Cathleen Hoeniger • Queen’s University

Recommended citation: Cathleen Hoeniger, “Reading the Landscape in the Camposanto Thebaid,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 12 (2025). https://doi.org/10.61302/PNYB4756.

Introduction

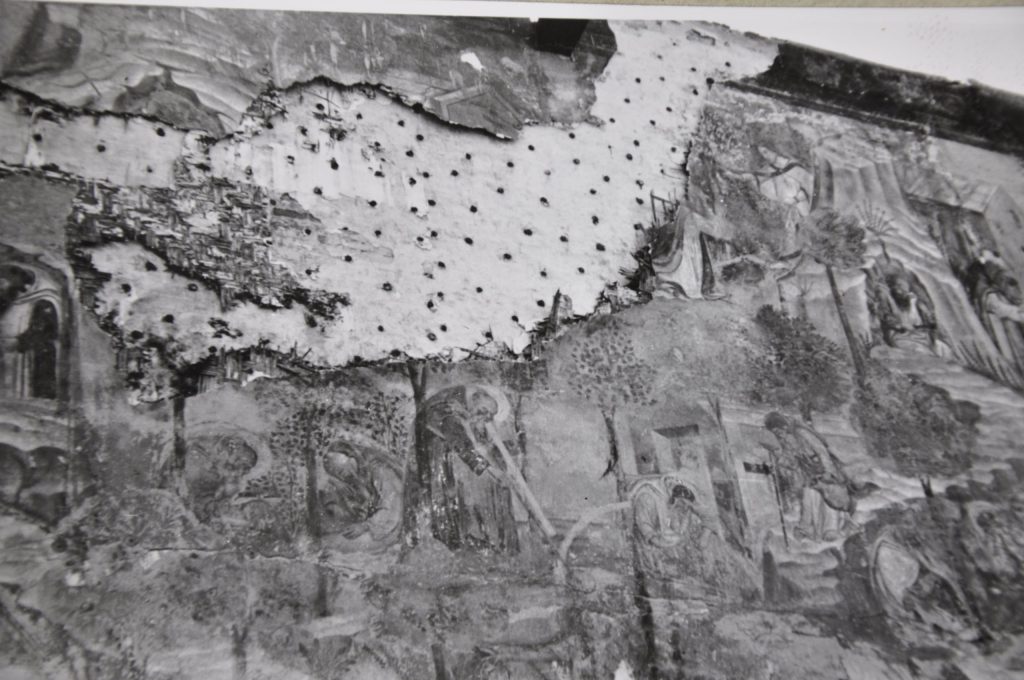

Fig. 1. Buonamico Buffalmacco (attrib.), Triumph of Death, Last Judgement and Inferno, and Thebaid, c. 1337-42, south corridor, Camposanto, Pisa. Frescoes rehung after conservation and transfer to new supports. Condition in March 2019. (Photo: Geoffrey Hodgetts)

Among the frescoes that decorate the Camposanto in Pisa, the Thebaid (or Stories of the Desert Hermits) appears as part of the cycle of three very large murals, which are attributed to Buonamico Buffalmacco and dated c. 1337-42 (Fig. 1).[1] While most writers have been engrossed by the macabre passages in the Triumph of Death and the Last Judgement and Inferno, some have probed the more remote imagery of the Thebaid (Fig. 2). To discover the meaning of the fresco for late medieval viewers, scholars have concentrated on the figures of holy men and women that populate the scenery. These portrayals have been connected to a collection of stories of the hermits that was available in the volgare in Pisa, and associated with the Dominican practice of including exempla from the lives of saints in their sermons. In this article, however, I will steer a different course by focusing instead on the expansive and complex landscape setting of the Thebaid.

Fig. 2. Buonamico Buffalmacco (attrib.), Thebaid, c. 1337-42, south corridor, Camposanto, Pisa. Fresco rehung after conservation and transfer to new support. Condition in May 2021. (Photo: Sailko, Wikimedia Commons, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0)

Methodology

Since this study will investigate the way the landscape contributes to the meaning of the fresco, one initial question to consider is how the approach corresponds to environmentalism in the humanities. When broaching the theme of the natural environment in the Thebaid, it is important to recall that the so-called “fathers” of eco-criticism, including Alexander von Humboldt, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, emulated the hermits because of their closeness to nature. For these 18th- and 19th-century nature lovers, the world the hermits inhabited was an unspoiled wilderness and their intimate relationship with nature was inspiring.[2] Whereas Humboldt believed it was in the mystical eastern deserts that the creator could be apprehended through the evidence of design in nature, Emerson and Thoreau found that America’s vast forests were similar places of silence and seclusion where one could listen for the truth.[3] A more overt debt to the hermits is apparent in La Thébaïde en Amérique (1852) by the Catholic priest Adrien Rouquette in New Orleans, who envisions the American wilderness as the locus for spiritual journeys in the footsteps of the desert fathers.[4] Although scholars who practice eco-criticism today seek approaches that are more relevant to contemporary ecological concerns, the inspirational value of the eremitical literature for naturalist writers like Thoreau underlines the primacy of the landscape for the conception of the hermits.[5]

When interpreting the Thebaid, most scholars treat the landscape like a stage setting for the drama and pass over it relatively quickly.[6] But, as the earliest writings in Greek on the desert fathers intimate, the landscape was integral to the characterization of the eremitic life. In a physical sense, the hermits were represented as inhabiting geographical locations in Egypt and the Levant, and in a symbolic way, the environment took on allegorical meaning reflecting their spiritual journey. This article will suggest that the landscape in the Thebaid can be interpreted in a comparable way: from one vantage point, salient features of the topography of Egypt come into focus, but from another perspective, the devotional path forged by the hermits can be discerned. However, because the fresco has a complicated and fraught history, some background is necessary before the representation of the landscape can be explored.

The Original Context and Present Condition of the Thebaid

As those who study Trecento painting know well, before the 1970s, the cycle of three frescoes was dated after the Black Death of 1348 and the attribution was contested. But critical insights by Joseph Polzer and Luciano Bellosi have led to a general consensus that Buffalmacco painted the frescoes about a decade before the plague struck Tuscany.[7] Crucial information on the sequence in which the earliest of the Camposanto frescoes were executed came from the painting conservator Leonetto Tintori, when he was detaching the wall-paintings after the severe damage during World War II. He discovered from the way the walls had been prepared for painting and how the plaster of one mural overlapped the next, that the Crucifixion at the south end of the east corridor was painted first and by a different artist than the frescoes to either side (Fig. 3). Soon thereafter, a consistent but distinctive preparatory method was employed for the famous group of frescoes to the right in the south corridor and the other Christological scenes to the left in the east corridor.[8]

Fig. 3. Master of the Camposanto Crucifixion, Crucifixion, c. 1330-36, east wing, Camposanto, Pisa, present condition. (Photo: Geoffrey Hodgetts)

Architectural historians also helped to secure the dating of the frescoes, using the physical evidence of the building in combination with archival records to trace the gradual gestation of the Camposanto. As they contended, the cemetery originally took the form of a walled field with a mortuary church by about 1287, but by the 1320s, the church was demolished and roofed galleries were being constructed around the burial ground.[9] The date of a wall altar dedicated to All Saints (Ognissanti) revealed that the south side of the east corridor had been erected c. 1320-30, and that it was to decorate the wall behind the altar that the Crucifixion was painted, initially in isolation, c. 1330-36.[10] To the right and around the corner, the east side of the south corridor could be dated from the earliest wall tomb, commemorating the local hermit Giovanni Cini, who died in 1331.[11] For this investigation, Cini’s tomb is important because the Thebaid was painted right above the tomb just a few years later, and the tomb’s baldacchino extended upwards, covering part of the right side of the rectangular field on the wall.[12] In other words, the Crucifixion was completed first as part of a wall altar, and then the Thebaid was envisioned in direct association with a local hermit’s tomb and as part of a cycle of three frescoes.

In the following decades, the rest of the long south corridor was constructed and frescoed. Then, over the course of more than a century, the west and north corridors were built, and the north corridor was frescoed in two stages, first with the initial scenes from Genesis (Piero di Puccio, 1389-91), and much later, with a remarkable, extended cycle of Old Testament murals (Benozzo Gozzoli, 1468-84).[13] Yet when the Thebaid was being painted, one-hundred-and-fifty years before the decoration of the north corridor was finished, viewers would have had a very different experience. Construction was underway along the south corridor, but only the southeastern corner was roofed and being frescoed. For this study, an understanding of the unfinished state of the Camposanto is important since the interest is in the original conception of the Thebaid, not the way the fresco may have been received in later decades.[14]

The state of repair of the fresco also requires review because a history of severe damage and waves of restoration have left their mark on the pictorial surface. Already in the mid 16th century, Giorgio Vasari lamented the deterioration of the Camposanto frescoes, noting colour changes, areas where plaster was detaching, and that many of the inscriptions had been “obliterated”[15]. He ascribed the decay to the exposure of the walls in the open corridors and to the damp and saline atmosphere close to the ocean.[16] A substantial revision of the Thebaid took place in the late 14th century, when the wooden baldacchino that stood over Cini’s sarcophagus was removed. A large unpainted area of conical shape was exposed in the lower right portion of the fresco. To fill the space, Antonio Veneziano painted three monks seated in front of a monastery, and above them, a hermit sitting in a tree.[17] Much later, in the mid 17th century, Zaccaria Rondinosi repainted several areas, including, at the bottom in the centre, the monk whose bird feet exposed his demonic nature and, on the upper right, Antony lecturing two fleeing devils.[18]

Fig. 4. Buonamico Buffalmacco (attrib.), Thebaid. Detail showing large area of paint loss and exposure of straw matting, 11 September 1944. Photo by Major J. Bryan Ward-Perkins. (Photo: National Archives, RG 239-PA, College Park, MD)

In addition, the murals suffered acute damage during World War II, when, in the course of a prolonged artillery battle in July 1944, between American and German divisions across the Arno River at Pisa, shells from American positions hit the roof and started a fire that lasted for several hours. The heat altered the tonality of the paint surface, and when flames reached the preparatory layer of straw matting (incannicciato) under the lime plaster, sections of intonaco bubbled up and the attachment to the walls was undermined. A photograph taken about six weeks later shows a large paint loss in the Thebaid (Fig. 4). To preserve the pictorial layers, most of the frescoes and some portions of the sinopie were detached and mounted onto new supports. However, the permanent losses to the Buffalmacco cycle were substantial and included much of the border decoration with inscriptions.[19] In the case of the Thebaid, which was returned to its original location in the south corridor in 2014, the most obvious damage encompasses four large areas of paint loss on the upper level and sections in the lower right where the colours are faded or partially lost.

The Established Interpretation of the Thebaid

Before turning to the landscape, the accepted reading of the painting will be explained to clarify how the environmental perspective is quite different and to introduce the imagery in the fresco. What paved the way for the line of inquiry that concentrated on the hermits and their sequential representation was the recognition of the close relationship between the Thebaid and Domenico Cavalca’s Vite dei Santi Padri. The treatise was a collection of eremitical texts that the Dominican preacher, Cavalca, had translated into the volgare in Pisa in about 1330. As Salomone Morpurgo first noticed in 1899, the order in which the hermits appeared in the fresco, for the most part, followed the stories in Cavalca’s popular translation.[20] Discussion of the Thebaid and its connection to Cavalca’s treatise was revived in 1960, as part of a major publication to celebrate the completion of the restoration of the Camposanto and its wall-paintings after the war.[21]

Since the 1970s, the conception of the Thebaid as the artistic equivalent to a Dominican sermon has been explored. The fresco was “laced with texts”, some similar to tituli, in that they identified the subjects, while other longer inscriptions in verse summarized the stories.[22] Many of the inscriptions are no longer visible or only barely legible, but originally, despite the small size of the print, the words would have contributed to the exposition of meaning. Scholars associate the combined use of images and texts with the instructional tenor of Dominican preaching.[23] However, none of the inscriptions matches a passage in Cavalca’s compendium. Nevertheless, the hermits and the spiritual wisdom they offered had long been familiar to educated churchmen, since Latin manuscripts with groups of eremitical texts, known as the vitae patrum, had circulated for centuries.[24] These collections of stories kept the ordeals experienced by early holy men and women, and the desert environment in which their adventures unfolded, alive for readers in the late Middle Ages.

Moreover, beginning in the early 14th century, illustrated manuscripts of the Latin vitae patrum appeared. Although the most notable manuscripts were created in southern Italy and Sicily, probably in association with monastic houses, some scholars believe the new visual imagery was inspired by a widespread availability of Byzantine or Italo-Byzantine models in both southern and central Italy.[25] The Byzantine precedents, in turn, may have engendered larger pictorial images, such as the Thebaid in the Camposanto. In some cases, the new imagery served to invigorate the ancient stories of spiritual trials in distant deserts. Indeed, Denva Gallant suggested that the illuminations in the Sicilian Vitae patrum (Biblioteca Vaticana, MS Vat. Lat. 375, early 14th century) were designed to “recreate the [unyielding terrain of the] desert of the fourth century” as a symbol of the renunciation and denial undertaken by the hermits.[26]

But since the early hermits led such extraordinary lives in faraway lands, scholars believe that local preachers like Cavalca played the role of intermediaries by bringing the stories down to earth for their flock, many of whom were illiterate.[27] To make the hermits seem relevant, it is also thought that Dominican preachers drew attention to the rigorous devotions of more familiar holy people. A local example was the beato Giovanni Cini, who had lived as a recluse just outside the city and whose tomb was situated right below the fresco.[28] Chiara Frugoni has also suggested that, to reach a local audience, the river portrayed at the bottom of the fresco could have been reimagined as the Arno.[29] In this article, however, a different approach will be ventured, by considering how a landscape was created that captured the environment in Egypt where the early hermits undertook their arduous quests.

Scholars have also compared the fresco to a page in a manuscript, which the Trecento viewer would have read with the guidance of a friar or cleric, from top left to bottom right, proceeding along the three horizontal levels into which the composition was organized.[30] To create a painting of this nature, Buffalmacco would have been dependent on a learned advisor for the scenes of hermits and the inscriptions. Most likely, his advisor was a cleric at the cathedral, since the Camposanto fell under the control of the cathedral opera, but a local Dominican may also have been involved.

Fig. 5. Buonamico Buffalmacco (attrib.), Thebaid. Detail with two scenes of Paul and Antony, including mountains, caves, palm trees and lions. Present condition. (Photo: Geoffrey Hodgetts)

Fig. 6. Buonamico Buffalmacco (attrib.), Thebaid. Detail with Paphnutius covering Onuphrius’s body after death. Present condition. (Photo: Geoffrey Hodgetts)

Following this approach, scholars concentrate on the portraits of hermits and adjacent texts and the meaning emerges gradually. The reading would begin at the top, where scenes with Paul the Hermit, Antony and Hilarion appear in the sequence found in Cavalca’s treatise.[31] The primary message on this tier involves the exceptional resilience of Paul and Antony, who chose to live in isolation in remote reaches of the desert, and their achievement of spiritual enlightenment. In the middle zone, hermits who may have lived a generation or more after Paul and Antony are depicted, such as the wild ascetic Onuphrius in the Theban desert. The theme of the rewards of a saintly death, which is introduced in the top left corner with Antony’s careful burial of Paul, is continued here as Paphnutius attends to the body of Onuphrius upon his death (Figs 5 and 6). Further emphasizing the theme of death, there is a “memento mori” near the centre of the zone, in which Macarius of Egypt converses with the skull of a pagan high priest, who is suffering punishment by fire in hell because of his ignorance of God (Fig. 7).[32] On the bottom level, several younger monks, who are part of cenobitic communities, and two holy women are represented. They are shown living close to the river and, on the left, a walled city. The belief that cities were places of evil and sin pervaded early Christian writings.[33] For this reason, the dominant theme is the constant threat posed by worldly pleasures and demonic apparitions. One hermit resists a beautiful temptress by burning his hands in a fire.

Fig. 7. Buonamico Buffalmacco (attrib.), Thebaid. Detail with Macarius of Egypt conversing with a skull. Present condition. (Photo: Geoffrey Hodgetts)

Embarking on a Reading of the Thebaid that Prioritizes the Landscape

While not minimizing the importance of the established approach to the Thebaid, in which the meaning accrues gradually as the scenes of the hermits are “read” together with the adjacent inscriptions, beginning in the top lefthand corner, another trajectory will be proposed here. Since the Thebaid was positioned quite far above the pavement, to see the upper level would have required that the viewer step back as far as possible and tilt their head upwards. Arguably, it would have been more comfortable to enter the painted world at the bottom, closer to eye-level. In a similar way, the viewer is pulled into the Triumph of Death on the lower left, where the startled horses and their riders have come to a sudden halt in front of three decaying corpses. When the decorative border of the Thebaid was intact, the painted scene with its frame would have encouraged a quasi-Albertian experience, as if one were looking through an enormous, horizontal window into a landscape populated with hermits and natural and mythical creatures. Along the bottom of the scene, the river served as the dividing line between the frame, with trompe l’oeil angels holding scrolls, and the illusion of the natural setting. In creating the setting, not only had the artist organized the composition in three horizontal levels, but a spatial relationship had also been established among the levels that affected the viewing experience. On the bottom, the near side of the river was flush with the picture plane. Positioned close to eye-level, the lowest zone drew the viewer in, but then the stairways led the viewer up to the middle and top levels and also back in space. As a consequence, when the landscape becomes the focus of attention, a natural route of inquiry begins at the bottom and proceeds towards the top, rather than the reverse.

To assist in the interpretation of the landscape, both literary and pictorial precedents will be brought into the discussion. When considering the literary sources, other scholars have relied on passages from Cavalca’s Vite dei Santi Padri to explain the meaning of individual hermits. However, when the focus is turned to the landscape, Cavalca is not necessarily the most appropriate choice, since he depends for information about the Egyptian setting on much earlier, eye-witness accounts. Like other late medieval compilers and translators, he copied or paraphrased from the Latin compendia known as the vitae patrum.[34]

Cavalca’s relationship to the early accounts can be discerned by comparing how the cave of Paul of Thebes is pictured in Jerome’s Vita S. Pauli, written in the 370s, with Cavalca’s description.[35] Translated into English, Jerome’s account reads: “[Paul] found a rocky mountain, at the foot of which a cave of no great size was closed with a stone. When he had removed [the stone] … he noticed within a great hall, which, open to the sky, had been covered with the widespread branches of an old palm.”[36] Cavalca’s version, in English translation, runs as follows: “[Paul] found a beautiful cave closed with a stone, at the foot of a beautiful mountain, which was almost entirely rocky. Taking this stone from the mouth of the cave to investigate what was inside, … he found a large and spacious place with a beautiful palm tree, which extended its branches towards the sky through an opening in the mountain. The palm was so wide and extended its branches so much that it almost covered and occupied this entire place.”[37] It is clear that Cavalca has closely followed Jerome. Aside from translating the Latin into the volgare, Cavalca added the adjective “beautiful” three times, reorganized some clauses, and inserted a sentence at the end about the size of the palm tree. Both repetition and the addition of adjectives to ornament the plain original text were tools Cavalca employed to create an “oral” style of writing that would hold the attention of a lay audience.[38]

In short, even though Buffalmacco took direction from a learned churchman in Pisa, it is advisable for the analysis of the fresco’s setting to search out the primary sources, in which the language had sprung from a direct knowledge of the environment. As will emerge, other insights about the landscape may also be found in these early treatises.

Using the Life of Antony to Unlock the Meaning of the Thebaid

For this interpretation of the Thebaid, privileging the landscape, the primary source that will be used is the Vita Antonii (or Life of Antony). The Vita Antonii was written in Greek soon after Antony’s death in 356, and many attribute the biography, or at least a good part of it, to Athanasius.[39] Athanasius, who was made Archbishop of Alexandria in 326, is credited with considerable authority, both because he had met Antony and because he had lived for periods with hermits in the desert, when he was compelled to hide from his persecutors.[40]

Even though many hermits are depicted in the Thebaid, I have chosen Antony’s vita to guide the reading of the fresco for a few reasons. The Vita Antonii was the earliest writing to focus on monastic life in the Egyptian desert and was also enormously influential. As a consequence, Antony was revered as the “founding father” of the hermits. Another decisive factor is that Antony’s journey through the Egyptian landscape can be mapped onto the setting of the fresco, as will be explained. The choice to rely upon Antony’s vita to illuminate the Thebaid also involves the recognition that Buffalmacco’s fresco cycle as a whole is heavily indebted to literary sources. To explore Buffalmacco’s Inferno, for instance, it would be appropriate to draw upon Dante’s Inferno (composed 1304-8, in circulation by 1321), and to allow Dante as the poem’s narrator, and Virgil as Dante’s guide, to assist in fathoming the frescoed landscape of hell.[41] In a somewhat analogous way, Antony will chart the course in this exploration of the Thebaid. Antony’s road to enlightenment involved a progressive withdrawal, both physically and spiritually, away from civilization and into isolation in the desert. In this analysis, the hermit’s journey will be separated into three stages, which will be mapped onto the three distinctive levels of the Thebaid, starting at the bottom and then ascending to the middle and upper zones.

The First Stage of Antony’s Journey and the Bottom Level of the Thebaid

Although Antony is not shown in the bottom zone of the fresco, his experiences during the first stages of his journey can be connected with those of the holy men and women represented. More important for this study is that the landscape can be interpreted as resembling the area in Egypt where Antony resided before he went into the desert. Although Athanasius did not describe these locations in detail, his brief references can be supplemented because a large literature developed around Antony, and the geography of Egypt attracted interest beginning in the ancient world.

According to Athanasius, the first stage of Antony’s religious training began when he was twenty and lasted fifteen years. During this period, he resided in two locations that were both relatively close to the village where he had been born and not far from the Nile. In the 5th-century Ecclesiastical History by Sozomen, it is said that Antony came from Komá in Lower Egypt, a village about 75 km south of the beginning of the Delta and modern Cairo.[42] Initially he lived as a recluse for a year, just outside Komá, under the instruction of an old man who had been a hermit. Antony then moved further afield to a necropolis and, in a symbolic process of burial, he enclosed himself for about fourteen years in one of the underground tombs. In this dark, confined environment, he was repeatedly accosted by the devil, and in one of these violent encounters, Antony came close to death.[43]

In a manner characteristic of the early Christian texts, Athanasius provides little information on the necropolis, describing it simply as “the tombs” and the location as “[at] some distance from the village.”[44] The tombs that immediately come to mind are the Egyptian pyramid complexes near the ancient city of Memphis, east of the Nile in the desert plateau, about 18 km southeast of present day Cairo. However, this would have meant a trip of about 100 km for Antony, which seems unlikely since no journey was mentioned by Athanasius. But there were also later burial sites from the Graeco-Roman period. Although the largest necropolis from this era that has been discovered is much further south in Upper Egypt, a small Roman burial chamber from the 1st- 2nd centuries CE has been excavated near Saqqara, directly west of Memphis on the Nile.[45] The burial chamber was cut into the rock escarpment and a stairway with walls made of limestone blocks led down to the entrance gate. It is possible that Antony took up residence in a Roman catacomb of a similar kind. As will be shown, several aspects of these initial stages of Antony’s journey can be applied to the interpretation of the landscape on the bottom level of the Thebaid.

Fig. 8. Buonamico Buffalmacco (attrib.), Thebaid. Detail of lower and middle tiers showing river with fish and stone bridge. Present condition. (Photo: Geoffrey Hodgetts)

When adopting an environmental approach, the river can be read as the protagonist of the lower zone. In the foreground, a wide river that represents the Nile flows along most of the width of the fresco. Entering the painting from below, the viewer’s eyes focus first on the river and then move to the monks, holy women and animals (Fig. 8). If the viewer becomes interested in the very large fish in the river, they will be apt to wander both to the left and to the right since the fish are swimming in both directions. It is apparent that the river begins on the far right, but it is not possible to determine whether the artist depicted the river as descending from a source in the rocky landscape because this section was repainted by Rondinosi. The river courses in a horizontal direction until it divides roughly at the middle, and the right branch flows under the stone bridge and into the distance.

The river in the Thebaid will not be interpreted as a “Nilotic” river, which would be replete with specific symbols from early Christian prototypes, as manifest in Jacopo Torriti’s late 13th-century apse mosaics in Santa Maria Maggiore and San Giovanni in Laterano in Rome, where the rivers are believed to represent the “River of Life” (Revelation, 22:1).[46] Instead, the depiction of the river in the fresco will be seen as one of the main components in the evocation of the landscape in which the early hermits lived, under the direct or indirect influence of early Greek and later Byzantine written and pictorial sources, and ancient discussions of the geography of Egypt that were known in the late Middle Ages. Consequently, an examination of ancient, medieval and more recent sources on the Nile will facilitate this reading of the original meaning of the river.

The Nile was the life force that determined the development of human society in Egypt, or as Seneca put it: “it is in the Nile, as you are aware, that Egypt reposes all its hopes.”[47] Beginning with the roots of ancient Egyptian civilization in 3150 BCE, the fertile land in the Nile Valley and Delta was critical for the extraordinary kingdoms that lasted for three millennia until the beginning of Roman rule in 30 BCE.[48] Roman domination continued through the early centuries of Christianity and until the Muslim conquest in 646 CE. In Roman Egypt, centres of population, many of which were of ancient origin, were mostly situated close to the river, except for the port cities on the Mediterranean and the Red Sea.[49] This was because of the absolute necessity of fresh water and fertile land for human survival in what was otherwise an extremely dry environment with almost no rainfall. In the valley bordering the Nile, alluvial plains were created by the annual overflow of water that carried clay and silt. Having learned how to enhance the river’s potential, the Egyptians engaged in intensive agriculture. During the annual flooding, the drainage was controlled with the help of man-made basins, and canals and irrigation systems were constructed to enable the development of arable land further from the river.[50] In the Roman period, Egypt produced wheat in abundance with three crops per annum. Other major agricultural yields came from barley, legumes, grape vines and olives.[51] Large quantities of these agricultural products were sent down the river to the port of Alexandria, whence they were shipped to Rome, and later, north across the Mediterranean to the new imperial capital of Constantinople beginning in 330 CE. Indeed, for hundreds of years, Egypt served as the “breadbasket” of the Roman Empire.[52] The many references to bread as an essential source of nutrition in the lives of the desert fathers may be seen in light of the fact that wheat was the principal agricultural product of Egypt.

There is evidence in the Thebaid to suggest that Buffalmacco’s advisor had some knowledge of Egypt and the Nile, which would not have been unusual for an educated cleric. As will be argued, the goal on the bottom level of the fresco may have been to evoke the environment close to the Nile, where the fertility of the soil allowed certain plants to grow, for instance, deciduous trees. Similarly, the depiction of a walled town and of cenobites implies the presence of agriculture to permit the development of communities.

The subject of Ancient Egypt exerted a fascination for ancient and medieval writers. Several authors explained how essential the Nile was for the development of civilization in Egypt. In a climatic zone that was otherwise extremely dry, the annual flooding of the river’s banks ensured the presence of fertile plains. Egypt and the Nile were discussed in several popular encyclopaedias and the Egyptian landscape was featured in the eremitical literature. Herodotus, Seneca and Pliny the Elder all wrote with considerable knowledge about the Nile. Although complete texts of Herodotus and Seneca were not available until the humanist editions of the Renaissance, Pliny’s vast Natural History (77 CE for books 1-10) survived into the Middle Ages.[53] In the early Middle Ages, the Venerable Bede and Alcuin extracted information from a few chapters of Pliny. By the 9th-10th centuries, there were nearly complete manuscripts, and the whole treatise of thirty-seven books was in circulation in the 12th century.[54] Petrarch had access to the complete Natural History, and manuscripts have been documented in many late medieval libraries.[55] Of course, not all medieval encyclopaedists, even when they had a complete Pliny to hand, discussed information from Pliny about Egypt and the Nile. For example, although the 13th-century Dominican, Thomas de Cantimpré, acknowledged his debt to Pliny in his influential De natura rerum, Thomas did not include the regions of the earth, and, therefore, the geographical features of Africa were not covered.[56]

If Buffalmacco’s advisor was not conversant with Pliny, he may have read Solinus’s shorter and more popular compendium from the 3rd century CE, in which much of what Pliny had written about Egypt was repeated. Originally known as the De mirabilibus mundi, Solinus’s treatise typically was referred to as the Collectanea in the Middle Ages.[57]

In the Natural History, Pliny devoted a substantial chapter to the Nile, and in turn, some of Pliny’s discussion was reiterated by Solinus, but in a less well organized way due to the haphazard insertion of information from other sources.[58] In his chapter on the Nile, Pliny carefully weighed the opinions of several authorities before arriving at conclusions concerning the mysterious source of the river, its course through Upper and Lower Egypt, and the characteristics and mechanism of the annual flooding. It is now recognized that the flooding, which begins with the waters of the Nile rising dramatically in June and reaching their height in September, is the consequence of monsoon rains in the distant “highlands” region of Ethiopia, far southeast of the modern border between Egypt and Sudan.[59] Two normally gentle rivers in these highlands, the Blue Nile and Atbarah, become greatly enlarged, and the water flows quickly downstream, carrying sediment, filling the Nile and then prompting the overflowing of the riverbanks. However, in Pliny’s day, several explanations had been proposed, and most writers supported the theory that the power of the sun was responsible, alternately drying up the river by its heat or, when its heat was diminished, allowing the river to overflow. Nevertheless, Pliny admitted that he found other ideas more convincing, one being that the Nile’s “waters are swollen by the summer rains of Aethiopia.”[60] On the other hand, Solinus, after acknowledging the “variety” of explanations, sided with the most popular theory that “the Nile’s flooding is completely drawn from the sun.”[61]

Pliny and Solinus also consider how the flooding of the Nile is essential to the practice of agriculture in Egypt. Pliny reveals his understanding that fertile soil results from the flooding when he describes the Nile metaphorically as “performing the duties of the husbandman [or farmer].”[62] Pliny includes information on how Egyptian farmers work in harmony with the rhythm of the floods: “When the waters have reached their greatest height, the people open the embankments and admit them to the lands. As each district is left by the waters, the business of sowing commences.”[63] Although Solinus does not provide as clear a summary of the relationship between farming and the Nile floods, he notes that the amount and duration of the flooding each year determine the “fertility” of the soil and the timing of “tillage”, and he gives the height in cubits that the Nile must reach to ensure a “successful harvest” as opposed to a “famine.”[64]

Therefore, both Pliny and Solinus discussed the distinctive characteristics of the Nile, particularly how the annual flooding resulted in the alluvial plains of the Nile Valley. Since both treatises circulated widely in the late Middle Ages, it is possible that Buffalmacco’s advisor was familiar with one of them. An understanding of the fertility of the soil in proximity to the Nile may underlie the representation of the river landscape in the Thebaid, which is more lush than the desert above. In addition to deciduous trees, several domesticated animals are represented: two donkeys or mules, a horse and a camel (Fig. 9). The inclusion of the camel is one of several indications of the influence of Byzantine pictorial sources, a topic to be considered below. The species that Buffalmacco painted was the one-humped dromedary, which was native to northern Africa, the Levant and Persia. As a group, the presence of the pack animals seems to imply fertile soil close to the Nile, since their fodder and the grain they carried on their backs were grown on arable land.[65] To symbolize the abundance of food, the river was also shown as full of fish. Evidently, the fish provide sustenance for local monasteries, since two tonsured monks are shown fishing.

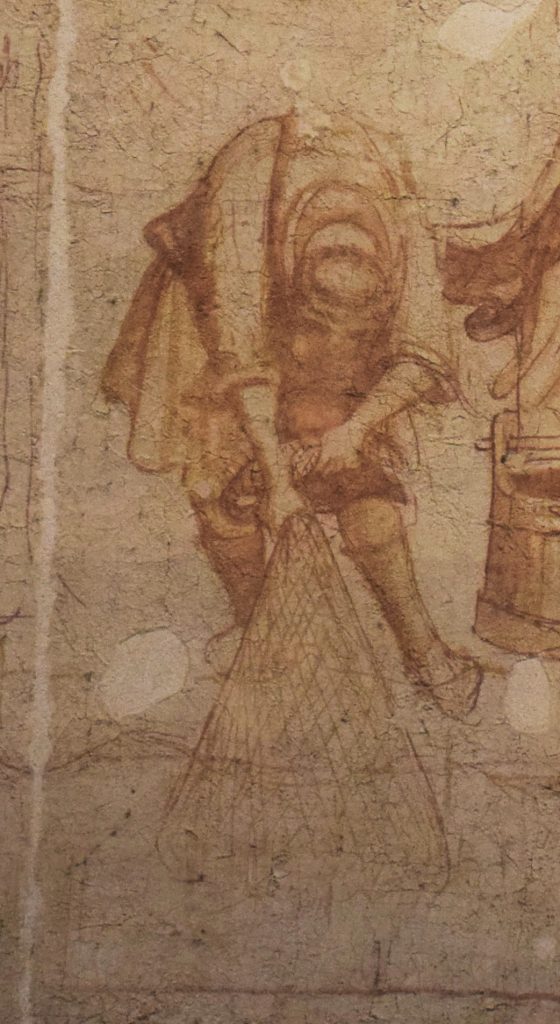

Fig. 9. Buonamico Buffalmacco (attrib.), Thebaid. Detail of monk with camel approaching city gate, and monk with fishing net. Present condition. (Photo: Geoffrey Hodgetts)

Fig. 10. Buonamico Buffalmacco (attrib.), sinopia of Thebaid. Detail of monk fishing with a net. Museo delle Sinopie, Pisa. (Photo: Geoffrey Hodgetts)

It is interesting that different fishing techniques are represented. The monk sitting beside the bridge has cast his line from a wooden fishing rod, and to the left, a young monk leans forward to gather in a fishing net with his catch (Fig. 9). The sinopia or underdrawing, which was detached from the wall during the post-war restoration, reveals the care that the artist took, using the geometric form of a cone to position the strings of twine so that they trace out the volume of the net (Fig. 10). Since the subject of the fresco ultimately derives from early Greek and Byzantine treatises, it is possible that Buffalmacco was influenced by Byzantine sources or close Italian copies when he represented the monks fishing. These precedents may also help to explain why some elements of the natural world are depicted in a stylized manner, even while the fishing net is rendered in perspective.

Two ancient Greek treatises that discussed fishing were very popular during the Byzantine era. Oppian’s Halieutica (or “Fishing Matters”), c. 177-80 CE, was an extended poem on the cunning nature of creatures of the sea and how to catch them.[66] The Cynegetica (or “Hunting Matters”), written in imitation of Oppian, c. 212-17 CE, was a similar poem about hunting land animals, in which fishing was briefly mentioned as a less dangerous activity than hunting.[67] Yet despite their widespread influence, only one Byzantine illuminated manuscript has survived, Biblioteca Marciana, Venice, MS Gr. Z. 479, which is believed to have issued from an imperial scriptorium in Constantinople c. 1000-10.[68] The text of the manuscript is the Cynegetica and most of the images accord with the content on hunting, but two that show anglers may have filtered in from a Byzantine manuscript of Oppian’s poem on fishing that is now lost. One of these shows a man standing by the water with a rod in each hand (fol. 2r), and in another, a fisherman hauls in a net similar to the one in the Thebaid, though he is standing in a boat not on shore (fol. 59r).[69] In both the Thebaid and the Marciana manuscript, the net takes the form of a large, cone-shaped sack, and the monk and fisherman haul in the catch by holding onto and pulling in the bundle of ropes. In contrast, in Duccio’s Calling of the Apostles Peter and Andrew from the Maestà (1308-11), in which the activity of fishing carries the early Christian symbolism of the apostles as “fishers of men”, Peter and Andrew hold four cords that are attached to the corners of a net in the form of a mesh bag.[70]

Yet even though fishing was of great importance in Egypt, especially in the Nile Delta, the early eremitical treatises, some of which discuss the cenobitic monasteries near the Delta, including Nitria, do not refer to hermits fishing.[71] However, the evidence suggests that there were originally Byzantine depictions of monks fishing, and perhaps Buffalmacco’s imagery was influenced by a Byzantine source or an Italian copy. Indeed, a monk is shown fishing with a rod in the lower right section of The Death of St. Ephraim and Scenes from the Lives of the Hermits (National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh), which forms the central panel of a tabernacle and is attributed to a central Italian artist c. 1280-90.[72] The numerous portrayals of hermits in the panel, some shown as anchorites in caves in the mountains, reveal a Byzantine derivation. Since this painting is from central Italy about fifty years before the Thebaid, it is possible that Buffalmacco, similarly, was influenced by Byzantine or Italo-Byzantine sources. The stylized depictions of fish in the river in the Thebaid, which are overly large and swimming close to or right on the surface of the water, also may reveal a Byzantine prototype. In the Marciana Cynegetica (fol. 59r), the same stylization occurs for fish in rivers and lakes. This manner of depicting swimming fish also appears in the Latin Vitae patrum from the early 14th century in Sicily (Bibl. Vat., MS Vat. Lat. 375, fol. 54v), for which the artist relied closely on a Byzantine model.[73]

A final characteristic of the river in the Thebaid that invites further analysis is the fact that it splits into two channels, with one branch continuing in a horizontal direction while the other turns right, flows under the bridge and disappears. A passage from Pliny’s Natural History suggests that the artist possibly was depicting the point downstream where the Nile spread out before draining into the Mediterranean and where silt was deposited to form the Delta. Some Greek and Roman writers correctly described the Nile as splitting into seven distributaries, but Pliny said that the Nile divided “into two channels.”[74] Therefore, in addition to evoking the fertility of the river valley, it is possible that the region of the Nile Delta was suggested.

Significantly, the Nile Delta and the valley south of the Delta were associated with the cenobites. Several of the hermitages in these regions were described in two travelogues that were well known in the Middle Ages.[75] The earliest was the Historia Monachorum in Aegypto, c. 395-96, which was written by an unnamed monk from the monastery established by Rufinus of Aquileia on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem. In diary form, a pilgrimage is described, undertaken by the author and brother monks to visit cenobitic and desert communities in 394-95.[76] Among the places they visited were the large city of Oxyrhynchus, about 200 km south of the Delta, the monastery that Antony had founded on Mount Pispir, and the celebrated monastic centre of Nitria, on the western edge of the Delta, southwest of Alexandria.[77] When Rufinus translated the travelogue from Greek into Latin a few years later, he also rewrote passages on particular hermits and monasteries, drawing on his own experiences and emphasizing aspects of Christian theology and the monastic movement. For instance, he had met Macarius of Egypt, who founded a complex of monasteries south of Alexandria at Scetis, and who was depicted in the Thebaid, conversing with a skull.[78] A second influential travelogue, known as the Book of Paradise or Lausiac History, was written in 419-20 by the monk Palladius, who was also from the Mount of Olives.[79] Palladius travelled widely in Egypt, Palestine and Syria, and visited many monasteries, some of which were near Alexandria, on the coast west of the Delta.[80] For periods, Palladius stayed in hermitages and he also tried to survive alone in the desert. Thousands of monks lived at the sites in Lower and Upper Egypt that Palladius visited, among them, the hermits Dorotheos and Didymus, who were friends of Antony.[81]

On the lower tier of the fresco, stories of holy men and women are staged in the setting of the Nile Valley. This region is represented as being busier and more “built up” than the middle and upper zones. Sometimes, the artist, even though an Egyptian landscape was being evoked, fell back on familiar local models for the representation of the architecture, such as showing a town with crenelated walls and an entrance gate with a tower, and a church with a rose window (Fig. 2). The monastery to the right of the stone bridge cannot be included in this discussion because it was added by Antonio Veneziano in the late 14th century. Nevertheless, it is apparent that there are monastic communities in the lush valley, and that they are living in proximity to an urban centre. In Egypt, many early hermitages rose up close to, on the edge of, and even inside towns. For example, there was an enormous community at Oxyrhynchus. Indeed, Rufinus described the city as overflowing with holy men and women.[82] As many as five thousand monks lived inside the city and about the same number lived outside the walls. Oxyrhynchus was not on the Nile but was able to support a large population because of a long canal, “Joseph’s Waterway”, that had been built to connect the Nile with Lake Moeris and the Fayum oasis to the west.

As suggested, the location of the cenobites close to the town in the Thebaid is significant. In early Christian writings, even though many monks lived in or close to cities, urban life was associated with the sins of the flesh, and it is temptations of this kind that some of the men and women in this zone of the fresco are confronting. Even though Antony is not among them, his early years as a recluse in the region south of the Delta are characterized in terms of a strenuous fight against vice.[83] The river landscape in the fresco may suggest that life here was much easier than in the desert. But when Antony’s spiritual endeavour is mapped onto the setting, less evident layers of meaning can be deciphered. In an environment that is fertile but close to cities, the monks and holy women experience the challenge of forbidden pleasures, and like Antony, must demonstrate that they are strong enough to ascend to the next level.

The Second Stage of Antony’s Journey and the Middle Level of the Thebaid

In the course of his spiritual quest, Antony left the necropolis in about 286 when he was 35, and moved to, what Athanasius described as, a “deserted fortress”, where he stayed for twenty years.[84] Athanasius tells us little about the situation of the dilapidated fortress, except to say that it was “beyond the river”, and to coin the allegorical title, the “outer mountain.”[85] If it was beyond the river, then it was east of the Nile, in the Eastern or Theban Desert. Early church historians have identified the site as Mount Pispir, which is close to the village of Dayr al-Maymūn. It would have been a journey of about 10-15 km, the way the crow flies, from Komá, where Antony was born, though he would have had to cross the Nile.

Presumably it was in a Roman fort that Antony lived on Mount Pispir. Under the Romans, numerous military forts, some of them small and known as praesidia, were built in the Eastern Desert along the caravan routes from the Nile to the Red Sea. The primary purpose of the forts was to allow the Romans to control traffic and collect taxes, but they also served as watering stations because there were wells. Some of the Roman forts and “fortlets” have been excavated and many more are known to have existed.[86]

Mount Pispir was in the northern part of the Theban Desert. The original name of the desert to the east of the Nile, the Thebais, came from the ancient capital of Upper Egypt, Thebes, which grew up in the valley to either side of the river and today lies within the limits of modern Luxor. To the east of the river and beyond the fertile valley was the vast desert, which had a different geological character in its northern (or lower) and southern (or upper) regions, with the dividing line falling roughly at Qena near Thebes. The fort in which Antony lived was in the Lower Theban Desert, where the terrain was formed from a limestone plateau.[87] As was the nature of limestone, there were underground streams that sometimes came to the surface in pools of water. The dramatic landscape featured rolling hills, mountainous cliffs, and in between, deep valleys with dry riverbeds, called wadis (sing. wadi) in Arabic. Although the annual precipitation was extremely low and, in some years, there was no rain at all, the riverbeds could hold water after an occasional and unpredictable heavy rain event and then the wadis became tributaries that drained into the Nile or the Red Sea.[88]

Antony’s journey to Mount Pispir, within the limestone plateau of the Lower Thebais but not far from the Nile, would have taken him away from the fertile valley and up into an arid and mountainous environment. In an analogous way, to transition from the bottom to the middle level in the Thebaid, the movement is away from the river and its lush landscape and upwards with the help of steps that are cut into the bare cliffs. Two diagonal paths are represented. On the left, behind the young monk who is fishing with a net, jagged steps lead up to a hermit’s cell, where a demon disguised as an elderly pilgrim is trying to lead the hermit astray (Fig. 8). A second and longer series of steps begins to the left of the stone bridge and ascends towards a cave where an ill-omened encounter is taking place between the monk Macarius the Roman and a richly dressed woman, whose clawed feet expose her evil nature (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11. Buonamico Buffalmacco (attrib.), Thebaid. Detail showing staircases from lower to middle level and from middle to upper level. Present condition. (Photo: Geoffrey Hodgetts)

The fort where Antony lived on Mount Pispir was close to the river, whereas his later home would be in a more remote part of the Thebais. To evoke a similar progression in stages towards increasing isolation and a more desolate landscape, the artist suggested that the middle level was a transitional environment between the fertile realm at the bottom and the mountainous desert above. This was achieved by the insertion of representative features. To indicate fertile areas, fruit trees are depicted and olive trees with their thin, greyish leaves. In contrast, the plateau on the far right, where Paphnutius covers the dead body of Onuphrius, appears to be rocky and barren (Fig. 6). The dwellings of the hermits also suggest a transitional stage since there are buildings like those on the bottom level but also caves in the cliffs. Just as Antony spent many years in isolation at the mountain fort, similarly, anchorites are shown living on their own. Their trials were captured in the early Christian travelogues and later in the Latin vitae patrum and Cavalca’s Vite. In the fresco, the elderly Macarius the Roman epitomizes this physical struggle as he has nothing to cover his nudity save his long, white tresses (Fig. 8).

However, despite two decades of unimaginable deprivation, Antony miraculously emerged from the fort with a strong and youthful physique.[89] The health of his body was symbolic of deeper changes, since the reborn Antony manifested an inner peace and wisdom. As a result, many were drawn to him, and as the “cells multiplied”, a monastic community sprung up.[90] To characterize this new community, Athanasius uses poetic language in which landscape serves an allegorical purpose. First, he inserts verses from Hebrew scripture to suggest that, in spite of the desert, the monks are experiencing a paradisal environment: “How lovely are your dwellings, Jacob, and your tents, Israel; like shady groves, and like a garden by a river, and like tents which the Lord pitched, and like cedars beside the waters.”[91] Expanding on the contradictions between the actual landscape and the realm of inner experience, Athanasius claims that: “there were monasteries in the mountains and the desert was made a city by monks.”[92] He uses an oxymoron to emphasize the difference between the geographic environment and the spiritual plain on which the hermits exist. Large communities, such as a monastery and a city, cannot survive in the hostile desert or its mountainous regions. The poetic images of landscapes in the scriptural verses and the oxymoron suggest the different kind of society that the monks have created, which is no longer rife with temptation, but has been purified through their collective spiritual endeavour to enter the gates of the City of God. If the landscape of the middle zone of the fresco is more fertile than would be the reality on Mount Pispir, it is possible that, inspired by these passages from the Vita Antonii, the green foliage and deciduous trees have symbolic meaning (Fig. 11).

The Third Stage of Antony’s Journey and the Upper Level of the Thebaid

Yet as time passed, Antony sought more extreme isolation so that he could be free from interruptions to pursue his spiritual discipline and prayer. Therefore, he moved much further into the desert to his “inner mountain” and permanent resting place, only allowing himself to be drawn away, back to the hermitage on Mount Pispir or into Alexandria, when the need was great.[93]

It was Antony’s plan, as Athanasius explained, to travel into the Upper Theban Desert, but while he sat waiting for a boat to cross the Nile, a voice urged him to join a group of Saracens on their way across the Lower Desert to the Red Sea.[94] Even though Athanasius only tells the reader that they journeyed for “three days and three nights”, this may have been an invitation to follow Antony along one of the long-familiar pathways through the desert. Trade routes had been developed in Ancient Egypt from cities on the Nile to the Red Sea. Rest-stops at oases with wells were essential to survival in the desert and they were normally positioned so that caravans could stop every two days along the road. Pliny discussed these watering holes, many of which were fortified into official stations by the Romans in the 1st- 2nd centuries, and known as hydreumata (sing. hydreuma).[95] Because these paths across the desert were actively used for more than a thousand years, it is likely that, in Antony’s day, the routes were recorded in written or graphic form. In addition, regular travellers, among them monks, would have communicated to others the essential facts on the topography of the Thebais, including the wadis. Athanasius’s early Christian readers knew about the routes across the desert and, therefore, it may have sufficed to relate only the beginning and end points and the duration of the journey. For this analysis, however, more details will assist in tracing Antony’s journey and interpreting the Camposanto fresco.

To reach the “inner mountain”, which church historians have identified as Mount Colzim, Antony and the Saracens would have walked along a natural ravine formed by dry riverbeds. It is likely that they took the Wadi Araba, which originated close to the Nile and ran eastwards as far as the present-day village of Zaafarana on the Red Sea coast.[96] Antony travelled with the caravan for about 150 km, until they came to a “very high hill”, where he stopped. Athanasius described how Antony “fell in love” with the place that had been chosen as his final retreat by God.[97] Situated in the northern foothills of the Red Sea Mountains, a ridge of hills and mountains that separates the desert from the narrow coastal plain, Mount Colzim is about 30 km from the sea. There are monastic caves in the cliff face and the one in which Antony is believed to have lived is 680 m above sea level.[98] When describing the perfection of the “inner mountain”, Athanasius mentions a nearby spring, with “water – perfectly clear, sweet and quite cold”, and still today, several fresh water springs emerge from the limestone cliffs.[99] For his sustenance, Antony ate bread that was initially supplied by the Saracens and later by his disciples from Mount Pispir. He also received nourishment from “a few untended date palms”, and after tilling an area of suitable land nearby, Antony grew grain so that he could make his own bread.[100] Later, to offer refreshment to visitors who had made the arduous journey, Antony “planted a few vegetables.”[101] Athanasius records that wild animals were attracted to the fresh water and approached Antony’s farm, but the holy man was able, through the power of God, to persuade them to keep their distance and to tame them.[102]

As scholars have recognized, when Antony is accorded the ability to transform the infertile soil of the escarpment into a field of grain and a market garden, and to pacify dangerous animals like lions, there are allusions to Job, who lived in harmony with the beasts, and to Adam.[103] In Paradise, Adam took care of God’s always fruitful garden, but after the Fall, he struggled to grow food for his family in hard, rocky soil that yielded only thorns and thistles.[104] Antony is portrayed as a “new Adam” because he overcomes the obstacles of the fallen world by creating a garden in the desert. The transformation of the soil from barren to fertile symbolizes Antony’s harmonious relationship with God and His creation.[105] Just as the landscape plays a central role in Antony’s spiritual achievement, so too, in the fresco, the painted world can be interpreted as having allegorical meaning, as an exploration of the upper realm will reveal.

To gain the summit, the viewer must climb up the cliffs, as Antony does when he reaches the Red Sea Mountains to find his cave far up the slope. Two paths in the fresco invite this ascent, a long, winding staircase in the centre and a shorter series of steps on the far right (Fig. 11). In each case, the viewer is led to an isolated cave. In the central cave, Antony is seen carving a wooden spoon, a meditative activity associated with the hermits. On the far right, a hermit, who may represent Antony in old age, is reading scripture.

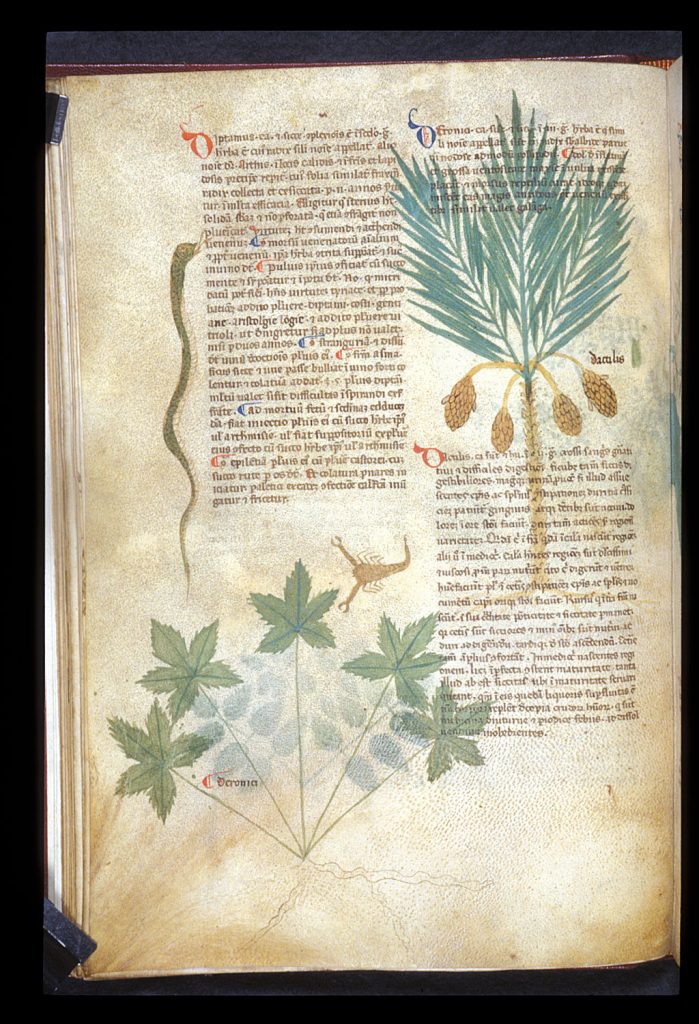

The dominant characteristic of the painted landscape is the mountain ridge with barren and craggy peaks that denote a remote and infertile environment. Five mountains are distributed across the foreground and a sixth is almost hidden in the distance on the right. Each of the foreground mountains is punctuated by a cave, providing a natural cell for a hermit, but two stone chapels are also shown. On the left, the first two caves act as the settings for the culminating events from Paul’s vita (Fig. 5). As mentioned, Jerome had described a large palm tree that was growing inside Paul’s cave, with the palm branches forming a natural roof, and Cavalca had closely followed Jerome. In the fresco, Buffalmacco includes the palm in each representation of Paul’s cave, but he positions the tree outside and just to the right of the cave, not inside. It would have been difficult to depict the meeting of Paul and Antony inside the cave together with a large palm tree. Buffalmacco’s choice of placement for the palm also seems to accord with the Byzantine tradition and with Italian manuscripts that were heavily dependent on Byzantine models. For instance, the same configuration is found for anchorites that are shown with a cave and a tree, sometimes a palm, in the Vitae patrum from the early 14th century in Sicily (Bibl. Vat., MS Vat. Lat. 375, fol. 124r) and in a Vitae patrum created in Naples, c. 1336 (Morgan Library, New York, MS M.626, fol. 3r).[106]

The palm plays a significant role in the representation of Paul and his remote dwelling in the fresco. On a symbolic level, the date palm, which carries rich meaning in Hebrew and Christian scripture, may allude to Paul’s future in Paradise, and from an environmental perspective, the tree indicates that distinctive plants are native to the upper zone of the landscape in the Thebaid.[107] Similarly, the lions in the second scene can be read as contributing on several levels to the meaning of the fresco. Literally, they are part of Jerome’s story, in which two lions helped Antony to bury Paul, but the lions also further the religious allegory as evidence of Antony’s God-given ability to tame wild animals. Additionally, in the context of the landscape, the lions help to evoke the desert wilderness.

Fig. 12. “Phoenix dactylifera”, Tractatus de herbis, Southern Italy, c. 1300, British Library, Egerton MS 747, fol. 33v. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Given the importance of the palm tree, the question of why Buffalmacco departs in this instance from the Byzantine pictorial tradition is worthy of attention. The standard type, which can be traced back to the Greek materia medica codices of Dioscorides, was known in Italy since it appears in a range of Italian manuscripts from the 14th century. These include a southern Italian herbal, the Tractatus de herbis, c. 1300 (British Library, London, Egerton MS 747, fol. 33v, “Phoenix dactylifera”) (Fig. 12), and the Vitae patrum manuscripts from Sicily and Naples introduced above (Bibl. Vat., MS Vat. Lat. 375, fols 21v and 124r; and Morgan Library, MS M.626, fol. 87v).[108] The primary characteristics of the date palm in these standard depictions are the palm fronds that fan out at the top of the tree, the distinctive “pseudobark” of the trunk, which is formed from dried-out tissue after the fronds fall off, and the clusters of brown dates that hang from the top of the trunk, below the green fronds. Buffalmacco features the palm fronds at the top but represents the trunk as having smooth bark and does not include the dates. The sinopie for the areas to the right of each cave have not survived to enable an examination of the preparatory drawings for the palm trees. It is possible that the trunks were repainted during one of the restorations of the fresco, or that, for some other reason, Buffalmacco did not follow the Byzantine formula. The palm trees that the artist could have seen in Italy, where they have been grown since ancient times, would not have had the hanging fruit, since the Italian climate is not hot enough.

In the upper realm of the fresco, however, the most significant elements of the scenery are the mountains, which act as the defining characteristic of the zone (Fig. 5). Carrying both literary and symbolic meaning, the mountains signal the lofty regions of the desert to which Paul and Antony retreated, and because of their height, they also symbolize the hermits’s spiritual achievements. Therefore, it is important to recognize that the mode of representation in the fresco includes both stylized and naturalistic aspects. Regarding artifice, the distortions in scale are obvious, as the mountains are sufficiently diminutive to frame the scenes with hermits. On the other hand, naturalism is involved, since details of the depiction suggest that an actual site is being reproduced, even if topographical precision was not Buffalmacco’s intention.

Each mountain is roughly conical in shape and is built up from layers with jagged surfaces. One could mistake these shapes for stylized, artistic forms, but once the story of Antony and the mountain ridge in the Lower Thebais is projected onto the reading of the fresco, it is possible to detect in the peaks a resemblance to the structure of limestone outcroppings. It may be helpful to understand the process through which limestone mountain ridges were created over the ages of geological time. In shallow water, sedimentary layers of carbonate rock originally formed into limestone in continental shelves, but much later the limestone became exposed as the oceans retreated. These outcroppings were then gradually eroded by rainwater, wind and sand, and as part of the erosion, gorges and systems of caves were formed. The dramatic topography that results is called “karst” by geologists.[109] Because the mountains are originally the product of sedimentation and then are eroded, they appear to be mounded up from many irregular layers into strange shapes with caves. In the Thebaid, some of the essential features of the Red Sea hills and mountains are captured since the form of each mountain suggests a cumulative layering process and there are caves.[110]

Although the sections of the Arno River Valley between Florence and Pisa feature complex geological formations involving sedimentary rocks, primarily sandstones, the principal “karst” landscapes in Italy are in the limestone Dolomites in the Alto Adige. In this article, however, instead of suggesting that a landscape is being depicted that is familiar to viewers in Pisa, close to the Arno, a case is being built for Buffalmacco’s reliance on Byzantine sources, either directly or indirectly, to evoke an environment that was fundamental to the hermits and eremitical literature. Joseph Polzer connected the mountains in the Thebaid to depictions of rocky landscapes in Byzantine mural paintings and manuscripts, such as an 11th-century, Greek manuscript of John Climacus’s Scala paradisi (Princeton University Library, MS Garrett 16, dated 1081), and the previously introduced Latin Vitae patrum from Sicily and now in the Vatican.[111] In the Vatican Vitae patrum, on fol. 18r, the colouring of the mountains in brownish-yellow or greyish-green, can be compared with the Thebaid, where the peaks are represented either using yellow earth or green earth pigments. However, the hermits’s caves in the mountains in both the Princeton Scala paradisi (fol. 66v) and the Vatican Vitae patrum (fols 18v, 48r and 49r) are more stylized than in the Thebaid. In the Vatican manuscript, some of the cave entrances are decorative, with a lacey pattern, and in the Princeton manuscript, the simplified oval form of the entryway does not resemble the cavernous openings in limestone outcroppings.[112]

It can be concluded that Buffalmacco’s mountains were derived from a Byzantine prototype, though one that was closer to the Vatican Vitae patrum, created in the early 14th century in Sicily under heavy Byzantine influence, than to the 11th-century, Greek manuscript in Princeton. Originally, the manner of representing the mountains with their caves would have been established in early eremitical codices, illustrated by monks who were familiar with the desert landscape, and then the illuminated manuscripts were copied and recopied over the centuries. For the mountains, Buffalmacco, whether intentionally or by accident, imparted an authentic look of limestone outcroppings in the Lower Thebais. At the same time, when read allegorically, the peaks acted as symbols of the spiritual heights that Paul and Antony had reached.

Concluding Thoughts

When the elaborate landscape in the Thebaid is subject to scrutiny, it becomes apparent that the setting can be divided roughly into three tiered zones and that steps cut into the rock cliffs allow transitions between the levels. The artist seems to have used a form of shorthand to represent the environment of each zone by inserting a few topographical features, most obviously the river to signal the fertility of the lower level and the barren mountains to indicate the altitude and arid climate of the upper tier. As this study has suggested, it is also fruitful to investigate the landscape in relation to the Vita Antonii. Indeed, the places where Antony resided in Egypt, during the stages of his retreat from the world into isolation, seem to match the painted zones. By closely associating Antony’s journey with the terraced landscape, the levels of meaning in the fresco can be apprehended. Whereas the literary approach often taken to the Thebaid entails reading the small figural compositions and accompanying inscriptions to accumulate meaning, in this article, clues have been gathered from the landscape with the help of Antony’s vita.

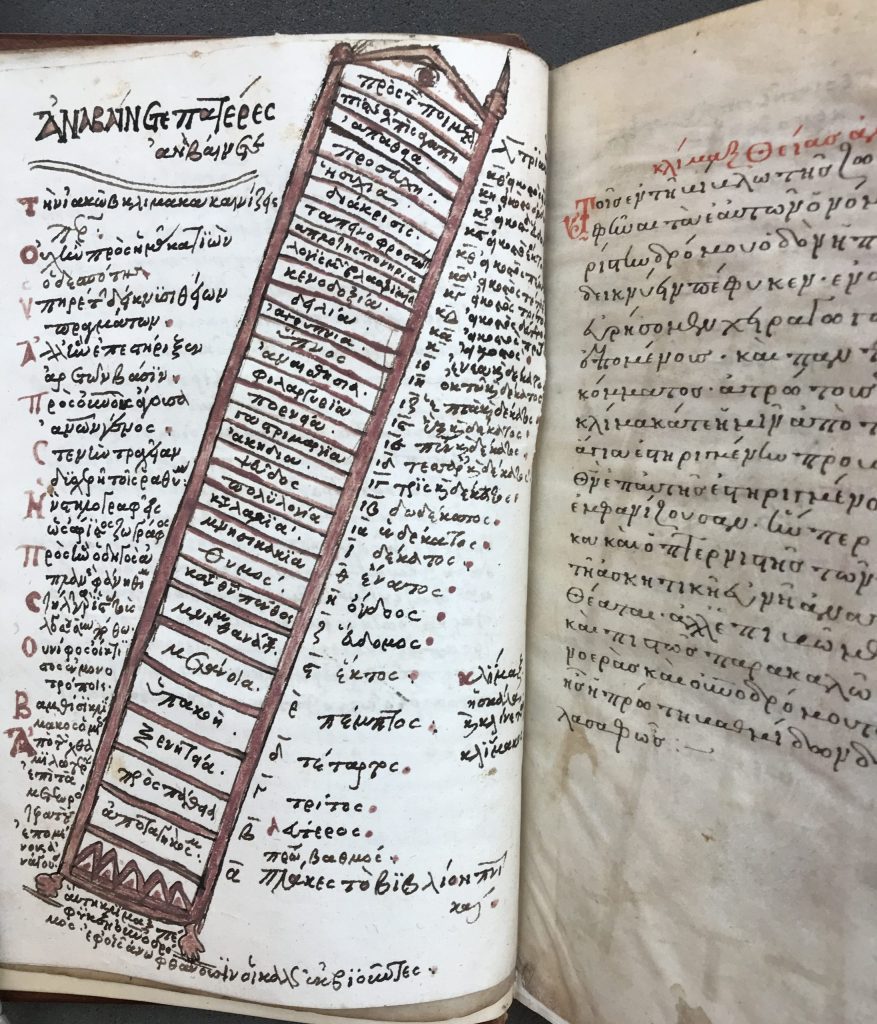

One consequence of prioritizing the landscape alongside the biography of Antony is that the allegorical significance is uncovered. This is most obvious when the steps in the rock cliffs, which have to be climbed to reach the top, are recognized as a traditional Christian symbol. The symbolic meaning of this “perilous ascent to God” was elucidated in Adolf Katzenellenbogen’s classic study of the virtues and the vices in medieval art.[113] Katzenellenbogen explained that the struggle within the human soul was originally envisioned as a war between the virtues and vices in Prudentius’s Psychomachia (early 5th century). Subsequently, however, first Greek and then Latin theologians adopted the metaphor of the soul climbing a ladder to God, taking inspiration from Jacob’s dream of a stairway to heaven (Genesis, 28:10-15) and Moses’s ascent of Mount Sinai (Exodus, 24: 9-18).

Fig. 13. Byzantine, John Climacus, Scala paradisi, 13th century, University of Oxford, Bodleian Libraries, MS Holkham Gr. 52, fol. 3v. (Photo: Cathleen Hoeniger, courtesy of the Bodleian Libraries)

The metaphor is explicit in the Scala paradisi (or Ladder of Divine Ascent), which was written in about 600 by John Climacus, abbot of a monastery on Mount Sinai, to offer guidance for local monks. Climacus compared the otherwise abstract process of progressive renunciation and prayer to the concrete activity of mounting the thirty rungs of a ladder, and he clearly articulated the Christian nature of the ascent.[114] The famous codices of the Scala paradisi from the 11th and 12th centuries at St. Catherine’s Monastery, Mount Sinai, feature illuminations of the ladder with holy men ascending to Christ and demons trying to pull them off.[115] In some manuscripts, however, a more simple diagram of the ladder is included, with short titles to characterize each step, for example, Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, MS Holkham Gr. 52, 13th century, fol. 3v (Fig. 13). But because the Scala paradisi was only translated from Greek into Latin by the Franciscan dissident Angelo Clareno in about 1300-20, it is not certain that Buffalmacco’s advisor would have known the treatise.[116] More likely, the symbol was circulated in Bonaventure’s Itinerarium mentis in deum (c. 1259), in which a ladder with six rungs is used to picture the journey towards God. Bonaventure acknowledges his debt to another Greek work, De mystica theologia, by the neo-platonist Pseudo-Dionysius (late 5th-6th century), where the means of reaching God is described as abandoning everything of this world and ascending inwards through darkness and void towards the divine realm.[117] How prevalent the symbolism had become by the time Buffalmacco painted the Thebaid is demonstrated by Dante’s use of a golden ladder or stairway, “stretching beyond the reaches of my sight”, in Paradiso, canto 21.[118]

Yet rather than representing the ladder and its Christian message in an explicit way, the fresco is more subtle. The terraced landscape with distinctive environmental zones and with steps in the cliffs implies an ascent from one level to the next. Groups of desert fathers and mothers reside in each of the zones and exemplify to varying degrees the struggle against vice and the acquisition of virtue. On the top level, Paul and Antony represent the highest level of spiritual achievement and, therefore, offer mentorship for the final ascent. Although the Christian nature of the climb is not underlined, it is important to remember that, when the Thebaid was originally painted, the enormous fresco of the Crucifixion had just been completed around the corner (Fig. 3). The adjacent image of Christ on the Cross would have reinforced the fact that the rigorous climb built into the landscape of the Thebaid was a form of imitatio Christi, and that the goal, at the top of the spiritual staircase, was Christ.

Fig. 14. Buonamico Buffalmacco (attrib.), Thebaid. Detail with Antony’s vision of Christ. Present condition. (Photo: Geoffrey Hodgetts)

When Antony is taken as guide for the journey through the Thebaid, the dual nature of the landscape becomes evident. The zones are both geographical and allegorical, just as Antony’s journey is not only a physical trek but also a spiritual one. Eventually, the top zone is reached, with jagged peaks that bring to mind the limestone outcroppings in the Thebais, the place where Antony found his “inner mountain.” As described in the vita, after reaching Mount Colzim, Antony demonstrated Christ-like powers through miraculous healings and trance-like experiences of God.[119] Embedded near the centre of the upper zone in the fresco, a scene shows Antony receiving Christ’s blessing (Fig. 14). Although the next stage of the journey was not represented in the Thebaid, the viewer might have understood that the gate into a perfect garden would be open.

I wish to acknowledge the insightful and generous assistance of the reviewers, the editors and John Renner. Funding for the research came from the Canadian federal government (SSHRC).

References

| ↑1 | On an appropriate title for the fresco: Amelia Hope-Jones, “Images of the Desert, Religious Renewal and the Eremitic Life in Late-Medieval Italy: A Thirteenth-Century Tabernacle in the National Gallery of Scotland”, 2 vols (Ph.D. Thesis, University of Edinburgh, 2019), v. 1, pp. 23-26. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Judith Adler, “Cultivating Wilderness: Environmentalism and Legacies of Early Christian Asceticism”, Comparative Studies in Society and History, 48/1 (2006), 4-37, at 5-9. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0010417506000028. |

| ↑3 | For example, Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Nature”, in Emerson: Essays and Poems (New York, Penguin, 1996), pp. 106, 111. |

| ↑4 | Adrien Rouquette, La Thébaïde en Amérique, ou Apologie de la vie solitaire et contemplative (New Orleans: Meridier, 1852), p. 91. |

| ↑5 | Lawrence Buell, “Ecocriticism: Some Emerging Trends”, Source: Qui Parle, 19/22 (2011), 87-115. https://doi.org/10.5250/quiparle.19.2.0087. |

| ↑6 | Chiara Frugoni describes the “scenografica” of the landscape: Chiara Frugoni, “Altri Luoghi, Cercando il Paradiso: Il Ciclo di Buffalmacco nel Camposanto di Pisa e la Committenza Domenicana”, Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa: Classe di lettere e filosofia, 18.4 (1988), 1557-643, at 1592. |

| ↑7 | Joseph Polzer, “Aristotle, Mohammed and Nicholas V in Hell,” Art Bulletin, 46 (1964), 457-69, at 463-67. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.1964.10788789; Luciano Bellosi, Buffalmacco e il Trionfo della Morte (Turin: Einaudi, 1974). |

| ↑8 | Millard Meiss, “Notable Disturbances in the Classification of Tuscan Trecento Paintings”, Burlington Magazine, 113 (1971), 178-87, at 182 n. 15. |

| ↑9 | Antonino Caleca, “Costruzione e decorazione dalle origini al secolo xv”, in Il Camposanto di Pisa, eds C. Baracchini and E. Castelnuovo (Turin: Einaudi, 1996), pp. 13-48, at 13-30; Mauro Ronzani, “Dal ‘cimitero della chiesa maggiore di Santa Maria’ al Camposanto: aspetti giuridici e istituzionali”, in Il Camposanto di Pisa, eds C. Baracchini and E. Castelnuovo (Turin: Einaudi, 1996), pp. 49-56, at 51-55; Mauro Ronzani, Un’idea trecentesca di cimitero: la costruzione e l’uso del Camposanto nella Pisa del secolo XIV (Pisa: Edizioni Plus, 2005), pp. 33-34, 39, 40-43. |

| ↑10 | Mario Bucci and Licia Bertolini, Camposanto Monumentale di Pisa: Affreschi e Sinopie, intro. P. Sanpaolesi (Pisa: Opera della Primaziale Pisana, 1960), pp. 35-40; Joseph Polzer, unpublished book manuscript, p. 7. I am grateful to Joe, who generously, before his death, sent me his unpublished book manuscript on the early frescoes in the Camposanto. |

| ↑11 | Ronzani, Un’idea, pp. 40-41, 111-40. |

| ↑12 | Antonino Caleca, “Il Camposanto Monumentale: Affreschi e Sinopie”, in Antonino Caleca, Gaetano Nencini, Giovanna Piancastelli, and Enzo Carli, Pisa – Museo delle Sinopie del Camposanto Monumentale (Pisa: Opera della Primaziale Pisana, 1979), pp. 38-115, at 55-57. |

| ↑13 | On the sequence of the wall-paintings: Barbara K. Dodge, “Tradition, Innovation and Technique in Trecento Mural Painting: The Frescoes and Sinopie Attributed to Francesco Traini in the Camposanto in Pisa” (Ph.D. Thesis, Johns Hopkins University, 1978), pp. 24-64. |

| ↑14 | For the experience of the early frescoes in the late 14th and 15th centuries: Diane Cole Ahl, “Camposanto, Terra Santa: Picturing the Holy Land in Pisa”, Artibus et Historiae, 24 (2003), 95-122. https://doi.org/10.2307/1483733; and David Ganz, “Campo Santo, Campi Dipinti: The Legend of the Earth and the Spaces of the Camposanto’s Early Fresco Decoration”, in Journeys of the Soul: Multiple Topographies in the Camposanto of Pisa, eds M. Bacci, D. Ganz, and R. Meier (Pisa: Edizioni della Scuola Normale, 2020), pp. 65-110. |

| ↑15 | Giorgio Vasari, The Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects, ed. and intro. W. Gaunt, trans. A. B. Hinds, 4 vols (London: Dent, 1963), v. 1, pp. 144-45. |

| ↑16 | Vasari, v. 1, pp. 70-71. |

| ↑17 | Bucci and Bertolini, p. 61. |

| ↑18 | Polzer, unpublished book manuscript, pp. 179, 188. |

| ↑19 | Cathleen Hoeniger, The Fate of Early Italian Art during World War II: Protection, Rescue, Restoration, with Geoffrey Hodgetts (Turnhout: Brepols, 2024), pp. 326-39, 347-51. |

| ↑20 | Salomone Morpurgo, “Le Epigrafi Volgari in Rima del ‘Trionfo della Morte’, del ‘Giudizio Universale e Inferno’, e degli ‘Anacoreti’ nel Camposanto di Pisa”, L’arte: Rivista di storia dell’arte medievale e moderna, 2 (1899), 51-87, at 82-85; Domenico Cavalca, Vite dei Santi Padri, intro. and ed. C. Delcorno, 2 vols (Florence: Edizioni del Galluzzo, 2009), v. 1, pp. ix-xiv; Carlo Delcorno, La tradizione delle “Vite dei santi padri” (Venice: Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, 2000), pp. 515-32. As Delcorno explains, the popularity of Cavalca’s Vite is attested to by its survival, in whole or in part, in close to 200 manuscripts. |

| ↑21 | Bucci and Bertolini, p. 61. |

| ↑22 | Joseph Polzer, “The Role of the Written Word in the Early Frescoes in the Campo Santo of Pisa’, in World Art: Themes of Unity in Diversity, ed. I. Lavin, 2 vols (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1989), v. 2, pp. 361-72, at 361; Frugoni, 1589. |

| ↑23 | Some of the first publications in this vein were: Caleca, “Il Camposanto”, pp. 55-57; Frugoni, 1560-61; and Lina Bolzoni, “La Predica Dipinta: Gli Affreschi del ‘Trionfo della Morte’ e la Predicazione Domenicana”, in Il Camposanto di Pisa, eds C. Baracchini and E. Castelnuovo (Turin: Einaudi, 1996), pp. 97-114. |

| ↑24 | Several 10th-century manuscripts of the vitae patrum with a content similar to Cavalca’s collection have survived. One 12th-century manuscript, in which the sequence of the stories accords to a good degree with Cavalca and the Camposanto fresco, beginning with the vitae of Paul, Antony and Hilarion, is: Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, MS Douce 351 (English origins). |

| ↑25 | Alessandra Malquori, Il Giardino dell’Anima: Ascesi e Propaganda nelle Tebaidi Fiorentine del Quattrocento (Florence: Centro Di, 2012), pp. 21-34; Denva Gallant, Illuminating the Vitae Patrum: The Lives of Desert Saints in Fourteenth-Century Italy (University Park: Penn State University Press, 2024), p. 117. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780271098043. |

| ↑26 | Denva E. Jackson [Gallant], “In the Footsteps of our Fathers: Morgan Library’s Vitae Patrum, (NY, P. Morgan Library, MS. M.626)” (Ph.D. Thesis, Harvard University, 2018), p. 70. |

| ↑27 | Cavalca, pp. 467-69. |

| ↑28 | On the local Dominicans: Lina Bolzoni, The Web of Images: Vernacular Preaching from Its Origins to St. Bernardino da Siena, trans. C. Preston and L. Chien (Burlington, Vt.: Ashgate, 2004), pp. 20-22. |

| ↑29 | Frugoni, 1593-94, 1613-17; also Malquori, p. 90. |

| ↑30 | Hope-Jones, v. 1, p. 199. |

| ↑31 | Cavalca, pp. 524-40, 562-66, 635-36. |

| ↑32 | The conversation was recorded in the Apophthegmata Patrum (or Sayings of the Fathers), as Cavalca knew; Cavalca, Vite patrum, Biblioteca Laurenziana, Florence, MS San Marco 386, fol. 98r. |