Dustin Aaron • Rhode Island School of Design

Recommended citation: Dustin Aaron, “Hermits, Holy Sepulchers, and the Limits of Wilderness at the Externsteine,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 12 (2025). https://doi.org/10.61302/ASUX6178.

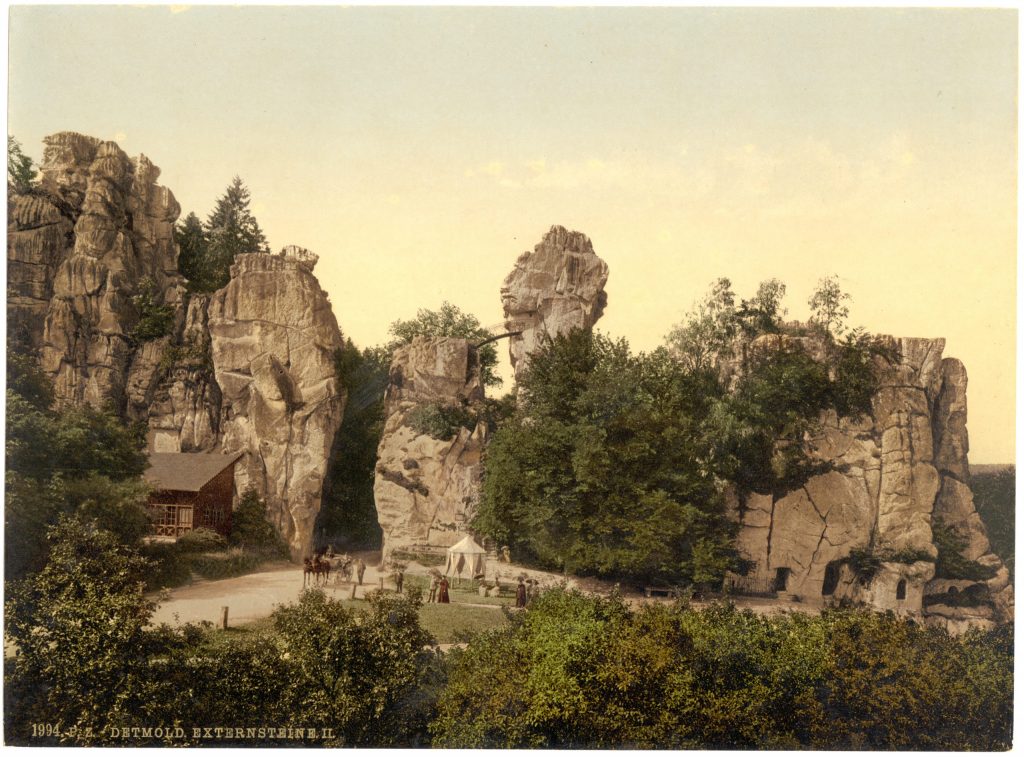

Fig. 1. The Externsteine, viewed from the northeast across the artificial lake. Photo: author (2024).

In a clearing deep within Germany’s legendary Teutoburg Forest, an imposing cluster of towering rocks rise like giant fingers thrust from the earth (Fig. 1).[1] These thirteen so-called Externsteine are naturally formed sandstone pillars, shaped by millennia of wind and rain to tower over the surrounding landscape. In more recent geological time, human interventions have also shaped the site. Carvers in the twelfth century expanded and connected two caves along the base of the westernmost and widest rock and added a chamber at the peak of the spindly second structure, reached by a stairway cut into the third. The most conspicuous of their interventions, seen clearly when approaching from the northeast, is a nearly six-meter-tall relief carving of Christ’s Deposition, or descent from the cross, surmounting a suffering Adam and Eve and crowned with the figure of the risen God (Fig. 2). In conjunction with a sarcophagus niche carved into a boulder at the same rock’s northern edge, the entire ensemble inescapably evokes the events and spaces of Christ’s death and resurrection, alluding through them to Jerusalem’s Holy Sepulcher complex. The caves and carving have long been assumed to participate in the popular medieval European tradition of ritually restaging Christianity’s holiest places, but the extent to which they were intended to do so from their inception is debated.[2] The modern willingness to see the Externsteine through this Holy Sepulcher lens changes based on how one understands the loose symbolic references to Jerusalem and the nature of the setting.[3] To many art and architectural historians, the supposedly remote forest appears frustratingly incongruous with the urban ambitions of a monumental sculpture and the public rituals that surround recreated holy sites—a paradox captured by Willibald Sauerländer’s description of the rocks as Golgotha in a “wild mountain forest.”[4] The inability to reconcile a very public function with a wilderness setting has, since the end of the Middle Ages, exposed the stones to counterfactual narratives, making it difficult, if not impossible, to say what the Externsteine once were and what they are now.

Fig. 2. Relief carving of the Deposition, flanked by entrances to the main cave in Rock I, with Saint Peter beside the left entrance. Photo: author (2024).

Attempts to tease out this incongruity in the history of the Externsteine remain vexed by noxious nationalist narratives and nature-cult fantasies. This imposition stems from nineteenth-century Romantic and identitarian movements that sought more profound meaning in the unusual landscape. For the ethno-nationalist German Völkisch movement, as later for the National Socialists, the Teutoburg Forest was the ultimate site of Germanic resistance to Ancient Rome and therefore the core site of national authenticity.[5] The only substantial archeology done on the Externsteine to date was carried out by völkisch nationalists looking to support the transformation of the stones into a Germanic cult site, supposedly recreating a pagan “wild sanctuary” of imagined pre-Christian worship.[6] A reluctance by professional scholars to return to such a politically loaded subject after the War opened the door to new-age mystical and racialized pseudo-scientific interpretations of the rocks, whitewashed of their völkisch—that is, ideologically populist—origins. Today, the Externsteine continue to be celebrated as a locus of transhistorical Germanic sun worship and communion with nature. In these narratives, the carved Deposition represents, at most, a foreign intrusion of Christianity, but it is just as often ignored so as not to conflict with the stones’ purported pagan identity. While renewed efforts by historians, archeologists, and art historians, have sought to counter the racial, and even conspiratorial thinking embedded in the wild sanctuary myths, there lies in those myths a kernel of truth. The many post-medieval reinventions of the stones were initiated by one of the few definitive facts surrounding the site: Externsteine was at times occupied by hermits.

By the fourteenth century, sources speak of a reclusorium at the Externsteine.[7] Implied in this Latin term for a hermitage is a sense of a place as closed off from the bustle of everyday existence, “somewhere wild and remote,” suitable for monks and especially recluses, who wished to emulate the archetypal isolation of the Desert Fathers.[8] Even as the nature of eremitic life shifted in the eleventh and twelfth centuries to become a more communal activity, eremitic identity throughout the Middle Ages rested on this ideal of desert solitude and theoretically was a primary factor in choosing locations for monasteries and hermits’ cells.[9] For over half a century now, historians have been unmasking ecclesiastic and monastic legends of solitude as artificial claims of naturalness and wildness, but there has been far less critical reevaluation of hermitages.[10] It is for this reason that even professional historians, archeologists, and art historians, who explicitly deny a pagan prehistory for the Externsteine, struggle against the logical impasse of how a quintessentially remote eremitic site can have a massive carved face like a billboard announcing a very public function.

Overcoming this impasse—reconciling the sculpture with the caves and supposedly remote setting—begins by asking how and for whom the Externsteine and their imagery worked. But to best demonstrate what is at stake in untangling this eremitic knot, in what follows I will work backwards, starting with contemporary neo-pagan celebrations, and passing through the National Socialists, nineteenth-century Romantics, and early modern Humanists.[11] This ultimately leads to the medieval Externsteine, which appear to have uncontroversially balanced the paradox of being both a popular and highly accessible cult site and a hermitage. By working through the reception history of the monument, through an inflection point in the sixteenth century, and to the twelfth-century origins of its main figural sculpture, a case emerges in which an ascetic tradition gives rise to its wilderness setting (not the other way around). While the realization that wilderness is a product of human invention, rather than the absence of it, has long been a staple of eco-critical scholarship, this recognition is especially poignant in the religious landscape of medieval Europe, built as it is on the fiction of late-antique eremitism and monastic isolation.[12] Recognizing this history at Externsteine might thus begin to peel back the insistent romanticism surrounding other sites of medieval eremitic wilderness; a romanticism that has opened similar landscapes to fetishization, whether from the medieval imagination, modern fascism, or postmodern neopagan environmentalism.

The Externsteine Today

As the sun began to set on the 2024 summer solstice, small groups of revelers carrying tents and towing wagons loaded with sleeping bags and firewood slowly emerged from the surrounding tree line to gather on the fresh mowed lawn before the Externsteine. This remarkably heterogenous crowd included bare-footed and dread-locked teenagers in drum circles, young families in recreated medieval costume (some with fantasy-inspired elf ears), and pensioners cheerily distributing bottles of beer from their camping chairs. All had come to witness the next morning’s rising sun and celebrate a centuries-old celestial communion with nature channeled by the soaring rocks.

Fig. 3. Tourists view the remains of the upper chamber at the top of Rock II. Photo: author (2024).

The kind of esotericism on display at the Externsteine, linking ecological and anti-capitalist politics with a non-specific spirituality, has had a steady presence in mainstream German culture since the 1960s. It is often infused with adaptations of East and South Asian practices—seen through an Orientalizing lens as admirably esoteric—as one group demonstrated by constructing their campsite from cloth hangings printed with Buddhist mandalas. In some cases, the priority remained political, even anti-war, as was emphasized by two young women who carried signs directed at the ongoing conflict in Ukraine. What all parties had in common was a belief in the Externsteine as a place of power. When asked, most suggested that the rocks in some way mediated between the earth and heavens.[13] This could be proven, they believed, by the upper chamber, now without a roof, carved into the second rock (Fig. 3). The east side of the chamber is shaped into a rounded niche, within which sits a small stone altar. On the wall above the altar is an oculus that anticipates the direction of the rising sun. Supposedly in perfect alignment with the solstice dawn, the solstice watchers understood this feature to demonstrate the site’s long history as a locus for channeling the natural cycle of the earth.[14]

Fig. 4. Revelers at the Externsteine prepare for the solstice celebrations with inset detail. Photo: author (2024).

Bound at least outwardly in the comradery of new age spiritualism, the celebration was theoretically washed of any hints of ethno-nationalism that have long been a feature of neopagan celebrations in Germany.[15] One participant in Viking-inspired garb, however, had shaved around his head to better display normally hidden tattoos (Fig. 4). On the back of his head, rising on a stepped pyramid, sat a representation of the forked tree that Nicodemus stands upon in the Externsteine Deposition. In the tattoo it had been returned upright from its bent position in the sculpture, a reference to a century-old nationalist belief about the Deposition image. Since at least 1928, the tree has been believed in neopagan circles to represent Irminsul, the sacred tree of the Saxons, which was bent in the sculpture as a propagandistic nod to the victory of Charlemagne and domination of Christianity in the eighth century.[16] The “righted tree” then emblematizes a return to native German roots. To the right of the tree is the figure of a man holding aloft a sword. This is undoubtedly a rendering of the nineteenth-century Hermannsdenkmal, or the monument to Hermann (Arminius) the Germanic chieftain who defied Rome, erected just over the hill from Externsteine (Fig. 5). These symbols were in turn flanked by a runic alphabet that ran in a line from behind his left to his right ear. The composition thus forms a comprehensive narrative, uniting strains of popular belief that link prehistoric pyramids to Germanic nature-cults and militaristic nationalism. While the political sympathies of the tattooed man can only be guessed, similar runes can also be spotted scratched onto inconspicuous parts of the Externsteine. These include the othala (ᛟ), favored by the European far right, but also swastikas, betraying without question the ideological bent of some visitors. The Externsteine are thus the focal point of a contemporary völkisch ideology built around an idea of timeless racial continuity, bound with a national resurrection myth that seeks a return to a pre-Christian German identity.[17]

Fig. 5. The Hermannsdenkmal, Detmold, designed by Ernst von Bandel, constructed 1838–1875. Photo: author (2024).

Much of the mythologizing assembled in the man’s tattoos was codified by the local Forschungskreis Externsteine, a “research circle” founded by Walther Machalett (1901–1982), a former Nazi and pseudo-historian.[18] Machalett notably linked Externsteine to the Egyptian pyramids as sites of cosmic knowledge assembled by an ancient white Aryan priesthood.[19] He was himself building on some of the more nefarious myths of twentieth-century racial occultism, for example, the belief that the Aryan race originated from the lost city of Atlantis and that it would reemerge to overthrow a decadent modern age. While these ideas originated with nineteenth-century occultists like the Russian-American Helena Blavatsky and Austrian Guido von List, their political spiritualism passed smoothly into Nazi ideology and is not easily separated from it today.[20]

Machalett’s interpretations, however, are not the only ones to circulate both within the Forschungskreis and independent of it. The popularization of the Externsteine as a neopagan site is more thanks to the post-War efforts of Herman Wirth, through his Gesellschaft für europäische Urgemeinschaftskunde (Society for European Prehistory, today called Ur-Europa e.V.), and Ulrich von Motz’s publishing house Hohe Warte, through which Motz distributed pamphlets at the stones.[21] Both popularized esoteric ideas by shifting from an overtly racial to an ecological framework. Until the 1990s, Wirth’s student Werner Georg Haverbeck featured the stones in wellness seminars put on by his Collegium Humanum that softly embedded scientific racism into themes of organic farming and green spirituality.[22]

Their effect was such that even less obviously nationalistic organizations took for granted the Germanic cult history of the site. For example, the anthroposophists, followers of Austrian occultist Rudolf Steiner, quickly adopted the Externsteine as a spiritual beacon. While not a racist organization, anthroposophist writers tend to commit the basic logical fallacy of starting from a predetermined conclusion—that the stones are a Germanic cult site—and searching for or inventing evidence that incidentally reinscribes völkisch ideology.[23] The Externsteine form, in the words of Stefanie Haupt, the “lowest common denominator” for a multitude of conspiracy-minded parties, while simultaneously offering valid spiritual experiences to many well-meaning communities.[24]

Although the revelers were not united by a single politics or belief system, the range of pseudo-history that joins them in believing the Externsteine to be a Germanic cult site are all united around one crucial conviction. They perceive the stones to represent an indigenous German identity. As often happens, indigeneity is here collapsed into an idea of nature, with attendant associations of purity and primitivism.[25] The recent ecofiction novel Tanfana, carried at the solstice celebration by at least one young participant, poses the historical Germanic worshippers at the Externsteine as “close to nature,” struggling to defend their spiritual culture against the evil materialistic Romans.[26] Many of the revelers sought to emulate this posture. They were there to experience nature directly, stripped of any modern technological or “foreign” cultural mediation. Whether explicitly ethno-nationalist or focused on personal spirituality, the people gathered to observe the solstice sun were in thrall to the supposed naturalness of the site. Lest it spoil this effect, a patch of trees keeps the well-appointed visitor center and restaurant carefully hidden from view.

Under National Socialism

In 1965, North Rhine-Westphalia state archivist Erich Kittel tried to dispel the völkisch ideologies that clung to the stones after the War, publishing the first clear rebuttal to popular pseudo-histories of the Externsteine.[27] Per Kittel, it was the Nazis who mainstreamed the racialized interpretations of the site before the War and whose legacy prevented any scholarly rejoinder in the two decades since. He traced this to a pivotal event under SS head Heinrich Himmler’s stewardship of the Externsteine. In June, 1935 the National Socialists held the first notable solstice celebration at the rocks.

It is unsurprising that the Externsteine attracted the attention of Himmler and his SS Ahnenerbe, the body responsible for the research of “ancestral heritage” under the Nazi party structure. The Ahnenerbe were fascinated by Tacitus, with his description of Arminius’ victory in the Teutoburg Forest. The Nazis sought the “savage altars” described by the Roman historian as lying in the woods near the battlefield.[28] But even before Himmler and Wirth formed the Ahnenerbe, local nationalist organizations, like the Reichsbund für Deutsche Vorgeschichte (Imperial Association for German Prehistory) were already eyeing the Externsteine. A year earlier, völkisch lay archeologist Wilhelm Teudt, promoter of the Externsteine tree as Irminsul, prompted the local government to begin archeological excavations at the foot of the rocks to prove that these were said altars.[29] Although they never produced evidence of anything older than the Middle Ages, the Externsteine, as an imagined pre-Christian cult site, nevertheless became so important to Nazi ideology that by 1936 Teudt’s upright tree became one of the Ahnenerbe’s first emblems.

The Ahnenerbe worked in the circular logic already described above. From the predetermined conclusion that the stones were once a wild Germanic cult site they sought or invented proof that this was the “savage altar” of Germanic tree worship, later felled by Charlemagne.[30] Crucial to their “proof” was the setting. A wild sanctuary with a cult tree must have been deeply forested. The later presence of Christian hermits reinforced their belief that a dense forest once surrounded the stones, and that the forest must have faded to desecration and development after the site was abandoned in the early modern period. The first step in returning the stones to their Germanic glory, then, was replanting the forest. For this, the SS turned to Teudt. Teudt planned to restore the Externsteine to their “original” state and to drain the pond that had been added in 1836.[31] The road, Reichsstraße 1, which ran through the middle of the Externsteine on its way from Aachen to Königsberg (Kaliningrad), had to be relocated, while a children’s rehabilitation center and a hotel built in front of the stones were torn down. These supposedly anachronistic additions to the site would be replaced by a “sacred grove” of “unspoiled natural beauty” and a meadow—the same meadow used by the thousands of summer solstice participants who continue to worship its natural beauty to this day.[32]

Nationalism and the Nineteenth Century

The demolition of buildings and roads might imply that the Externsteine were highly “unnatural” before Teudt’s interventions. He was, however, largely undoing attempts by nineteenth-century romantics, who themselves sought to bring the stones into closer alignment with their views of an ideal nature. In 1810, the Princess Pauline of Lippe ordered the ruins of an elaborate Baroque folly be removed from the Externsteine in order to restore the rocks’ natural attraction.[33] No less a figure than Goethe was inspired by the new popularity that followed this renovation. He was tempted to the rocks by a cast and drawing of the Deposition circulated by Prussian court artist Christian Daniel Rauch in 1824. In a short article circulated in his journal Über Kunst und Altertum, Goethe speculated on the stones’ pagan cult history and affirmed their identity as “hermitages and chapels” (Einsiedeleien und Capellen).[34] Significantly, he popularized the story of Carolingian conversion. For Goethe, the carved Deposition was meant to educate and “empower the imagination” (Einbildungskraft) of the newly converted faithful after Charlemagne’s conquest.[35]

Over the next decades, the renewed Externsteine began to take on an explicitly nationalist identity in line with developments across the German world, bringing further attention to the site. From its inception in 1838, the stones were linked with the Hermannsdenkmal, the colossal copper sculpture of Arminius, built on what was at the time believed to be the site of the legendary battle (see Fig. 5). Only completed in 1875, after Lippe joined the new German Empire, the enlarged political context and the monument’s nationalistic appeal to a fervent pan-Germanism drew in unprecedented visitors to both sites. To accommodate this influx, the State of Lippe expanded the highway running through the rocks and eventually added an early tram to carry tourists from nearby Horn. Inns and other attractions emerged as well around the recently dammed pond.

Fig. 6. Postcard of the Externsteine, c. 1890–1900, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LOT 13411, no. 0655. Published under fair use.

The late nineteenth-century Völkisch movement that brought this renewed attention to the Externsteine was largely a response to industrial upheaval and land reforms.[36] Adherents to the various “blood and soil” ideologies spoke of a disillusionment, a distancing from the land, and a lack of cultural anchoring combined with “racial decline.”[37] They therefore advocated for cultural and social reforms meant to restore the human relationship with nature and “purge” German society of foreign elements, including, in some circles, Christianity. It is in this heyday of völkisch exuberance that the Deposition most receded from view, in some cases literally hidden as in a popular turn-of-the-century postcard (Fig. 6). Völkisch efforts were most concentrated in the north, around the Harz Mountains and Teutoburg Forest, stylized as the most Germanic spaces in the Empire. The myth of Arminius therefore took pride of place in their romanticized rebirth of a noble and homogeneous Ancient Germania—all that was needed was to locate the wilderness of his pagan shrine.

Reformation

As great a storyteller as he was, Goethe did not invent the tale of Carolingian conversion projected onto the carved Deposition. He must have known, or spoken to someone who knew, the 1564 report of local priest, Hermann Hamelmann. Hamelmann was possibly the first to connect in writing the Externsteine with the pagan shrine destroyed by Charlemagne in 772.[38] His report also noted that upon the erection of Charlemagne’s altar, sculptors were employed to adorn the new shrine with portraits of the apostles. Though a large sculpture of Saint Peter today stands guard by the left entrance of the main cave, behind the carved Deposition (Fig. 7), and the base of another robed figure similarly holding a banderole lies toppled between the first and second rocks (Fig. 8), it is difficult to know whether Hamelmann based his report on now-lost carvings he observed at the stones or if he projected onto them a textual history describing Charlemagne’s conquest. In either case, connecting the carvings to Charlemagne led him, and Goethe in turn, to declare the Externsteine Deposition the oldest Christian sculpture in Germany.

Fig. 7. Relief of St. Peter to the left of the main cave entrance. Photo: author (2024).

Fig. 8. Fragment from the base of a carved figure in robes holding a banderole, possibly an Apostle. Photo: author (2024).

Around the time Hamelmann was writing, an even more consequential text was appended into a fourteenth-century collection in the monastery of Werden. Therein, an anonymous hand recounted “a large rock between the city of Paderborn and the town of Horn. In this rock is hewn a chapel commonly called Exsterensteyn. Recluses, or hermits, inhabited this place until our times, when, having been caught as robbers, they were expelled and uprooted.”[39] The Werden note introduces the heart of a story that would come to dominate the public image of the Externsteine in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries—one of unhinged hermits who robbed and murdered travelers passing through the surrounding woods. Whatever truth lay behind the stories, the vicious characterization of “evil” hermits occupying a “temple of murder,” was a characteristically Reformation jab at a traditional Catholic practice of eremitism, amplified by outspoken Protestant priest Johannes Piderit (1559–1639). Piderit recounted a version of the tale in his Chronicon comitatus Lippiae, in which the devil, unable to simply knock down the stones, persuades the hermits to commit fornication, robbery, and murder, ultimately leading the local authorities to expel the men and tear down their hermitage.[40] Rather than a pagan past, Piderit imagines the Externsteine to be the result of a Christian golden age in which the “ancients” built a hermitage on this miraculous site “out of good devotion and faith,” but which was tainted by the misdirection of the Catholic church.[41]

It is to Hamelmann and Piderit that we owe the storied identity of the Externsteine which passed, through Goethe and others, into modernity. Piderit solidified knowledge of a long history of Christian eremitism that ended ignominiously while Hamelmann invented, or at least popularized, the idea that this Christian eremitism was built on a non-Christian Germanic site. Hamelmann’s description of the sculpture made it inseparable from a missionary goal and tied to German paganism, while Piderit ignored it entirely. Both legends revolved around a romantic wilderness of religious devotion, and both saw the hermits abandon the site by the early sixteenth century. The second half of the sixteenth century is thus an inflection point. Any genuine medieval history of the stones was overwritten by a double narrative of eremitism and Germanic worship, setting the tone for future descriptions of the Externsteine as a wilderness rife for ideological exploitation.

There is no evidence among surviving legal records of charges against the hermits at the Externsteine or anything that would explain their eviction beyond the usual consequences for being a Catholic cult site in Reformation Lippe.[42] It is therefore hard to believe that the hermits left their charge to ruin and preyed upon vulnerable travelers in the woods. But the opportunity for exploitation primed by Hamelmann and Piderit did not take long. By 1659, Count Hermann Adolphus of Lippe developed the former hermitage at the Externsteine into a sovereign Lust, an excursion and amusement site popular in the Baroque period.[43] Building his grand architectural folly around the stones involved carting away the Catholic accoutrements that remained in the caves, and disassembling a chapel dedicated to the Holy Cross. The hunting lodge and decorative fortifications added by Count Hermann Adolphus, however, fell into disrepair shortly after his death, leaving the Externsteine looking very much like a disastrous ruin abandoned by bad hermits until Princess Pauline’s intervention 150 years later. As each generation relied on the characterizations and transformations of the previous, they added to the house of cards upon which our perceptions of the Externsteine sit. Stepping backwards through the post-medieval history of the stones shows how the recorded presence of hermits in the late Middle Ages, was filtered through Reformation propaganda and escalated over centuries of shifting cultural expectations to transform a medieval wayside chapel into a Germanic shrine, temporarily converted by evil Catholics, built for channeling the passage of the sun in communion with nature.

The Medieval Externsteine

The myth of the Externsteine as a pre-Christian Germanic cult site can be put aside, at least for now. As shown above, the legend began in the sixteenth century with the priest Hamelmann and neither investigative digs in the late nineteenth century nor the full archeological campaign in 1934 uncovered evidence of human presence at the stones before the turn of the last millennium.[44] There are still many unresolvable questions lingering around the Externsteine, but perhaps the most pertinent to this special issue is when they became a hermitage. Local historian Roland Linde has suggested that the stones were unlikely to have contained a hermitage long before the mention of a domus recluse in 1366.[45] He argues instead that the high medieval additions of a carved arcosolium with a human-shaped tomb (Fig. 9) and the Deposition relief predestined the site to become a hermitage once eremitism reached its height of popularity in the fourteenth century. The closest comparanda for rock-cut hermitages, like Bretzenheim in Rhineland-Palatinate or the rock-cut catacombs behind St. Peter’s in Salzburg, are much older, but it is similarly unclear when those sites became genuine hermitages as opposed to remote chapels operated by regular clergy. Linde’s logic is almost certainly correct—that there is a link between the stones’ references to the Holy Land and their function as a hermitage—but, as I will argue in the remainder of this article, the two features are more closely intertwined than has previously been supposed. Highlighting their interdependency chips away at some of the mythology buttressing eremitic landscapes in the Middle Ages and today.

Fig. 9. Carved arcosolium with empty body-shaped sarcophagus niche, northern edge of Rock I. Photo: author (2024).

Determining the sequence, and thus relationship, of the medieval interventions at the Externsteine is no easy feat. The earliest and most secure date surrounding the stones is given in an inscription carved into the wall of the lower chamber. The inscription commemorates the consecration of an altar by Bishop Henry II of Paderborn (1084–1127) in either 1115 or 1119.[46] It is partly thanks to Henry’s consecration that the stones were long thought to belong to the Paderborn monastery of Abdinghof. This belief was for centuries corroborated by a recorded sale of the site to the monastery in the year 1093. Now known to be fictitious, probably from c.1300 (the original is lost), the so-called Kaufbrief (purchase letter) was more likely a deliberate forgery produced during a later dispute over the property between Abdinghof and the Lords of Lippe.[47] Instead, it is another recorded privilege, the so-called Meierbrief (steward letter) from the Abbot Bernhard of Werden in 1129, that offers better insight. Bernhard describes a stopping point at Egesterenstein, roughly halfway between the monastery in Werden and the monks’ property in Helmstedt, that was to be given to a certain Henry, a ministerial of Paderborn, who would be the villicus, or farm steward, tending the property for the abbots in their absence and hosting them twice annually on their journey to and from Helmstedt.[48] Henry was to be caretaker of the property, a job that might otherwise be assigned to a hermit. But this does not exclude the possibility that in addition to Henry there was also a hermit at the stones. Franz Flaskamp, who first noted the proof of Werden ownership, speculated that the steward would have been sufficiently occupied with paying his tenancy and servicing the monks and abbot on their overnight stays between Helmstedt and Werden, something corroborated by a c.1150 letter from Abbot Wilhelm which notes the annual dues for the villicus on their territorium in Holthuson sive Eggesterenstein.[49] The 1129 letter accounts for instances when a monk or canon would attend to the altar at the Externsteine, but, as Flaskamp notes, it was also necessary to maintain the cult site on the rocks between the occasional days when clergy would come to celebrate Holy Week, the Invention (May 3), and the Exaltation of the Cross (September 14).[50] This therefore leaves the possibility of a hermit or hermits being stationed at the Externsteine from 1115, in addition to the secular caretaker appointed in 1129.

We are on somewhat more solid ground thanks to recent scientific testing. Stimulated luminescence dating of stone drilled from the ceilings of the cave, carried out in 2004, determined that fire mining was used to expand the interior space in two distinct construction phases in the late eleventh or early twelfth century and in the late twelfth or early thirteenth.[51] The earlier phase likely expanded preexisting hollows in the rock to make a suitable chapel and concluded with the consecration of the altar by Bishop Henry II of Paderborn in 1115 (or 1119)—hence, the caves were fit for a hermit by this earliest date. The study’s authors also suggest that the arcosolium with the empty tomb was carved out at this same time, as part of a phase attributed to the abbots of Werden. They then ascribe the high chamber with its altar niche and the carved Deposition to the second phase of cave expansion—a phase they attribute to a change in ownership or a reimagining of the Externsteine around 1190.

While art historians long used the secure date of 1115/1119 to date the figural sculpture on the Externsteine, a link between the altar consecration and the Deposition scene is no longer assumed. Most recent arguments, as articulated by Roland Pieper, take into account the later second phase of human intervention in the caves and so link the sculptures to the documented takeover of the Externsteine by the lords of Lippe around 1190.[52] Roland Linde and Ulrich Meier have gone even further, arguing that the Deposition was commissioned by a specific Lippe lord, Bernhard II (d. 1224).[53] They see the sculpture as linked to Bernhard’s preaching for the Livonian Crusade in 1220, reflecting his special veneration of the Holy Cross and for the cult of the Virgin Mary. They also propose that the chapel within Rock I was dedicated to the Holy Cross by Bernhard as early as c.1200, around the same time he consecrated an altar dedicated to the Holy Cross in the Cistercian Abbey of Marienfeld, where he had retired. The veneration of the Virgin was undoubtedly crucial to Bernhard, as evident in his naming of Marienfeld and two churches dedicated to St. Mary in Lippstadt, but the later twelfth century was a period of fervent Marian devotion and there is nothing notable about the figure of Mary carved at Externsteine that might suggest a particular connection to Bernhard. The dedication to the Holy Cross perhaps more persuasively points to Bernhard, but there is no secure evidence that a chapel at the Externsteine was dedicated to the Holy Cross before 1429, which corresponds with other Holy Cross chapels in the surrounding area.[54] Following the few inscribed dates therefore still leaves a range of a century for dating the sculpture and little more insight into the presence of hermits.

The range is only somewhat narrowed by focusing on style or iconography. The usual searches for local stylistic comparanda have tended to link the Freckenhorst baptismal font, once also thought to be early twelfth century but now redated closer to 1200.[55] While the font similarly centers a crucified Christ, in this case set within an arcade wrapping the basin with other New Testament scenes, the treatment of hair, the disposition of the figures’ bodies, and the method of undercarving all suggest little relation with the Externsteine. Similar stylistic differences separate the Deposition from architectural sculpture in nearby Soest, Erwitte, and the tympanum of St. Mary’s in Lippstadt, which are commonly cited for how the reliefs emerge freely from the flat surface without framing or demarcation.[56] The lack of explicit deference to architectural framing might be more unusual on a church façade, but the Externsteine, crucially, are not built architecture. There are no pseudo-architectural details cut into the exterior of the rock, so there is little reason to expect the sculpture to relate or not relate to architectural norms in ways comparable to ashlar construction. While still far from the mark, the most striking stylistic similarity to the tapering geometric regularity of the bodies and draperies, like the loops coming off Christ’s loincloth or Joseph’s S-curved torso, as well as the head-to-body proportions, might surprisingly be the mid-eleventh-century carved wooden Madonna donated by Bishop Imad to Paderborn cathedral (Fig. 10), suggesting a strong stylistic conservatism or deference by the responsible artists.[57]

Fig. 10. Imad Madonna, Paderborn, Diocesan Museum SK1. Photo: © Genevra Kornbluth.

Fig. 11. Deposition fresco, 1164, Saint Panteleimon, Gorno Nerezi, North Macedonia. Photo: Byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

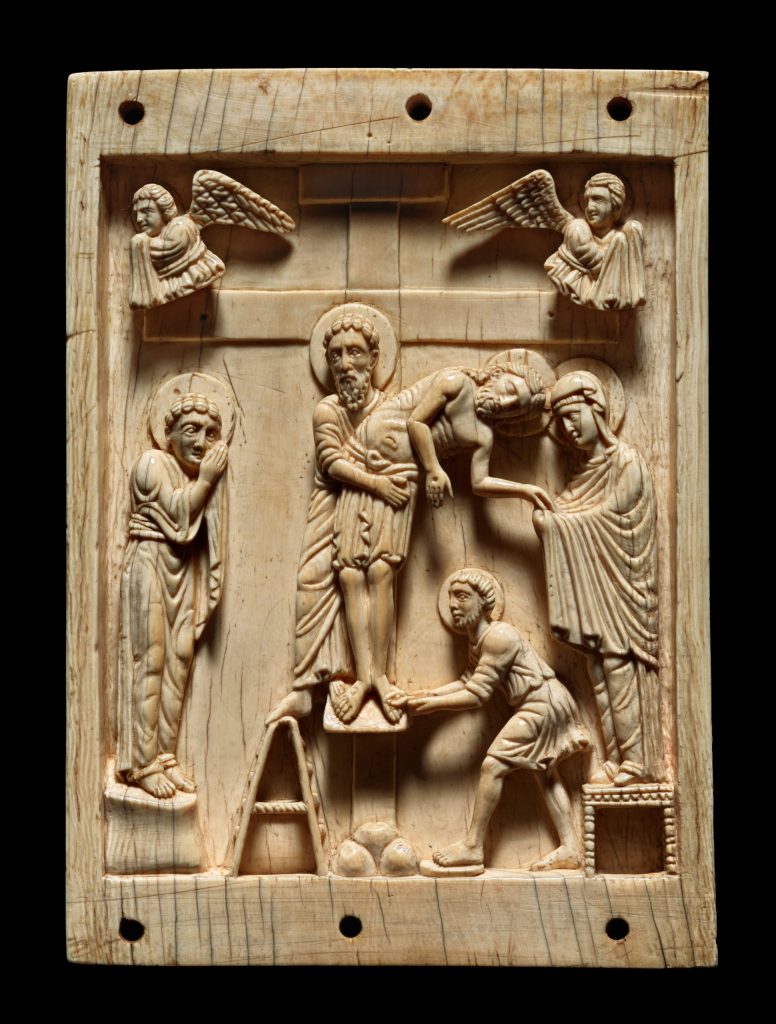

Fig. 12. Descent from the Cross, ivory, Italian c. 1180–1200, Boston, Museum of Fine Arts 34.1462. Photo: © 2025 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Without better monumental comparanda the default is to suggest lost portable works. Because depictions of the Deposition are so rare in Western Europe before the thirteenth century, some, like Johannes Mundhenk, have pointed towards Byzantine wall paintings, like those from Aquileia (c. 1180) and Nerezi (c. 1164) (Fig. 11) as prestige models that were carried to northwest Germany through now lost book paintings or ivory carvings.[58] These examples are arguably the closest comparisons iconographically, and most importantly they generate some of the same striking pathos through the utter limpness of Christ’s body. Byzantine (or Byzantinizing) ivories of the Deposition were indeed in circulation in the twelfth century, which can be seen through two nearly identical examples, one today in Boston (Fig. 12) and the other in Hildesheim, the latter of which is believed to have been copied in Venice before traveling to the German city.[59]

Though the Aquileia and Nerezi frescoes and the more portable ivories all suggest ways in which the Deposition iconography could have been popularized in twelfth-century Lippe, none of them sufficiently mirror key features of the Externsteine Deposition, including the face-down orientation of Christ’s body. The ninety-degree angle of his falling body, which mirrors the bent tree to his right, seems to instead anticipate the emotionally weighty Depositions of Gothic ivories and manuscripts from the middle of the thirteenth century. Similarly, the tree that Nicodemus surmounts to reach the Cross, rather than the usual steps or stool, might allude to the living wood of the Cross—an argument only made more compelling by recent research on the cult of the Tree of the Cross which began to grow in the later twelfth century.[60] On the contrary, the personified sun and moon hovering above the corners of the cross recall much older iconography of the Crucifixion.[61] The Adam and Eve in a clearly defined register below the Deposition are also uncommon and, like the personified celestial bodies, adopted from Crucifixion iconography. Without further comparanda, the Externsteine Deposition appears to be a very novel interpretation of a relatively uncommon Biblical scene, perhaps reliant on more portable artworks, but more so straddling a stylistic and iconographic conservatism and precociousness that would make for a memorable viewing experience whether closer to 1119 or 1220.

Fig. 13. Detail from the Externsteine Deposition of the risen Christ with a robed kneeling supplicant (head now missing) on his left arm. Photo: author (2024).

Fig. 14. Detail of the Risen Christ from the Crucifix of Ferdinand and Sancha, Madrid, National Archaeological Museum 52340. Photo: author (2024).

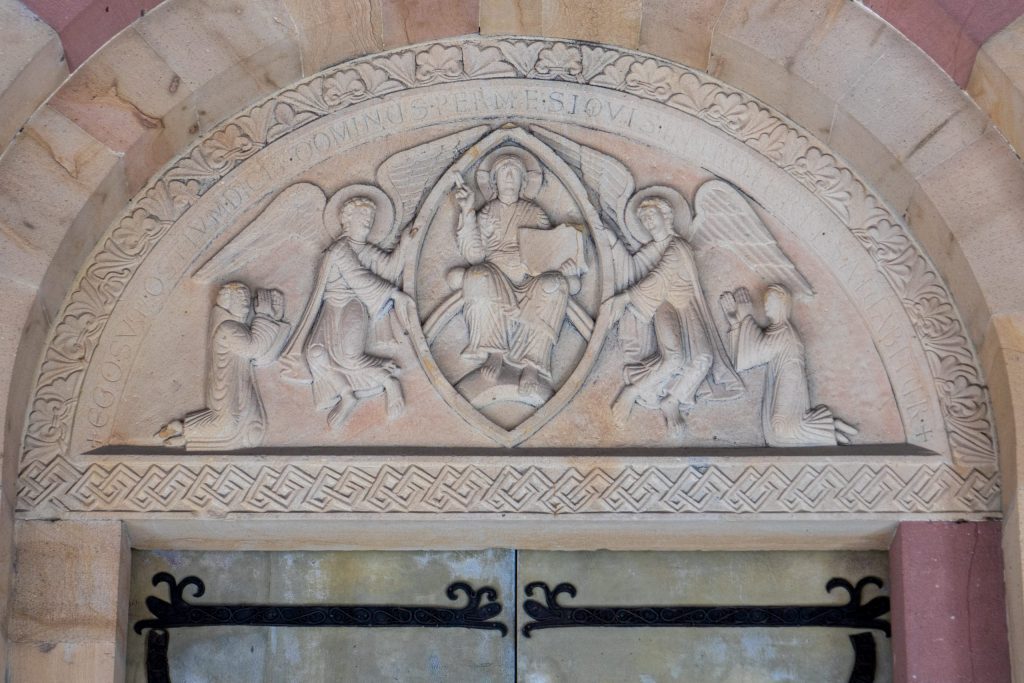

This precociousness, and a clue to dating the sculpture, is perhaps most apparent in the cross-nimbed man emerging from the left arm of the cross (Fig. 13). While Panofsky identified this “almost unique” figure as God the Father, this is far more likely the resurrected Christ, holding a cross staff similar to the resurrected Christ carved above the corpus on the mid-eleventh-century ivory crucifix of Ferdinand and Sancha (Fig. 14).[62] The towering God also holds a now-headless kneeling figure in the crook of his left arm. Depending on whether the larger figure is identified as the Father or the Son, the small figure has been interpreted respectively as the soul of the dead Christ or of a rescued Adam.[63] The kneeling figure is, however, clothed, which would be unusual for depictions of saved souls, which are normally nude or swaddled (and seldom carried by Christ, except for the Virgin at her Dormition). While little can be determined conclusively without the head, between the beseeching hand gesture and posture pointed towards the resurrected Christ, the figure far more closely resembles twelfth-century donor figures.[64] He is remarkably similar in posture and dress to male figures like the one kneeling in supplication before the Christ in Majesty on the tympanum of Alpirsbach Abbey (Fig. 15)—a figure Rainer Budde has described as wearing monastic robes.[65] While unusual, Christ’s bosom offers a compositionally and rhetorically sensible place to put a plea for a patron’s salvation, especially if that patron is already deceased. The lack of other attributes makes it impossible to more precisely identify the figure, but any of the abbots of Werden, Abdinghof, or bishops of Paderborn—all of whom in the twelfth century were also monks or cathedral canons—might posture the kind of mixed hubris and humility at play here.

Fig. 15. Tympanum of Christ in Majesty flanked by angels and kneeling figures, Alpirsbach Abbey, Germany. Photo: author (2022).

In this case, identifying the figure as a monk further supports associations with Bernhard II of Lippe. Bernhard took monastic vows after 1198, and so could be the one depicted in the sculpture. Such an identification would date the carving after 1198, though it does not necessarily mean it was executed after Bernhard’s death in 1224. While kneeling donors often fulfill a funerary function, there are sufficient examples from the twelfth century of living donors, especially clerics, inserting themselves into commissions in anticipation of their future memorialization.[66] Nevertheless, it should be acknowledged that this theoretical patronage would be in his capacity as a monk and therefore unusual for a Cistercian. In any case, this tentative identification of the kneeling figure with Bernhard further supports dating the monumental sculpture to a second campaign to remake the Externsteine, likely closer to 1200.

Fig. 16. Remains of Falkenburg castle, Teutoburg Forest, Germany. Photo: author (2024).

While this line of argumentation might ultimately support assigning the carved Deposition to Bernhard II’s initiative, it crucially undermines the logic upon which that attribution has to date rested. Lippe patronage has, until now, been based on an assumption voiced by Pieper: “Who else could have created such a relief here, in the seclusion of the Lippe woods?”[67] The question assumes it was restrictively difficult, and therefore expensive, to move materials and labor through this remote place. Only two years before his illness and monastic withdrawal, Bernhard called a team of builders to construct a castle, the Falkenburg, on a hill three kilometers deeper into the woods (Fig. 16), thus proving he had the resources to overcome such “wilderness.” This logic, however, falls into the same trap as modern distorted views of the Externsteine, the least of which is ignoring that the stones lie on a major road. The required labor is also not comparable. There is no known sculpture from the Falkenburg, and inversely the ashlar carvers from the castle would not be needed at the Externsteine, where the stone was, essentially, already in place. Most importantly, the Externsteine was not secluded. The Meierbrief from the abbots of Werden includes a note that if the abbot did not come for two or three years, the Meier was to stock his stores for future accommodations and take care of the buildings and other culturae of the abbot (edifficiis nostris et aliis culturis nostris).[68] Mundhenk has rightly pointed out that the culturae, in this case refer not to cultivated land but to other buildings, suggesting a markedly built environment around the Externsteine.[69] Possibly a century or more later, the forgery similarly refers to the woods around the Externsteine as nemus—a legal word for forest, implying a cultivated and maintained woodland, rather than the inaccessible silva.[70] Archeological finds such as an equestrian spur even point to the possibility of a high medieval manor house in the area.[71] So from at least 1119, and through its definitive development into a hermitage, the Externsteine were neither secluded nor undeveloped, and so it is not a question of access—which would limit the possibilities to the Lord of Lippe—but of motivation.

Although I am inclined towards the evidence for Bernhard II, I wish to make an important caveat: Just because surviving stone carvings at Werden are not equal to the quality of the Deposition does not mean the Werden Abbots, who were already at this time Prince-Abbots, could not hire carvers closer to Paderborn. Paderborn itself, whether Abdinghof or the cathedral, was by the late twelfth century in a building boom between the great sculpted southern porch of the cathedral and the massive thirteenth-century renovation, meaning labor would certainly have been available.[72] Most importantly, an expansion to the Externsteine caves, an added upper chapel, and a sculptural campaign would have been costly. This raises the question of who stood to benefit. Recorded dues into the Late Middle Ages suggest there was never much to gain financially for owning the Externsteine.[73] Without a parish or even a small hamlet around the site, there seems little incentive for the Lippe lords to invest. On the other hand, monasteries frequently went to expensive lengths to transform and expand liturgical sites, an investment that was seldom returned in immediate income but rather in more firmly establishing their relevance, patronage, and hold over property, thus assuring their long-term survival, especially when ownership might become contested.[74] This logic suggests why the Abbots of Werden would have invested in a first phase of development around 1115, and why, if the second expansion was compelled by Bernhard II, it was definitively after his monastic vows in 1198. Only a monk (with strong ties to his wealthy secular heirs) would direct this kind of munificence towards a money- and land-losing venture.

The sequence of the medieval interventions thus appears to be a first phase, completed by 1119 by the Abbots of Werden, in which a cave system was established and a suggestive reference to the Holy Sepulcher was added in the form of an empty tomb. Already at this point the consecrated altar required the maintenance of a professional religious and the space was appropriate for a hermit. A second expansion near the end of century, probably initiated by the former Lord of Lippe, now a Cistercian brother, included the carved Apostles and Deposition, that aimed to double down on the identity of the space as an imagined Jerusalem.

Hermitage and Holy Sepulcher

The extent to which the Externsteine were genuinely perceived as a replica of the Holy Sepulcher is contested. Jürgen Krüger has rightly noted that the caves and tomb would constitute the least literal way one could possibly reference the Jerusalem structure.[75] With no built architecture and no references to the quintessential concentricity of the rotunda or the layout of the altars, the Externsteine are a far cry from the Holy Sepulchers of Fulda, Eichstätt, or Bishop Meinwerk of Paderborn’s Busdorfkirche, lost to a fire in 1228.[76] In the case of the carved Deposition, it might even be easier to equate it instead to the life-sized wooden deposition groups made at this time in Spain and Italy, which similarly evoke an imaginative transportation in time and space, but through the liturgy rather than any bodily experience.[77]

But, as Krüger also hints, if the stones are not a “replica” of the Holy Sepulcher, they still undoubtedly refer to the Holy Land.[78] This is done not just through the empty tomb and later Deposition but through the site’s relationship to eremitism. The pull of the eastern Mediterranean desert was a major force in Western religious experience, even enshrined in the opening chapter of the Benedictine Rule, and its allure rose again as access to the Holy Land increased after 1099.[79] Yet for those in religious orders, leaders including Peter Damian, Anselm of Canterbury, and Bernard of Clairvaux all discouraged pilgrimage as an unnecessary distraction.[80] William of Malmesbury even recounts how bishop Wulfstan of Worcester once shamed a certain Ealdwine for trying to give up “the life of a hermit in the wild woods” so he might find easier glory in the costly trip to the Lord’s Sepulcher.[81] For William, the hermetic cell is not only an ersatz Holy Sepulcher, it is a catalyst for more intellectually and spiritually impactful engagements with the Holy Land. The presence of hermits would therefore have implicitly tied the Externsteine to the Holy Land.

Fig. 17. Detail of a map of Jerusalem, Cambrai, Bibliothèque municipale 0466 (0437), fol. 1r. Photo: Le Labo, Cambrai, CC BY-NC 3.0.

Even if there were no hermits as early as the twelfth century, it would have been the caves, hollowed out around 1115 and expanded around 1190, that offered twelfth-century Europeans the most potent facsimile of the Holy City. By the 1170s, western travelers to Jerusalem, like the cleric John of Würzburg, regaled readers with florid descriptions of caves full of hermits lining the Valley of Jehosaphat and Kidron Valley beyond the city’s eastern walls.[82] Other descriptions from the same period advertised a veritable “street of hermits” (vicus heremitarum) lining the way to the tomb of Absalom, a feature depicted in one mid-twelfth-century map as a series of cave entrances (Fig. 17).[83] Inspired by these eremi cultores, some visitors, like the English merchant Godric of Finchdale, deliberately returned to Europe to find caves of their own.[84] Even in the popular imagination, the Externsteine caves, by dint of being caves, evoked the eremitic landscape of the Holy Land—whether or not there were actual hermits present.

In the case that there were hermits, though, the cave-as-Jerusalem metaphor begins to take on the more specific meaning of cave-as-tomb. As Tom Licence has shown, at the extreme end of reclusion there is a “distinctive allegory, which cast the recluse’s cell as a sepulchre and the act of entering it as a descent into the tomb.”[85] Totally enclosed hermits (inclusi) were shut off with the recitation of the Office of the Dead. They were seen as liturgically deceased, buried with Christ in his tomb.[86] It is the hermit, therefore, that holds the potential to transform an imagined Jerusalem most fully into a Holy Sepulcher.

The Holy Land, Holy Sepulcher, and hermitage thus go hand in hand. This symbiosis explains the compatibility of the Externsteine’s public and “wild” identities. Eremitism in the Latin West may be based on the idea of desert, but in practice, by the eleventh and twelfth centuries most hermits, especially anchorites, were so closely interwoven with cenobitic monasticism that they were usually attached, sometimes literally, to churches or monasteries.[87] Their (theoretical) distance from society endowed them with an objectivity and wisdom that, ironically, made them much sought out by surrounding communities.[88] The desert wilderness and isolation that surround eremitism was therefore as much imaginary as the Holy Sepulcher in which some anchorites were entombed.

The final question to ask, then, is why a monumental carving of the Deposition was desirable in the late twelfth century. Seen from the road to the east, the massive painted carving would have been highly unusual and thus attractive at a distance. Pieper believes that this attraction was part of a transformation of the Externsteine into a stage for an annual Passion Play.[89] There is not sufficient evidence to confirm this use of the space, but it is still possible to imagine the sculpture as a highly public and performative backdrop, drawing attention to the site as an imagined Jerusalem (in this case, the setting of the play). Sauerländer, in the same article in which he refers to the Externsteine as a wild mountain Golgotha, reminds that the carved images proliferating on the exterior of religious spaces in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries served primarily to prepare the faithful for their experiences within.[90] So public and powerful a medium was monumental sculpture that Sauerländer ultimately equates the Externsteine Deposition to a Las Vegas marquee. The arcosolium, which faced the original road (today the pond), is indistinguishable when approaching from the northeast. It was perhaps deemed insufficient by 1190 to fully prepare a lay audience for the transformative experience of, not just an ersatz Holy Land, but the Holy Sepulcher. The Deposition image, on the other hand, loudly announces the transformation of the Externsteine from an eremitic representation of Jerusalem to the tomb of Christ himself. The choice of a Deposition with a resurrected Christ—perhaps inspired by Eastern models but constructed from centuries-old Western iconography—amplifies the narrative potency of the preexisting empty tomb. Together, the two features concentrate the narrative on the events after Christ’s death, centering on the Sepulcher. The more public-facing Deposition therefore did not change the meaning of the space but amplified what was already there, making it more accessible to a broader public.

The Externsteine undoubtedly carried multiple meanings and functions simultaneously and non-exclusively, but since at least 1119 they were almost always public and accessible. They in many ways anticipate other major public wayside monuments that would come to mark the European landscape and passage through it in the later Middle Ages.[91] It is not that the caves and sculptures lent themselves to later being a Holy Sepulcher or that the references to the Holy Sepulcher lent themselves to later becoming a hermitage; it was the site’s identity as both an imagined Holy Sepulcher and hermitage, both a major public shrine and a wilderness retreat, that mutually reinforced one another from the beginning.[92] The Deposition image is seemingly part and parcel with that purpose, amplifying an identity that was already suggested by the tomb.

A parish church never existed at the Externsteine because, despite the excellent location, cultivated surroundings, and long-distance road, there was never a village or monastery closer than two kilometers away in Horn. There was therefore never a permanent public engaging habitually with the monument, making it easy in retrospect to mistake the stones as a wild cult site. The fact that the tradition of eremitism asks that hermits be identified with the wooded deserta of society’s fringes only contributed in retrospect to making the Externsteine appear so. It is in this way that the ascetic tradition shapes both elite and popular perception of the landscape, creating wilderness, rather than finding it. The Externsteine are instead a wayside monument, a hermitage, and an imagining of the Holy Sepulcher, all of which reinforce each other. None of these purposes reveal the landscape to be anything other than carefully cultivated, a testament to the delusionary conditioning culture plays on our perceptions of “nature.”[93]

Perhaps to the first inhabitants, the caves suggested themselves as wild, but it was human intervention that made them so. The reluctance to raise this challenging realization for centuries ultimately opened the stones to conspiracies of a Germanic wilderness and the unsavory politics that still cling to it today. Ironically, though, creative imaginings of the Externsteine are what most unite the stones’ medieval hermits and modern solstice celebrants like the tattooed man. Fittingly, his righted “Irminsul” and Hermannsdenkmal are flanked by a runic alphabet that one would assume stems from either a medieval Germanic Futhark or one of their modern occultist derivatives (see Fig. 4). Upon closer inspection, however, it appears that the letters are just a reimagining of the familiar 26-letter Latin alphabet in a runic style—an historical amalgam meant to create a past more legible to certain desires in the present.

The man’s ancestors may not have observed the summer solstice at the Externsteine, but they still celebrated under the stones’ shadows, enthralled by their natural beauty and their marking of the passage of time. Since at least 1394, the lords of Lippe hosted an occasional Meyghoyge to dem Egestersteyne, a mayday festival celebrating the season of rebirth and growth.[94] Centuries of revelers have been transfixed by the surprising architectural feat of nature and so invented ways to pay homage to them. It is impossible to say whether this later history of fetishizing the landscape around the Externsteine would have been possible if it were not once a hermitage. The insistent romanticism surrounding hermits and wilderness, established in Late Antiquity and propelled by the Reformation, opened the door to the exploitation still ongoing today. But exploitation can cut both ways. The Externsteine now lie in a protected nature preserve; no more natural than it ever was, but hopefully closer to the ecological goals of worshippers both medieval and modern.

References

| ↑1 | I wish to thank Stefanie Haupt and Roland Linde for generously sharing with me their unparalleled expertise on the histories, medieval and modern, of the Externsteine. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Jürgen Krüger, “Ein Heiliges Grab an den Externsteinen?,” in Die Externsteine: Zwischen wissenschaftlicher Forschung und völkischer Deutung, ed. Larissa Eikermann, Stefanie Haupt, Roland Linde, and Michael Zelle (Münster: Aschendorff, 2015), 139–177. |

| ↑3 | There is a vast and growing literature on the various imaginings of Jerusalem in medieval Europe. Recent contributions include Bianca Kühnel, Neta Bodner, and Renana Bartal, ed. Projections of Jerusalem in Europe (Leuven: Peeters, 2023); Bianca Kühnel, Jerusalem Icons in the European Space (Lueven: Peeters, 2022); Robin Griffith-Jones and Eric Fernie, Tomb and Temple: Re-imagining the Sacred Buildings of Jerusalem (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2018); and Lucy Donkin and Hanna Vorholt, Imagining Jerusalem in the Medieval West (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012). |

| ↑4 | Wilibald Sauerländer, “Romanesque Sculpture in its Architectural Context,” in The Romanesque Frieze and its Spectator, ed. Deborah Kahn (London: H. Miller, 1992), 17–44. |

| ↑5 | Simon Schama, Landscape and Memory (New York: Vintage, 1996), 75–120. |

| ↑6 | Ute Halle, “Die Ausgrabungen an den Externsteinen 1934/35 im Spannungsfeld wissenschaftlicher, völkischer und politischer Interessen,” in Die Externsteine: Zwischen wissenschaftlicher Forschung und völkischer Deutung, ed. Larissa Eikermann, Stefanie Haupt, Roland Linde, and Michael Zelle (Münster: Aschendorff, 2015), 335–355. |

| ↑7 | “domus recluse,” Franz Flaskamp, ed., Externsteiner Urkundenbuch (Gütersloh: Flöttmann, 1966), no. 9, 44. |

| ↑8 | “Non in urbibus volo remanere, sed potius in locis desertis et incultis.” The line is attributed to Norbert of Xanten, Herman, Liber III de Miraculis S. Mariae Laudunensis, Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Scriptores (SS) (Hannover: Hahnsche Buchhandlung), bk. 12, 656; on the distinction between a recluse (inclusa/inclusus) and hermit (eremita), and the umbrella term “anchorite,” see Tom Licence, Hermits and Recluses in English Society, 950–1200 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 8–19. |

| ↑9 | Henrietta Leyser, Hermits and the New Monasticism: A Study of Religious Communities in Western Europe 1000–1150 (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1984), 18–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-17589-5_3; C. H. Lawrence, Medieval Monasticism: Forms of Religious Life in Western Europe in the Middle Ages, 4th ed. (London and New York: Routledge, 2015), 135–145. On ideal locations for monasteries see Dieter van der Nahmer-Ahrensburg, “Über Ideallandschaften und Klostergründungsorte,” Studien und Mitteilungen zur Geschichte des Benediktiner-Ordens und seiner Zweige 84 (1973): 195–270. |

| ↑10 | Ellen F. Arnold, Negotiating the Landscape: Environment and Monastic Identity in the Medieval Ardennes (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013); Christopher Zwanzig, Gründungsmythen fränkischer Klöster im Früh und Hochmittelalter (Stuttgart: Steiner, 2010); Maximilian Diesenberger, “Die Überwindung der Wüste: Beobachtungen zu Rahmenbedingungen von Klöstergründungen im frühen Mittelalter,” in Die Suche nach dem verlorenen Paradies: Europaïsche Kultur im Spiegel der Klöster, ed. Elisabeth Vavra (St Pölten: Niederösterreichisches Landesmuseum, 2000), 87–92; Chris Wickham, European Forests in the Early Middle Ages: Landscape and Land Clearance,” in Land and Power: Studies in Italian and European Social History, 400–1200 (London: British School at Rome, 1994), 155–199; van der Nahmer-Ahrensburg, “Über Ideallandschaften,” 195–270. |

| ↑11 | This post-medieval history of the Externsteine has been well researched and recently published in a comprehensive volume far more extensive than what can be given here, Larissa Eikermann, Stefanie Haupt, Roland Linde, and Michael Zelle, ed. Die Externsteine: Zwischen wissenschaftlicher Forschung und völkischer Deutung (Münster: Aschendorff, 2015). |

| ↑12 | Laura Wright, Wilderness into Civilized Shapes: Reading the Postcolonial Environment (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2010). |

| ↑13 | As communicated to me in conversation on June 20, 2024. Many of these sentiments echo the findings of Helen A. Berger, “The Environmentalism of the Far-Right Pagans: Blood, Soil, and the Spirits of the Land,” Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture 17.4 (2023): 481–500. https://doi.org/10.1558/jsrnc.24203. |

| ↑14 | The oculus faces northeast, meaning it frames most sunrises in spring and summer. It is tellingly the Easter sunrise that has been shown to be more directly aligned with the orientation of the oculus from the standpoint of the center of the chamber but there is a deep and well-founded skepticism around archeoastronomy generally among archeologists, Stefanie Haupt and Dana Schlegelmilch, “Archäoastronomie: eine wissenschaftshistorische Annäherung,” in Die Externsteine: Zwischen wissenschaftlicher Forschung und völkischer Deutung, ed. Larissa Eikermann, Stefanie Haupt, Roland Linde, and Michael Zelle (Münster: Aschendorff, 2015), 511–531. |

| ↑15 | Stefanie von Schnurbein, “Religion of Nature or Racist Cult? Contemporary Neogermanic Pagan Movements in Germany,” in Antisemitismus, Paganismus, Völkische Religion, ed. Hubert Cancik and Uwe Puschner (Munich: K. G. Sauer, 2004), 135–150. |

| ↑16 | This belief was popularized by völkisch lay-archeologist Wilhelm Teudt in his Germanische Heiligtümer: Beiträge zur Aufdeckung der Vorgeschichte (Jena: E. Diederichs, 1929), 47–55. On its origins, Stefanie Haupt and Julia Schafmeister, “Wilhelm Teudts Deutung des Kreuzabnahmereliefs an den Externsteinen als Beispiel völkischer Irminsul-Rezeption,” in Marsberg und die Irminsul. Neue Forschungen zum Beginn der Sachsenkriege Karls des Großen 772, ed. Burkhard Beyer and Roland Linde (forthcoming). |

| ↑17 | On the Externsteine as, more specifically, a far-right lieu de mémoire, Karl Banghard, “‘Germanische’ Erinnerungsorte: Geahnte Ahnen,” in Erinnerungsorte der extremen Rechten, ed. Martin Langebach and Michael Sturm (Wiesbaden: Springer, 2015), 61–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-00131-5_3. |

| ↑18 | Stefanie Haupt, “Walther Machalett und die Entstehung des ‘Forschungskreises Externsteine’,” Rosenland: Zeitschrift für lippische Geschichte 15 (2013): 77–102. |

| ↑19 | Walther Machalett, Die Externsteine. Das Zentrum des Abendlandes. Die Geschichte der weißen Rasse (Maschen: Hallonen-Verlag, 1970). |

| ↑20 | Jeffrey D. Lavoie, “Theosophical Chronology in the Writings of Guido von List (1848–1919): A Link Between H.P. Blavatsky’s Philosophy and the Nazi Movement,” in Innovation in Esotericism from the Renaissance to the Present, ed. Georgiana D. Hedesan and Tim Rudbøg (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2021), 255–279. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-67906-4_10. |

| ↑21 | Stefanie von Schnurbein, Norse Revival: Transformations of Germanic Neopaganism (Leiden: Brill, 2016), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004309517. |

| ↑22 | Kan Raabe and Karsten Wilke, “Die Externsteine und die extreme Rechte: Von Interpreten, Mittlern und Rezipienten,” in Die Externsteine: Zwischen wissenschaftlicher Forschung und völkischer Deutung, ed. Larissa Eikermann, Stefanie Haupt, Roland Linde, and Michael Zelle (Münster: Aschendorff, 2015), 497–502. See also, Stefanie von Schnurbein, Religion als Kulturkritik: Neugermanisches Heidentum in 20. Jahrhundert (Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag, 1992), 250–252. |

| ↑23 | Walther Matthes and Rolf Speckner, Das Relief an den Externsteinen: ein karolingisches Kunstwerk und sein spiritueller Hintergrund (Ostfildern: Ed. Tertium, 1997). |

| ↑24 | “…kleinsten gemeinsamen Nenner,” Stefanie Haupt, “‘Nicht keiner Seite hin gebunden?’ Walther Machalett und der ‘Forschungskreis Externsteine’,” in Die Externsteine: Zwischen wissenschaftlicher Forschung und völkischer Deutung, ed. Larissa Eikermann, Stefanie Haupt, Roland Linde, and Michael Zelle (Münster: Aschendorff, 2015), 451–475. |

| ↑25 | Ter Ellingson, The Myth of the Noble Savage (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), esp. 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1525/california/9780520222687.003.0001. |

| ↑26 | “Naturnahes,” cited in a blog responding to the publication by Mathias Wenger, “Die Kreise Paderborn und Höxter als Anlaufstelle für national-völkisch gesinnte Esoteriker?,” http://www.derhain.de/TanfanaGoettinderMarser.html [last accessed April 30, 2025]. |

| ↑27 | Erich Kittel, Die Externsteine: Tummelplatz der Schwarmgeister? (Detmold: Naturwissenschaftliche und Historische Verein Lippe, 1965). |

| ↑28 | Tacitus, Histories: Books 4–5. Annals: Books 1–3, trans. Clifford H. Moore and John Jackson (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1931), bk. 1, ch. 61, 348–349. |

| ↑29 | Uta Halle, ‘Die Externsteine sind bis auf weiteres germanisch!’ Prähistorische Archäologie im Dritten Reich (Bielefeld: Verlag für Regionalgeschichte, 2002). |

| ↑30 | Bernd-A. Rusinek, “‘Wald und Baum in der arisch-germanischen Geistes- und Kulturgeschichte’. Ein Forschungsprojekt des ‘Ahnenerbe’ der SS 1937–1945,” in Der Wald—Eine deutsche Mythos? Perspektiven eines Kulturthemas, ed. Albrecht Lehmann and Klaus Schriewer (Berlin: Reimer, 2000), 267–363. |

| ↑31 | Halle, “Die Ausgrabungen an den Externsteinen 1934/35,” 340–349. |

| ↑32 | Cited in Halle, “Die Ausgrabungen an den Externsteinen 1934/35,” 366–367. |

| ↑33 | Larissa Eikermann, Die Externsteine in der Kunstvermittlung: Eine Studie zur regionalen Kulturbebildung (Baden-Baden: Tectum, 2019), 153–164. https://doi.org/10.5771/9783828872745. |

| ↑34 | Johann Wolfgang Goethe, “Die Externsteine,” Ueber Kunst und Alterthum, vol. 5, no. 1 (Stuttgart: Cottaischen, 1824), 130–139. |

| ↑35 | “…konnte es nicht fehlen daß nach einiger Beruhigung der Welt bei Ausbreitung des christlichen Glaubens zu Bestimmung der Einbildungskraft die Bilder im nördlichen Westen gefordert…” Goethe, “Die Externsteine,” 131. |

| ↑36 | Uwe Puschner, Die völkische Bewegung im wilhelminischen Deutschland. Sprache, Rasse, Religion (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 2001); and Stefan Breuer, Die Völkischen in Deutschland. Kaiserreich und Weimarer Republik, 2nd ed. (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft 2012). |

| ↑37 | See the many contributions to Uwe Puschner, Walter Schmitz, and Justin H. Ulbricht, ed., Handbuch zur “Völkischen Bewegung” 1871–1918 (Munich: K. G. Saur, 1996). |

| ↑38 | “Horna oppidum campos et agros jucundos habet. Et ex vicina rupe Picarum, antiquo monumento, cujus veteres scriptores mentionem fecerunt, claret. Legi aliquando, quod ex rupe illa picarum, idolo Gentilitio, fecerit Carolus magnus altare Deo sacratum et ornatum effigiebus Apostolorum.” Hermann Hamelmann, Opera Genealogico-Historica de Westphalia et Saxonia (Lemgo: Henrici Wilh. Meyeri, 1711), 79. |

| ↑39 | “Est magna quedam rupes inter civitatem Paderbornensem et oppidum Hornnense. In qua rupe sacellum est excisum quod Exsterensteyn vulgo vocatur. Hoc inhabitarunt usque ad nostra tempora clusarii sive heremite, qui deprehensi latrones fuisse expulsi et extirpati sunt.” Flaskamp, Externsteiner Urkundenbuch, 29. |

| ↑40 | Johannes Piderit, Chronicon Comitatus Lippiae (Rinteln an der Weeser: Lucius, 1627), 525–526. |

| ↑41 | “Das ist zwar von den Alten auß guter Andacht und Wolmeinunge geschehen aber die Posteri und Nachkommen haben es mißbrauchet.” Piderit, Chronicon Comitatus Lippiae, 525. |

| ↑42 | Klemens Honselmann, “Unbekannte Urkunden über das Benefizium an den Externsteinen,” Westfälische Zeitschrift 96 (1940): 85–92. |

| ↑43 | Flaskamp, Externsteiner Urkundenbuch, 24, and no. 89, 97. |

| ↑44 | Uta Halle does reserve the caveat that there could have been habitation as early as the Carolingian period, but she expressly dismisses any possibility of there being a pre-Christian function to the site before that, Halle, “Die Ausgrabungen an den Externsteinen 1934/35.” |

| ↑45 | Roland Linde, “Die Externsteine in der urkundlichen Überlieferung des Mittelalters,” in Die Externsteine: Zwischen wissenschaftlicher Forschung und völkischer Deutung, ed. Larissa Eikermann, Stefanie Haupt, Roland Linde, and Michael Zelle (Münster: Aschendorff, 2015), 43–76. |

| ↑46 | The final digit is too weathered to be definitive. Helga Giersiepen, “‘Original’ oder ‘Fälschung’? Die Inschrift in der unteren Grotte der Externsteine,” in Die Externsteine: Zwischen wissenschaftlicher Forschung und völkischer Deutung, ed. Larissa Eikermann, Stefanie Haupt, Roland Linde, and Michael Zelle (Münster: Aschendorff, 2015), 77–96. |

| ↑47 | Though arguments have been raised for dating the forgery to the 1160s, Flaskamp’s belief that the letter dates closer to c. 1300 is still compelling, Flaskamp, Externsteiner Urkundenbuch, 9–37. |

| ↑48 | Flaskamp, Externsteiner Urkundenbuch, 30–31. |

| ↑49 | Flaskamp, Externsteiner Urkundenbuch, 33; Rudolf Kötzschke, Rheinische Urbare: Sammlung von Urbaren und anderen Quellen zur rheinischen Wirtschaftsgeschichte, Bd. 2: Die Urbare der Abtei Werden an der Ruhr (Bonn: Behrendt, 1906), no. 17, 184. |

| ↑50 | Flaskamp, Externsteiner Urkundenbuch, 33. |

| ↑51 | Robin Jähne, Roland Linde, and Clemens Woda, Licht in das Dunkel der Vergangenheit: Die Lumineszenzdatierung an den Externsteinen (Bielefeld: Verlag für Regionalgeschichte, 2007). |

| ↑52 | Roland Pieper, “Inszenierungen zwischen Karfreitag und Ostern: Mediale Aspekte zum Ensemble der Externsteine,” in Die Externsteine: Zwischen wissenschaftlicher Forschung und völkischer Deutung, ed. Larissa Eikermann, Stefanie Haupt, Roland Linde, and Michael Zelle (Münster: Aschendorff, 2015), 97–138. |

| ↑53 | Roland Linde and Ulrich Meier, “Wann und in wessen Auftrag wurden die Externsteine-Anlagen und das Kreuzabnahmerelief geschaffen?,” in Die Externsteine: Zwischen wissenschaftlicher Forschung und völkischer Deutung, ed. Larissa Eikermann, Stefanie Haupt, Roland Linde, and Michael Zelle (Münster: Aschendorff, 2015), 267–292. |

| ↑54 | Though Linde argues convincingly that a dedication could have occurred as early as 1200, the earliest confirmed example of a Holy Cross altar in the area, the Drüggelter Kapelle outside nearby Soest, first appears in sources in 1227 but was not identified as a Holy Cross chapel until 1338, Georg Dehio, Handbuch der Deutschen Kunstdenkmäler: Nordrhein-Westfalen II: Westfalen, 3rd ed. (Berlin: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2016), 694. On the first identification of an Externsteine Holy Cross chapel in 1429, Johannes Mundhenk, “Der Ertrag zweier an den Papst gerichteter Suppliken von 1429/30 für die Geschichte der Externsteiner Kapelle,” Westfälische Zeitschrift 126/127, (1976/1977): 201–227. |

| ↑55 | Harriet M. Sonne de Torrens, “A Legacy of Resistance: The Case of the Freckenhorst Baptismal Font,” Iconographisk Post: Nordic Review of Iconography 3.4 (2019), 4–45. https://doi.org/10.69945/ico.vi3-4.25650. |

| ↑56 | Uwe Lobbedey, Romanik in Westfalen (Würzburg: Zodiaque, 1999), 342–371. |

| ↑57 | Christoph Stiegemann, ed., Diözesanmuseum Paderborn: Werke in Auswahl (Petersberg: Imhof, 2014), no. 1, 28–30. |

| ↑58 | Johannes Mundhenk, “Zur Datierung des Externsteiner Kreuzabnahmereliefs innerhalb der Kunstgeschichte,” Westfälische Forschungen 35 (1985): 40–59. |

| ↑59 | Peter Barnet, Michael Brandt, and Gerhard Lutz, ed., Medieval Treasures from Hildesheim (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013), no. 15, 58. Another Byzantine example, British Museum 1856,0623.21, is said to have been found in Germany. |

| ↑60 | This identification was first suggested by Alois Fuchs, Im Streit um die Externsteine: ihre Bedeutung als christliche Kultstätte (Paderborn: Bonifacius, 1934); on the growing cult of the Tree of the Cross and its expression in art, Barbara Baert, A Heritage of Holy Wood: The Legend of the True Cross in Text and Image, trans. Lee Preedy (Leiden: Brill, 2004), esp. 54–132. |

| ↑61 | Elizabeth Parker, “The Descent from the Cross” (unpublished dissertation, New York University, 1975), 6 and 172; there is at least one earlier example in sculpture, a tympanum with the Deposition from Foussais Saint-Hilaire dating 1061. Around c. 1225, the sun and moon appear in a Crucifixion on the tympanum of the Hohnekirche in nearby Soest and in an image of the Deposition, in the Brandenburg Evangeliar, Brandenburger Domstiftsarchiv MS 1. |

| ↑62 | “fast einzigartig.” Erwin Panofsky, Die deutsche Plastik des elften bis dreizehnten Jahrhunderts (Munich: Kurt Wolff, 1924), 84. |

| ↑63 | Parker, “The Descent from the Cross,” 172. |

| ↑64 | Emanuel S. Klinkenberg, Compressed Meaning: The Donor’s Model in Medieval Art to around 1300 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2009). |

| ↑65 | Rainer Budde, Deutsche Romanische Skulptur 1050–1250 (Munich: Hirmer, 1979), 49. The figure has been historically identified as Adalbert of Zollern, but there were three male founders of the monastery and no convincing arguments have been put forward for any one in particular, Ulrike Kalbaum, Romanische Türstürze und Tympana in Südwestdeutschland: Studien zu ihrer Form, Funktion und Ikonographie (Münster: Waxmann, 2011) 185–192. The figure’s dress is notably distinct from the more elaborate dress of kneeling secular donors from the period, for example on tympana from the Basel Galluspforte, Windberg Abbey, or the Jaksa Michael chapel in Ołbin, Wrocław. For more see Robert A. Maxwell, “The ‘Literate’ Lay Donor: Textuality and the Romanesque Patron,” in Romanesque Patrons and Processes: Design and Instrumentality in the Art and Architecture of Romanesque Europe, ed. Jordi Camps, Manuel Castiñeiras, John McNeill, and Richard Plant (Routledge: New York, 2018), 259–277. |

| ↑66 | Milena Bartlová, “In Memoriam Defunctorum: Visual Arts as Devices of Memory,” in The Making of Memory in the Middle Ages, ed. Lucie Doležalová (Leiden: Brill, 2010), 478. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004179257.i-500.87. |

| ↑67 | “Wer also hätte hier ein solches Relief erstellen können—in der Einsamkeit der lippischen Wälder, nicht an einer bedeutenden Kirche in den Zentren politischer Macht?” Pieper, “Inszenierungen zwischen Karfreitag und Ostern,” 111. |

| ↑68 | Flaskamp, Externsteiner Urkundenbuch, 30–31. |

| ↑69 | Johannes Mundhenk, Forschungen zur Geschichte der Externsteine, Bd. III: Quellen zur mittelalterlichen Geschichte der Externsteine (Lemgo: Wagener, 1980), 59–77. |

| ↑70 | Markus Friederich Jeitler, “Wald und Waldnutzung im Frühmittelalter,” in Das Mittelalter 13 (2008): 12–27. https://doi.org/10.1524/mial.2008.0014. |

| ↑71 | Halle, Die Externsteine sind bis auf weiteres germanisch!, 322–26. |

| ↑72 | Uwe Lobbedey, “Der Paderborner Dom: die Geschichte seiner Erbauung im 13. Jahrhundert,” in Gotik: der Paderborner Dom und die Baukultur des 13. Jahrhunderts in Europa (Petersberg: Michael Imhof, 2018), 90–121. |

| ↑73 | Franz Flaskamp, “Der Externsteiner Beneficiat Konrad Mügge,” Lippische Mitteilungen aus Geschichte und Landeskunde 22 (1953): 154–162. |

| ↑74 | For a classic example, Penelope D. Johnson, Prayer, Patronage, and Power: The Abbey of la Trinité, Vendôme, 1032–1187 (New York: New York University Press, 1981). |

| ↑75 | Krüger, “Ein Heiliges Grab an den Externsteinen?,” 139–177. |

| ↑76 | Notker Baumann, “Die Anastasis-Rotunde der Fuldaer Michaelskirche und ihre spätantike bzw. frühmittelalterliche Inspiration,” Archiv für mittelrheinische Kirchengeschichte 75 (2023): 601-660. Diarmuid Ó Riain, “An Irish Jerusalem in Franconia: the Abbey of the Holy Cross and Holy Sepulchre at Eichstätt,” Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature 112 (2012): 219-270. https://doi.org/10.1353/ria.2012.0000. Sveva Gai, Claudia Dobrinski, Clemens Kosch, Sven Spiong, and Martin Kroker, “Die Siedlungsentwicklung Paderborns im 11. und frühen 12. Jahrhundert im Kontext der westfälischen Bischofsstädte,” in Canossa 1077: Erschütterung der Welt, ed. Christoph Stiegemann and Matthias Wemhoff (Munich: Hirmer, 2006), 251-264, and on the now-classic understanding of architectural references to the Holy Sepulcher via concentricity, Richard Krautheimer, “Introduction to an ‘Iconography of Mediaeval Architecture,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 5 (1942): 1-33. https://doi.org/10.2307/750446. |

| ↑77 | Mathias Delcor, “L’Iconographie des descents de croix en Catalogne, à l’époque romane. Description, origine, et signification,” Cahiers de Saint-Michel-de-Cuxa 22 (1991): 179–202; Bernd Schälicke, “Die Ikonographie der monumentalen Kreuzabnahmegruppen des Mittelalters in Spanien,“ (unpublished dissertation, Freie Universität Berlin, 1975). |

| ↑78 | “Nachbildung.” Krüger, “Ein Heiliges Grab an den Externsteinen?,” 152. |

| ↑79 | Giles Constable, Monks, Hermits and Crusaders in Medieval Europe (London: Variorum, 1980), 254–257. |

| ↑80 | Giles Constable, Religious Life and Thought (11th–12th Centuries) (London: Variorum, 1979), 127–134. |

| ↑81 | “Alduuinus erat quidam ab eo factus monachus, isque in uastis simo illu saltu quod Maluernum uocatur heremiticam uitam cum Guidone sotio exercebat. Guidoni post longos agones compendiosius ad gloriam uisam ut Ierosolimam iret, ubi labore itinerario uel Dei sepulcrum uiderat uel felicem manu Saracenorum mortem anticiparet.” William of Malmesbury, Gesta Pontificum Anglorum, ed. and trans. Michael Winterbottom (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2007), bk. 4, ch. 145, 434–5; Laura Slater, “Recreating the Judean Hills? English Hermits and the Holy Land,” Journal of Medieval History 42.5 (2016): 603–626. . https://doi.org/10.1080/03044181.2016.1219271. |

| ↑82 | Denys Pringle, The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem, vol. 3 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 434–435; John Wilkinson, Joyce Hill, and W. F. Ryan, ed., Jerusalem Pilgrimage, 1099–1185 (London: Hakluyt Society, 1988), 270. |