Larisa Grollemond, Tyler Gunther, Bryan C. Keene, and Mariah Proctor-Tiffany

Recommended citation: Larisa Grollemond, Tyler Gunther, Bryan C. Keene, and Mariah Proctor-Tiffany, “A Conversation with Tyler Gunther (aka @GreedyPeasant)!,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 11 (2025). https://doi.org/10.61302/JHEN9149.

@Greedy.Peasant interview – Huzzah!

Video Interview 1:

Video Interview 2: A Follow-Up Conversation with @GreedyPeasant!

Transcript of Video 1 (A Transcript of Video 2 follows)

Bryan C. Keene (he/él and they/elle): Welcome to Different Visions: New perspectives on Medieval Art, Issue 11 – Introductions to the Middle Ages through Medievalisms. I’m Dr. Brian Keen, and I’m joined by my co-editors to this special volume, Dr. Larisa Grollemond, Dr. Mariah Proctor Tiffany, and our distinguished guest, Sir Tyler Gunther—the Greedy Peasant (@Greedy.Peasant). Thank you so much, Tyler, for joining us today.

Greedy Peasant: Yes, happy to be here. Thank you.

Larisa Grollemond (she/her): So to give everyone a little bit of an introduction to what we’re doing here: We’re so thrilled that Tyler has agreed to talk to us about his introduction to the medieval and medievalism, and what he does on social media as the Greedy Peasant. So this fits into our issue really, really well, because we’re really interested in the ways that people come to the medieval through pop culture especially. And I think nowadays, especially through social media as @Greedy.Peasant. Thinking about the ways that the medieval is presented online, and how people are consuming it and participating in it… Tyler, we’re really excited to get your perspective on these kinds of topics, since you are not a medievalist. Correct?

Greedy Peasant: That is correct.

Larisa Grollemond: To get us started, how did you come to the medieval or sort of why, the medieval for you?

Greedy Peasant: Right. I was thinking about this in preparations for this interview, because there’s a lot of different origins. But I think the beginning was like the Catholic Church I grew up in in Arkansas. It was this Romanesque Revival church that was like built at the end of the 1800s, and my like whole life centered around that space. And it is this like beautiful, like medieval revival space. I just spent like thousands of hours in there, staring at that artwork.

I guess that’s where it began, because there wasn’t like, I mean, other than like Disney Pop culture, of course, but like staring at stained glass, staring at like all of the statuary, I think, is what still informs, like my love of the flamboyance for that time period.

What I thought was interesting was when I started Catholic school there, they started building like an extension to the church. So it was like 1990s-architecture meets like beautiful Victorian Gothic Revival architecture, and I think even in my Little Peasant brain I was like, “Oh, this is terrible! Like this is where we’ve lost everything, because it was just kind of like khaki, and like carpets and wallpaper, and like fluorescent lights…”

And I was like, “Oh, but all the good stuff’s like over here in this, like the detail and the storytelling the visuals. So I think that’s really like where it began. And then, when it like popped up in my life, moving forward like medieval imagery, I could like – I had those feelings baked in from a very early age of like appreciating them.

Mariah Proctor (she/her): Great. Thank you. So delighted that you’re with us. I really love your combination of costume and the medieval, and making it so fun and love to show your stuff in our classes. Tyler, tell us about how your medieval time traveling journey began. How did you start posting? When did you realize, “Oh, this can all go on social media!”

Greedy Peasant: Yeah, I like went to school for costume design, which I think was also informed by, like all the Catholic saint imagery I grew up with, because it is like all these different time periods and countries and national dress represented. And so, after going to school for costume design, I was in this residency, where we made 20-minute shows, and so I made one about King Edward II and Piers Gaveston and their like queer love story. And so I made the peasant outfit for that, and then put it away.

And then Covid happened, and my friend and boss, Robin Frohardt, was like, “You need to make a Tiktok with that peasant costume,” and I was like, “I don’t want to do that.” Tiktok was like very unknown. It was like very like… I didn’t know if I needed that energy in my life, because I was scared of it. And then she’s like, “Well, you’re fired if you don’t,” as a joke. And so then I made the Tiktok, and the rest is like history. So it was really I needed that like push from my friend to do it, because it’s like I had the costume. It’s not like I made the costume for a Tiktok, but she could see how these two could be combined into like an interesting art practice. And then now like here we are 4 or 5 years later. So.

Screenshot of @Greedy.Peasant on Instagram (as of May 5, 2025).

Mariah Proctor: 250,000 followers later!! [nearly 300k now]

Greedy Peasant: Yeah! Cause I was like, “Okay, fine. I’ll do it. And like, I’ll make 6 videos. And then, if it doesn’t work, we’ll just never do this again.” And so yeah, funny that I my instincts were completely wrong. That’s a lesson.

Larisa Grollemond: What has the response been to your persona online and the kinds of videos that you were initially posting? Was that surprising to you?

Greedy Peasant: Yeah, it was very surprising, because at the beginning I was like I had no followers. So I was like, I just have to make something that’s funny to me. And that was kind of the goal, like, I think this is absurd and funny. It’s kind of funny if it flops, because it’s just so niche that I never thought anyone would connect with it, because it’s like medieval reliquaries talking to each other like that wasn’t following a trend that I saw happening necessarily. So yeah, it was a huge surprise.

And that I wasn’t bringing a lot of like academic knowledge to it that I was kind of like just bringing what I enjoyed, and I wasn’t sure if that was enough, but it was enough for some people, which is great.

The famous Greedy Peasant reliquary busts – Amanda, Susan, and Bridgette – at the Met Cloisters.

Larisa Grollemond: I have to ask, how did you choose the reliquaries, or how did the reliquaries come to be such a central part of the videos that you initially got started with. I think, as medieval art historians, we love to see art used in that way – for it to come to life a little bit. I mean we do, for the three of us, but it is niche, and they’re one of those things that you see in a museum or something, and they’re very serious in a way, and to bring some fun and something sort of lighthearted to them. I’m curious how that got started for you.

Greedy Peasant: Yeah, that was like one of the very first Tiktoks – making reliquary videos – because I was still too nervous to like put on a peasant costume and talk to no one. And so my friend was like, “Well, why don’t you try like a filter? Because that will give you a little like deniability…” Those reliquary busts at the cloisters have just like, always been a favorite of mine, and when you see them in person, you just imagine them talking to each other because they have so much personality. And then when you learn that they also store, like corpse chunks, you’re just like, “Oh, oh, they do like literally have an inner life… like they aren’t just statues,” you know? So they were like the perfect inspiration. They brought so much personality that I felt like just them making like very boring chit chat was still interesting to me, because inside them is like a dead body part. And that was like at the very beginning.

Larisa Grollemond: I can’t see them without thinking of them talking to each other now. There’s something about reliquaries in general that, I think has been animated for me by your content and really sort of thinking about yeah, like, what would these things say to each other, or sort of what would they say to us if they could talk? And I think that’s like, ultimately, what we’re trying to do as art historians in some ways is get objects to speak in some sense. I’m so taken by the kind of popularity that the reliquaries have had, not just for medievalists and medieval art historians, which is a very niche group, but then the way that they’ve resonated with other people online who may not have any familiarity with the medieval. Has the response from people who maybe didn’t know about that background or that art been surprising in some way to you, or different than what you expected?

Greedy Peasant: I think so. Yeah, it’s like, well, I find it’s interesting with like practicing Catholics like who I know. It’s like… It’s such a Catholic thing, these reliquaries, but they didn’t really teach us about them in Catholic school. So they’re these really Catholic thing… That’s a lot to take in. We’ll let you discover that later, because you think, after like thirteen years of Catholic school, you would have like, you would have known a lot about reliquaries. But there are these like pockets of that faith that can still surprise someone in like their fifties and sixties where they’re like, “Wait, what? What is in there?” This is someone who’s like at church every day or every week. And so I find that fascinating, not good or bad, but just that.

It’s a fascinating history of that faith. Some of it’s like really, really grotesque, of course, and beautiful at the same time. And that’s been the surprise where I’m like talking to people who are like, “Wait, they’re what?” And it’s like, “No, this is a part of your whole thing, right?” And so I mean, I’m talking about family members. Yeah, I think that’s interesting… the like attraction and repulsion from those elements of it.

Bryan C. Keene: And it’s so interesting, as Larisa was saying, you’ve taught so many medievalists a lot about the Middle Ages as well in terms of the way you’ve animated these objects – helping us to think about objects differently, to think about how we curate the objects in these spaces, how we engage the material with our visitors.

Edward II by Derek Jarman (1992). Photo: Bryan C. Keene.

Even when you mentioned Edward II and Piers Gaveston, I just keep thinking of my first introduction to their love story was through Derek Jarman. And I think for some people, you know, maybe you’ve given a similar kind of introduction with some really nuanced and thoughtful videos every time you post. I’m like, that’s so brilliant because you’ve enlivened an aspect of medieval history or art or culture that we see in scholarship, in black and white in print. But you’ve really animated it quite literally, but also with real heart, and hoping, as you said, that people think again about their own upbringing, religion, or culture.. Especially in the U.S. where we’re so far from that. Those were just a few thoughts that went through my mind.

I’m curious if you had advice for others who might be thinking about how to get started on their own sort of medievalism journey, talking, reflecting on your own sort of hesitancy to start, and Larisa is, of course, one of the other great Instagram and social media personalities for medieval, so what advice do you have for those out there, hesitating to get started?

Greedy Peasant: Yeah, I think I had two thoughts about this. The first was me acknowledging it wasn’t just like obvious to me at the beginning, like there was so much like baggage tied up with like Catholic art, and my experience being a queer person, growing up in a Catholic church, that it wasn’t something I was ready to just like, jump into and make a career about. I like felt like, there was just a lot of triggering, or whatever for those spaces, and thinking like you needed to fully believe in that faith to engage with that art, like that was the ticket. To enjoy that art was to have that faith.

But then, of course, you get older, and you realize, like I can approach this for the craftsmanship and for the beauty and the absurdity and the humor, and that you’re not doing it from a disrespectful point of view. You’re not doing it to make fun of it, because it felt like it was one or the other. Either you like believed in 100%, or you were making fun of it. But then, of course, it’s like, “No, there’s the art history perspective, where you’re just like you’re learning about the people who made them. You’re learning about how they made them.”

There was like so much joy in like finding that permission for myself of like, “Oh, I can just enjoy it as art,” and like as so many people already knew, it just took me a while to get there because I thought I just thought there was like this like gatekeeping that wasn’t really existing like I was kind of like had that in my mind. But I just wanted to say that, because sometimes people are like, they don’t want to go in Gothic Revival churches because they’re like, “That gives me bad feelings,” and that’s fair. For me I could trick myself eventually to be like no like I can go, and just like love that stained glass and respectfully, and really enjoy that. So that was one thing.

The Competition in Sittacene and the Placating of Sisigambis (detail) in Book of the Deeds of Alexander the Great, illuminations attributed to the Master of the Jardin de vertueuse consolation, about 1470–75. Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XV 8 (83.MR.178), fol. 99.

And the other thing was like the gender of it all. For me it was like looking at the masculinity and the way it’s presented in the Middle Ages, like, I still find so exciting that it’s like, because I grew up this very narrow, like 1990s Arkansas version of what a man is and anything flamboyant or colorful was like negative but those men still think of like the Middle Ages men as like real pinnacles of manhood. And so, seeing those men in their fabulous dress, and realizing like, “Oh, this is all just like contrived,” was like also a nice discovery of like masculinity, is very fragile, as we all know, and just like the Middle Ages kind of like is a great example of that, as far as like how like fashions change, whims change. What makes a man changes? And so all the pressure I put on myself growing up was kind of like could go away when I’m like, “Oh, like I’m dressing as absolutely a man just in like 1444.” And so, you know, “Fight me!”

What’s been interesting is like having that historical basis to pull from, because it feels like in your book that you sent me, The Fantasy of the Middle Ages, like, it’s great to see other artists taking inspiration. It’s like, “Oh, it’s not my solitary journey. It’s like, oh, so many people are inspired by this time period, of course!”

But yeah, no, there are like some roadblocks at the beginning. It’s like, not always obvious that it’s going or that you’re going to connect with it. I think that’s my long-winded answer.

Larisa Grollemond: Could you talk a little bit more about like the creation of a real life community around the Greedy Peasant account and some of the Pride events that you’ve done? It’s like mobilizing medievalizing spaces, too, but to create something that happens off social media and actually in real life. Could you talk about some of those events? And maybe the kinds of things that you’re hoping to achieve with those sorts of events.

Pathways of Pride @Greedy.Peasant for Pride 2024 at the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine, New York.

Greedy Peasant: Right? I mean, the community that’s formed around it is like the most incredible thing, because it’s happening outside of me. Like it’s really me on the screen making most of it. But then it’s like the engagement is so wonderful and like the tone that I was like trying to set at the beginning has been totally improved by the community, like everyone seems to like it. There’s not a lot of negativity. Like the Internet is a really dark place, but the Greedy Peasant community people are finding such ways to enjoy the work in such positive ways, in such humorous ways that I’m constantly trying to remember, like, how lucky I am that it’s because the Internet can go a lot of different ways, and being a peasant, it could be interpreted a lot of different ways. But no, it’s been thrilling. And then to get to do live events like our pride Eve event which we did last year, and we’re doing again this year, was the ultimate manifestation of like people coming being together, not knowing each other. [sorry there’s a siren…]

We’re really encouraging them to dress up and really like push the boundaries of how they would normally dress and kind of like creating an environment where, like, you can take that risk because everyone there will be like supportive of you and be encouraging you, and it’s like exciting to me that there is a community in which, like I’m not a very like fashion risk taker in my day to day life. But I’m like well for Pride Eve though I can like I can really dress up. I think that’s a feeling other people are feeling which makes me very happy, because in our modern day to day, like we don’t really have a lot of reasons to like experiment with how we present ourselves. And the way that I thought growing up like there’d be a lot more like masquerade balls in my life, and just like really like glamorous events to attend. And so it’s fun to get to like.

Mariah Proctor: Met Gala next year!

Greedy Peasant: I was like, “Oh, surely I’ll just be like swatting away those types of events.” But then you’re like, “Oh, I really have to wait for the next wedding to like dressed up?” But this Pride event’s the ultimate queer community embracing and like being at the cathedral is great, because it kind of like just matches the energy of that space. Like it’s a huge, flamboyant, beautiful space like dress accordingly, like the Gothic architecture lends itself to like the biggest manifestation of an outfit you want. So that’s exciting that you’re not going to look out of place in a Gothic cathedral wearing the most fabulous outfit, which sometimes you don’t make that connection because you think you need to dress like conservatively in a church, but it’s like, it can take it. Yeah.

Larisa Grollemond: In some ways it’s sort of lovely because it intersects with the kind of ethos of a Renaissance Faire or another sort of period space that allows for some experimentation and freedom of expression and dress. And I think it’s cool to see that happening in other kinds of spaces that are not quite as themed. I love the idea of church architecture like calling for that kind of that kind of response.

Greedy Peasant: Because when I think of like church clothes growing up was like your most boring khaki pants and button down shirt. But then it’s like, “Oh, but the space really is asking for more!” And you think of like big church hats – which my Arkansas Catholics did not wear – but like there is such a dressing-for-the-occasion: it’s something I like that we are embracing, which is great.

Bryan C. Keene: And the celebrants in the whole liturgy can be quite flamboyant as well with their full flowing vestments. And I mean, that’s to me another big draw is watching the whole celebration of moving objects, candles, and books, and elements..

Mariah Proctor: Absolutely.

Bryan C. Keene: It’s so pageant-like, right?

Greedy Peasant: Yeah, that’s where, as a former altar server, of course, I’m like, “Oh, we did go from ultra server to theater degree pretty quickly!” Sometimes it’s like, those are completely separate parts of my life. And it’s like, well, lots of overlap.

Bryan C. Keene: There are other medievalists who will be listening to this, that also have a fascination with vestments, and are themselves celebrants in real life, or that, you know, in our conferences, we attend the medieval dance, not always in regalia or costume, but there are jousts at other medieval conferences and hands-on activities to make astrolabes or pewter pilgrim badges. So we’re also sort of experimenting in our own spaces. But it doesn’t always translate in day-to-day life.

Greedy Peasant: Yeah. Yeah. And I like that at this event, you don’t have to dress accurately. Like nobody’s holding up a medieval rubric to your outfit. So some people were like 1960s vintage, some people wore medieval, some people wore like futuristic Utopian, but it all seemed to work together, which you just don’t know until you see it. But I was just thrilled that someone in a peasant costume looked great next to someone in a completely different interpretation of that prompt. Because, yeah, I just people, you know, they’re like, “Well, maybe this isn’t historically accurate, and I’ll be laughed at.” But it’s great to find spaces where if you can go a hundred percent historically accurate, and everyone’s on your side, and you can just do like your version of it, and everyone’s there with you, too. So these like moments where you get to try out different visuals is exciting.

Mariah Proctor: Can I ask about your Saint Snap System, how that came about? I just love it. It is so medieval. And yes, there you are: You’ve got the hat. Just how you use snaps on costumes to make it so interchangeable. And I really like even the unadorned snaps they evoke mail – you know metal on clothing – and it’s almost like ASMR as you click them on in your videos. I love that. And just the idea of reusing textiles is so medieval.

Greedy Peasant: Right, you know: Never throw away anything. That’s where I kept wondering like, “Why don’t we dress with more embellishment, more flamboyance? Because we do have access to more materials than they did in the Middle Ages…”

But I came down to like laundry was the culprit, because it’s like we don’t want anything that can’t be like thrown into a washer-dryer – myself included. So it really was like, “How do you create like super embellished, interesting garments that are also washable?” Because it’s like, I don’t go to the dry cleaners. So it’s like really removing the barrier of like, how do you make this so accessible? And that was how we got into these snaps that are very washable. So all the decorations can be taken off and removed and exchanged.

That was really the that, and also like the pace of social media where I was following other fashion accounts, and it seemed like they were making a different costume every week. And I was like, “I just don’t understand it.” So it’s like, I don’t really enjoy the first 99% of making a costume. I like the embellishment. So it was also like, “Okay, let’s just… let’s make one base!” And I’ll hot glue stuff until the end of time. But it’s those kind of like things combined, where I don’t think I would have developed any of that without this social media context. But it’s been really exciting, and I think not to turn this into me asking this question, but, in medieval times, they must have – not that they were using snaps…

Mariah Proctor: Like you’re saying reused materials? Absolutely!

Greedy Peasant: Yeah, I’m like there is something to like, they wouldn’t cover something in jewels, and then put that in a closet for five years.

Mariah Proctor: Yeah, you reuse everything. You never throw away anything. If a textile wears out, you reuse it, you cut it down, you give it to the church. It has fifteen lives.

Greedy Peasant: Right! And not a lot of it exists, which is sad for research, but it also is like exciting within this way of making costumes of things that aren’t single use. Things can just keep changing. So yeah.

Mariah Proctor: Well, thank you so much. Tell us why the Middle Ages are the best. According to you, Tyler.

Greedy Peasant: Oh, yeah, well, this changes like every day. But my answer today is like, I think it’s to me it’s the saints, because I’m kind of obsessed with like medieval saints, and how they created all of these reasons to celebrate all these different interesting feast days and artworks and recipes. And I think that’s like uniquely medieval to me.

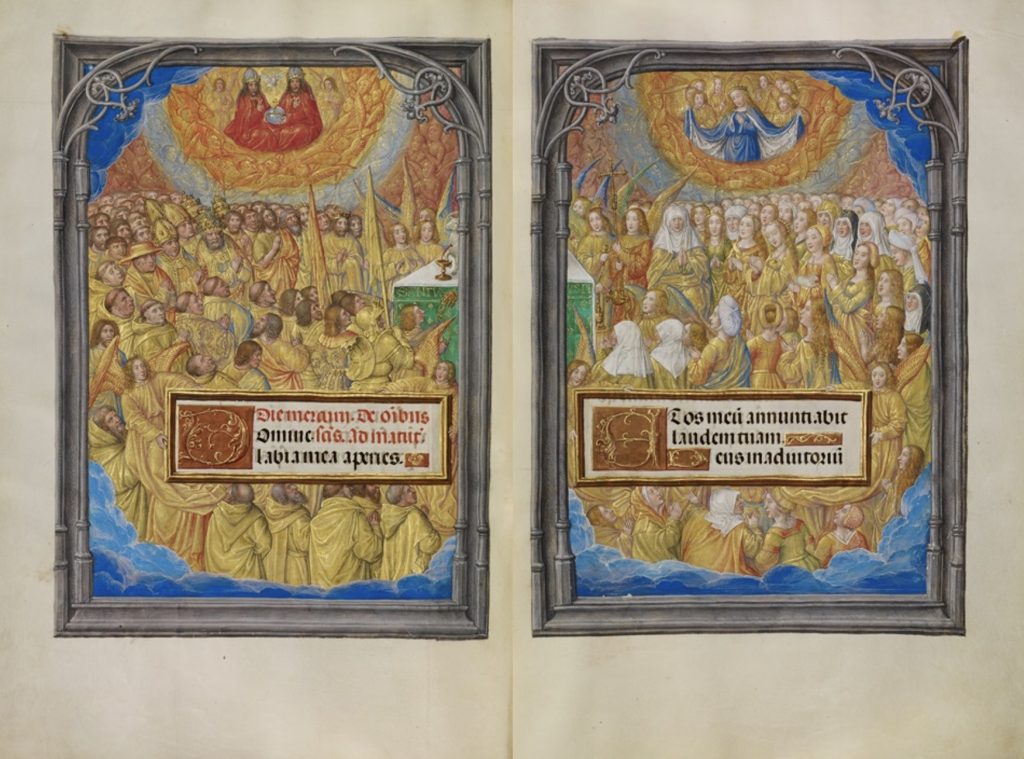

Male Martyrs and Saints Worshiping the Lamb of God; Female Martyrs and Saints Worshiping the Lamb of God in the Spinola Hours, about 1510–20, Master of the James IV of Scotland. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig IX 18, fols. 39v–40.

I’ve been thinking a lot about like holidays and celebrations, and how everything’s become very like corporate, and under capitalism we’ve like created these new rules of how we’re supposed to celebrate holidays. But I’m really attracted to these like niche, interesting patron saints, for, like pharmaceutical reps, and just like them, having their own holiday and their own like recipe to make on that holiday, and their own thing to tie to a tree, and to me that feels like this like interesting medieval outlook on life. So I don’t know if that’s the most cohesive answer. But that’s where my brain is. It’s like they kind of give you permission to make these like interesting decisions that other time periods, I think, don’t lend themselves to, whereas you’re like, “It was the Middle Ages!” And people will go, “Oh, oh, okay, yeah.”

Larisa Grollemond: Moving forward, I mean knowing that social media is always hungry for new content and kind of new things, What do you see, if you could give us maybe a little sneak peek into the future of what you see Greedy Peasant doing. Will you continue doing some of your favorite things? Will you introduce new series, new kinds of things? What do you hope for the account going forward?

Greedy Peasant: Well, I think it’s like a continuation of this, like holiday thing is where my brain is. It’s like trying to like carve out moments in time for yourself, as the world is kind of like doing what it’s doing that like looking back in time to be like. Here’s a little holiday for you. Here’s like a little morsel of happiness that capitalism hasn’t gotten its hands on is something I would like to explore more in the future. Because, like holidays are the best like. That’s what I loved growing up was getting to like, decorate and celebrate. And there’s that like meme that goes around that like peasants had, like, you know, 3,000 more holidays than we did, which isn’t like totally accurate. But there is that impulse. I’d like to do more research along those lines of like finding these traditions that people made to make themselves happy and to celebrate that. We’ve kind of lost over time, especially in America where those traditions haven’t survived.

Medieval peasants meme. Source: The internet. 😊

I think within the social media hamster wheel, I was like, I need to stick to the liturgical calendar. I kept going on these different tangents, and it’s like, “You missed Easter!” Like, “Easter is big for us!” Like, “Palm Sunday is big.” So I’m hoping to do more research along those lines of like, “What were people actually doing on, you know, July 12th?” Is there a feast day I can talk about? So yeah, that’s me trying to create a framework for this very like a zig-zaggy kind of like career on social media.

Bryan C. Keene: July 12th is the Feast of Saint Veronica – there’s a lot you can do with textiles there – so, so much! I mean, Tyler, Larisa and I, we had this idea ages ago at the Getty, that you know we would read a book of hours every three hours or something to try to get in this medieval spirit, or like open up a choir book and just listen to choral music, because every 3 hours you need a break, you need to hear some uplifting reading or hear some great music, and I mean it would be fun to do a kind of day in the life of a medieval Greedy Peasant, you know just, “Here I am at the early morning hours, reading my book of hours, and then visiting my relatives…”

Larisa Grollemond: Only prevented from doing that by the fact that I would have to wake up in the middle of the night to pray!

Greedy Peasant: It’s a great break from other things, but not from sleep.

Bryan C. Keene: Not from sleep.

Larisa Grollemond: Yeah. The good news is, there’s a feast day every day, so there’s always something to celebrate, always something to think about. I mean, I find that that’s so interesting because people are constantly online and sort of constantly on social media. It is a little bit of a medieval impulse to be kind of celebrating and engaging with that on such a regular basis and sort of on such a scheduled basis almost, that I think you’re handling something…

Mariah Proctor: Sewing a thread through cloth, you know, making a stitch, stitch, stitch.

Greedy Peasant: Yeah. And it’s been nice, like, because I didn’t know how long this would all last. So to get to already get to return to some things like Palm Sunday now, like four times has been interesting like, and that you think social media has to be new. Every. Single. Post. But people actually are craving a little bit of like, “Oh, on Palm Sunday that medieval peasant posts the same video.” And it’s really sweet to now be a part of a tradition. But yeah, exactly that kind of like medieval impulse that we all have.

Bryan C. Keene: Well, we’re so grateful that you’ve spent time with us. I mean, we could talk probably for hours, I know, but it’s so amazing that you’ve given us your time, and I do hope at some point, you know, you’re able to continue to venture beyond medieval New York. You know, there are so many other medievalists who are looking at medieval Baltimore, and we’re looking at medieval California. So you were already ahead of a curve in what academics are doing so, you’re totally on a path that feels parallel, but also so much more adventurous and exciting every day. So thank you eternally from the bottom of my heart, from our hearts for spending time with us.

Greedy Peasant: Oh, I appreciate this so much, so I’m glad it all worked out, and I’m excited to read the other articles in this issue, because it really will help me, as I’m navigating things. So yeah, thank you.

Mariah Proctor: So nice to meet you.

Larisa Grollemond: Yes.

Greedy Peasant: Yeah, it’s nice to meet you all!

Transcript of Video 2: A Follow-Up Conversation with @GreedyPeasant!

Larisa Grollemond, Tyler Gunther, Bryan C. Keene, and Mariah Proctor-Tiffany

Bryan C. Keene: Okay, maybe ask that again. Cause that was so good.

Greedy Peasant: Well, I was like wondering what the the barrier that you guys when you’re trying to like, bring someone over to the medieval side of things like, what’s the barrier you’re experiencing that people have to get past? You were saying like that it’s this feeling that people don’t want to feel dumb. They don’t want to like, look at art, and like not know the context, not know the history. And so I just think that’s like such a real feeling. And I wonder but if you want to expand on what you were saying before.

Larisa Grollemond: No, I mean, I think we’ve come up with kind of different strategies for doing this and it’s similar to what you do in a way that it’s about making it relatable or making it relevant to people’s experience today, too. And seeing things like, you know, political struggle, or, you know, gender based struggle, right? You know, social identities being, you know, manipulated or performed in different ways. There’s so much there that is like very human and very consistent that you have to uncover those layers of like historical context and kind of present them in a way that makes it more obvious, I think, for people because they don’t. It’s harder to walk up to a piece of medieval art and get it, or feel that you get it.

Greedy Peasant: Right, right.

Larisa Grollemond: It’s a little different. It’s also like, you know, the art education that we get as sort of popular culture is Impressionism. It’s Abstract Expressionism. It’s a lot of 20th- and 21st-century art, which is, you know, fine. But we, we get less, I think, introduction to older art. And so it is more difficult to approach with a feeling of knowledge or a feeling of like immediate grasping. Because I think we do get some renaissance, of course, but then it’s like, “Whoa! Everything else… I’m not sure about that.”

Greedy Peasant: Yeah, yeah.

Larisa Grollemond: How to deal with it.

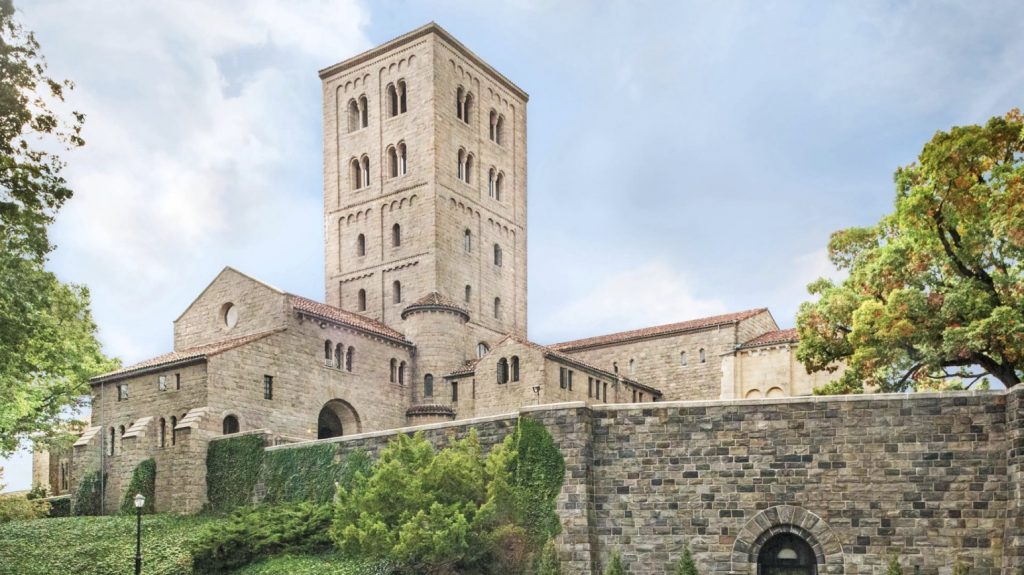

The Met Cloisters. Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Greedy Peasant: I know this, like bias is just interesting, because once people get past the hurdle, it’s like, “This is incredible!” But I remember the Met Cloisters saying, “People think it’s a church. So they approach the art as if they have to be quiet and prayerful.” And I was like, “Oh, that is a huge barrier when you’re trying to program there when people think you’re a church.” And the museum people were like, “Please talk like, please!” And that’s just like baked in for some people, some, and that’s like your day-to-day is, and my day-to-day. I guess it’s just like, how do you be like, “No, it’s okay”?

Larisa Grollemond: It’s okay to have a like kind of a free interpretation. Sorry, Mariah.

Mariah Proctor: Go ahead. No, I was just going to say, that’s why what you’re doing is so important, and why this issue is coming into being is to make it more approachable and to welcome. You don’t have to know everything. You don’t have to have a perfectly accurate costume from 1400 to make these things much more open to a variety of people and creativity, and to use the Middle Ages as a launching point for further creativity. I think we’re in a time of sea change when that accuracy isn’t the, you know, most important factor, and I think the Middle Agers are also really inviting, because there’s so much media around it. You know all the movies, the things that, you know, the issue is dealing with. So there are so many entry points. And then what you’re doing, and hopefully what this issue is doing, also opens it up for so many people, and lets us reinterpret it. You don’t have to be reverent. You don’t have to be so serious.

Larisa Grollemond: Social media has changed this a lot, too. I mean, it’s sort of been interesting to see museums get on social media. But then other kind of independent historians and other kinds of creators are on social media and do different things with it. But I would say that, like academics, have been slow to the platforms, and are still very slow to…

Greedy Peasant: Yeah.

Larisa Grollemond: Take them up in creative ways. And so it’s almost like we need people like you who are not necessarily like crippled by the need to like, get every exact fact correct to present it.

Greedy Peasant: It’s nice that I don’t have the barrier of knowledge. And like, really, because if I was talking about another topic like costume design can be very like, “Oh, that seam is wrong. You’re a fool,” whereas this I’m kind of like, “Well, I’m talking about what I see with my eyes.” But I understand. Yeah, it’s hard to get up there when you’re like. You did not reference this document in your 30-second Tiktok. It’s like a lot, but I guess.

And I don’t want to keep you, but I was like, there’s also this thing of like the medieval torture museum is some people’s like main reference for that era which I find, because with my work, I’m really… I’m not talking about wars or torture. And I’m like, but to some people that’s like their point of reference is like, just like, “They killed people in seventeen horrible ways. See how.” And like is that something – that energy – people are bringing? Or are we kind of like past that hopefully.

Torture Museum: Medieval Exhibition. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Larisa Grollemond: Yeah, that’s a huge thing. I mean, when I do my little videos for the Getty’s account, I always joke with my social media producer that like there’s truthers for whatever topic it’s going to be like, it’s like a Bro who saw a history channel special once and is like, fully convinced. Or it’s a very yeah, like a militaristic kind of history, which is one kind of history. But it’s not the whole history, right? But yeah, I would say, like the vision of the Middle Ages as the Dark Ages is still extremely prevalent in pop culture, and so like moving beyond that to like introduce color and humor, other kinds of more complex things… It’s always an uphill battle.

Greedy Peasant: Yeah, I’m now so far like on the other side of things. But then I remember like, oh, right like should I be? Should I be talking about torture more?

Mariah Proctor: No!

Larisa Grollemond: No!

Bryan C. Keene: No!

Greedy Peasant: I don’t want to. But the truth is, like we’re terrible in this century, like there’s a lot going on.

Larisa Grollemond: Yeah, I mean the torture, too. It’s like a lot of that stuff is medievalism like it’s. It was something created in the Victorian period and read back into the Middle Ages. There’s like a lot of fake torture devices and things like that, too. So…

Greedy Peasant: Yeah, yeah.

Larisa Grollemond: It’s like a self-perpetuating myth in some ways.

Greedy Peasant: Right? Right! No, I just. I needed to ask that while I had you three.

Bryan C. Keene: And they’re going to get enough through Game of Thrones and House of the Dragon, anyway.

Larisa Grollemond: Exactly.

Bryan C. Keene: For better or for worse.

Larisa Grollemond: What do we call that in the book, Bryan? It’s like the dirty Middle Ages?

Bryan C. Keene: The gritty version.

Larisa Grollemond: There was this whole desire, for, like…

Bryan C. Keene: The real, most authentic version…

Larisa Grollemond: It’s like the.

Bryan C. Keene: Muddy.

Larisa Grollemond: With the with the gray-scale filter.

Greedy Peasant: Yeah.

Larisa Grollemond: You know, like where nothing can be fun. No one can laugh, you know.

Greedy Peasant: Right.

Larisa Grollemond: There’s really like a dourness to it which is so contrary to the real medieval experience where there is a lot of humor and color. And you know, there’s material survival that proves otherwise. People don’t always want to see that, or they don’t want to always have that like stereotype challenge, I think, is really the thing, too, but it keeps getting reiterated by pop culture.

Greedy Peasant: Yes, yes. Yeah, it’s definitely been like, because at the beginning I was like, “Oh, they’re just like us.” And I was like, “Well, like my sense of humor, is informed by Sabrina, the Teenage Witch.” But they still had a sense of humor like…

Larisa Grollemond: Yeah, absolutely.

Greedy Peasant: …by their own references. Yeah, there’s not a lot to support for that in pop culture.

Medieval poop humor in the Vidal Mayor, Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XV 6 (83.MQ.165).

Larisa Grollemond: No, I mean something Bryan and I were always talking about was like medieval poop jokes like there’s totally just like, there’s so much stuff that is actually quite funny now as it would have been then. So it’s not that they’re so different. But we still find things like, fundamentally funny as humans that like that hasn’t changed.

Bryan C. Keene: And in, like every church that has some of that architecture, they’ll still tell you the jokes today: “Do you know about this figure, you know, shitting on the column. Do you know about this one vomiting out the window?” “Yes, we know.” But like for 700, 800, 1,000 years in some of these places, they’ve been telling the same joke to every passerby. And I think you’re right that we have to remember the joy. That’s what we’re also thinking: Sometimes our colleagues only admit to the “guilty pleasure” of medievalism, like you can admit to loving Sleeping Beauty for the pageantry and the wonder of Eyvind Earle. That’s fine, and you can still be a serious medievalist. Taking it seriously and recognizing that it’s funny, is okay, too. They don’t have to be mutually exclusive.

Larisa Grollemond: There is a way, too, that I think academics try to make serious things that are not serious like there’s, you know, for every academic pointing out like a guy pooping in the margins of a manuscript, there’s an academic being like, “This is the real religious, theological, liturgical reason for that guy pooping in the margin.” And there’s like it, doesn’t need to be that deep.

Greedy Peasant: I know. I have found that as well. I’m like, “Oh, I would love to have this detail,” and then you find, like the hottest take about that detail. And it’s like…

Larisa Grollemond: Yeah.

Greedy Peasant: “I guess I can?” Yeah, no.

Larisa Grollemonds: Like things can just be fun, you know.

Greedy Peasant: And I don’t think every medieval peasant would have known this specific hot take like, maybe they would have just seen that symbol and thought…

Larisa Grollemond: Totally.

Saint Lucy, Francesco del Cossa, about 1473. National Gallery of Art.

Bryan C. Keene: Or like Saint Lucy’s eyes can just look like runny eggs on a platter. You know. It can be funny.

Larisa Grollemond: It can be like, “That’s weird and gross and…”

Greedy Peasant: It’s really and having the internet’s perspective on these like moments where everyone’s asking me, “Why does Saint Lucy have eyeballs in her head and on a platter, and it’s like, “Well…”

Larisa Grollemond: Because an artist faced with that problem. And you’re like, “I mean… She’s like a saint, so she’s holy. She’s divine. Of course she has her eyes now.”

Greedy Peasant: Yeah, yeah.

Larisa Grollemond: Like it makes sense, in a way. But yeah.

Greedy Peasant: But they can also say, “It doesn’t totally matter.” Right? Like it’s a myth to some degree. And so, it’s just funny that everything needs to make sense through a certain lens where I’m like there are so many ways that her eyeballs may have been removed from her head that who knows? Like there are so many stories and interpretations, which I appreciate, of course, people asking. But it’s like, “I don’t know.” There isn’t like a deep theological reason as to why she has eyes in her head and eyes on a plate. It’s just kind of like what that artist chose to do so. It’s just nice to have you say similar things, because sometimes like, should I know?

Larisa Grollemond: People are. I keep getting interviewed for these little news stories and little magazine stories about like the popularity of fighting snails and things that have like really grasped the popular imagination about the Middle Ages, and like the fighting rabbits, the snails, all these kinds of things. It’s like, I don’t have a great answer for that, and it’s not that there’s one answer for it, either. So it’s like, maybe dependent on the book, or the time, or whatever and I think people do want there to be sort of one definitive answer. And I think the thing about the Middle Ages that maybe makes people uncomfortable, but which is also really fun, is that like there can be multiple things that are important and that mean something like simultaneously, which is why, I think the reliquaries are an interesting case study here, because they always mean something slightly different for different people and in different contexts. And I think the way that you’ve made them mean something different, for, like a 21st-century audience, I think, is awesome, and to have them sort of like have a new life in that way is, is really cool, and I think deeply medieval in a way.

Greedy Peasant: Oh, okay, good. No. That’s also so helpful to hear. Cause there is, yeah, there is a social media impulse that everything has to be perfectly explained quickly and cleanly. History doesn’t work like that. And you guys know that better than I do.

Larisa Grollemond: Totally.

Greedy Peasant: But yeah, you can’t add thirteen footnotes at the end of a Tiktok. So you kinda have to hit the big points. And then people in the comments like sort it out or do their own research like you just kind of got to but…

Larisa Grollemond: I think that’s the thing that makes academics uncomfortable: there are no footnotes.

Bryan C. Keene: But I like that. People in the footnotes will sort it out. Don’t you wish academics could just sort it out in the comments? The comment that’s not a question…

Greedy Peasant: Yeah, people are really wonderful. Sometimes they’re like, “Actually, here’s a helpful source.” So that’s been the nice part of the community. So yeah.

Mariah Proctor: We’d love to be in touch with you, going forward, you know, in any way that would be helpful to you or, you know, further projects. So.

Greedy Peasant: Oh, yeah, absolutely. Yeah. Let’s stay in touch. I’m going to disappear back into peasantry. But we should definitely stay in touch, because the more this keeps growing and changing, it’s always so helpful to have you all to talk to, and like every medievalist, has been like so welcoming. And of course this means a lot to me. So thank you!

Larisa Grollemond: Somebody making the Middle Ages fun and relevant! So you know, we’re in!

Greedy Peasant: I’m trying to.

Bryan C. Keene: And we’ll be sure to link the Patreon!

Greedy Peasant: Thanks!

Mariah Proctor: Truly. Yeah, thank you so much.

Greedy Peasant: Yes, thank you all.

Larisa Grollemond: Bye, guys.