Denva Gallant • Rice University

Recommended citation: Denva Gallant, “Memoria and the Spiritual Journey in the Thebaid Cycle at Santa Marta in Siena,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 12 (2025). https://doi.org/10.61302/CVNW3334.

Introduction

At the ex-convent of Santa Marta in Siena, a painted Thebaid, a genre of painting so called because they were thought to represent the eremitic life of fourth- and fifth-century Thebes, forms part of an intricate fresco cycle (Fig. 1).[1] The rocky, cavernous landscape, painted in a monochromatic palette, houses vignettes depicting scenes of eremitic life, including scenes from the Lives of the Desert Fathers.[2] In the Thebaid, every aspect of the monastics’ and the Desert Fathers’ lives is depicted, from the mundane to the miraculous. The vita contemplativa that the hermit saints embraced is exemplified in images of nuns warring with demons, a monk looking out over a body of water in deep thought, and Desert Fathers healing animals. Dizzying in its scope, the visual retelling of the lives at Santa Marta makes it difficult to read the fresco as a unified opus. This difficulty is compounded by the rocky landscape that houses the many narratives episodes within it. By physically separating the images, the rocky landscape suggests that each scene should be read in isolation as a self-contained lesson.

Fig. 1. Video of the Thebaid Cycle at Santa Marta in Siena, Benedetto di Bindo c. 1390-1410.

Painted throughout the Italian peninsula, most notably beginning in the fourteenth century, the Thebaids—or eremitic landscapes, as they might be more accurately called—are capacious in scope.[3] In addition to images from the Life of Anthony the Abbot and Paul of Thebes, the viewer might find an image of an anonymous hermit saint braiding a basket.[4] And while there is no standardization of the iconography within these eremitic landscapes, the seemingly haphazard arrangement of scenes is consistent throughout the genre. The viewer, it appears, is meant to read each scene separately. As Hans Belting observed of the landscape of the fresco cycle at Camposanto funerary complex at Pisa, “For all its embedded narrative, it does not claim of action or unity of space but offers a conceptual arrangement that organizes the many narrative units.”[5] Although Belting’s observations are aimed at the landscape as the primary driver of the conceptual framework, his arguments reflect a broader consensus within the scholarship about Thebaids, including the Thebaid at Santa Marta.[6] Looking primarily at how the vignettes would have reminded the viewer of past sermons or readings, other scholars have similarly read the images within the eremitic landscape at the Camposanto as disparate and singular, with the fresco having very little cohesive or unifying narrative structure.[7]

However, the fresco at the Augustinian monastery of Santa Marta in Siena invites a different interpretation. Reading the images through the lens of the spiritual journey, I argue that the pithy vignettes pictured across the Thebaid at Santa Marta form a cohesive and complex edificatory program that is activated by walking. Through the activity of walking, the nun embodies the role of the quester, a figure critical to the framing of the written Lives of the Desert Fathers. And through walking, an action that is thematized in the images within the fresco, the nun is encouraged to see the images not as disparate and isolated but, following the framework of the journey, as interconnected. United under this framework, the images at Santa Marta build synergistically on each other to form an edificatory program that encourages the viewer to reflect on their speech and actions using memoria, the act of not only recollecting concepts but also categorizing and synthesizing them. The viewer—like the questers seeking the Desert Fathers and Mothers—is guided towards a prelapsarian paradise, just shy of direct union with God.[8]

The eremitic landscape at Santa Marta has received little scholarly attention in comparison to the one at the Camposanto funerary complex and Fra Angelico’s Thebaid at the Uffizi.[9] The majority of scholarship has focused on dating and locating the literary sources for its sometimes enigmatic imagery.[10] Thomas Dittelbach has built on this foundational work by interpreting the fresco cycle as part of a larger Augustinian program that used monochrome palettes to make theological arguments and convey the order’s propaganda.[11] But like scholars who have written about other Thebaids, such as the one at the Camposanto, Dittelbach tends to treat the Thebaid at Santa Maria as a set of disparate and largely self-contained vignettes. Such readings, though valuable, have little to say about how the vignettes functioned together to enact a pedagogical program.[12]

This essay reads the seemingly disparate vignettes of the Santa Marta Thebaid as a cohesive narrative that led the viewer toward a spiritual destination.[13] In paying attention to the way this fresco functioned didactically, this study builds on a small body of work on the pedagogical orientation of other Thebaids. Considering the Thebaid at the Camposanto funerary complex in Pisa, Alessandra Malquori likens the vignettes to imagines agentes, images that summarize a thesis or theory in a small number of keywords or details.[14] The vignettes are meant to prompt the viewer to recall the story as heard previously in a sermon or as told during the evening collatio. Following Frugoni’s and Frojmovič’s studies, Lina Bolzoni has placed the fresco within the context of vernacular preaching in the early Renaissance, arguing that the work was part of the mnemonic “web of images” that, in her interpretation, constituted late medieval spirituality.[15] The present study contributes to this scholarship by showing how the didactic program of the Santa Marta Thebaid operated through a series of linked images that the viewer encountered while walking alongside the fresco in a prescribed direction. It discusses the pictorial conventions that invite the viewer to walk alongside the fresco and recall the Lives of the Desert Fathers, not in a haphazard way but in a methodical sequence, with a destination awaiting the faithful walker at the end. By analyzing the fresco at Santa Marta, this article models a new approach to Thebaids, showing that the images can be read not simply as a series of mnemonic devices, but also as sets of closely linked vignettes that reminded their viewers of the behavior necessary to draw closer to God.

The Thebaid at Santa Marta and the Mnemonics of Walking

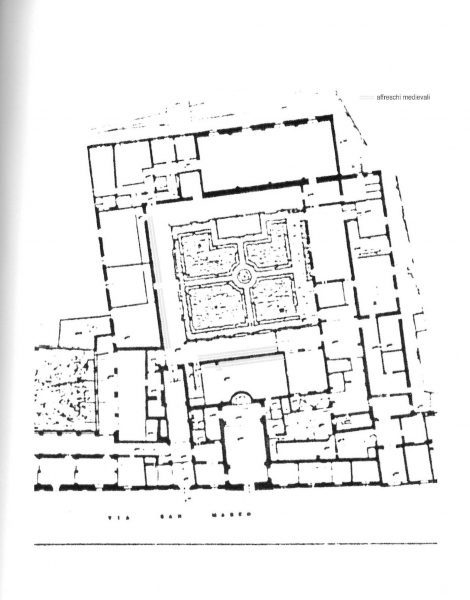

Fig. 2. Plan of the Santa Marta with the medieval frescos highlighted. The frescoes to the southwest of the cloister are of the Thebaid. Plan: Maria Corsi, Gli affreschi medievale in Santa Marta in Siena, 2005.

The Augustinian convent of Santa Marta in Siena was established in 1329 by Milla de’Conti d’Elci (Fig. 2).[16] While very little documentary evidence regarding the origins of the foundation survives, the act of the foundation exists.[17] In addition to the founding of a monastery in the borgo S. Marco dedicated to Santa Marta, the document requests that the women housed there follow the rule of St. Augustine and that they remain in clausura or enclosure, confined in cloistered spaces.[18] While the convent as a whole continued to grow with several modifications throughout the centuries following its foundation, the cloister, built in the fourteenth century, contains frescoes executed in the latter half of the century, including the Thebaid fresco, which is depicted on the southwest part of the cloister.[19] It is not clear who determined the program for the frescoes. Art historian Maria Corsi has suggested that the nun’s spiritual advisor, Jacomo di Luca, might have selected the stories from the Vitae patrum, The Lives of the Desert Fathers.[20] Attributed to Benedetto di Bindo in collaboration with other artists, the Thebaid fresco at Santa Marta was part of a burgeoning of images inspired by the Lives of the Desert Fathers in late medieval Italy.[21] However, despite the similarity in theme, the Thebaid at Santa Marta shares very little in the way of iconography with other notable Thebaids such as the fresco painting at the Camposanto in Pisa, attributed to Buonamico Buffalmacco, or the so-called Uffizi Thebaid, attributed to Fra Angelico. This is perhaps due to the fact that unlike many of the other Thebaids painted in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the Thebaid at Santa Marta was made exclusively for a group of women devoted to a religious life in enclosure.

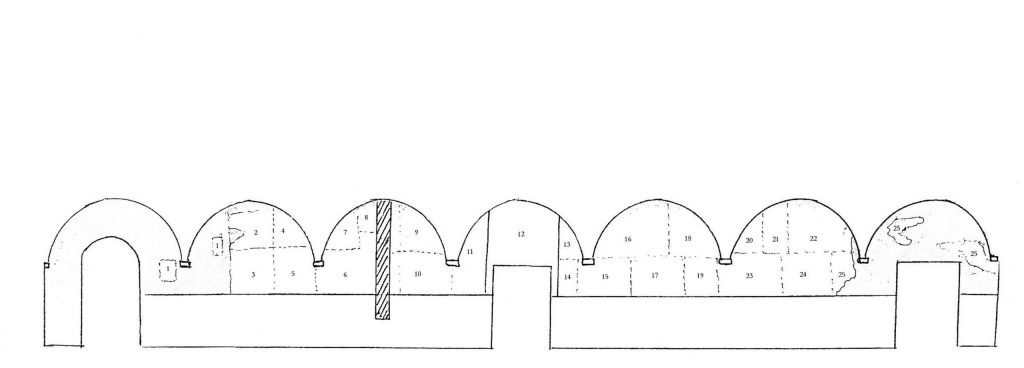

Fig. 3. The proposed diagram of fresco cycle of the Thebaid according to Maria Corsi. The following list corresponds to the numbers on the diagram. 1- Fragment of fresco cycle 2- Nun quieting a boar 3- Monks surround pig 4- Monk walking with pyx 5- Monk and angel encounter a corpse 6- Monk and angel encounter a rich nobleman 7- Temptation of Apellen 8- A monk reads 9- Serapion the Sindonite gives the gospel to a monk 10- Serapion is sold to pagans 11- Fragment of fresco cycle 12- Christ dead between two angels 13- Fragment of the scene of Paul of Thebes and Anthony the Abbot sharing bread 14- Paul of Thebe’s death 15- Paul of Thebe’s burial 16- The martyrdom of Potemia 17- Vision of the seven crowns destined for the obedient monk 18- Two nuns commit suicide 19- A nun eats lettuce 20- Hermit gives something to eat to a wolf 21- Monk eats meat 22- Monk refuses food while lying on a bed 23- Monk restores the sight of blind lion cubs 24- Monck in prayer between amongst ferocious beasts 24- Fragment of fresco cycle.

The eremitic landscape at Santa Marta includes vignettes inspired by various vitae and sayings in the Vitae patrum and other local hagiographical texts (Fig. 3).[22] The fresco added to the broader eremitical focus of the cloister. A pictorial cycle with scenes from the life of Saint Jerome, another notable eremitic saint, is still intact on the southeast part of the cloister. One can imagine a nun walking from the fresco cycle of the life of Saint Jerome, perhaps having contemplated the scene of the saint visited by an apparition in the desert, to the Thebaid cycle or vice versa. The pictorial cycles both reinforce the eremitical origin of the Augustinian order and create a space where the desert can speak in the middle of the city. What the viewer sees now, however, differs from what the nuns would have experienced in the fourteenth century. Originally, the fresco cycle occupied five lunettes, but in the course of renovations to the roof in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the cloister was rearranged and expanded, and two lunettes were added. In the fourteenth century, then, the image program would have had a more compact form and a more fluid progression than it does today.[23] As it is now, the fresco cycle begins and ends with fragments that create gaps in the narrative. Despite the regrettable loss of some of the images, the vignettes that remain still retain the animating principle of the fresco: a descent into the desert.

In its seemingly hodgepodge selection of scenes, the fresco at Santa Marta resembles manuscripts of the Vitae patrum. The Vitae patrum is an anthology of the lives of eastern Christian ascetics who inhabited the arid wastelands and deserts of Egypt, Palestine, and Syria during the fourth and fifth centuries.[24] The legends and maxims of the Desert Fathers and their disciples were first composed and circulated in Greek and Coptic. Several factors influenced the narratives’ transmission to the West, chief among them the success of Athanasius’ Life of St. Anthony, written in Greek in 357 and then quickly translated into Latin by both an anonymous author and Evagrius in 374. By the fifth century, manuscripts containing combinations of the Gelasian Corpus (the Lives of Paul of Thebes, Anthony the Abbot, Hilarion, and Malchus the Captive), the Historia Monachourm, the Historia Lausiaca, and the Collationes Patrum were being transmitted under the inclusive title of the Vitae patrum.[25] As texts continued to be produced and translated, the Vitae patrum expanded. Translations and recensions of the Apophthegmata patrum were slowly added to the corpora, as well as other vitae, such as the Life of St. Pachomius (translated into Latin by Dionysius Exiguus in the sixth century), the Life of Simeon the Stylite, the Life of Abraham the Anchorite, and women penitents and anchorites such as Pelagia, Thais, Mary of Egypt, and Mary, the niece of Abraham. By the Middle Ages, a manuscript referred to as a Vitae patrum could include any combination of the aforementioned texts. There was no standard compilation, and thus texts could be brought together in a variety of combinations and in different orders. The Thebaid at Santa Marta, then, is similar to the textual compilations of the Vitae patrum in that it presents a carefully chosen selection of scenes of the lives of the desert fathers, and it makes use of the genre’s flexibility by including some vignettes that are not usually associated with the Vitae patrum, such as scenes with no named protagonist and what appear to be scenes from local legends.[26]

The nuns at Santa Marta were almost certainly familiar with the Lives of the Desert of Fathers. Copied and produced in monasteries, the Vitae patrum was first and foremost a book for the cloister. In his Rule, written in the sixth century, Benedict of Nursia mentions the Vitae patrum as appropriate reading material for monks as they sat in silence after their meals, a practice that continued into the Middle Ages.[27] And in a late medieval French Vitae Sanctorum from a nunnery in Campsey, an inscription recommends the use of this text for reading at mealtimes.[28]

As the structuralist scholar Alison Goddard Elliot has observed and outlined, several of the vitae in the Lives of the Desert Fathers follow a central structural conceit that allows the reader to occupy the position of a traveler, journeying into the desert to witness the miracles of God and the virtuous behavior of the desert ascetics.[29] Often in the Lives, the narrator, a wandering monk, ventures alone into the desert to find men or women who surpass him in spiritual perfection. In The Life of Saint Macarius of Rome, for instance, three monks—Theophilus, Sergius and Hyginus—travel from their monastery in search of the place “where the sky meets the earth.”[30] Though it may seem that their goal is an invitation to engage in aimless wandering, they are actually motivated by what Alison Goddard Elliott calls “the more motif”: the desire to go in search for someone or something that surpasses the narrator in perfection.[31] The Life of Saint Macarius of Rome was an early addition to the corpus of the Vitae patrum and was frequently chosen for inclusion in compilations of the Lives. And the “more motif” that it features appears again and again throughout the Lives, in which various desert fathers and mothers undertake journeys in the hope of finding exemplars of spiritual greatness. Like the prototypical monk, the reader is an uninitiate who is “traveling” into the desert for the first time. Because she has not achieved the perfection of the desert father or mother, she is primed to identify with the questing narrator.

Fig. 4. Scenes from the Life of Macarius of Rome, Morgan MS. M. 626, New York Morgan Library and Museum, c. 1336.

If the reader is to identify with the quester, she must envision herself as traveling in some sense to the desert. The images of The Lives of the Desert of Fathers create the impression of movement in multiple ways.[32] As Otto Pächt famously argued in his The Rise of Pictorial Narrative in Twelfth-Century England, “Since pictorial form cannot move, ingenious devices have been developed for enlisting the onlooker’s help in supplying motion or movement, particularly in cyclical representations.”[33] In a fourteenth-century illuminated manuscript of the Vitae patrum (New York, The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.626), the viewer is made to feel the forward progression of the journey and to participate alongside it through directionality and the subtle positioning of the figures. For example, on folio 109v (Fig. 4), the previously mentioned questing monks— Theophilus, Sergius and Hyginus— are depicted in continuous narration traversing through a mountainous terrain. Continuous narration, a mode of pictorial narrative storytelling in which “successive episodes and characters are repeated within an ongoing space,” suggests movement through repetition and a flow of images akin to a stream of text, as Suzanne Lewis notes.[34] Continuous narrative is aided by directionality—the monk leading his two fellow companions points in the direction of the group of people, much smaller than the monks, and the smaller people move towards the left of the folio. Movement is seemingly halted by the river that bisects the terrain and divides the former scene from the next, but even here the wavy lines of the river draw the narrative and the viewer along to the following scene—of one of the monks grabbing herbs for nourishment. His directionality and that of his companions also point onwards to the left and to the turn of the page, a move that allows the viewer to continue on the journey with them. In the Morgan manuscript, these pictorial devices come together. The result is that the viewer is guided to travel alongside the questing saint.

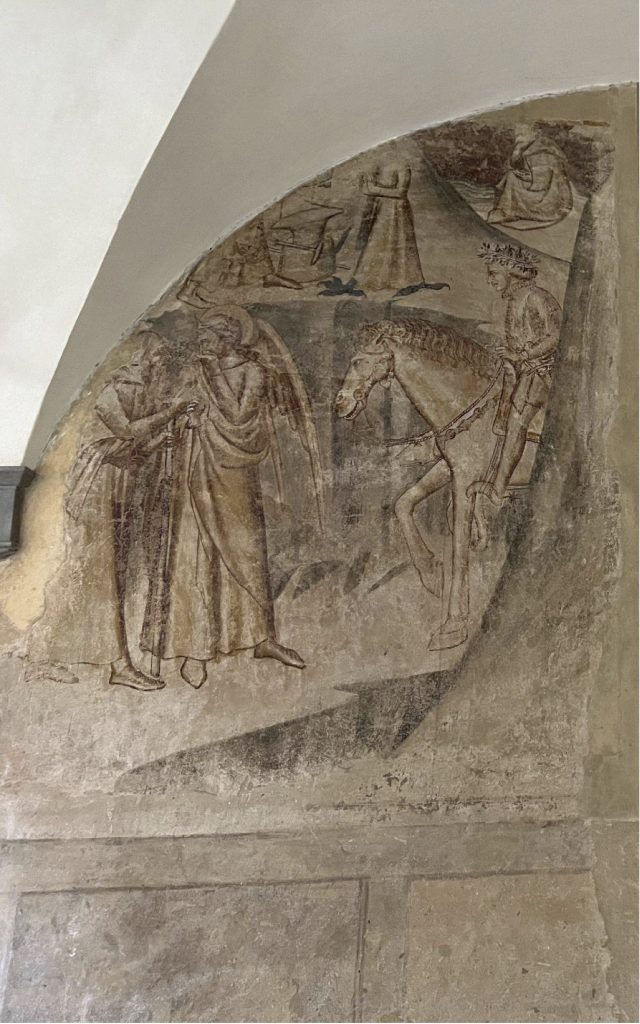

At Santa Marta, the viewer is called to embody the role of the quester by walking, a movement that is reinforced by the figures within the frescoes. Circumambulation was a key feature of monastic life in the cloister. Mary W. Helms, for instance, has written about weekly Sunday processions in monasteries, which usually began in the church and then moved around the east, south, and west walks of the cloister, before entering reentering the church for concluding rites.[35] As Helms notes, formal ambulation can be understood in part as a rite of purification that drove the unruly and ubiquitous demons from the monks’ living areas by imbuing with the walks the principle and power of cosmological order encoded in the formal organization of the procession.[36] While informal walks are not as well documented as these formal processions, the cloister was unquestionably a space of contemplative ambulation. In the fresco, figures such as the monk walking alongside an angel (Fig. 9) reinforce the very action that the nuns would have engaged in as they viewed the fresco from left to right, thus encouraging movement and directionality. As she imitated these figures, the viewer embodied the quester, seeking out knowledge from the desert ascetics. This imitation is both a mental and a physical posture: it consists of holding an image of the quester in the mind and practicing the quester’s movement with the body.

Walking also activated the functionality of the Thebaid, enabling the nuns to experience it as a meditational machine. As noted earlier, Malquori has argued that the images in frescoed Thebaids like the one at Santa Marta summon up key theological concepts with an efficient use of detail.[37] She has also argued that the images were connected to the resurgence in interest in the ars memorativa within monastic circles: each image would have called to mind the already-known story of a Desert Father.[38] Malquori’s description of the vignettes fits nicely with Mary Carruthers’ description of the mnemonic meditational devices used in late medieval monastic circles. Meditational machines, as Carruthers describes them, often took the form of architectural structures that the monk created in his mind to house ideas, arguments, and written passages that he would need to retrieve later.[39] Although the Thebaid at Santa Marta does not depict such an architectural structure, it functions as both a material mnemonic device and a meditational machine, housing vignettes that remind the viewer of previously heard narratives and offering them for further meditation. To use the Thebaid this way, though, the nuns had to gaze at the entire fresco—and that meant they had to walk alongside it.

The association between walking and meditation was already firmly in place in medieval Europe. In his comments on Psalm 41, St. Augustine paints a literary picture of the Tabernacle (the Church); it is in in this place, Augustine argues, that one discovers the way to the house of God.[40] In his description of the pathway to God’s house, through the tabernacle, walking is essential:

When I poured out my soul within me in order to touch my God, how did I do this? ‘For I will enter [ingrediar] into the place of the Tabernacle.’ These words suggest that I will first blunder about in [errabo] outside the place of the Tabernacle seeking my God…And now I will look with many things in the Tabernacle…Faithful men are the Tabernacle on earth; I admire in them their control over their members, for not in them does sin reign by obedience to their desires, nor do they show off their limbs armed with the sins of inquity, but show them to the living God in good works; I marvel at the discipline physique of their soul in service to God. I look again upon the same soul obeying God, distributing the fruits of his activities, restraining his desires, banishing his ignorance…I gaze upon those virtues in my soul. But still I walk about in the place of the Tabernacle…[41]

In Augustine’s meditation, his mnemotechnical walk through the structure is essential to gleaning the spiritual concepts housed in the tabernacle. He first blunders outside the tabernacle but then enters and is moved by the faithful men housed there.[42] Looking, gazing, and marveling at the faithful men are all facilitated by walking—a point that Augustine gently reminds us of when he writes, “But still I walk.” Circumambulating the place of the tabernacle, gazing upon the admirable self-control the faithful men of the tabernacle have over their members, Augustine is called to reflect upon the same virtues in his soul, an introspective act of self-reflection that ultimately leads him to the house of God. Augustine’s meditation on the tabernacle hints at the importance of movement, specifically walking, in the viewing of the Thebaid at Santa Marta. Much like the tabernacle, the Theban desert houses faithful men (and women) from whom the female monastics can learn by walking and viewing the imagines agentes.

But the walking encouraged by the Thebaid at Santa Marta is not aimless movement. Rather, it is an ordered movement that leads to a goal.[43] In this respect, it has much in common with the rhetorical device known as ductus, which Mary Carruthers defines as denoting “an ordered, directed motion—such as practiced movement of the human limbs.”[44] Augustine famously evoked ductus in his commentary on Psalm 41, in which he discusses the tabernacle as a space he must pass through in order to arrive at his final destination, the house of God. There is a certain sweetness, an “interior music,” that leads the Psalmist through the tabernacle to the house of God.[45] Augustine describes it as “some kind of organum” that sounded sweetly all through the house of God.[46] In Augustine’s meditation on the psalm, music serves as a metaphor for the ductus of the tabernacle. As Paul Crossley, looking at Chartres Cathedral, puts it, the ductus of a medieval object or architecture is its “flow, movement, direction,” the element that leads the viewer in and around it, often facilitated by liturgy and the design of the work.[47] Others see ductus as more physically directional, a set of instructions given by the features of an object.[48] Ductus, in short, guides the viewer, inviting them to engage with either an object or architecture in a relatively prescribed manner.

At Santa Marta, it is debatable whether the fresco creates ductus in the sense of providing a set of instructions about physical behavior. What it does do, however, is encourage walking—and walking in a particular direction, starting with the first vignette and continuing to the end. The vignettes are placed in a way that not only guides the steps of the female monastic viewers but also unifies the images so that a pathway appears, leading the viewers like the sweet music of the tabernacle. The act of walking along this pathway allows the viewers to see the fresco as an edificatory journey during which each vignette leads them one step closer to God.

Walking the Thebaid: Perfected Speech, The Limitations of the Corporeal Senses, and Spiritual Care

Fig. 5. Suicides of Two Nuns, Thebaid Cycle at Santa Marta in Siena, Benedetto di Bindo c. 1390-1410.

Rather than being loosely associated through the source material, the images at Santa Maria build on one another, with the theme of one image leading to the next, culminating in an image that expresses the preceding tenets in a single moralizing tale. As the female monastic viewers walked alongside the Thebaid fresco at Santa Marta, they were encouraged to monitor their thoughts, speech, and corporeal senses and to pursue a life of the spirit in a caring community. These tenets, cultivated throughout the nun’s peripatetic journey, are expressed simultaneously in the final moralizing tale of the suicide of two nuns (Fig. 5), where the foundational principles find exemplification in a negative exempla. That image of the suicides serves as a hinge between the mundane world in which corporeal sight is to be questioned and a prelapsarian land where the miraculous occurs and man is reunited with animals. Just beyond the narrativization of suicide, paradise waits in the shape of a forested, prelapsarian landscape. It is by this path that one is led further into the desertum and closer to God.

Fig. 6. First Lunette, Scenes from the Lives of the Desert Fathers, Thebaid Cycle at Santa Marta in Siena, Benedetto di Bindo c. 1390-1410.

Fig. 7. Nun quieting a boar, Thebaid Cycle at Santa Marta in Siena, Benedetto di Bindo c. 1390-1410.

Due to the degraded state of the frescoes, it is impossible to know what image would have begun the nun’s journey. However, the first lunette that contains legible vignettes of the fresco cycle (Fig. 6) presents the viewer with the foundational tenets of the narrative, highlighting the importance of interrogating one’s thoughts and speech. The former is foregrounded in the arresting vignette of a nun standing on top of a boar (Fig. 7).[49] This is no ordinary boar: the flames issuing forth from his mouth and anus indicate that he is a demon. In the Lives of the Desert Fathers, the Devil and his demons often visit the desert saints and their apprentices in the form of a phantasm, a term used at the time to refer broadly to simulacra of things in the material world, including humans and animals.[50] The boar was often associated with debauchery and destruction, a complete irreverence for the sacred. In Psalm 79, it is the boar that lays waste to the vineyard that God creates for the Jews after their exodus from Egypt.[51] In the Middle Ages, it also personified lust; the animal is sometimes depicted as trodden underfoot by a personification of chastity.[52] The meaning of the image is clear: the nun has achieved victory over the phantasmic boar.

Standing over the boar, the nun leans over slightly. With one hand she brings her index finger close to her lips, and with her other, she points down at the boar. With this gesture, the nun compels the boar to silence, an act that suggests that the boar’s interference is audible. Demons, presenting themselves to the mind in the form of a phantasm, often plagued monks and nuns with unholy thoughts. To monastics, demons were more than physical forces; they were voices constantly inviting them to sin. In his On Prayer, the Christian theologian and monk Evagrius Ponticus described this condition, sometimes referred to as a besiegement, as the mind being “surrounded by a phalanx of thoughts or representations,” which came from demons.[53] The nun conquers the demonic phantasmic boar by silencing him, effectively shutting down the thoughts he instills in her mind. The image, as an exemplar, offers a strategy to its monastic viewers: if a woman wants to triumph over the Devil, she must silence that voice within her before she succumbs to temptation.

Fig. 8. Monks surround pig, Thebaid Cycle at Santa Marta in Siena, Benedetto di Bindo c. 1390-1410.

As a moral exemplar, the story cautions against careless, ill-defined speech. The second image (Fig. 8), located beneath the image of the sainted nun silencing the boar, builds on the concept of guarding one’s speech but moves the locus of surveillance from inner dialogue (thoughts) to verbalized expression (the spoken word). Nestled in the lower portion of the craggy mountainside, the image shows three monastics engaged in conversation. At the center of their circle, a pig sits with its snout pointed towards the male monastic who speaks. There is an uncanny mimicking between monastic and pig—both the monastic and the pig have their mouths open, and their gestures, the monk’s hand raised and the pig’s foreleg raised ever so slightly, are similar as well. The connection between the pig and the monastic can be explained to a certain degree by the vita from which the image draws inspiration. In the Sayings of the Desert Fathers, the anonymous narrator relates that there was a holy senior to whom Christ had given the gift of being able to see what others could not.[54] When he watched a group of brethren talking about the holy scriptures, he would see a crowd of holy angels around them. However, when they discussed something that was disappointing to the angels, he would see pigs, “miserable specimens,” “full of disease cavorting among them.”[55] The pigs, of course, are demons. In the image, then, the pig’s mimicking of the monastic is a sign that the monastic’s speech is spiritually impure. Taken as a whole, the image reminds its viewers to mind their speech, a tenet that corresponds to the one expressed in the vignette of the sainted nun.

The images of the nun triumphing over the demonic boar and the monastics encircling the pig express foundational tenets of the edificatory program—the female monastic viewer should be mindful of her thoughts and speech. In revealing that one’s thoughts and speech might both originate from the demonic and call the demonic into existence, the images encourage a surveillance of both the interior self and outward behavior. For the Desert Fathers, diakrisis, or the gift of discernment, was the ability to detect and clearly “see” the intangible spirits that registered in the psyche in the form of thoughts and images.[56] In his Life, Anthony demands that a monk acquire the ability to distinguish between spirits, urging his disciples to ask the Lord to grant them the capacity to see through demons’ tricks.[57] In order to be led by virtue and not by sin, a mining of the self was key for the both desert father and medieval monastic. The two vignettes encourage such self-examination through the negative leitmotif of the demonic, as epitomized by the pig and its cognates. The pig and boar connect the seemingly disparate scenes, creating both a spatial and a thematic relationship along the craggy landscape through their visual and species-specific affinity. In both scenes, pigs are visual signs of an inner condition. Through the careful juxtaposition of the vignettes and the repetition of a visual topos, the fresco forms a cohesive pathway that leads the female monastic along her journey.

Fig. 9. Monk and angel encounter a corpse, Thebaid Cycle at Santa Marta in Siena, Benedetto di Bindo c. 1390-1410.

Fig. 10. Monk and angel encounter a rich nobleman, Thebaid Cycle at Santa Marta in Siena, Benedetto di Bindo c. 1390-1410.

Just as the previous images encourage self-monitoring, so too do the images that follow, focusing the female monastic viewer’s attention on the limitations of the corporeal senses. Told over the span of two images, the vignette depicts the story of a man’s encounter with two angels in the desert (figs. 9 and 10).[58] The first image shows a monk walking alongside an angel (Fig. 9), his hand held to his nose. The reason for his discomfort is clear: a dead body covered with leaves and branches lies before him. Oddly, though he encounters the same body, the angel does not hold his nose but rather raises his hand towards the traveling monk. In the second image (Fig. 10), separated by the first by a pilaster, the roles are reversed. The angel holds his nose, suggesting a reeking odor, while the monk points in the direction of a nobleman dressed in finery who approaches the pair. The vignette reveal the limitations of the corporeal senses. Whereas the monk is offended by the reek of a dead corpse, the angel is more offended by the “smell” of the nobleman. In the written narrative, the angel explains his lack of reaction to the corpse by telling the monk that angels cannot smell the odors of the world but they do register the smell of sinners. The image calls attention to the reek that emanates from the soul of a sinner, a smell that is undetectable by human senses but very much apparent to the senses of spiritual beings. In Christian thought, the corporeal senses (sight, smell, taste, hearing, touch) are measured against their antithesis, the spiritual senses—those faculties often referred to as the soul, the heart, or the intellect (mens) that allows one to “see” and know God in the material world.[59] Although the corporeal senses are able to help a person navigate the material world, they have limitations. Augustine notes, for instance, that the bodily senses cannot aid man in making moral judgments.[60] At Santa Marta, the vignette of the monk and angel calls attention to the limitations of the corporeal senses: they are not reliable arbiters of spiritual virtue, unable as they are to detect the fetid smell of a sinful soul. This vignette suggests that just as the monastic should monitor her speech and thought, so too should she monitor her corporeal senses, which cannot detect the true nature of a soul.

Fig. 11. Scenes from the life of Serapion the Sindonite, Thebaid Cycle at Santa Marta in Siena, Benedetto di Bindo c. 1390-1410.

When the nuns of Santa Marta entered the cloister, they took a vow of poverty.[61] Attachment to material goods led to corruption of the soul, an idea exemplified by the nobleman. Its critique of wealth as morally corruptive links the vignette to the one that follows, with thematic cohesion created through the evocation of the rejection of attachment to the material and nonspiritual. The pictorial life of the holy father Serapion the Sindonite plays out over the course of four scenes in the top and bottom registers of the rocky landscape (Fig. 11).[62] Though the narrative has been cut off on the left, it is still possible to discern the story of the sainted father who gives away all of his worldly possessions and finally offers himself up. On the top left, a man is shown receiving a tunic, a reference to Serapion’s giving his cloak and tunic to a poor man; the following scene shows Serapion dressed in his undergarments giving a monk a book, a reference to the moment in the narrative when Serapion gives away his copy of the Gospels. On the lower left, a monk gestures to a figure that is no longer visible, perhaps a reference to a monk inquiring about the Gospels, to which Serapion responds that he has sold the very thing which told me to sell all that I have and give it to the poor.[63] The final scene, in the lower right quadrant of the lunette, shows Serapion being sold into slavery by a woman who receives payment from a man in an elaborate headdress. In the written narrative, the narrator relates that finally, with no worldly possessions to his name, Serapion allows himself to be sold into slavery by a poor woman to whom he had no alms to give. Through this narrative, the nun is called to remember Christ’s words to the rich man: “If you want to be perfect, go, sell your possession and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven. Then come, follow me.”[64] As a foil to the nobleman in the previous vignette (Fig. 10), Serapion is an important exemplar to the female monastics at Santa Marta who have chosen to reject the material and worldly in pursuit of a holy life.

Fig. 12. Scenes from the Life of Paul top and bottom left of lunette, Thebaid Cycle at Santa Marta in Siena, Benedetto di Bindo c. 1390-1410.

Fig. 13. Bottom right, Anthony buries Paul; top left, suicide of two nuns, Thebaid Cycle at Santa Marta in Siena, Benedetto di Bindo c. 1390-1410.

When viewed together, the images of the nobleman and of Serapion pose an implicit question: When we reject the material world, what should we seek instead? The images that follow answer this question with scenes from the Life of Paul of Thebes (figs. 12 and 13), presented in a way that seems tailored for viewers who lived in community. For the nuns at Santa Marta, the rejection of all that was worldly and profane had to involve care for each other as a fundamental part of the pursuit of devotion to God. And indeed, although the Life of Paul is purportedly the tale of the origins of the eremitic life, the scenes from the Life emphasize the importance of fellowship and care.[65] While some of the scenes at Santa Marta are damaged and truncated because of the construction of the vault, it is possible to identify scenes through comparison to other pictorial cycles depicting the Life of Paul, such as those found in contemporary frescoes and illuminated manuscripts.[66] Although we can make out only one figure (Fig. 12), an older monk holding his hand out as if to receive something, the scene in the top right corner is identifiable as the moment in the life when Anthony and Paul share bread delivered by a raven. In the lower right corner of the lunette is an image of Paul’s death. The saint, dressed in his landmark palm fronds and holding his hands in prayer, kneels upright, ready to be buried. In the following lunette (Fig. 13), Anthony is shown burying Paul, holding his head reverently and gently lowering him into the grave. There is a tenderness in Anthony’s treatment of Paul, the most revered of the Desert Fathers during their era and arguably in the centuries following.[67] In the written narrative, lions bury Paul, the miraculous act a sign of God’s favor. The transfer of the act to Anthony shows his care for his fellow hermit. It hints at a brotherhood in the unforgiving desert where Paul and Anthony have chosen to face their thoughts and demons alone. The brotherhood that Anthony and Paul share as eremitic saints is also intimated in the first scene, where the breaking of bread exemplifies the fellowship enjoyed in the cenobitic life; it is both eucharistic and communal at once.

In its focus on fellowship and care, the image of Anthony and Paul sharing bread and Anthony’s burial of Paul may well have resonated with the Augustinian nuns. The nuns of Santa Marta followed the Rule of Saint Augustine as established in their charter.[68] Citing the Acts of the Apostles, “they had all things in common and distribution was made to each one according to each one’s need,” (4:32,35), the Rule places special emphasis on communal ownership and sharing to guard against greed and attachment to material possessions.[69] The requirement to share extended to food, another point emphasized several times in the Rule. This emphasis finds pictorial weight in the image of Paul and Anthony, where their sharing of the bread speaks to community, care and fellowship, a coming together of two individuals in communion sharing the great wealth of the bread. (Paul relates to Anthony that for sixty years, he received only a half a loaf of bread, but when Anthony arrives, that quantity—thanks to the miraculous provision of God—is increased to a full loaf.)[70] The image, then, reinforces an important aspect of the Rule and holds it up as a virtue to the nuns.

The images depicting scenes from the Life of Paul present the nuns at Santa Marta with positive exempla of fellowship and proper care for one’s spiritual brother or sister. Yet in the same lunette (Fig. 13), a positive exemplum is contrasted with a negative one. At the upper right edge of the lunette, two nuns are depicted having committed suicide in a forested landscape: one floats lifeless in the river while the other hangs from a tree.[71] From the doorway of a building, two more nuns look at the tragedy in shock. The image depicts scenes of a disastrous chain of events that have been set in motion by malicious gossip. A nun, we are told in the Vitae patrum, had engaged in innocent conversation with a shoemaker who was looking for work. The conversation was seen from afar by a second nun, who, inspired by the devil, began to tell others about the first nun’s supposed impropriety. Although she had committed no dalliance, the first nun, unable to bear the shame of the slander against her, drowned herself in a nearby river. The second nun, whose words had led to the death of her sister, was horrified and in recompense hanged herself from a tree. The story acts as a clear warning against the appearance of impropriety, but more importantly, it cautions against a certain form of speech: gossip. The second nun’s unguarded and unchaste speech led to two deaths. If she had minded her tongue and focused on scripture, neither of the two nuns would have committed the grievous offense of suicide.

The image of the suicides reminds the viewer of all the edifying lessons conveyed up to this point by the linked chain of vignettes. The image reminds its audience of Augustinian nuns that their language must be guarded and virtuous. This is a principle introduced in the images of the nun who silences the boar and the pig surrounded by monks—malicious gossip has its origins not only in spoken words but also in thoughts and interpretations. The image of the suicides also reminds the nuns of the limitations of the corporeal senses, especially sight. As the image of the monk with the angels reminds us, the corporeal senses are not to be trusted without question, as they cannot judge the goodness of another’s soul. Finally, the image demonstrates what can happen when community and care are not at the forefront of the nuns’ spiritual practice. If the images of the monk with the two angels and Serapion charge the nuns to reject the worldly and material in favor of a life devoted to God, this image shows how that pursuit can break down without the care and community lauded in the images depicting scenes from the Life of Paul of Thebes.

There are remarkably few representations of suicide from the Middle Ages, although images of Judas hanging himself are an exception.[72] The representation of suicide in the fresco cycle at Santa Marta is alarming and arresting because of both its rarity and its compositional force. Occupying the upper right register of the lunette, the scene sits as a juxtapositional counterweight to the image of Anthony’s burial of Paul.[73] The dynamic opposition draws attention to the two different types of death depicted—one noble, followed by a proper burial given with care, and the other unceremonious and egregious, lacking the care of the community. In their striking juxtaposition, the images tell the nuns that a lack of community and care may lead to a grievous sin. The nuns who look out in shocked amazement at the scene before them stand in opposition to Anthony, who gently lays Paul into the ground. No such tenderness is afforded to their dead sisters, who rely on the tree and the river to cradle their bodies. They have given away to despair, much as Judas has in depictions of his suicide. The absence of a proper burial is a consequence of words spoken with no attention to the limits of the corporeal senses. In an intense appeal to memoria, the nuns’ suicide brings together the edificatory principles expressed thus far—with this negative exemplum, the viewer is reminded to interrogate her senses, to be mindful of the limitations of the corporeal senses, and to renounce worldly attachments.

As the viewer walks alongside the Thebaid fresco, traversing the rocky environment alongside the figures, the landscape changes. The suicide of the two nuns introduces new elements—a fast-moving river and trees that canopy the landscape. Rivers are important divisional barriers within medieval literature and images. In the Life of Mary of Egypt, the questing saint Zosimas travels to the river Jordan in his quest to find that person in the desert more perfect than himself, traversing it in his longing to find Mary of Egypt.[74] In the Life of Macarius the Roman, the three monks—Theophilus, Sergius, and Hyginus—meet at the Euphrates river to discuss their desire to go “where the sky meets the earth,” and when their journey is decided upon, m they cross the river Tigris in order to begin it.[75] Rivers are also powerful bodies that mark and initiate transitions. It is in the river Jordan that Christ is baptized by John, ritually cleansed; when he exits the water, the heavens are open to Him and he sees the Spirit of God descending as a dove, and coming upon Him (Mt 3:15-17). The dove that lands in the river ahead of the nun may refer to the Holy Spirit and a need to repent, but the river itself serves a powerful liminal and transitional device that moves the reader from the earthly realm to a place just short of paradise. As the viewer follows the river towards the next lunette, she is led to a landscape populated with trees and animals, a new land that evokes a prelapsarian ideal.

Fig. 14. Desert Father restores the sight of lions cubs, Thebaid Cycle at Santa Marta in Siena, Benedetto di Bindo c. 1390-1410.

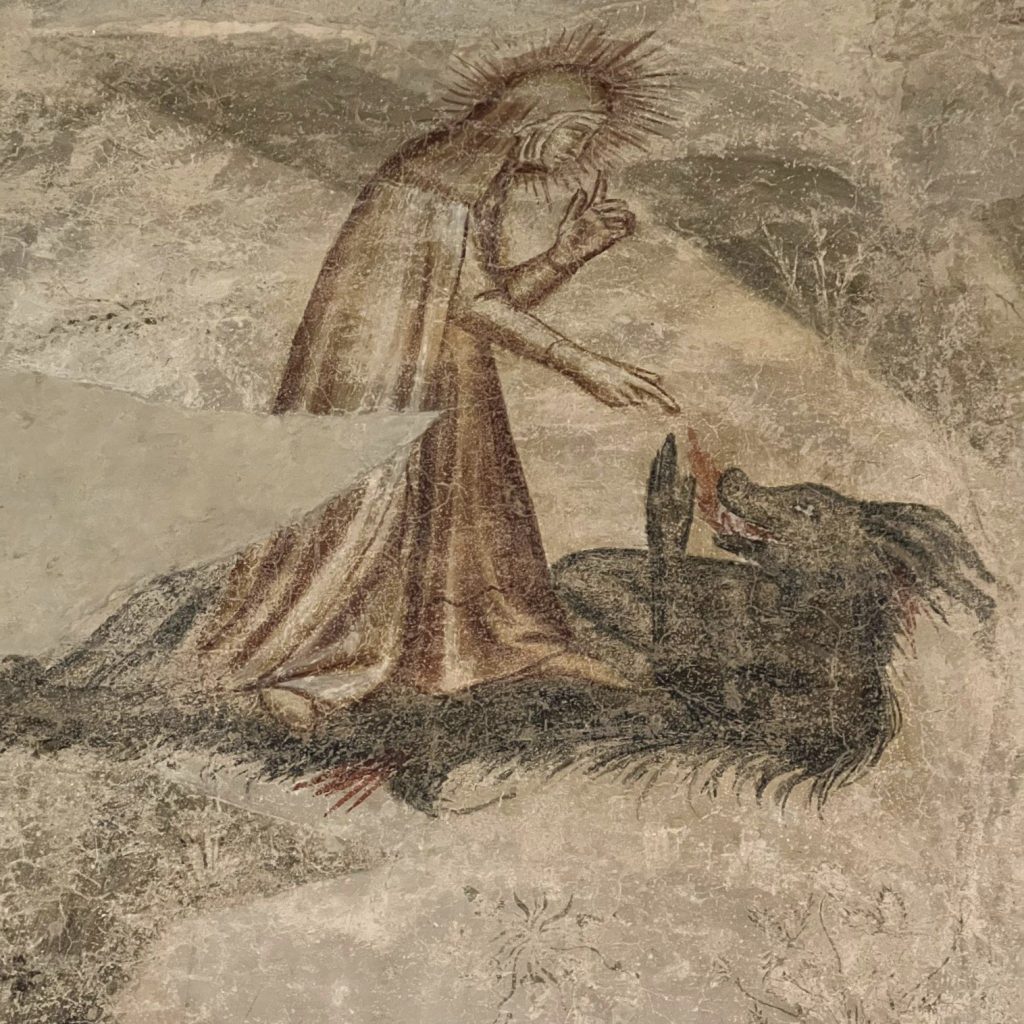

That the viewer has moved closer to paradise is confirmed by the vignette of the desert father restoring the sight of the lions (Fig. 14). In the lower left register of the final lunette of the Thebaid fresco cycle, a Desert Father leans down to touch the eyes of a lion cub that approaches him while its mother and littermates draw near as well. The image takes its inspiration from a story told in Severus Sulpitius’ Dialogue in which a monk who notably lived far in the desert—it takes seven months for the questers to find the Desert Father—comes upon a lioness and her cubs who are blind.[76] In the written narrative, the monk knows exactly what the lioness desires. Calling upon the name of Christ, he touches the cubs’ eyes and their sight is restored. In the image, this seemingly easy communication between desert father and lion is communicated through touch, the lion cubs yielding to the monk as if domesticated. The restoration of the cub’s sight, of course, is not due to any innate power of the Desert Father but to God’s favor. Nevertheless, the image speaks to a reclamation of a prelapsarian ideal where man and beast lived in harmony. It represents a shift in the topography, not only in terms of the physical landscape—it is now marked by more trees and caves than before—but also in terms of the spiritual landscape. The female monastic viewer has arrived just shy of paradise.

The idea that movement away from civilization and the mundane equals a closeness to paradise is affirmed in written narratives of the Desert Fathers as well. In the Life of Macarius, the sainted desert father’s holiness is measured not only by the miracles that God is able to perform through him but also by his distance from the inhabited, mundane world.[77] The questers and narrators of the Life remark that Macarius appeared to them at the twentieth milestone from Paradise. His closeness to God is not simply spiritual and thus intangible but physical as well; nearer to paradise, Macarius is nearer to God. His nearness to God and paradise is also marked by his reclamation of a prelapsarian ideal—Macarius has two lions who are his companions. He has raised them, Macarius tells the questers, since they were cubs and their mother died. Macarius assumption of the role “mother” to the two lions demonstrates his acceptance into a new order of things—a rejection of civilization’s imperative to procreate sexually and instead a move to generate asexually as the eremitic life encourages.[78] The kinship forged between Macarius and the lions also indicates how far he has traveled from the mundane world, where interspecies relationships (between man and apex predator such as a lion) are impossible.

Encouraged by the peripatetic desert saints who walk in images alongside her, the nun embodies the quester, looking for and finding faithful men and women from whom she learns. The physical juxtaposition of the vignettes and their thematic connections create the ductus that leads to God. The nun learns on her journey the importance of interrogating her thoughts and speech, the limitations of the corporeal senses, and the value of community. The culminating scene is a moment of tragedy that brings together the lessons of the previous vignettes and changes the physical and spiritual landscape. The scene of the suicides is a reminder that the path towards God requires a continual control over the spirit. And while the nun herself might not be able to witness the prelapsarian paradise in her daily life, she can see what she must aspire to.

Conclusion

The Thebaid at Santa Marta provides the viewer with an edifying narrative spread across its rocky landscape. Though the landscape provides meaningful divisions, it does not prevent a reading of the pictorial narrative as cohesive and unified. Taking on the position of the quester, a positionality encouraged by the figures that walk through the landscape, the nun embarks on a journey that unites the vignettes in its purpose. The concept of the spiritual journey draws together the seemingly disparate vignettes, while the ductus of the fresco, or the thematic connections that link one vignette to the next, reinforce the sense of a path.

Reading the Thebaid at Santa Marta as a work that has ductus and a goal suggests a new approach to analyzing eremitic landscapes. As I have shown, fresh insights can emerge if we regard the works not as haphazardly arranged, but as programs that edify the viewer in their totality. This approach offers a way for the contemporary scholar to understand how the eremitic life exemplified in these landscapes might have instructed the God-seeking viewer. For instance, if we want to explore the extent to which the Thebaid at the Camposanto may be a cohesive narrative, we might begin by seeing it as leading the viewer on a spiritual journey. Beginning at the bottom of the fresco, the area that is more mundane and earthly, the viewer could navigate a path upward to the pinnacle, where miracles and union with Christ are visualized.[79] Reading the vignettes as connected in thematic focus allows for a path to appear, one that guides the viewer to understand the eremitic life not as a series of disconnected attitudes and behaviors but as a series of steps toward God. In sermon 170, Augustine urges the faithful, “Walk securely in Christ without anxiety; walk. Don’t stumble, don’t fall, don’t look back, don’t stick on the road, don’t wander away from the road. Only beware of all these things, and you have arrived.”[80] Though Augustine’s words here may be taken metaphorically, the injunction may have rung true for the fourteenth-century viewer of the Thebaid: if they followed the path, then they too might arrive at the long-desired union with God.

References

| ↑1 | My many thanks to Alison Perchuk and Beth Williamson for their thoughtful feedback on this article and Amelia Hope-Jones for her constant support.

For the most comprehensive bibliography on Santa Marta, see Maria Corsi, Gli Affreschi Medievali in Santa Marta a Siena: studio iconografico (Siena: Cantagalli, 2005). Ellen Callman was the first to define the genre in her landmark study, Ellen Callman, “Thebaid Studies,” Antichità Viva 14 (1975): 3–22. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | For a full list of the scenes included in Thebaid fresco at Santa Marta, see Corsi, Gli Affreschi Medievali in Santa Marta a Siena: studio iconografico. On images of the Desert Fathers in the late Middle Ages, see Denva Gallant, Illuminating the Vitae Patrum: The Lives of the Desert Saints in Fourteenth Century Italy (University Park: Penn State University Press, 2024); Alessandra Malquori, Laura Fenelli, and Manuela de Giorgi, eds., Atlante delle Tebaidi e dei temi figurativi (Florence: Centro Di, 2014). |

| ↑3 | Amelia Hope-Jones advocates for the more inclusive term eremitic landscapes over Thebaid, as the term eremitic landscape does not relegate the theme to a particular time or place. Since the fresco at Santa Marta has been identified as a Thebaid in scholarship, I will refer to it as such here. Amelia Hope-Jones, “Images of the Desert, Religious Renewal and the Eremitic Life in Late-Medieval Italy: A Thirteenth-Century Tabernacle in the National Gallery of Scotland” (Ph.D., The University of Edinburgh, 2019), 23–25. |

| ↑4 | See the eremitic landscape at the funerary complex at the Camposanto in Pisa. For the most comprehensive bibliography on the Thebaid at Camposanto, see Chiara Frugoni, “Altri luoghi, cercando il paradiso (Il ciclo di Buffalmacco nel Camposanto di Pisa e la committenza domenicana),” Annali della Scuola normale superiore di Pisa. Classe di lettere e filosofia 18, no. 4 (1988): 1557–1643; Eva Frojmovič, “Eine gemalte Eremitage in der Stadt: Die Wüstenväter im Camposanto zu Pisa,” in Malerei und Stadtkultur in der Dantezeit: die Argumentation der Bilder, ed. Hans Belting and Dieter Blume (Munich: Hirmer, 1989), 201–14; ”; Alessandra Malquori, “Luoghi e immagini nelle storie degli anacoreti di Pisa”; Lina Bolzoni, The Web of Images: Vernacular Preaching from Its Origins to Saint Bernardino da Siena (Burlington: Ashgate, 2004), 97–104. On the Camposanto complex in general see Clara Baracchini and Enrico Castelnuovo, eds., Il Camposanto di Pisa (Torino: Einaudi, 1996). See also the essays in this special issue. |

| ↑5 | Hans Belting, “The New Role of Narrative in Public Painting of the Trecento: ‘Historia’ and Allegory,” Studies in the History of Art 16 (1985): 162. |

| ↑6 | Frugoni, “Altri luoghi, cercando il paradiso (Il ciclo di Buffalmacco nel Camposanto di Pisa e la committenza domenicana),”; Alessandra Malquori, “Luoghi e immagini nelle storie degli anacoreti di Pisa,” in “Conosco un ottimo storico dell’arte …”: per Enrico Castelnuovo: scritti di allievi e amici pisani, ed. Enrico Castelnuovo, Maria Monica Donato, and Massimo Ferretti (Pisa: Edizioni della Normale, 2012); Corsi, Gli affreschi medievali in Santa Marta a Siena: studio iconografico. |

| ↑7 | Frugoni, “Altri luoghi, cercando il paradiso (Il ciclo di Buffalmacco nel Camposanto di Pisa e la committenza domenicana),”; Alessandra Malquori, “Luoghi e immagini nelle storie degli anacoreti di Pisa.” |

| ↑8 | On the reclamation of a prelapsarian ideal in the Lives of the Desert Fathers, see Alison Goddard Elliott, Roads to Paradise: Reading the Lives of the Early Saints (Hanover and London: Brown University Press, 1987). |

| ↑9 | For the most recent bibliography on the so-called Uffizi Thebaid, Alessandra Malquori, “La Tebaide degli Uffizi,” in Atlante delle Tebaidi e dei temi figurative, eds. (Florence: Centro Di, 2014) Alessandra Malquori, Laura Fenelli, and Manuela de Giorgi, 33–38. |

| ↑10 | Corsi, Gli affreschi medievali in Santa Marta a Siena: studio iconografico; Maria Corsi, “Il ciclo eremitico di S. Marta a Siena,” in Santità ed eremitismo nella Toscana medievalae. Atti delle giornate di studio (11-12 giugno 1999), ed. Antonio Gianni (Siena: Cantagalli, 2000), 89–107; Maria Corsi, “Le agostiniane di Santa Marta a Siena,” in Per corporalia ad incorporalia. Spiritualità, agiografia, iconografia e archittetura nel medieovo agostiniano, ed. Centro Studi “Agostino Trapè” (Toletino: Biblioteca Egidiana, 2000), 233–42; Bram de Klerck, “Het heremietenideaal in de Toscaanse schilderkunst van het Tre- en Quattrocento,” Millennium 4–6 (1990): 121–36; Bram de Klerck, “Heremieten in Lecceto En de Augustijner Oder Traditie,” Kunstlicht, 1989, 11–16; Thomas Dittelbach, “‘Nelle distese e negli ampi ricettacoli della memoria’. La monocromia come veicolo di propaganda dell’ordine mendicante degli Agostiniani,” in Arte e spiritualita nell’ordine agostiniano e il convento di San Nicola a Tolentino, ed. Graziano Campisano (Roma: Argos, 1994), 101–5. |

| ↑11 | Dittelbach, “‘Nelle distese e negli ampi ricettacoli della memoria’”; Thomas Dittelbach, Das monochrome Wandgemälde. Untersuchungen zum Kolorit des frühen 15. Jahrhunderts in Italien (Hildesheim-Zürich-New York: Georg Olms Verlag, 1993). |

| ↑12 | Belting, “The New Role of Narrative in Public Painting of the Trecento: ‘Historia’ and Allegory”; Chiara Frugoni, “Altri Luoghi, Cercando Il Paradiso (Il Ciclo Di Buffalmacco Nel Camposanto Di Pisa e La Committenza Domenicana),” Annali Della Scuola Normale Superiore Di Pisa. Classe Di Lettere e Filosofia 18, no. 4 (1988): 1557–1643; Malquori, “Luoghi e immagini nelle storie degli anacoreti di Pisa.” |

| ↑13 | My reading of the fresco at Santa Marta focuses primarily on the main horizontal plane of the pictorial landscape, looking at the narrative constructed there, but it also engages vignettes above and below that plane when they contribute to the narrative on the main plane. |

| ↑14 | Alessandra Malquori, Il Giardino Dell’anima: Ascesi e Propaganda Nelle Tebaidi Fiorentine Del Quattrocento (Florence: Centro Di, 2012), 90. |

| ↑15 | Lina Bolzoni, The Web of Images: Vernacular Preaching from Its Origins to Saint Bernardino da Siena (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2004), 1–40. |

| ↑16 | Corsi, Gli affreschi medievali in Santa Marta a Siena: studio iconografico, 10–11. |

| ↑17 | For a transcription of this document, see Aude Cirier, “Note sur le monastère de Santa Marta in Siena: la revision d’une foundation attribuèe à Milla des Comtes d’Elci (1328–1329),” Bulletino senese di storia patria 109 (2002): 497–531. |

| ↑18 | Archivio di Stato di Siena, Diplomatico Santa Marta, 1328 febbraio 6. Also see, Corsi, Gli affreschi medievali in Santa Marta a Siena: studio iconografico, 7–10. |

| ↑19 | Corsi, 22–4. |

| ↑20 | Corsi, Gli affreschi medievali in Santa Marta a Siena: studio iconografico, 78–80. |

| ↑21 | Corsi, 77–78. |

| ↑22 | This might account for some of the vignettes in the Thebaid at Santa Marta that are not usually included in frescoes of the genre. For information on the vignettes and their source material, see Corsi, Gli affreschi medievali in Santa Marta a Siena: studio iconografico, 81-111. |

| ↑23 | Corsi, Gli affreschi medievali in Santa Marta a Siena: studio iconografico, 55. |

| ↑24 | Also known as the Vitas Patrum in Antiquity. For the history of the late antique tradition of the Vitae Patrum, also known as the Vitas patrum, see Eva Schulz-Flügel, “Zur Entstehung der Corpora Vitae Patrum,” in Papers Presented to the International Conference on Patristic Studies, ed. Elizabeth A. Livingstone (Leuven: Peeters, 1989), 289–300. The literature on the Vitae patrum is too extensive to cite here. For an overview, see Eva Schulz-Flügel, “Zur Entstehung der Corpora Vitae patrum,” in Studia patristica 20: Papers Presented to the Tenth International Conference on Patristic Studies Held in Oxford, 1987, vol. 2: Critica, Classica, Orientalia, Ascetica, Liturgica, ed. Elizabeth A. Livingstone (Leuven: Peeters, 1989), 289–300. |

| ↑25 | Although there is debate over whether the document was actually written by Pope Gelasius, in the document still known as the Gelasian decretal of 494, the writer recommends the “Vitas Patrum, Pauli, Antonii, Hilarionis et omnium eremitarum quas tamen vir beatus scripsit Hieronymus cum omne honore suscipimus.” Decretum Gelasianum IV, 4, 220. Quoted in Duncan Robertson, The Medieval Saints’ Lives: Spiritual Renewal and Old French Literature (Lexington, KY: French Forum, 1995), 77. Schulz, “Zur Entstehung der Corpora Vitae Patrum,” 291. |

| ↑26 | This might account for some of the vignettes in the Thebaid at Santa Marta that are not usually included in frescoes of the genre. For information on the vignettes and their source material, see Corsi, Gli affreschi medievali in Santa Marta a Siena: studio iconografico, 81-111. |

| ↑27 | “Benedicti Regula,” in Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum, ed. Rudolph Hanslik, vol. 75 (Vienna: Holder-Pichler, 1960), 202–204. |

| ↑28 | ‘Cest liuere <est> deviseie a la priorie de Kampseie de lire a mengier.’ f. 265v (British Library, Additional MS 7053). On this manuscript see Sandra Lowerre, The Cross-Dressing Females Saints in Wynkyn de Worde’s 1495 Edition of the Vitas Patrum: a study and edition of the lives of saints Pelage, Maryne, Eufrosyne, Eugene, and Mary of Egypt (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang: New York, 2006), lxii; David N. Bell, What Nuns Read: Books and Libraries in Medieval English Nunneries (Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 1995), 50, fn. 30. On reading the Vitae patrum during meal times see Mary CA. Erler, Women, Reading, and Piety in Late Medieval England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 126. |

| ↑29 | Elliott, Roads to Paradise: Reading the Lives of the Early Saints. |

| ↑30 | Patrologiae cursus completus: Series Latina, ed. J. P. Migne (Paris: Garnier, 1844–64), 73: col. 225 (hereafter, Migne, PL). |

| ↑31 | Elliott, Roads to Paradise: Reading the Lives of the Early Saints, 59, 83–85. |

| ↑32 | For a historiographical discussion on the issues of narratology and static images, see Suzanne Lewis, “Narrative,” in A Companion to Medieval Art: Romanesque an Gothic in Northern Europe, ed. Conrad Rudolph (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2006), 86–102. Also see Cynthia Hahn, Portrayed on the Heart: Narrative Effect in Pictorial Lives of Saints from the Tenth through the Thirteenth Century (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2001), 45–56. |

| ↑33 | Otto Pächt, The Rise of Pictorial Narrative in Twelfth-Century England. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1962), 1. |

| ↑34 | Lewis, “Narrative,” 88. |

| ↑35 | Mary W. Helms, “Sacred Landscape and the Early Medieval European Cloister. Unity, Paradise, and the Cosmic Mountain,” Anthropos 97, no. 2 (2002): 435–53. On the cloister and its liturgical function also see, Ángela Mata, “El claustro de la catedral de León: su significación en el contexto litúrgico y devocional,” in Congreso Internacional “La catedral de León en la edad media”: Actas León, 7-11 de Abril de 2003, ed. Joaquín Yarza Luaces, María Victoria Herráez Ortega, and Gerardo Boto Varela (León: Universidad de León, 2004), 263–95; Peter Klein, Der Mittelalterliche Kreuzgang. Architektur, Funktion und Programm (Regensburg: Schnell & Steiner, 2004); Elizabeth Hartog, “Architecture, Liturgy and Daily Life in the Abbey Church of Rolduc and Its Cloister,” in Kirche und Kloster, Architektur und Liturgie im Mittelalter. Festschrift für Clemens Kosch zum 65, ed. Klaus Gereon Beuckers and Elizabeth Hartog (Regensburg: Schnell & Steiner, 2012), 79–95; Valentina Gili Borghet, “Il chiostro nelle consuetudini dell’abbazia di San Benigno di Fruttuaria: Ipotesi di restituzione alla luce della liturgia processionale,” in Romanico Piemontese: Europa Romanica. Architetture, circolazione di uomini e idee, paesaggi, ed. Saverio Lomartire (Livorno: Debatte, 2016), 143–51. |

| ↑36 | Helms, 440. |

| ↑37 | Malquori, Il giardino dell anima, 90. Looking to the Thebaid at the Camposanto, Lina Bolzoni has argued similarly, noting, “The eye looking at the frescoes must be fed by memory of the preacher’s words. As we shall see, the interplay between words and images functions in such a way to guide reception, to force interpretation into one single channel.” Bolzoni, Web of Images, 20. |

| ↑38 | Malquori, Il giardino dell anima, 90. |

| ↑39 | Mary J. Carruthers, The Craft of Thought: Meditation, Rhetoric, and the Making of Images, 400-1200, Cambridge Studies in Medieval Literature 34 (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 7–60, 237. |

| ↑40 | Corpus christianorum, series Latina, 38, 465–466. Also see Carruthers, 355. |

| ↑41 | Carruthers, 252. |

| ↑42 | Carruthers, 253. |

| ↑43 | Carruthers, The Craft of Thought, 77–81, 253–254. |

| ↑44 | Carruthers, the Craft of Thought, 253–254. |

| ↑45 | Carruthers, The Craft of Thought, 254. |

| ↑46 | Carruthers, The Craft of Thought, 254. |

| ↑47 | Paul Crossley, “Ductus and Memoria: Chartres Cathedral and the Workings of Rhetoric,” in Rhetoric Beyond Words: Delight and Persuasion in the Arts of the Middle Ages, ed. Mary J. Carruthers (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 215. |

| ↑48 | See Beth Williamson, Reliquary Tabernacles in Fourteenth-Century Italy: Image, Relic, and Material Culture, Boydell Studies in Medieval Art and Architecture (Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, 2020); Emma Dillon, “Seen and Not Heard: Symbolic Uses of Notation in the Early Ars Nova,” Il Saggiatore Musicale 23, no. 1 (2016): 5–27. |

| ↑49 | The narrative from which this image derives isn’t clear. Maria Corsi is unconvinced that the image refers to the story of Giuliana, but the parallels suggest that there could be a possibility. Although one scholar has purposed that it derives from Domenico Cavlaca’s vulgarization of the Vitae patrum, Le vite dei santi padri, the details are not so similar as to confirm that it is the source. Corsi, Gli affreschi medievali in Santa Marta a Siena, 84. |

| ↑50 | On phantasms in general, see Mary J. Carruthers, The Craft of Thought: Meditation, Rhetoric, and the Making of Images, 400–1200, 132–33. On the Devil and his demons’ ability to plant demonic phantasms, see Walter Stephens, Demon Lovers: Witchcraft, Sex, and the Crisis of Belief (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002), 290–99 and 365–66; Stuart Clark, Vanities of the Eye: Vision in Early Modern European Culture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 123–60; Claudia Swan, “Counterfeit Chimeras: Early Modern Theories of the Imagination and the Work of Art,” in Vision and its Instruments: Art, Science, and Technology in Early Modern Europe, ed. Alina Payne (University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2015), 216–37. |

| ↑51 | See Jamie Kreiner’s discussion in Jamie Kreiner, Legions of Pigs in the Early Medieval West, Yale Agrarian Studies Series (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021), 161. https://doi.org/10.12987/yale/9780300246292.001.0001. |

| ↑52 | For examples see British Library MS. Add.54180, fol. 156 and BNF, MS. 870, fol. 147r. |

| ↑53 | Inbar Graiver, Asceticism of the Mind: Forms of Attention and Self-Transformation in Late Antique Monasticism, Studies and Texts 213 (Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 2018), 136. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781771103947. |

| ↑54 | PL 73: col. 762. |

| ↑55 | PL 73: col. 762. Also see Corsi, Gli affreschi medievali in Santa Marta a Siena: studio iconografico, 84–85. |

| ↑56 | Peter Brown, The Body and Society: Men, Women, and Sexual Renunciation in Early Christianity, Lectures on the History of Religions, New Ser. ; No. 13 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988), 228. |

| ↑57 | PL 73: col.137. “Idcirco necessarium est donum spirituum discernendorum a Domino petere ut possimus tam fraudes eorum quam studia pervidentes, adversus disparem pugnam unum Dominicae crucis elevare vexillum.” |

| ↑58 | PL 73: col.1014. See also Corsi, Gli affreschi medievali in Santa Marta a Siena: studio iconografico, 86–87. |

| ↑59 | For an overview of the spiritual senses in the Western Christian tradition, see The Spiritual Senses: Perceiving God in Western Christianity (Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University, 2011). |

| ↑60 | For an overview of Augustine’s understanding of the spiritual senses, see Matthew R. Lootens, “Augustine,” in The Spiritual Senses: Perceiving God in Western Christianity (Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University, 2011), 56–70. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139032797.006. See also St. Augustine, Works of Saint Augustine: Sermons (148-183) on the New Testament, ed. John E. Rotelle, trans. Edmund Hill, vol. 5 (New Rochelle, New York: New City Press, 1992), 122–123. |

| ↑61 | According to the Augustine Rule that they adopted as a community. On the Augustine Rule as adopted by female monastic orders, see Lisa Cremaschi, “Regola di Agostino,” in Regole Monastiche Femminili, ed. Lisa Cremaschi (Giulio Einaudi, 2003), 11–25. |

| ↑62 | PL 73: 359. Also see, Corsi, Gli affreschi medievali in Santa Marta a Siena: studio iconografico, 88–89. |

| ↑63 | PL 73: 359. |

| ↑64 | Matthew 19:21. |

| ↑65 | On spiritual mentorship in the Lives of the Desert Fathers, see Christine McCann, “Spiritual Mentoring in John Cassian’s Conferences,” The American Benedictine Review 48 (1997): 212–23. |

| ↑66 | Corsi, Gli affreschi medievali in Santa Marta a Siena: studio iconografico, 90–93. |

| ↑67 | In the Life of Paul of Thebes it is written that at the ripe age of 90, Anthony was made aware (in a dream) that there was someone in the desert far better than him and that he ought to go and visit. Carolinne White ed., ed., Early Christian Lives: Life of Antony by Athanasius, Life of Paul of Thebes by Jerome, Life of Hilarion by Jerome, Life of Malchus by Jerome, Life of Martin of Tours by Sulpicius Severus, Life of Benedict by Gregory the Great (London: Penguin Books, 1998), 78. |

| ↑68 | Corsi, Gli affreschi medievali in Santa Marta a Siena: studio iconografico, 7–14. |

| ↑69 | Cremaschi, “Regola di Agostino,” 16–17. |

| ↑70 | PL 23: col. 26. |

| ↑71 | PL 73: cols. 903–904; Corsi, Gli affreschi medievali in Santa Marta a Siena: studio iconografico, 96–97. |

| ↑72 | For an examples, see Pietro Lorenzetti’s Death of Judas in the basilica of San Francesco in Assisi, ca. 1316/17-19 and Giotto’s depiction of the Death of Judas in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, 1302-5. Janet Robson, “Judas and the Franciscans: Perfidy Pictured in Lorenzetti’s Passion Cycle at Assisi,” The Art Bulletin 86, no. 1 (2004): 31–57. https://doi.org/10.2307/3177399. |

| ↑73 | On images of suicide in the Middle Ages, see Benjamin Russell Zweig, “Depicting the Unforgivable Sin: Images of Suicide in Medieval Art” (Ph.D., Boston University, 2014). |

| ↑74 | PL 73 cols. 381–392. On images depicting the Life of Mary of Egypt see, Gallant, Illuminating the Vitae Patrum: The Lives of the Desert Saints in Fourteenth Century Italy, 89–113. |

| ↑75 | PL 73: col. 225. |

| ↑76 | PL 73: cols. 821–822. Also see, Corsi, Gli affreschi medievali in Santa Marta a Siena: studio iconografico, 101–2. |

| ↑77 | PL 73 cols. 225–232. On The Life of Macarius the Roman see , Gallant, Illuminating the Vitae patrum: The Lives of the Desert Saints in Fourteenth Century Italy, Chapter 4; Elliott, Roads to Paradise: Reading the Lives of the Early Saints, 8, 65–66, 110–115. |

| ↑78 | Gallant, Illuminating the Vitae patrum: The Lives of the Desert Saints in Fourteenth Century Italy, Chapter 4. |

| ↑79 | Frugoni mentions a hierarchical arrangement in her work. Frugoni, “Altri Luoghi, Cercando Il Paradiso (Il Ciclo Di Buffalmacco Nel Camposanto Di Pisa e La Committenza Domenicana),” 1585–1586. |

| ↑80 | St. Augustine, Works of Saint Augustine: Sermons (148-183) on the New Testament, 245. |