is not to 368 as 168 is to 115 (1 to .736 and 1 to .684).

One might argue that the emphasis is merely on the distance from the viewer: the wonders must be there, and what is necessarily emphatic and precise is not the actual distance but the fact that the particular wonder is and that it is not here. Hence, if we examine the statements, emphasized by initial capitals extending into the margins, which also serve to introduce most of the wonders, it is not surprising to find the iteration of forms of on Jæm landum (once), Dær beoa (five times), and on summon lande, or related phrases, (no less than six times): the wonders are in a certain land, that land, there.

But these repetitive framing statements also suggest that at least important as “thereness” to the representation of the wonders is the insistence on sequence: by far the most frequent formula—it occurs nine times, six of which occur in sequence—begins, Donne is. . . (Then, there is . . .) In this pervasive emphasis on sequence, we hope to suggest a function for the proliferation of contradictory statements on the measurement of distance.

To begin with, in our own response to these statements we confess to a degree of embeddedness in a contemporary context in which scholars in the humanities may sometimes encounter numbers simply as incomprehensibility— those parts of the text that refer to other kinds of knowing, which necessarily lack literary meaning. But of course these strikingly reiterated formulae and strange calculations in the early medieval context make explicit connection to the more generically literary questions, in the contemporary context, raised by the text: questions, for example, about how we know things, about how we represent them, and about what in this knowing and representation makes us human. As Isidore of Seville articulates for the early medieval context:

Through numbers, we are provided with the means to avoid confusion. Remove numbers from all things, and everything perishes. Take away the computation of time, and blind ignorance embraces all things: those who are ignorant of the methods of calculation cannot be differentiated from the other animals.[17]

Isidore concludes this passage on “Quid praestent numeri” by noting, “those who are ignorant of the methods of calculation cannot be differentiated from the other animals.”[18] In the context of the Wonders, with its dog-headed Cynocephali, its Boar-Tusked Women, its Centaurs and the hybrid Donestre, Isidore’s criticism seems particularly apt. These beings hardly can be differentiated from the “other” animals, and more significantly, cannot often be fully differentiated from their human viewers and readers.[19] The profuse but also contradictory numbers create a sense of collapsing distances, bringing there ever closer to here, just as the human element within and among the wonders renders them as us.

However, Isidore, through the shared property of sequence, also links numbers and calculation to the powers of the language, to the letter itself: in addition to nomen, figura, and potestas, Isidore notes that sequentia may also be considered as a property of the letter:

There are three things associated with each letter: its name, how it is called; its shape, by which character it is designated; and its function, whether it is taken as vocalic or consonantal. Some people also add ‘order,’ that is, what does it precede and what does it follow, as A is first and B following…[20]

We would like to suggest here, then, that what we have been tempted to read as the merely dislocating and disorienting function of the numbers and formulae may also articulate an understanding of place, not as a matter of geography, or even experience, but as a matter of text; but also that the very grounds for framing the description, separated out as another discourse, another way of knowing within the text, reasserts its contiguity with that which it “frames”: the iteration of number also emphasizes both the necessity for difference within language and the function of text as sequence.[21] That is, framing within the text evokes exactly the problematic of the framing of image by text, or of image by a visual frame.

“The simulacrum is true”: Framing the “Real”

Jean Baudrillard opens his discussion of Simulacra and Simulation with a quotation from the Book of Ecclesiastes: “The simulacrum is never what hides the truth—it is truth that hides the fact that there is none. The simulacrum is true.”[22] If we consider the wonders as simulacra, we can also suggest that it does not hide “real” beings. Rather, the wonders are, themselves, their own truth, their own reality. But, of course, Baudrillard’s quotation from Ecclesiastes is not really a biblical quotation but a demonstration of the principle of the simulacrum. Despite not being “real,” this epigraph serves precisely the same function it would if it were: it prepares the reader for what is to come and, like the many false attributions of the Middle Ages—all the Pseudo-Augustines and Pseudo-Jeromes and the like—lends the argument which follows a certain authority. In this case, the false attribution turns the quotation into a simulacrum, in which the copy has no original.[23]

The simulacrum or simulation, as opposed to the “fake,” has for Baudrillard qualities of the “real,” so it cannot be treated simply as real or as not real.[24] The Wonders function similarly, as they are (for the most part) totally artificial (in the sense of imaginary) and yet can simultaneously function as if they were real. Further, following Baudrillard, these simulations undercut the reality of the actual real: the Wonders thus contains the power to make the tangible world of Anglo-Saxons not reassuringly more tangible, but threateningly less real. One of Baudrillard’s case examples forms a good parallel for the Wonders. Baudrillard describes the Tasaday, a stone-age, indigenous Philippine tribe purportedly cut off from rest of world for 800 years, until they were “discovered” by Manuel Elizalde, Jr. After the encounter, the Tasaday were sent back to a region surrounded by virgin forest, apparently to protect and preserve their ancient ways. In Baudrillard’s analysis, the Tasaday have to be returned to the forest, so that the practice of Ethnology can continue. The discipline relinquishes this one group so that the enterprise, the “reality principle” might continue.[25] Of course, though, the Tasaday were not the perfectly isolated tribe they first seemed to be, and so they serve as a doubled example.[26] As Stuart Kirsch writes, “the current anthropological consensus regarding the Tasaday is that they were a group that separated from their neighbors and lived in relative poverty and isolation until several Filipino politicians sought to take advantage of the situation.”[27] That is, the Tasaday had to be removed from the anthropological world in order that they continue to exist as isolated—although they never were, it seems, isolated to begin with. We argue that, in a kind of parallel, the existence, the reality principle of the Wonders likewise relies entirely on their total inaccessibility. Although many episodes within the Wonders involve contact between the wonders and visitors, such contact is almost always represented as extremely dangerous: wonders burn up completely themselves or those who touch them, or otherwise wholly or partially consume their visitors.[28] This promise of danger resulting from contact with the wonders reiterates the premise that the continued “reality” of the wonders was predicated on the assumption that no Anglo-Saxon would travel to their homelands in “the East” to confirm or disprove their existence.

Still, we need not rely on modern theorists to come to an understanding of how the “real” might function in the Middle Ages. Anselm’s writings give us a sense of how what we might reflexively think of as ‘real’ was, for the Anglo- Saxons, anything but ‘real.’ As Martin Foys writes, “in Anselm’s view, the highest form of reality is divine, and therefore timeless and spaceless … What is real is a representation, and what is represented can lead to a higher reality.”[29] The tangible world was for the Anglo-Saxons, as for many medieval groups, a sign of God’s intent, provided to be examined for the greater truths it could reveal. As Augustine writes, “the circle of the earth is our great book. In it I read the perfection which is promised in the book of God.”[30] If the earth is not a reality (or not merely a reality) but rather, a book (and if this, in turn, renders it of greater use, in that it can be used to guide a contemplator towards salvation), then in turn, a book can constitute a more significant form of reality than the world in which it is contained, as a source through which to gain an understanding of God’s divine plan.

The wild fantasy presented by the Wonders, then, can be viewed in light of Anglo-Saxon notions about what constituted more significant realities than the merely tangible and observed. Indeed, it was that which remained unseen that formed the core of medieval aspirations and fear: Jerusalem, heaven and God, demons, hell and Satan. Certainly, nothing was more real in the medieval worldview than what we might interpret as unseen intangibles.

But how do we divide off the “real” from the imaginary? Henry Heydenryk writes that such a solid device as a literal frame is necessary because “a transition must be made from the imaginary world of the image to the real world of the wall,”[31] but in the case of the Wonders, the images do not present a fictive space within the frames. The figures, like their painted images, are directly present on the surface of the vellum. In his Landscape into Art, Kenneth Clark writes that Antonio del Pollaiuolo’s Martyrdom of St. Sebastian presents “a landscape of astonishing sweep and truth.”[32] But as representation, this landscape can only represent “truth” through illusion. Truth in painting is, at least for many modern artists and their critics, the surface of the work, and illusion is falsehood. Clement Greenburg argues with respect to “nonobjective art,” for example: “The avant-garde poet or artist tries in effect to imitate God by creating something valid solely on its own terms, in the way nature itself is valid, in the way a landscape—not its picture—is aesthetically valid; something given, increate, independent of meanings, similars or originals.”[33] Herbert Kessler opens his study, Seeing Medieval Art in strikingly similar terms:

Overt materiality is a distinguishing characteristic of medieval art. In most works, the substances used to fashion figures and ornament are apparent in ways that, say, the oil paint on a fifteenth-century Flemish panel or the marble of a Neo-classical sculpture are not. The materials do not vanish from sight through the mimicking of the perception of other things; to the contrary, their very physicality asserts the essential artifice of the image or object. Such typically medieval media as mosaic, stained glass, and enamel all demonstrate this point.[34]

The images of the Wonders have a truth to them: in their insistence at once on their materiality and their artifice, their function not only as sign but also as simulacrum, they are what they are; they exist and they exist not simply as images of something else.

The wonders dwell in a fittingly marginal zone, very similar to that of the mappaemundi, “occupying an uneasy liminal space between representation and reality, at least in part constructing the world they seek to represent.”[35] While the maps have a theoretically “real” basis (the actual world) and many of the wonders do not, as a mere sign of God’s plan, as a lesser reality when compared with the greater truth of the divine, the “real world” we all know was, in the end, no more real than the wild fantasies of the Wonders. But while the mappaemundi frame and reframe the image of the world, the world of the Wonders, in this manuscript, like the image of its burning hens, is only ever partly framed, and hence is only ever “partly framed in.”[36] That is, the Wonders allows for at least potential contact between its partially framed images and texts and those worlds other frames might close off to them. In this contact we read the potential for a revision of other fictions of separation—of the human from the animal, the east from the west, the image from the text, the image/text from the “reality”—by which we cannot help but know them.

References

| ↑1 | The Nowell Codex: British Museum Cotton Vitellius A.xv, Second MS, ed. Kemp Malone (Copenhagen: Rosenkilde and Bagger, 1963), 117 (description of cock and hen [2R]). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Elzbieta Temple (A Survey of Manuscripts Illuminated in the British Isles: Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts 900-1066 [London: Harvey Miller, 1976], 17-19) discusses the ‘Winchester School,’ which was by no means confined to Winchester. The style, as Temple notes, is characterized by “exuberant frame decoration” (p. 18). See also T. A. Heslop and V. Sekules, Medieval Art and Architecture at Winchester Cathedral (British Archaeological Association Conference Transactions 6) (London: British Archaeological Association,1983); and Francis Wormald, “The ‘Winchester School’ before St. Aethelwold,” in England Before the Conquest, ed. Peter Clemoes and Kathleen Hughes (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1971), 305-13. |

| ↑3 | London, British Library, Add. MS 49598, Winchester (Old Minster), ca. 971-84. See Temple, Anglo- Saxon Manuscripts, 49-53, no. 23; and the color facsimile: Andrew Prescott, The Benedictional of St Aethelwold (London: British Library, 2002). |

| ↑4 | For dating and provenance, see the following: Andy Orchard follows David Dumville, who dates the manuscript to 997-1016; see Andy Orchard, Pride and Prodigies: Studies in the Monsters of the Beowulf- Manuscript (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1995), 2; and David Dumville, “Beowulf Come Lately: Some Notes on the Palaeography of the Nowell Codex,” Archiv 225 (1988): 63. For more on the dating, see Elzbieta Temple, A Survey of Manuscripts Illuminated in the British Isles: Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts 900– 1066 (London: Harvey Miller, 1976), 72, no. 52; Colin Chase, The Dating of Beowulf (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1981); Kevin S. Kiernan, Beowulf and the Beowulf Manuscript, rev. ed. (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1996), 13-63; Audrey Meaney, “Scyld Scefing and the Dating of the Beowulf—Again,” Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester 7 (1989): 7-40; Michael Lapidge, “The Archetype of Beowulf,” Anglo-Saxon England 29 (2000): 5-41. The foliation of the Wonders is somewhat complicated. Kemp Malone provides an explanation of the circumstances causing this complication, as well as a chart detailing the four numerations: Malone, The Nowell Codex, 12-14. This passage occurs on the first page of the Wonders, identified by Malone as fol. 98v. For simplicity, we number the folios of the Wonders in sequence, beginning with fol. 1v; figure captions also include the British Library’s current foliation system in square brackets. |

| ↑5 | Martin K. Foys, Virtually Anglo-Saxon: Old Media, New Media, and Early Medieval Studies in the Late Age of Print (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2007), 141. |

| ↑6 | Jacques Derrida and Craig Owens, “Parergon,” October 9 (1979): 18; quoting Emmanuel Kant, Critique of Judgment, trans. James Creed Meredith (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1928) on the definition of “Parergon,” (p. 72). https://doi.org/10.2307/778319 |

| ↑7 | For representative imagery from the Winchester School, see for example Heslop and Sekules, Medieval Art and Architecture at Winchester Cathedral; and Temple, Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts, 18ff. |

| ↑8 | Nicolas Poussin, Lettres et propos sur l’art, ed. Anthony Blunt (Paris : Hermann, 1964), 35-36: “Quand vous aurez reçu le vôtre, je vous supplie, si vous le trouvez bon, de l’orner d’un peu de corniche, car il en a besoin, afin que, en le considérant en toutes ses parties, les rayons de l’œil soilient retenus et non point épars au dehors, en recevant les espèces des autres objets voisins qui, venant pêle-mêle avec les choses dépeintes, confondent le jour.” For a discussion of this passage in relation to Derridian concepts of the frame, see Louis Marin, “The Frame of Representation,” in The Rhetoric of the Frame: Essays on the Boundaries of the Artwork, ed. Paul Duro (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 82. |

| ↑9 | London, British Library, MS Cotton Tiberius B.v and Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Bodley 614; London, British Library, Add. MS 28681, fol. 9r (Psalter Map). |

| ↑10 | Meyer Schapiro, The Language of Forms: Lectures on Insular Manuscript Art (New York: The Pierpont Morgan Library, 2005, 10) discusses Mark’s Lion in the Book of Durrow. Schapiro also notes, “The artist of the Lindisfarne Gospels treats the drawing of the figures as if they are of the same pictorial substance as the frame and as if the lines of the bench, the footstool, the curtain, and rod all belong to the same system as the frame” (p. 23). |

| ↑11 | Derrida and Owens, “Parergon,” 30. |

| ↑12 | Susan Kim, “Man-Eating Monsters and Ants as Big as Dogs,” in Animals and the Symbolic in Medieval Art and Literature, ed. L. A. J. R. Houwen (Groningen: Egbert Forsten, 1997), 49. As Schapiro in The Language of Forms writes, “the action of entry into a text, the advancing movement … requires for its realization a frame, an obstacle—not as an enclosure but as a barrier to break through, to transcend” (p. 40). |

| ↑13 | “ne mæg nan man/na ypelice on pt land gefaran” (fol. 5v). This and subsequent citations of the text are taken from our own transliteration and translation of the entire Wonders of the East (Inconceivable Beasts: The Wonders of the East in the Beowulf Manuscript, forthcoming). Stanley Rypins provides an edition of the Wonders in the Beowulf Manuscript: Three Old English Prose Texts in MS Cotton Vitellius A.xv, ed. Stanley Rypins, Early English Text Society, o.s. 161 (1924; repr., Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 1998). For a more recent edition of the Wonders, see Andy Orchard, Pride and Prodigies: Studies in the Monsters of the Beowulf-Manuscript (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1995). |

| ↑14 | Malone, The Nowell Codex, 29. |

| ↑15 | Fol.1v. On foliation, see n. 4, above. |

| ↑16 | Malone, The Nowell Codex, 29. Malone (pp. 30-31) notes that even when numerals are written out, as on folio 127r, line 5, pointing may be used to separate the numerals from other parts of the text. It is not surprising that given the iterations of distance and size in both the Wonders and the Letter of Alexander, those texts show a proportionately high occurrence of pointing in comparison to the other texts of the codex, with as many as twenty-one points occurring on a single page in both texts. |

| ↑17 | Isidore, Etymologiae 3.4.3: “Per numerum siquidem, ne confundamur, instruimur. Tolle numerum rebus omnibus, et omnia pereunt. Adime saeculo computum, et cuncta ignorantia caeca complectitur, nec differri potest a caeteris animalibus qui calculi nescit rationem” (Patrologia latina, ed. J. P. Migne [Paris: Brepols, 1850], 82:156A-B). English translation from The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville, trans Stephen A. Barney, W. J. Lewis, J. A. Beach, and Oliver Berghof (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 90 (3.4.4). |

| ↑18 | Isidore, Etymologiae 3.4.4. |

| ↑19 | Naomi Reed Kline (Maps of Medieval Thought: The Hereford Paradigm [Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2001], 95), runs aground of this problem in her classification of the centaur (called fauni) on the Hereford Map under both “Animals” and “Strange Races,” perhaps owing to the Map’s description: “centaurs are half-horse, half-human.” For further discussion, see Asa Simon Mittman, Maps and Monsters in Medieval England (New York: Routledge, 2006), 47-48. |

| ↑20 | Isidore, Etymologiae 1.4.16: “Unicuique autem litterae tria accidunt: nomen, quomodo vocetur; figura, quo charactere signetur; potestas, quae vocalis, quae consonans habeatur. A quibusdam et ordo adjicitur, quae praecedat, quae sequatur, ut a prior sit, sequens b. A autem in omnibus gentibus ideo prima est litterarum, pro eo quod ipsa prior nascentibus vocem aperiat.”(Patrologia Latina 82:81A). |

| ↑21 | See also Mary Caruthers, The Book of Memory: A Study of Memory in Medieval Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990). Caruthers argues similarly that, for Isidore, “[w]riting is a servant to memory, a book its extension, and like the memory itself, written letters call up the voices of those that are no longer present” (p. 111). |

| ↑22 | Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, trans. Sheila Faria Glaser (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994), 1. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9904 |

| ↑23 | Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, 6. |

| ↑24 | Ibid., 3. |

| ↑25 | Ibid., 7-8. As Baudrillard writes, “Science loses precious capital there, but the object will be safe, lost to science, but intact in its ‘virginity.’ It is not a question of sacrifice (science never sacrifices itself, it is always murderous), but of the simulated sacrifice of its object in order to save its reality principle” (p. 7). |

| ↑26 | Thomas Headland, “Conclusion: The Tasaday, A Hoax or Not?” in The Tasaday Controversy: Assessing the Evidence, ed. Thomas Headland (Washington, D.C.: American Anthropological Association, 1992), 215: “The Tasaday did not deliberately deceive the public, but neither were they primitive foragers isolated for hundreds of years from outside contacts.” |

| ↑27 | Stuart Kirsch, “Lost Tribes: Indigenous People and the Social Imaginary,” Anthropological Quarterly 70 (1997): 61. https://doi.org/10.2307/3317506 |

| ↑28 | One significant exception is the “Generous Men,” who give women to visitors. |

| ↑29 | Foys, Virtually Anglo-Saxon, 52, 67. Foys refers to Anselm, Orationes sive Meditationes, in S. Anselmi Cantuariensis archiepiscopi opera omnia ad fidem codicum, 6 vols., ed. F. S. Schmitt (Edinburgh: Thomas Nelson, 1946-1961), 3:1-91. |

| ↑30 | Augustine, Epistulae, ed. A. Goldbacher, Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum 34:2 (Vienna: F. Tempsky, 1898), 107: “Maior liber noster orbis terrarum est; in eo lego completum, quod in libro dei lego promissum.” |

| ↑31 | Henry Heydenryk, The Art and History of Frames: An Inquiry into the Enhancement of Paintings (New York: James Heineman, 1963), 5. |

| ↑32 | Kenneth Clark, Landscape into Art (New York: Harper and Row, 1976), 47. |

| ↑33 | Clement Greenberg, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” Partisan Review 6 (1939); reprinted in Pollock and After, ed. Francis Frascina (New York: Harper and Row, 1985), 23. |

| ↑34 | Herbert Kessler, Seeing Medieval Art (Peterborough, Ont.: Broadview Press, 2004), 19. |

| ↑35 | Foys, Virtually Anglo-Saxon, 118. |

| ↑36 | Malone, The Nowell Codex, 117 (cock and hen [2R]). |