Alexandra Dodson • Notre Dame of Maryland University

Recommended citation: Alexandra Dodson, “From Mount Carmel to the Comune: The Eremitical Life in Carmelite Legislation,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 12 (2025). https://doi.org/10.61302/MHVS9526.

The Carmelite order was born of the desert.[1] The central panel of the predella of Pietro Lorenzetti’s 1329 Pala del Carmine richly illustrates the order’s eremitical origins in the arid landscape of Mount Carmel (Fig. 1). The panel depicts Albert, Patriarch of Jerusalem, presenting the order with its first rule, sometime between 1206-1214. The Carmelites kneel before him, clad in the striped habits they wore until 1287, with a fountain and a small church behind them. The craggy background takes the form of a Thebaid scene as the hermits of Mount Carmel go about their lives in the manner of the desert fathers. Some sit in solitude in caves, others walk the hills, surrounded by lions. The rural, eremitical life is depicted as an integral part of the order’s beginnings.

Fig. 1. Pietro Lorenzetti, The Carmelites Receiving the Rule from Albert of Vercelli, detail of the predella of the Pala del Carmine. Siena, Pinacoteca Nazionale. Image © Museum of Modern Art licensed by SCALA/Art Resource NY.

Fig. 2. San Niccolò del Carmine, Siena. Photo: author.

Yet the altarpiece was created for the high altar of the urban, mendicant church of San Niccolò del Carmine in Siena, where the Carmelites had been established at least since 1256 (Fig. 2). The Carmelites had remained in their hermitage on Mount Carmel until the late 1230s, when they began to migrate westward, first to Cyprus, then to Sicily, France, England, the Italian peninsula, and elsewhere, where they began to operate as mendicant friars.[2] The order maintained the hermitage until the fall of Acre in 1291, after which they no longer had a presence in the Holy Land. Thus, by the time Lorenzetti completed the altarpiece in 1329, the Carmelites had been in western Europe for nearly a century, and mendicant friars for almost as long.

Fig. 3. Pietro Lorenzetti, Pala del Carmine, partial reconstruction. Siena, Pinacoteca Nazionale. Image © Foto Lensini Siena.

Mount Carmel looms large in the remainder of the altarpiece, a public statement about the history and traditions of the order (Fig. 3). Most notably, the central figure of the Virgin Mary is flanked to her left by the Prophet Elijah, whom the Carmelites claimed as their founder. Elijah is depicted as a Carmelite, wearing the white and black habit that the order adopted in 1287, as is his disciple Elisha, on the left side of the polyptych (Fig. 4).[3] By linking themselves to Elijah, who had lived on Mount Carmel and been upheld for centuries as a model of religious life, the Carmelites were creating a narrative of a storied and prestigious past.[4] The latter years of the 13th and early years of the 14th centuries were a time of reckoning for the order. The Carmelites had narrowly survived the fraternal purge of the Second Council of Lyon in 1272, but were now competing for space and patrons with other, more established orders, who had been in the west decades before the Carmelites, and had canonized founders to boot.[5] Connections to the Old Testament and the Holy Land could set the Carmelites apart.

Fig. 4. Pietro Lorenzetti, The Prophet Elisha, detail of the Pala del Carmine. Image: The Norton Simon Foundation.

Lorenzetti doubtlessly received detailed instructions for the depiction of Mount Carmel from the Carmelites, demonstrating that, though urban locations and pastoral responsibilities created new realities for the friars, their origins in desert cells figured strongly in their imaginations.[6] But to what extent did the order’s eremitical past influence its day-to-day operations? Would the Sienese Carmelites have seen themselves in the hermits of Lorenzetti’s Thebaid? And to what extent did they intend their urban convent to emulate their first hermitage?

Carmelite architecture has received less attention that that of the other mendicant orders, namely the Franciscans and Dominicans. While some individual churches and their decoration have been amply studied, there has been no systematic study of the order’s approach to building and conventual living in its earliest years.[7] Through an analysis of extant Carmelite texts and legislation, primarily rules and constitutions written between the early 1200s and mid-1300s, I seek to determine how the Carmelites might have intended to maintain their eremitical structure, and how they succeeded in their mendicant reality. The texts provide glimpses of the order’s aims for the built environments in which they would eat, sleep, pray, and minister. In rare cases, the texts are supplemented by architectural evidence; the convents themselves have been the subject of substantial modification over the centuries and analysis of their 13th-century configurations is challenging and tenuous at best. My reading of these texts allows us to glean important insight into the order’s official identity and the way in which it was caught between the eremitic ideal and the mendicant practicality.

While the order maintained the Mt. Carmel hermitage until the end of the 13th century, it did not serve as an administrative “mother house” for the order in the manner of San Francesco in Assisi for the Franciscans or San Nicolò in Bologna (now San Domenico) for the Dominicans, which contributed to a decentralized structure of record-keeping and the loss of much information outside of the texts considered here. Though these texts pertain to the entirety of the order, my study focuses primarily on the Tuscan province, where surviving documentary, artistic, and architectural evidence is greater than elsewhere, though still incomplete.[8] The region also contains rich mendicant and monastic sites, including major houses for the Franciscans, Dominicans, Vallombrosans, and Camoldolese, and is home to the origins of the unified Augustinian order. Critically, it is in Tuscany where the strongest examples of the Carmelites’ call to the desert are found. The province was home not only to Lorenzetti’s altarpiece, but also to the earliest Carmelite reform movement, in which some friars sought a return to the eremitic life.

The Formula Vitae of Albert of Vercelli

The Carmelites received their first formula vitae from Albert, Patriarch of Jerusalem, sometime between 1206-1214.[9] It is likely that most members of the community were lay brothers, not ordained to celebrate mass or perform other pastoral duties.[10] The brief rule primarily outlines the proper comportment, employment, and daily schedule of the brothers. They were to renounce personal property, fast, engage in manual work, read the psalms, and gather daily for mass. The few strictures related to the physical space of the hermits’ base are concerned with the brothers’ cells.

First, the rule states that each brother was to have a separate cell, allotted by the Prior, whose cell was to be situated near the entrance to the property so that he would be the first to meet visitors. The rule further states that the brothers were not to exchange cells with each other, or to be in a cell other than their own, without the permission of the Prior. They were to stay in or close to their cells in contemplation and prayer, unless attending to another duty.[11] The primitive rule made only one requirement for a communal space: “An oratory, as commodious as possible, built in the middle of the cells.”[12] The brothers were to gather daily in this oratory for mass, if it could be done without difficulty. The use of the word “commodious” stands in sharp contrast to the architectural legislation that would be developed in the coming decades by other religious orders, and to those that already existed for orders like the Cistercians. The Carmelites were bound by Albert’s formula vitae to poverty, yet, unlike the earliest Franciscans, they were attached to a fixed settlement, the hallmark of which was the insistence upon individual cells for spiritual contemplation.[13]

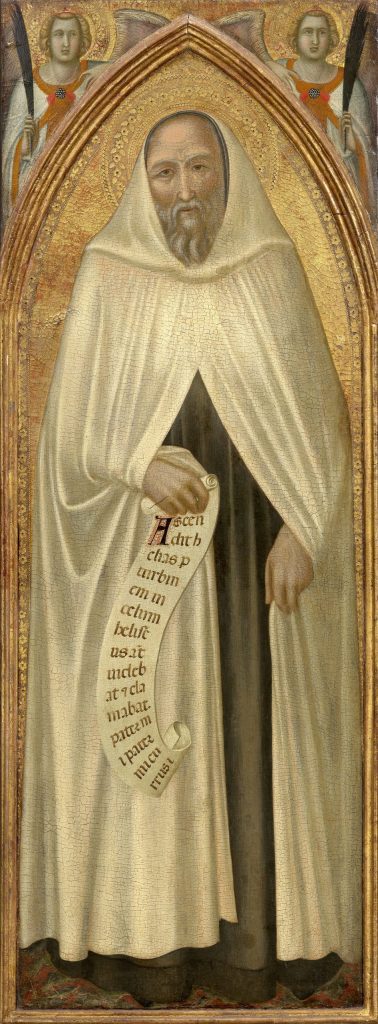

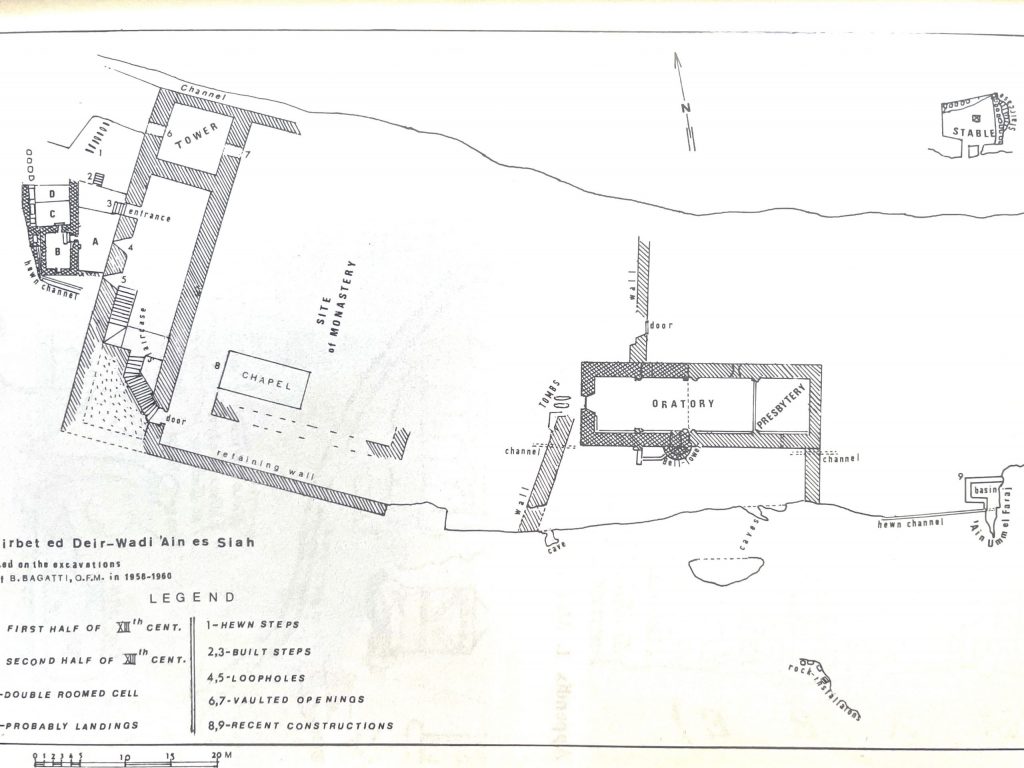

Fig. 5: The Early Carmelite Hermitage on Mount Carmel. From Elias Friedman, The Latin Hermits of Mount Carmel: A Study in Carmelite Origins (Rome: Teresianum, 1979), Map 5.

The precise configuration of the Carmelites’ first settlement on Mount Carmel is not known, though the community was mentioned by crusaders and travelers, including Jacques de Vitry, who described the site: “After the example of that holy man and solitary the prophet Elijah, (they) led the hermit life on Mount Carmel…near the spring called Elijah’s Spring…in little cells like so many hives where, as bees of the Lord, they produced the honey of spiritual sweetness.”[14] Archaeological excavations have provided some evidence for the structure of the early settlement. Three separate components of the early complex have been discovered – the oratory, a cell, and a staircase, which are aligned with the provisos set forth in Albert’s rule (Fig. 5).[15] The cell, positioned at the entrance to the hermitage, has been identified as that of the prior. The cell consisted of two rooms, one of which contained a small niche in which an object, such as an image of the Virgin, might be placed.[16] Additional cells for individual hermits were demolished for construction of a monastery later in the 13th century, which has not been excavated.[17]

The 1247 Mitigation of the Carmelite Rule

When the Carmelites began to leave Mount Carmel in the 1230s, it appears they intended to remain hermits. Their earliest western foundations in Cyprus, Sicily, Provence, and England were relatively rural, not conducive to active ministry.[18] Gregory IX’s 1229 Religionis vestra had placed the Carmelites in a state of mendicant-type poverty, prohibiting the brothers from any possession of property and offering them papal protection.[19] Without the ability to own land the Carmelites could not develop along the lines of a traditional monastic order, earning income from tenants and agricultural production. As a result, they were dependent on donations, which, in their isolated settlements, far away from most potential patrons, were few.[20] As a matter of survival, the Carmelites must have observed the Franciscan and Dominican orders as a functional “business model” to emulate. Those orders, deeply engaged in urban ministry, were immensely popular with the laity. Their friars were constructing spacious churches and piazzas to accommodate those who wished not only to hear their preaching, but also to be buried within their complexes.[21]

At the Carmelites’ general chapter meeting in 1247, it was decided to petition Innocent IV to allow a modification of the rule.[22] Innocent IV assigned two Dominican friars to assist them, Cardinal Hugh of St. Cher and William of Reading, Bishop of Tortosa, and confirmed the modifications in the bull Quae honorem conditoris omnium of October 1, 1247. The changes were minimal. Prescriptions for separate cells for the brothers, as well as the location of the prior’s cell remained the same. Only two additions referring to the location and design of the settlements were made. The first stated that, “If the prior and brothers see fit, you may have foundations in solitary places, or where you are given a site that is suitable and convenient for the observance proper to your Order.”[23] This statement was key in the Carmelites’ transformation from hermits to mendicants as it presented the brothers with options for their settlements, allowing them to locate where they “see fit.” They could continue to establish themselves in isolated locations, as on Mount Carmel, or they could take advantage of other sites that they might be granted – even if they were urban.[24]

The second addition referred to the design of the settlements themselves, noting that the brothers were to eat together in a common refectory while listening to a reading from the Holy Scripture. Even so, the directive remained that the brothers were to stay in their own cells or nearby, spending their time in prayer “unless attending to some other duty” – it seems that communal repast was now one of the “other duties” that might engage a brother.[25]

These duties expanded as the Carmelites were granted more pastoral privileges and responsibilities. Prior to confirming the adapted rule, Innocent IV had issued Quoniam ut ait in 1245, asking Christians to assist the Carmelites, and Cum dilecti filii, asking for assistance in finding the Carmelites places to live.[26] In 1252, with Ex parte dilectorum, Innocent asked bishops to protect the Carmelites, permitting them to build cells and churches, and to have cemeteries and bells. The text of this bull, it should be noted, uses the term cella, rather than conventus, which would have been more in line with construction of a full mendicant complex.[27] The following year, they were given permission to preach and hear confession, and in 1261, they were permitted to allow the laity to frequent their churches.[28]

Cells and Dormitories

The insistence on individual cells in the early Carmelite rules stands at odds with the order’s increasingly mendicant existence as the 13th century progressed. As they turned away from the central oratory surrounded by cells, the Carmelites needed new architectural models. The Franciscans and Dominicans seem the obvious choice, but there were a variety of approaches to communal living taken by other orders, cenobitic and eremitic. Chapter 22 of the Rule of St. Benedict specified in regard to sleeping arrangements that “…if possible, all are to sleep in one place.”[29] Dormitories in Cistercian monasteries were thus generally constructed as large open spaces, yet there is evidence that monks were partitioning this space in an effort to create a modicum of privacy.[30] To Cistercian leaders, though, privacy was dangerous. In an open dormitory, such as the one at Santes Creus in Catalonia, little could be hidden (Fig. 6). Smaller, less public spaces, however, could host and hide consumption of indulgent meals, as well as conspiracies, as outlined by the 1370 Cistercian general chapter, which called for the destruction of cells in dormitories.[31] The Cistercians, though, were not an order focused on solitude and individualism. The Carthusians, who were committed to solitude, might have been of interest to the Carmelites.[32] The Carthusian charter saw the monastery as a desert and made correlations between cells and tombs, in line with their practice of being “dead to the world” using prayer, work, and mortification in the cell to remove external connections and distractions from the self.[33] An early customary on solitude lauds, among others, Moses, Elijah, Elisha, and John the Baptist.[34] Such emphasis on solitude and cellular living draws a comparison to the early Carmelites, and indeed, Albert of Vercelli would almost certainly have been familiar with the Carthusians.[34]

Fig. 6. Open dormitory at the Cistercian monastery of Santes Creus in Catalunya, late 12th to early 13th century. Photo: Erik Gustafson.

Also of consideration should be the Camaldolese, who were to live individually in cells in proximity to a monastery, under the authority of an abbot.[35] The hermits could choose to remain in constant seclusion, or they could emerge for communal meals and manual labor.[36] While most Camoldolese monasteries were in rural settings, there were a number in cities by the end of the 13th century, including Santa Maria degli Angeli in Florence.[37] There we have examples of how the order tackled the problem of establishing their eremitic lifestyle in an urban setting. They practiced severe claustrum, building high walls around their complex. They slept in dormitories partitioned into cells, maintaining their seclusion.[38] The Vallombrosans operated similar urban settlements.[39] The structure of this order was both cenobitic and eremitic – the brothers were strictly cloistered, but the community included many conversi who interacted with the outside world.[40]

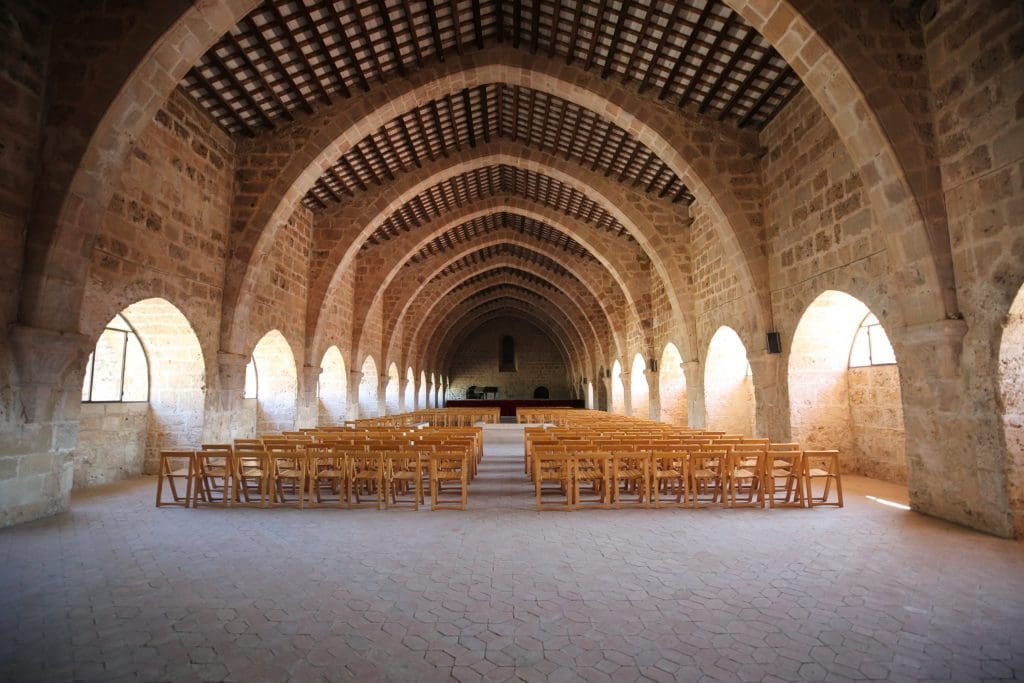

Dominican and Franciscan documents and legislation address the architecture of both their churches and conventual dwellings. St. Francis was notably drawn to the eremitical life. The order’s early duality can be seen in Jacques de Vitry’s 1216 description of their daily activities: “During the day they go into the cities and villages giving themselves over to the active life in order to gain others; at night, however, they return to their hermitage or solitary places to devote themselves to contemplation.”[41] The Franciscans’ early settlement at the Porziuncola in Assisi might have contained individual cells with a church at the center – not dissimilar to the Camaldolese, or the arrangement at Mount Carmel.[42] The Franciscan rules of 1221 and 1223 make no specific provisions for the living arrangements of the brothers, aside from insistence on poverty, nor does Francis’s testament.[43] The 1260 Constitutions of Narbonne include limited mention of the sleeping arrangements of friars, devoting more attention to the observation of poverty within church architecture. They do state that “No brother, with the exception of the ministers and the lectors in the general study houses, may have a private room separate from the dormitory.”[44] The use of a hall-style dormitory at Greccio, however, suggests that there was variation in practice (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Hall-style dormitory at the Franciscan convent at Greccio, built in the mid to late 13th century. Photo: Erik Gustafson.

The situation for the Dominicans differed by virtue of the nature of the order, clerical from the outset. As early as 1216, Dominic and his brothers began to build a cloister and cells for study and sleeping at the church of St. Romain in Toulouse.[45] Just a few years later, conventual structures including a dormitory, called the domus, were built at San Nicolò in Bologna. The long, rectangular dormitory, the chapter house, and the sacristy were perpendicular to the nave of the church and connected directly to the friars’ choir, a model that was often imitated in later foundations.[46] The Primitive Constitutions note that silence should be observed in the dormitory, but there is no mention of individual spaces. The 1241 redaction of the Dominican constitutions under Raymond of Penyafort, however, includes specific provisions that the walls of the dormitory building not exceed 12 feet in height, and that each friar was to have a single cell, though in certain cases (such as for the prior) a double cell could be allowed.[47] Like their churches, all Dominican buildings were to be “humble and moderate.”[48]

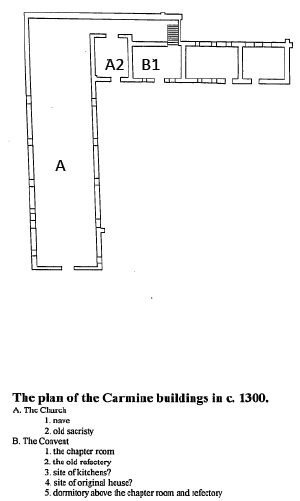

Nicholas of Narbonne and the Ignea Sagitta

While almost no precise information survives about the living arrangements of the first Carmelites in the west, a 1270 text by prior general Nicholas of Narbonne indicates that many of the brothers were eschewing the prescriptions of the rule.[49] Nicholas reveals that at least a substantial number of Carmelites in 1270 were not living in individual cells. In their new urban settings, it seems that they may have been living in communal dormitories, perhaps partitioned. Though knowledge of the 13th century is scarce, reconstructed plans of early Carmelite convents, such as Florence, reveal the dormitory to be a long, rectangular space (Fig. 8).[50]

Fig. 8. Reconstructed plan of Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence, c. 1300. Image: Patrick McMahon, “Servant of two masters: the Carmelites of Florence, 1267-1400” (PhD diss., New York University, 1993): 333.

In this document, known as the Ignea Sagitta (the “flaming arrow”) Nicholas lambasts his order for deviating from its hermetic way of life. The Ignea Sagitta is a desperate plea for the order to return to its pure, original state.[51] Nicholas casts the Carmelite order as a mother to the brethren. He casts as her legitimate sons the brothers who sought to uphold their eremitical origins, and as her stepsons those who supported urbanization and movement away from solitary contemplation.[52] He writes that the legitimate sons will welcome his letter, called the Flaming Arrow “for its bright, sharp truthfulness,” while it “will seem hateful to the stepsons, whose ill deeds it will show to be the deeds of those who hate the light.”[53] The Ignea Sagitta is comprised of fourteen chapters, several of which deal with specific repercussions of mendicancy. In the fourth, Nicholas criticizes the Carmelites for their new attempts at preaching – or “tale-telling” – a task undertaken by those afflicted with vainglory.[54] Nicholas believed that the brothers who preached had neither the education nor the experience to preach sagely: “I who have made the round of the Provinces and become acquainted with their members must sadly admit how very few there are who have knowledge enough or aptitude for these offices.”[55] Indeed, in the following chapter Nicholas criticizes pursuits of Carmelites who have abandoned solitary lives for those in the world. Those no longer living lives of desert contemplation are living in “an abyss of occasions of sin and unseemly rovings.”[56] He continues: “The main reason for your wanderings is to visit not orphans but young women, not widows in their adversity but silly girls in dalliances, beguines, nuns and highborn ladies. Once in their company you gaze into each other’s eyes and utter words fit for lovers, the downfall of right conducts and a snare to the heart.”[57] The brothers were subject to these temptations because they were away from the desert, dwelling in the wicked city and wandering outside of their cells. Solitude, he writes, was held in the highest regard by God. Abraham had ascended a mountain to sacrifice Isaac, as directed by God. Later, Lot would flee to a mountain from Sodom. Moses was alone on Mount Sinai when he received the Ten Commandments, as was Mary in her chamber at the moment of the Annunciation. Christ prayed alone on a mountain, and he spent 40 days and nights in solitude in the desert, becoming a model for the Carmelites’ predecessors.[58]

Carmelite settlement in urban locations was in direct contradiction to these examples. Nicholas takes issue with the provision of the 1247 mitigation of the rule that allowed the Carmelites to establish themselves in cities. He points out that the provision reads as: “You may make foundations in solitary places, or where land is given to you which is suitable and convenient for the observance proper to your Order.” Though cities are not suitable or convenient for proper Carmelite observance, contemporary friars, he writes, have ignored that they still might settle in solitary places.[59] In the eighth chapter Nicholas focuses on the most solitary of places – the hermit’s cell. The Carmelite rule dictated that each brother “is to have a separate cell.”[60] These cells should not be contiguous, but separate “in order that the heavenly Bridegroom and his Bride, the contemplative soul, might converse the more secretly as they repose therein.” Within the cells, the brothers were supposed to stave off idleness through engagement in spiritual tasks, namely prayer and contemplation. Without referring to specific urban convents by name, Nicholas criticizes them:

But you city dwellers, who have exchanged your separate cells for a common house, what spiritual task do you perform, there in full view of one another, what are your holy occupations? When do you ponder God’s Law and watch at your prayers? Does not all the vanity you see or hear, say or do, as you wander hither and thither all day long, come back to your memories at night?[61]

Communal living, it would seem, would lead to distractions, disagreements, and even fights between brothers.

A clue to the realities of Carmelite living situations might be found in this: “Perhaps some of you will say: ‘Although we live in the city, we have separate cells, or mean to have them by and by.’”[62] Nicholas felt that, for those living in the city, separate cells did not serve their intended purpose, as the brothers were in them only to sleep, as their days were occupied by roaming the city, and much of the night by revelry within the convent. A professed member of the order, Nicholas wrote, should rarely leave his cell.[63]

We do not know the extent to which Nicholas’ laments were based on firsthand knowledge of the origins of the order. As Andrew Jotischky noted, Nicholas was an elderly man in 1270 and thus could have joined the order on Mount Carmel prior to its first wave of migration in the 1230s.[64] A further point of interest is the closing statement of the Ignea Sagitta: “Given and executed in the year of our Lord one thousand two hundred and seventy, in the month of February, on Mount Enatrof, terrible to enemies; there is the house of God and the gate of Paradise.”[65] Though Mount “Enatrof” does not exist, Adrian Staring and Jotischky both believe it references “Fortane” (spelled backwards) which is believed to have been an early Carmelite settlement in Cyprus.[66] It is thus within the realm of possibility that Nicholas spent his early years in the order on Mount Carmel and/or Cyprus, and then retired there to write the Ignea Sagitta. Of additional note is that at the 1269 general chapter meeting at Messina, at which Nicholas may have resigned, many brothers from the Holy Land, particularly from Acre and Mount Carmel, were in attendance.[67] Their presence might have been a reminder of the early, eremitic way of life.

The haziness of Nicholas’ biography complicates the process of determining to what extent the views he articulates in the Ignea Sagitta were shared by other members of the order, and to what extent the document was circulated.[68] Even if Nicholas’ opinions were not widely shared by others, one could reasonably assume that a treatise written by the prior general would have been shared throughout the order. Yet not only are there few early copies of the Ignea Sagitta, none from the 13th century, but Nicholas himself is largely absent from the early Carmelite historical record. The first known mention of the Ignea Sagitta comes from Giovanni Grossi’s Vividarium, written between 1411-1417, of which only one 15th-century copy survives.[69] It is odd that it went unmentioned by 14th-century Carmelite authors, such as Sibert de Beka, John Baconthorpe, or Felip Ribot, leading Richard Copsey to conclude that the text was not widely circulated and had no bearing on the direction of Carmelite operations.[70] Nicholas himself seems to have been a largely unknown entity in the 14th century. He does not appear in an early register of prior generals.[71] He does, however, appear in the Florentine Carmelite necrology, entered under April 29.[72]

In some ways, Nicholas’ lament of the discrepancy between the order’s original intentions and its practical reality is similar to the protests of the Spiritual Franciscans. Indeed, even before St. Francis’ death in 1226, there were divisions in the order as friars debated the merits of retaining Francis’ vision of itinerant brothers with no property or permanent settlements. Poverty, however, was not the hill on which Nicholas (nor the Carmelites more broadly) wanted to die. In the Ignea Sagitta he mentions it only once, in the context of the monastic vows of chastity, obedience, and “renunciation of ownership.”[73] For Nicholas, it is communal living, rather than sumptuousness, that poses the greatest risk to the Carmelite tradition.[74] For all his concern about the Carmelites’ cells, in which they would engage in private devotion and contemplation, he does not mention any specifics related to the oratories used for communal worship.

The Constitutions of 1281

The Constitutions of 1281, made during the General Chapter meeting in London that year, came a decade after both the Ignea Sagitta, and the Second Council of Lyon, when the order had nearly been disbanded.[75] The order was increasingly interested in emphasizing its existence prior to the Fourth Lateran Council, evidenced by the Rubrica Prima of the 1281 Constitutions, which asserted the order’s connection to Elijah and its origins on Mount Carmel. The Rubrica also indicates that the eremitical nature of the order still remained. While the Constitutions discuss the order’s pastoral activities, such as preaching, they also proclaim that the brothers’ cells (not dormitories) adhere to the rule as much as possible. Brothers were still forbidden to leave their cells without good reason.[76] These constitutions note that silence is to be observed “in claustro, in cellis praeterquam in cella prioris, in choro, in refectorio,” revealing that (officially, if not in practice) the order still held itself to the eremitical ideals of the individual cell.[77]

The Later Constitutions

The Constitutions of 1294 were composed shortly following the order’s abandonment of Mount Carmel in 1291. Like the Constitutions of 1281, this document mandates silence in the cloister, choir, and refectory, but makes a subtle difference in language in noting that silence is to be observed “in dormitorio et in cellis, praeterquam in cella prioris.”[78] Mentioning both a dormitory and cells may be an indication of the variety of practices used by the order. The Sienese Carmelites, for example, received 1000 fiorini from the commune of Siena in 1301 for the construction of a dormitory in their convent.[79] Descriptions of the convent of Newnham, outside of Cambridge, however, reveal that the Carmelites had built both cells and a dormitory.[80] The Constitutions of 1324 give greater insight into the arrangement of cells within a common dormitory: an opening is made in each looking out into the common dormitory, so that it might be easily inspected.[81] Similar provisions existed in the 1327 constitutions.[82] Throughout the 14th century and into the 15th, changes to the constitutions and notes from the General Chapter reveal that there were often lapses in observance of the rule and behaviors that warranted censure. The General Chapter noted in 1354 that silence after Compline was rarely observed – a sign that brothers were not uniformly engaging in solitary contemplation in their cells.[83]

Also of interest are statements addressing lay access to the brothers’ cells – inciting questions about just what might have transpired in Carmelite convents at the time. In 1362 it was forbidden to eat and drink with laypersons in dormitories and bedrooms.[84] In 1419 this statement was altered to exclude only a “large company of lay persons.” Women were able to access the cloister and cells – though the door had to remain open.[85]

The Carmelites had been given permission to preach and hear confession in 1252, and to allow the laity to frequent their churches in 1261. Building relationships with the laity was inextricably tied to the cura animarum and the laity visiting the cloister (including spaces like the sacristy) were often being courted for donations, and even signing wills within the conventual complexes. For example, on May 29, 1383, Paolo di Nanni di maestro Beltrame, “pizziaolo senese del popolo di San Giovanni” signed his will in the sacristy of San Niccolò in the presence of friars Guido di Tura, Giovanni di Angelo, and Bindo di Neri da Roccastrada.[86] In 1470, Cierchi Casini, widow of Bernardini Dominici confessed to Carmelite Tommaso Lottini, and made a gift of a quantity of grain, an act that took place in Tommaso’s cell in the Siena Carmine.[87]

The Constitutions of 1294 had instructed that the door of the oratory and the choir were to be kept closed, and opened only when necessary for visitors.[88] The practice of lay access to the convent was not universally accepted. In the 15th century prior-general John Soreth set about a reform of the order, which he believed to have lapsed following the second mitigation of the rule in 1432. He complained about the accessibility of the cloister, saying: “But what is to be said of cloisters in name only, open to persons of both sexes…Who can observe even the bare essentials of the rule in such public and noisy dwellings?”[89] He also emphasized the importance of the oratory being located in the center of the cells, a practice from which the order had strayed[90].

Mendicant Architectural Legislation

There is little instruction to be found in Carmelite documents pertaining to their oratory, beyond the fact that it be built in the center of the cells and, as in the rule of Albert, be “as commodious as it is able to be made,” a prescription repeated unchanged in Innocent’s 1247 mitigation of the rule.[91] Like the Franciscans and Dominicans, the Carmelites often began their tenure in new cities in pre-existing structures before building new complexes. When the Carmelites built or remodeled churches they were predominantly single-nave structures subscribing to the barn-like style favored by the mendicants for preaching and burying. Nothing about the appearance of the churches is mentioned in the 1281 Constitutions, although by the 14th century austerity was encouraged.[92] The Carmelites were certainly looking to the Dominicans (who had assisted in the mitigation of their rule) and Franciscans for architectural guidance.[93] Franciscan and Dominican legislation on the sumptuousness of their church architecture and decoration is more widely studied and cannot be addressed in detail here.[94]

The mendicants were torn between their commitment to poverty and their popularity with the laity, who flocked to their churches to hear sermons and make donations in exchange for masses and prayers. Urban IV’s 1263 bull proclaiming that the Carmelites were building a “sumptuous” monastery on Mount Carmel is thus at odds with the Dominican insistence on “mediocres domos et humiles” (in writing, if not necessarily in practice.[95] This leads to the Carmelite mendicant paradox. Though Gregory IX had prohibited the order from owning land or possessions in 1229, poverty (though practiced) had never been the defining quality of the order, as had the eremitic life. Even so, Italian Carmelite churches were smaller and simpler than many of their Franciscan and Dominican counterparts, probably because of their later foundation.[96] Though their churches were smaller, the Carmelites still divided them into spaces for the friars and for the lay public through the use of tramezzi, richly decorated walls or screens which spanned the nave, separating the friars’ choir from the area accessible to the public.[97] The tramezzi, though, were permeable, a key component of the cura animarum, rather than strict dividers, as laity could go through them to visit family chapels or meet with friars in the choir. In these spaces, the hermits of Mount Carmel were full-fledged friars.[98]

Santa Maria della Selve and the Return to the Eremitical Life

Fig. 9. Santa Maria delle Selve, Lastra a Signa. Photo: author.

However, by the mid-14th century, more than 50 years after Nicholas of Narbonne’s Ignea Sagitta, there were inklings of a movement towards the eremitical past.[99] The Provincia Toscana saw the establishment of a new Carmelite house, away from the urban bustle of daily mendicant life. (Figs. 9 and 10) Santa Maria delle Selve is located near the community of Lastra a Signa, a rural area also known as Gangalandi, about 12 kilometers west of the Florentine Carmine. “St. Mary of the Woods” was built on land donated by the di Pace family, which had property in the Borgo San Jacopo in Florence and were supporters of the Carmine.[100] The di Pace property in Gangalandi is said to have contained a house and a small oratory or chapel.[101] Legend dates the Carmelite connection to this site to the 1320s, when St. Andrea Corsini, a brother at the Florence Carmine, is said to have celebrated his first mass in this oratory, seeking refuge from the world for the monumental occasion.[102]

Fig. 10. Road to Santa Maria delle Selve, Lastra a Signa. Photo: author.

The connection between Le Selve and the Carmine was made official on March 22, 1343, when Francesco and Giovanni di Dardo di Pace donated a complex including a well, kitchen, cloister, possibly a chapter house, and a church (a building with a crypt). The Carmelites moved in immediately, and consecrated the space on April 18 the following year.[103]

Though isolated, Le Selve attracted numerous patrons, and was the frequent beneficiary of gifts in testaments throughout the 14th and 15th centuries.[104] The popularity among patrons can probably be understood in the context of the reform movements that gained widespread popularity in Florence and elsewhere in the 15th century. The church’s foundation in the 14th century may be seen as a precursor to this movement. I have mentioned the broad similarities between the Ignea Sagitta and the Spiritual Franciscans, who, under Angelo Clareno and others, advocated for strict observance of the Franciscan rule and a more hermetic lifestyle.[105] By the 1320s, when Andrea Corsini is said to have sought a rural, removed setting for the celebration of his first mass, the activities of the Spirituals, who had been condemned by the papacy, were widely known.[106]

The lure of isolation ties in nicely with the burgeoning Carmelite historiography of the 14th century, in which the order’s ties to Mount Carmel, Elijah, and the Virgin Mary were increasingly emphasized.[107] In the 1320s the Carmelites were deeply engaged in the process of building and expanding their urban churches, yet their engagement with their origins, first explicated in the Rubrica Prima of 1281, was growing. Since the fall of Acre in 1291 the order had had no physical presence in the Holy Land. As they could not actively return to their place of origin, they seem to have sought to channel their historical associations, exemplified in Pietro Lorenzetti’s predella depicteding Carmelite hermits engaged in the activities of their daily lives, glorifying the simple, contemplative nature of hermetic life. It thus seems logical that Andrea Corsini would seek a rural setting for his first mass, a setting that would allow him to connect deeply with the roots of his order, and that other Carmelite friars would be interested in following, having the opportunity to live in imitation of their predecessors.[108]

In 1399, Le Selve hosted the general chapter meeting of the order, and between 1375-1412 it was frequently used for provincial chapters.[109] Though talk of reform existed, until 1412 Le Selve functioned normally as a church of the Provincia Toscana, even though its rural setting differentiated it from the other Carmelite settlements.[110] It was first mentioned as an “observant” house in 1412.[111] In this year provincial Bartolomeo di Giovanni da Firenze named Jacopo di Alberti as prior of Le Selve, and confirmed special constitutions of the observance on the order. This did not mark a separation of Le Selve from the province or the Carmelite order; instead it simply gave Jacopo the authority to enforce a particularly spiritual and contemplative interpretation of the rule at the convent.[112] Jacopo was succeeded in 1419 by the Blessed Angelo Mazzinghi, who became known as a gifted preacher and a key figure in the observant Carmelite movement.[113]

Le Selve, the Tuscan province, and the Florence Carmine remained on good terms following the establishment of the observance in 1412. Thus within the Tuscan province there was a functional Carmelite dichotomy – the brothers at Le Selve embodied the order’s ancient eremitic lifestyle, while brothers elsewhere practiced mendicancy. Unfortunately, the surviving documentary and architectural evidence from Le Selve reveals little about the practicalities of daily life in the rural convent in the 14th and 15th centuries. Documentation of architectural modifications is extremely limited, and analysis of the convent today reveals little about its earliest form. We cannot discuss with any certainty the living quarters of the brothers – we do not know if they had truly individual cells, or whether they lived in a dormitory, subdivided or otherwise. Early works of art from Le Selve do, like works from the other Tuscan foundations, emphasize the order’s early history. The church contained an image of the Madonna, reportedly of eastern origin, a tie to Mount Carmel.[114] A 1455 tabernacle by Neri di Bicci, commissioned by Tommaso di Lorenzo Soderini, depicted Elijah and Elisha as Carmelites.[115]

Megan Holmes has suggested that the existence of Le Selve as a spiritual center for the order (replacing Mount Carmel) served as something of a justification for the urban convents and their engagement with laity.[116] A 1432 mitigation of the Carmelite rule by Eugene IV saw the relaxation of certain strictures (for example, officially permitting established practices such as brothers spending more time than permitted in the 13th-century rule time outside of their cells, and allowing the consumption of meat three times a week) for practicality’s sake.[117] As Le Selve became progressively stricter, the rest of the order became more relaxed.[118]

In 1442, Le Selve separated from the Tuscan province, becoming part of the Congregation of Mantua.[119] This observant movement was still tied to the order, but was autonomous. The goal of the reformers was to return to way of life of the ancient fathers. Lay people were not admitted to the convent, and brothers were encouraged to observe silence and remain within the convent.[120] Similar sentiments desiring a return to the primitive Carmelite rule would eventually guide the foundation of the Discalced Carmelite order later in the 16th century, under Teresa of Avila and John of the Cross. Yet even for the Carmelites not involved in the reform movements, though they had moved away from the life prescribed in Albert’s formula vitae, their eremitical origins on Mount Carmel were still at the center of their identity, reflected in the continued importance of the cell in their constitutions, if not in practice.

The Desert in the City

More work remains to better understand early Carmelite conventual life. Further archival and archaeological work are necessary, as are additional comparisons to orders not discussed in this study, such as the Augustinians, and to observant reform movements. In analyzing the discussion of architecture in early Carmelite texts, I have sought to track how the order’s approach to the built environment changed as it evolved from an eremitical to a mendicant order. Though the Carmelites did not evoke in practicality the architectural space of their first hermitage in their urban convents, the continued insistence on the importance of cells in Carmelite legislation was a reminder that the order was rooted in the solitude of the desert, seen in the idyllic hermitage on Mount Carmel depicted in Pietro Lorenzetti’s altarpiece for San Niccolò.[121] The desert and the eremitical life it fostered were critical to the order’s identity at its inception and remained so as it grew and evolved in mission.

References

| ↑1 | In fond remembrance of Kevin Alban, O. Carm. This article is derived in part from my dissertation, “Mount Carmel in the Commune: Promoting the Holy Land in Central Italy in the 13th and 14th Centuries,” Duke University, 2016. I am grateful to the editors of this journal and to the anonymous reviewers for their generous and immensely helpful feedback. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | For the history of the order’s origins, see Andrew Jotischky, The Carmelites and Antiquity: Mendicants and their Pasts in the Middle Ages (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002). The reasons for the initial migration are not fully understood, though it has historically been connected to rising tensions with Muslim neighbors. |

| ↑3 | The other full-length saints depicted on the altarpiece are St. Agnes, St. Nicholas (dedicatee of the Sienese Carmine), John the Baptist, and St. Catherine of Alexandria. The panels depicting John the Baptist and Elisha are in the collection of the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena. For detailed discussions of the altarpiece, including the full predella narrative, see Joanna Cannon, “Pietro Lorenzetti and the History of the Carmelite Order,” in Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 50 (1987): 18-28, https://doi.org/10.2307/751315. See also Christa Gardner von Teuffel, “The Carmelite Altarpiece (circa 1290-1550): The Self-Identification of an Order,” in Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz, 57 (2015): 23-35. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43611268. |

| ↑4 | For an excellent discussion of the medieval conception of the prophet Elijah, see Alison Perchuk, The Medieval Monastery of Saint Elijah: A History in Paint and Stone (Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2021). |

| ↑5 | The Second Council of Lyon sought to eliminate orders that had not existed prior to the Fourth Lateran Council of 1215; the Carmelites were forced to appeal to the council and undergo institutional changes, including increased clericalization and increased attendance at the universities. For this, see Frances Andrews, The Other Friars: the Carmelite, Augustinian, Sack and Pied Friars in the Middle Ages (Woodbridge: The Boyden Press, 2006). |

| ↑6 | Lorenzetti’s altarpiece was a stunning departure from earlier Carmelite art, which had primarily consisted of images of the Virgin Mary, many of which were said to have been brought from the Holy Land. |

| ↑7 | Emanuele Boaga, O. Carm., began to organize churches and convents based on their spatial configuration, but did not give detailed architectural or documentary evidence. See Emanuele Boaga, “L’Architettura dei Carmelitani,” in Fons et culmen vitae Carmelitane: Proceedings of the Carmelite Liturgical Seminar at S. Felice del Benaco, 13-15 June, 2006, ed. by Kevin Alban (Rome: Edizioni Carmelitane, 2007). |

| ↑8 | The Carmelites were present in Tuscany at least from 1249, when they are documented in Pisa. The date of the official establishment of the Provincia Toscana is not known, but Andrea Sabatini places it prior to 1267. See Sabatini, “Origini e antichità della provincia Toscana dei Carmelitani,” in Analecta Ordinis Carmelitarum 14, 1949, 186-188. In 1333, the convents of the province were Pisa, Siena, Florence, Lucca, Perugia, Pistoia, Prato, Montecatini, Arezzo, Perugia, Rome, Viterbo, and Civitavecchia. Siena, Rome, Viterbo, Civitavecchia, Arezzo, and Perugia would then leave to form the Provincia Romano. See Sabatini 199. |

| ↑9 | Albert had become patriarch in 1204, elected by the canons of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. A member of the Avogadro family, he was born in Castle Gualteri in Reggio Emilia, was named bishop of Vercelli, and also wrote the rule for the Humiliati. He was murdered in 1214 during a procession in Acre. See Joachim Smet, The History of the brothers of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, ca. 1200 AD until the Council of Trent (Private Printing: 1975): 7-8. The original text of the formula vita does not survive; it has been reconstructed from later copies. See Jotischky, The Carmelites and Antiquity, 10. A text purported to be the original rule is provided in Felip Ribot’s 14th-century De institutione primorum monachorum. For this text, see Felip Ribot, The Ten Books on the Way of Life and Deeds of the Carmelites, ed. Richard Copsey (Faversham and Rome: St. Albert’s Press and Edizioni Carmelitane, 2005). Oddly, Ribot’s compendium of texts (generally believed to have been much of his own creation) contain an earlier rule, said to have been given to the Carmelites in the Byzantine period during the reign of the emperor Arcadius. This rule was given by John, bishop of Jerusalem, to his disciple Caprasius. The rule was presented as a quote from Cyril of Constantinople, and was said to be documenting the way of life the Carmelites had followed since the time of Elijah and Elisha. See Andrew Jotischky, The Perfection of Solitude: Hermits and Monks in the Crusader States (Pennsylvania State University Press, 1995): 117. |

| ↑10 | Smet, The Carmelites, 34. |

| ↑11 | For the rule, see The Rule of St. Albert: Latin Text Edited with an Introduction and English Translation, ed. and trans. Bede Edwards (Aylesford: Carmelite Book Service, 1973), and “Regula Ordinis Fratrum Beatissime Virginis Marie de Monte Carmelo,” in Corpus Constitutionem Carmelitarum (Rome: Edizioni Carmelitana, 2011): 46. Carlo Cicconnetti found roots for the insistence on not changing cells without permission both in the Regula canonicorum of Pietro de Honestis and in the rule of Grandmont. Carlo Cicconnetti, La Regola del Carmelo: Origine, Natura, Significato (Rome: Institutum Carmelitanum, 1973): 393. |

| ↑12 | The original text states “Oratorium, prout comodius fieri poterit, construatur in medio cellularum.” See “Regula Ordinis Fratrum Beatissime Virginis,” 46. |

| ↑13 | The Franciscan order was approved by Innocent III in 1210. It is not certain if the first Carmelites could have been familiar with Francis, as the exact date of Albert’s issuance of their rule is not known. |

| ↑14 | Translation from Edwards, The Rule of St. Albert, p. 11. The original text reads “Alii ad exemplum sancti viri et solitarii Elyae prophetae in monte Carmelo…iuxta Fontem, qui Fons Elyae dicitur…vitam solitarium agebant in alvearibus modicarum cellularum, tamquam apes Domini dulcedinem spiritualem mellificantes.” See Jacques de Vitry, Historia orientalis, cc. 51-52, ed. J. Bongars, Gesta Dei per Francos I (Hannover: 1611): 1074 ss. Cf. Cicconetti, La Regola, 238. The “fountain of Elijah” appears in Lorenzetti’s predella, both in the central panel in which Albert presents the rule, and in a small panel to the left in which two Carmelites are depicted at work and study. |

| ↑15 | Bellarmino Bagatti, “Relatio de excavationibus,” in Analecta Ordinis Carmelitarum Discalceatorum (3, 6, 7), 1958, 1961, 1962. |

| ↑16 | Elias Friedman, The Latin Hermits of Mount Carmel: a study in Carmelite Origins (Rome: Teresianum, 1979): 159-160. |

| ↑17 | Elias Friedman, The Latin Hermits of Mount Carmel: a study in Carmelite Origins (Rome: Teresianum, 1979): 159-160. |

| ↑18 | For the earliest English settlements, see Keith Egan, O.Carm, “An Essay Toward a Historiography of the Origin of the Carmelite Province in England, in Carmelus 19 (1972): 67-100. The first four establishments were Hulne, Aylesford, Losenham, and Bradmer. The first brothers at Aylesford, led by patron Richard de Grey, also likely came directly from the Holy Land. See Frances Andrews, The Other Friars, 23-24. |

| ↑19 | See Andrews, The Other Friars, 13. |

| ↑20 | Egan, “Historiography,” 90. |

| ↑21 | For the friars’ economic strategies, see Caroline Bruzelius, Preaching, Building, and Burying: Friars in the Medieval City (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2014). |

| ↑22 | Paul Robinson, O. Carm, The Carmelite Constitutions of 1358: a critical edition with introduction and notes (Rome: Pontificia Studiorum Universitas A S Thoma Aq. in Urbe, 1992): 12. |

| ↑23 | The key point of the modification reads “Loca autem habere poteritis in heremis, vel ubi vobis donate fuerint,” see Cicconetti, La Regola del Carmelo, 231-43. |

| ↑24 | Cicconetti, La Regola del Carmelo, 231-43; see also Jotischky, The Carmelites and Antiquity, 15. |

| ↑25 | Cicconetti, La Regola, 234-235. |

| ↑26 | See Adrian Staring, “Four Bulls of Innocent IV: A Critical Edition,” in Carmelus 27 (1980), and Andrews, The Other Friars, 14. |

| ↑27 | Robinson, Constitutions of 1358, 98. |

| ↑28 | Andrews, The Other Friars, 17. The hermitage on Mount Carmel offers evidence of later additions that reflect the revised rule. Urban IV’s bull of 19 February 1263, Quoniam ut ait Apostolus, mentioned the brothers on Mount Carmel constructing a “monastery” of “sumptuous proportions” and offered an indulgence to those who contributed to its completion. The Mount Carmel oratory, dedicated to the Blessed Virgin, was enlarged in the second half of the 13th century. The pre-1247, western part of the oratory is described as made of rough, uncut stone, with the exception of the apertures, which were framed by cut stones. The later addition to the east, however, was more elaborate, notably, the roof was likely vaulted. See Friedman, The Latin Hermits, 165. |

| ↑29 | The Rule of St. Benedict, Chapter 22. Quoted from The Rule of St. Benedict in English, ed., Timothy Fry, O.S.B., (New York: Vintage Books, 1998): 30. |

| ↑30 | At Jervaulx Abbey in Yorkshire, socket holes likely from the early years of the 13th century have been identified in the dormitory as evidence of efforts to erect partitions. See Virginia Jansen, “Architecture and Community in Medieval Monastic Dormitories,” in Studies in Cistercian Art and Architecture, vol. 5, ed. Meredith Parsons Lillich (Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 1998): 74-75. |

| ↑31 | David Bell, “Chambers, Cells, and Cubicles: the Cistercian General Chapter and the Development of the Private Room,” in Perspectives for an Architecture of Solitude: Essays on Cistercians, Art and Architecture in Honor of Peter Fergusson, ed. by Terryl N. Kinder (Citeaux: Brepols, 2004): 190. Throughout the 14th century efforts had been made to curtail individualization of space in Cistercian dormitories, most notably in 1335 when Benedict XII issued the bull known as the Fulgens sicut stella calling for Cistercian reform. Intending to revert monastic life to its original practice, Benedict banned the construction of individual cells and ordered that existing cells be demolished within three months. See Bell, “Chambers, Cells, and Cubicles,” 189-190. Exceptions to the ban on individual cells were made only for the infirm, or those who might be excused “by virtue of their office.” |

| ↑32 | Though founded in the 11th century, the Carthusian order’s first foundation in Tuscany was made at Maggiano, near Siena, when Cardinal Riccardo Petroni made a bequest in his will in 1314. See Brendan Cassidy, “The Tombs of the Accaioli in the Certosa del Galluzzo outside Florence,” in Studies in Carthusian Monasticism in the Late Middle Ages, ed. Julian M. Luxford (Turnhout: Brepols, 2008): 329. |

| ↑33 | Julian M. Luxford, “The Space of the Tomb in Carthusian Consciousness,” in Ritual and Space in the Middle Ages: proceedings of the 2009 Harlaxton Symposium, ed. Frances Andrews (Donington: Shaun Tyas, 2011): 274-275, 278. |

| ↑34 | An anonymous 13th-century text compares the two orders: “Ratione contemplationis… Carthusienses …cellis includuntur, et eadem de causa Fratres Ordinis Carmeli habent cellas separatas pro contemplatione habenda. Oliger, Regula reclusorum in Ant. 9 (1934). Cf Cicconnetti, 255 n. 6. |

| ↑35 | The most comprehensive study of the Camaldolesi in Italy is Cecile Caby, L’eremitisme rural au monachisme urbain: Les Camaldules in Italie a la fin du Moyen Age (Rome: Ecole Francaise du Rome, 1999), though she does not provide deep analysis of surviving architectural structures. See also Erik Gustafson, Tradition and Renewal in the Thirteenth-Century Franciscan Architecture of Tuscany” (Ph.D. diss., New York University, 2012): 214, and “Camaldolese and Vallombrosan: Architecture and Identity in Two Italian Reform Orders,” in Other Monasticisms: Studies in the History and Architecture of Religious Communities Outside the Canon, 11th-15th Centuries, ed. Sheila Bonde and Clark Maines (Turnhout: Brepols, 2022): 161-208. |

| ↑36 | Caby, L’eremitisme, 72-73. |

| ↑37 | Gustafson, “Tradition and Renewal,” 180. Gustafson catalogued the typologies of the surviving Camaldolese churches in Tuscany, finding that most were single-naved, some with transepts. |

| ↑38 | Caby, L’eremitisme, 193. |

| ↑39 | Gustafson, “Tradition and Renewal,” 154-155. See also Kaspar Elm, “La congregazione di Vallombrosa nella sviluppo della vita religiosa altomedievale,” in I Vallombrosani nella società italiano dei secoli XI e XII, ed. Giordano Monzio Compagnoli (Vallombrosa, 1995), and Italo Moretti, “Architettura degli Insediamenti Eremitici in Toscana,” in Ermites de France et d’Italie (XIXV Siecle), ed. André Vauchez (Rome: École Française de Rome, 2003). |

| ↑40 | Gustafson, “Tradition and Renewal,” 155. |

| ↑41 | See William Short, “Recovering Lost Traditions in Spirituality: Franciscans, Camaldolese and the Hermitage,” in Spiritus: A Journal of Christian Spirituality 3 (2003): 211, and “Jacques de Vitry, Letter I” in Francis of Assisi: Early Documents I, ed. Regis J. Armstrong, J.A. Wayne Hellman, and William J. Short, (New York: New City Press, 1999-2001): 579. |

| ↑42 | Short, “Franciscans, Camaldolese,” 214. |

| ↑43 | However, a short text survives from Francis, written between 1217-1222, providing instructions for life in hermitages. The document prescribes that no more than 3 or 4 friars should go to a hermitage to practice the religious life. Within the hermitage, the friars would recite the hours and observe silence between Compline and Terce. They were not, however, to eat within their cells, in contrast to Camaldolese practice. See “A Rule for Hermitages (1217-1222),” in Francis of Assisi: Early Documents I, 61-62. A text most likely written a century later ascribes to Francis instructions for the establishment of settlements within cities that also advocated for cells. The friars were not to build large buildings – their churches were to be small, and they might have “poor little houses built, of mud and wood, and some little cells where the brothers can sometimes pray and where, for their own greater decency and also to avoid idle words, they can work.” See “A Mirror of the Perfection,” in Francis of Assisi: Early Documents III, ed. Regis J. Armstrong, J. A. Wayne Hellmann, and William J. Short, (New York: New City Press, 2001): 239. |

| ↑44 | St. Bonaventure, “The Constitutions of Narbonne,” in St. Bonaventure’s Writings Concerning the Franciscan Order, ed. Dominic Monti, OFM (St. Bonaventure: The Franciscan Institute, 1994): 92. Bonaventure’s “Instructions for Novices,” also written around 1260, include instructions for the proper position in which one should sleep – on one’s side, with legs covered, and never with one’s hands in his lap, lest he be seen “in an immodest position” – an indication of constant observance within a communal dormitory. See “Instructions for Novices,” in St. Bonaventure’s Writings, 164. Partitioning of the dormitories would, however, eventually occur. For example, at Greyfriars in London, the dormitory had been begun as an open space in 1279, but eventually divided into “dyvers lytle romes above in the Dorter.” For this, see Nick Holder, “The Medieval Friaries of London: a topographic and archaeological history, before and after the Dissolution,” (Ph.D. thesis, Royal Holloway, University of London, 2011): 94. See also Charles Lethbridge Kingsford, The Grey Friars of London; their history, with the register of their convent and an appendix of documents (Aberdeen: The University Press, 1915): 157-158. |

| ↑45 | Bruzelius, Preaching, Building, and Burying, 60, Gerard Gilles Meersseman O.P., “L’architecture dominicaine au XIII siècle,” in Archivum Fratrum Praedicatorum XVI (1946): 144, and Jordan of Saxony, Libellus de Principiis Ordinis Praedicatorum, ed. H.C. Scheeban, Vol. 16: Monumenta Ordinis Fratrum Praedicatorum Historica. Rome: 1935): 46. |

| ↑46 | See Venturino Alce, “Il convent di San Domenico in Bologna nel secolo XIII,” in Culta Bononia: Rivista di studi bolognesi 4.2 (1972) and Bruzelius, Preaching, Building, and Burying, 54-55. |

| ↑47 | William Hood, Fra Angelico at San Marco (New Haven and London: Yale University Press,1993): 196. |

| ↑48 | Richard Sundt “”Mediocres domos et humiles habeant fratres nostri:” Dominican Legislation on Architecture and Architectural Decoration in the 13th Century” in Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians (46): 401. https://doi.org/10.2307/990276. Under Humbert of Romans, master general between 1254 and 1263, Dominican legislation was enforced and convents that violated it were penalized, among them Barcelona, which had a dormitory that “notably exceeded the height designated by the Order.” |

| ↑49 | Jotischky, The Carmelites and Antiquity, 80. It is likely that Nicholas succeeded Simon Stock as prior general. Nicholas is referenced as prior general of the Carmelite order in a letter of Alphonse, Count of Poitiers, younger brother of Louis IX, who died in 1271. See Correspondance administrative d’Alphonse de Poiters, Vol. ii (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1900): 504, no. 1961. |

| ↑50 | In Florence, for example, construction on the Carmine would not have been far along at the time of Nicholas’ writing, however the first conventual structure was a single wing with a chapter house and refectory on the lower level and a dormitory, divided into cells on the upper. See Patrick McMahon, O. Carm., “Servant of two masters: the Carmelites of Florence, 1267-1400” (PhD diss., New York University, 1993): 98-99. Prisca Giovannini and Sergio Vitolo, Il Convento del Carmine di Firenze: caratteri e documenti (Florence: Tipografia Nazionale, 1981): 77. McMahon proposes the possibility that some of the first Carmelites in Florence were also living in a house on the site of the land donated to them, as he reasonably considers it unlikely that the 30 friars living in the convent by 1300 could all be in the dormitory. |

| ↑51 | The Latin text of the Ignea Sagitta is found in “Nicolai Prioris Generalis Ordinis Carmelitarum Ignea Sagitta,” ed. Adrian Staring, in Carmelus 9 (1962). This edition was translated by Bede Edwards, OCD as The Flaming Arrow by Nicholas, Prior General of the Carmelite Order (CreateSpace Independent Publishing, 2014). |

| ↑52 | Ignea Sagitta, 22. |

| ↑53 | Ignea Sagitta, 23. The motif of the flaming arrow would be repeated in later Carmelite doctrine and hagiography, particularly that of St. John of the Cross and St. Teresa of Avila. |

| ↑54 | Ignea Sagitta, 31. |

| ↑55 | Ignea Sagitta, 32. |

| ↑56 | Ignea Sagitta, 33. |

| ↑57 | Ignea Sagitta, 33. |

| ↑58 | Ignea Sagitta, 36-37. Oddly, Nicholas makes no mention of Elijah, who, while not mentioned in Carmelite texts until the following decade, would have been a common medieval example of solitary spirituality. |

| ↑59 | Ignea Sagitta, 39. |

| ↑60 | Ignea Sagitta, 42. |

| ↑61 | Ignea Sagitta, 42. |

| ↑62 | Ignea Sagitta, 43. |

| ↑63 | Ignea Sagitta, 43-44. |

| ↑64 | Jotischky, The Carmelites and Antiquity, 81. |

| ↑65 | Ignea Sagitta, 57. |

| ↑66 | Richard Copsey, “The Ignea Sagitta and its Readership: a Reevaluation,” in Carmelus 46 (1999): 172, and Jotischky, The Carmelites and Antiquity, 81. See “The List, Domus in Terra Sancta,” in Adrian Staring, Medieval Carmelite Heritage, 262-266 – “Fortanie” was listed in a 14th-century document as the first Carmelite settlement on Cyprus. Jotischky also notes the problematic contradiction that Nicosia and Famagusta have been noted by other scholars as the first Cypriot houses, and that Fortanie may not have existed in this period. The Carmelites and Antiquity, 81. |

| ↑67 | Copsey, “The Ignea Sagitta,” 172. |

| ↑68 | Nilo Geagea believed that Nicholas’ text was indicative of a major divide within the order. Nilo Geagea, O.C.D., Maria Madre e Decoro del Carmelo (Rome: Teresianum, 1988): 125. Richard Copsey, however, rejected that possibility, noting that, in 1270, the Carmelites were not actively pursuing new hermetic foundations; they were instead focusing on new urban locations. Copsey, “The Ignea Sagitta,” 164-165. |

| ↑69 | Copsey, “The Ignea Sagitta,” 166. The surviving copy is in the British Library, MS Cotton Vitellius D IV 7. |

| ↑70 | Copsey allows that the 14th-century authors could have been recalcitrant to quote Nicholas as he was being critical of the order, but considered this to be unlikely. He also suggests that, if Nicholas did compose the text on Cyprus, it might have been less readily circulated than had he been in Europe at the time. “The Ignea Sagitta,” 167-172. Jotischky, however, suggests that Nicholas’ text could have been intentionally suppressed. The Carmelites and Antiquity, 81 n. 4. |

| ↑71 | The list, written by Jean Trisse, begins with Ralph Alemannus in 1271. See “The Lists of Priors General,” in Staring, Medieval Carmelite Heritage, 318. |

| ↑72 | Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze, Conventi Soppr. c. 5 786, f. 19r. It is unclear when this entry was made in the necrology. The full text of his entry (mentioning the Ignea Sagitta) is as follows: “Reverendissimus in xpo Pr ac Mgr Nicolaus Gallicus vir doctissimus atg devotissimus totius Ordinis nri psot Beatum Simonem Anglicum Prior Generalis electus in Cnv. Tholosano in festo Pentecoste 1266. Sepultus ante fuit in Aureaca, uerum armus mortis illius nondum iniermiri potuit. Hoc autem certum est quod quinq amis uixerit in Generalti, nimiri usque ad annu millesimu ducetesimum et septiagesim, quo lempore vesignabit officiu, et discessit in eremum, ubi insignem quondam librum coscripsit quem intitulavit Igeam sagittam, m quo flebilem ordinis nri statum multis deplorat gemitibus, quia Saracem multos Carmelitas im terra sancta occiderant.” |

| ↑73 | Ignea Sagitta, 40. |

| ↑74 | Jotischky, The Carmelites and Antiquity, 103. |

| ↑75 | For the Council of Lyon and its effect on the Carmelite order, see Richard W. Emery, “The Second Council of Lyons and the Mendicant Orders,” in The Catholic Historic Review XXXIX (1953) and Frances Andrews, The Other Friars. |

| ↑76 | Discussing the cells, the text states: “Cellule vero fratrum construantur secundum tenorum regule, in quantum possibile est.” For the text, see “Constitutiones Capituli Londinensis Anni 1281,” in Analecta Ordinis Carmelitarum XV (1950): 222 and “1281 Constitutiones,” in Corpus Constitutionum Carmelitarum, 59. |

| ↑77 | “1281 Constitutiones,” 63. As discussed above, in Florence the dormitory was divided into cells. See Patrick McMahon, “Servant of Two Masters,” 98-99. Later in the 14th century, Andrea Corsini converted the part of the old dormitory that had contained the provincial’s cell into a library for the convent, and new cells for the provincial and prior were included at the end of the new dormitory. To accomplish this, Andrea Corsini purchased a new cell for himself, a frequent practice in the 14th century. For example, the wealthy Fra Giovanni Bartolo paid six florins for a cell as described by McMahon, “Servant of two masters,” 127-129. |

| ↑78 | See Ludovico Saggi, “Constitutiones capituli Burdigalensis anni 1294,” in Analecta Ordinis Carmelitanum 18 (1953): 123-85. Saggi’s text was republished as “1294 Constitutiones,” in the Corpus Constitutionum Carmelitanum, 83-117. |

| ↑79 | Archivio di Stato di Siena, Biccherna 116, c. 35/r (gia CCLXlr), 31 gennaio 1301/02. |

| ↑80 | At Newnham: Postea se transtulerunt usque ad Newenham extra Cantebrigiam, et fecerum ibi cellulas plures, ecclesiamque claustrum et dormitorium et officinas necessarias satis honestas construxerunt, et ibidem per quadraginta annos moram fecerunt. See Liber Memorandorum Ecclesie de Bernewelle, ed. John Willis Clark (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1907): 211-212. |

| ↑81 | The constitutions state: “Item tempore dormitionis fratres in cellis suis maneant, nec usque ad pulsationem exeant, neque verbo aut nullo alio modo strepitum faciant unde dormientes possint inquietari, sub poena gravis culpae. In singulis autem cellulis communis dormitorii fiat apertura parens cancellata, per quam introspicere poterunt transeuntes, nec claudatur a quocumque, sub poena gravioris culpae per unum diem.” See “1324 Constitutiones,” Rubrica VI, in Corpus Constitutionum Carmelitarum, 125. |

| ↑82 | “1357 Constitutiones,” in Corpus Constitutionum Carmelitarum, 241. |

| ↑83 | Smet, The Carmelites, 80. |

| ↑84 | Corpus Constitutionum Carmelitarum, 319, and Smet, The Carmelites, 80. |

| ↑85 | Smet, The Carmelites, 80. Regulation of female access in religious spaces also extended to their confession, which could only be taken in open spaces. See Adrian Randolph, “Regarding Women in Sacred Space,” in Picturing Women in Renaissance and Baroque Italy, ed. by Geraldine A. Johnson and Sara F. Matthews Grieco (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997): 29-34. |

| ↑86 | Compagnia della Madonna sotto le volte dello Spedale, detta anche della Beata Vergine Maria della Buca, e anche dei Disciplinati, Dipl. Biblioteca Pubblica, 1383 mag. 29 (cas. 1088). Printed in pp. 158-159, doc. 308. Published in Le pergamene delle Confraternite nell’Archivio di Stato di Siena (1241-1785), ed. Maria Assunta Ceppari (Siena: Accademia degli Intronati, 2007). Paolo requested to be buried in the Carmine. |

| ↑87 | G.A. Pecci, Compendio di contratti sciolti esistenti presso i molto reverendi Padri di S. Maria del Carmine a Siena, compilato da me Cavaliere Giovanni Antonio Pecci. Terminato a di 25 del suddetto mese e anno, in Miscellanee, 1748, BCI. Ms. A. III. 11, n. 186, f. 70c., and Sara Recupero, “I Carmelitani a Siena: Note Storico,” Istututo Storico Diocesano: Annuario 2002-2003 (2003): 400. |

| ↑88 | “Hostium chori exterius clausum teneatur et non nisi pro necessitate et oratorium visitantium devotione aperiatur,” 1294 Constitutions, Corpus Constitutionum Carmelitarum, 85. |

| ↑89 | Cf. Smet, The Carmelites, 80. |

| ↑90 | Boaga, “L’Architettura dei Carmelitani,” notes that very few Carmelite church/convent arrangements placed the church in the middle of the dormitories, see p. 6-8. |

| ↑91 | Cicconnetti, La Regola del Carmelo. |

| ↑92 | “Que tous nos édifices soient construits avec dignité et qu’aucun ouvrage notable ne soit amorcé sous peine de couple grave.” Constitutions des Grands Carmes. Manuscrit de Lunel du XVe siècle, Cf. Panayota Volti, Les couvents des orders mendiants et leur environnement à la fin du moyen age: Le nord de la France et les ancients Pays-Bas (Paris: CNRS Editions, 2003): 18. These Constitutions also lay out an approach to building practices and a “master of works.” In all provinces the prior general was to name three brothers who would supervise construction. |

| ↑93 | See Benedict Zimmerman, OCD, Acta Capitulorum Generalium Ordinis Fratrum B.V. Mariae de Monte Carmelo Vol. 1 ab anno 1318 usque ad annum 1593, (Rome: Curiam Generalium, 1912) and Robinson, Constitutions of 1358, 93-94. Dominican historian Mandonnet also claims that the Carmelites were deeply influenced by the Dominicans. See Pierre Mandonnet, OP, Saint Dominique: l’idee, l’homme, et l’oeuvre; augmente de notes et d’etudes critiques par MH Vicare et R Ladner (Paris: Desclée de Brouwer, 1938). The Augustinian order, too, emulated Franciscan and Dominican building practices, even incorporating the Dominican constitutions into some of their own legislation. Volti, Les Couvents, 18-19. |

| ↑94 | The 1220 Dominican constitutions state: “Let our brothers have moderate and humble houses so that they should neither burden themselves with expenses, nor that others – secular or religious – should be scandalized by our sumptuous buildings.” Translation from Richard Sundt, “Dominican Legislation,” 396. The Franciscans did not codify their architectural guidelines until 1260, in the Constitutions issued from the general chapter meeting at Narbonne. However, it is unlikely that the architectural statutes issued then were new. Indeed, St. Francis’s final testament, left to his friars shortly before his death in 1226, cautioned against “…churches or poor dwellings for themselves, or anything built for them, unless they are in harmony with the poverty which we have promised in the Rule… St. Francis of Assisi, “The Testament,” St. Francis of Assisi: Writings and Early Biographies, ed. M.A. Habig (Chicago: Franciscan Press, 1983): 68, and “Constitutions of Narbonne,” 85-86. |

| ↑95 | Friedman, The Latin Hermits, 165. |

| ↑96 | In the Provincia Toscana all churches are singled-naved with the exception of San Pier Cigoli in Lucca, which has side aisles. |

| ↑97 | Marcia Hall wrote the first major studies of these screens in Italy. See “The ‘Ponte’ in Santa Maria Novella: The Problem of the Rood Screen in Italy,” in the Journal of the Warburg and the Courtauld Institutes 37 (1974): 157-173, https://doi.org/10.2307/750838, and “The Tramezzo in Santa Croce, Reconstructed,” in Art Bulletin 56 (1974): 325-41, https://doi.org/10.2307/3049260. More recent work has further developed their social and spatial implications, including Jacqueline Jung, “Beyond the Barrier: The Unifying Role of the Choir Screen in Gothic Churches,” in Art Bulletin 82 (2000): 622-657, https://doi.org/10.2307/3051415, Donal Cooper, “Access All Areas? Spatial Divides in the Mendicant Churches of Late Medieval Tuscany,” in Ritual and Space in the Middle Ages: Proceedings of the Harlaxton Symposium 2009, ed. Frances Andrews (Donington: Shaun Tyas, 2011): 90-107, and Joanne Allen, Transforming the Church Interior in Renaissance Florence (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022), who provides a thorough study of the screen in Santa Maria del Carmine. |

| ↑98 | The 1432 mitigation under Eugene IV removed the prescription that Carmelites would stay in their cells. See Ludovico Saggi, “La mitigazione del 1432 della regola carmelitane: tempo e persone,” in Carmelus 5 (1958): 3-29. |

| ↑99 | Jill Webster has also described 14th-century eremitical leanings also in Catalonia. See Webster, Carmel in Medieval Catalonia (Leiden: Brill, 1999). https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004473904. |

| ↑100 | G. Bacchi, “Santa Maria delle Selve (Lastra a Signa),” in Rosa del Carmelo (1926): 5. See also Guido Carocci, Comune di Lastra a Signa (Florence: Tipografia Minori Corrigendi, 1895): 13. Several other several prominent Florentine families from the Oltrarno, some of whom were already patrons of the Carmine or had sons in the order, also owned land in the area. Gioia Romagnoli, Selve e Lecceto: due conventi a Lastra a Signa ed un grande mercenate, Filppo Strozzi (Florence: Edizioni Polistampa, 2005): 19. Some of the Carmelites from those families were Fra Angelo Pulci, Fra Andrea Bonsi, Fra Michele e Fra Iacopo di Niccolo Gangalandi. |

| ↑101 | Bacchi mentions without precise citation a document from 1327 in which a Dardo di Pace and sons purchased land in this area. Bacchi, “Santa Maria delle Selve,” 5. |

| ↑102 | Bacchi, “Santa Maria delle Selve,” 6. See also Giuliano Salvini, Chiesa di S. Maria alle Selve nel VI Centennario della morte di S. Andrea Corsini (Signa: Tip. Tozzi, 1974): 6. Andrea was beatified by Pope Eugene IV and ultimately canonized in 1629. According to legend, his mother had prayed for a child before the Madonna del Popolo in the Florence Carmine. |

| ↑103 | The text of the donation reads as follows: “plura edificia videliceti quoddam oratorium seu domum cum vulta desubter ad modum ecclesiae et alias domos dispensam et coquinam cum curia seu claustro et puteo omnia circum circa murata cum orto seu jardino.” See Gioia Romagnoli, Selve e Lecceto: due conventi a Lastra a Signa ed un grande mercenate, Filppo Strozzi (Florence: Edizioni Polistampa, 2005): 15-18. The donation was made in the chapter house of the Florence Carmine. The document of donation survives in an 18th-century copy. See Archivio di Stato di Firenze, Corporazioni religiose sopprese 253, n. 13 c. 25s. |

| ↑104 | Romagnoli, Selve, 21. Notably, the Soderini who were long supporters of the Florence Carmine) became patrons of the choir chapel, and commissioned a tabernacle from Neri di Bicci, completed in 1455. See Eve Borsook, “Documenti Relativi alle Cappelle di Lecceto e delle Selve di Filippo Strozzi,” in Antichità Viva IX (1970): 7. |

| ↑105 | See John Moorman, A History of the Franciscan Order from its Origins to the Year 1517 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968), and David Burr, The Spiritual Franciscans: From Protest to Persecution in the Century After Francis (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2001). |

| ↑106 | As the Franciscans debated with the Spirituals, Carmelite Gerard of Bologna was one of the theologians consulted by the cardinals monitoring the debate. Auger de Spuento, a Carmelite in Provence, wrote a treatise on the issue of whether it could be asserted that Christ and his apostles had no possessions. Guy Terreni, who had been named bishop of Majorca in 1321, transferred to Elne in 1332, and represented Sancho of Majorca and James II of Aragon at the papal court, wrote an opinion for John XXII on errors of the Spirituals. Smet, The Carmelites, 38-39. |

| ↑107 | For example, the text known as De Inceptione Ordinis, written around 1324, probably in France, explained that the Carmelites were the successors of hermits who had lived in Mount Carmel in the time of Elijah and Elisha. See Emmanuele Boaga, “La Storiografia Carmelitana nei secoli XIII e XIV,” in Land of Carmel: Essays in Honor of Joachim Smet, O. Carm., ed. Paul Chandler, O. Carm., and Keith J. Egan (Rome: Institutum Carmelitanum, 1991): 132. John Baconthorpe, English prior provincial from 1326-1333, wrote in the Speculum de institutione that Elijah and Elisha themselves were called Carmelites of the Madonna, as they had foreseen the coming of Christ, and that their successors had, after the incarnation, built an oratory dedicated to the Virgin on Mount Carmel. Boaga, “La Storiografia,” 134. |

| ↑108 | The area around Le Selve and Lastra a Signa also had a local connection to the traditions of eremitical life. Beata Giovanna da Signa had been born nearby around either 1242 or 1266, and at the age of 12 had decided to dedicate herself to the life of a hermit. Eventually entering a romitorio, she had the door walled in, and remained until her death in 1307. Miracles were attributed to her both while she was alive and after her death, and her feast was celebrated beginning in 1383. See Ragguaglio storico della beata Giovanna da Signa romita vallombrosana (Florence: Stamperia di Pietro Gaetano Viviani, 1741). |

| ↑109 | The plague of 1348 saw the death of many friars, who were then buried at Le Selve, according to the Florentine necrology. Among them were “Andreas Bonsi sacerdos” (April 16), “Philippus Ghimi sacerdos” (May 11), “Petrus Lapi sacerdos et confessor bonus” who also served as provincial (May 26). See Necrologium antiqum Conventuo Carmelitarum Florentiae, BNCF, Conv. Soppr. 785, 17v, 21r, 23v. For the chapter meetings, see Romagnoli, Selve, 22. |