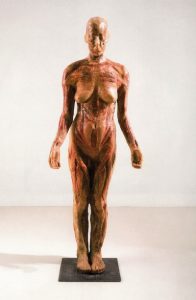

Kiki Smith, Untitled (Heart), 1986

I’ve had an obsession with the work of Kiki Smith for some time. I think it was always there, nascent since my first introductory art history course decades ago, but really flourished after I saw a retrospective of her work at SFMOMA in 2005. I was in the throes of completing my dissertation (on twelfth-century images of the fragmented/manipulated/violated female body), and I was nearly rendered speechless by a number of her pieces that seems to be speaking specifically TO ME about the objects on which I was writing. She offers a physical and material (rather than textual) theory of visual, even phenomenological, experience. Her work literally shows her feminist critiques, forcing its viewers to physically experience both trauma and recuperation. How could she have known? How is she saying it so much more eloquently than I? How do I explain this, this non-verbal articulation, this capturing of phenomenological potential?

I struggled to figure out a way to acknowledge her devastatingly perfect commentary in my dissertation; the result was a rather unsatisfying nod in my dissertation’s conclusion. A few years later I presented a paper on Smith at the medieval conference at Kalamazoo, and the (small) audience was receptive. But in the days after, when explaining to strangers or acquaintances what I presented on, I was often met with responses of confusion or dubiousness about the legitimacy of an interpretive framework created by a contemporary artist, by objects in space rather than words on a page. I kept wondering, was this really such a radical or ridiculous idea?

Kiki Smith, Virgin Mary, 1992

And now she reappears on my radar, through a remarkably convoluted route. In preparation for one of my presentations on the Staffordshire Hoard at the recent Babel conference, I was talking to artists, especially metalsmiths. One of these was a current student at OSU (where I teach), a jewelry/metals artist who recently returned from a truly fabulous internship in New York (www.ulae.com), through which she made connections that resulted in her working in Kiki Smith’s studio. As I talked to this student about metalsmithing techniques and materials, I couldn’t resist also asking her about working with Smith. And it made me want to think again about Smith’s relationship to medieval culture and her intensely phenomenological methods.

As I find myself returning to this material, wondering again what I really want to say about Smith’s medievalisms, my earlier ideas start to strike me as both obvious and terribly unradical, perhaps not even worthy of serious scholarly consideration. What has changed, and when did it change? It seems that just like that, we find ourselves in a climate that is much more welcoming to this kind of work. Or is it just that I am repositioned? Is it me, or my surroundings? Nature or nurture? Has the scholarly environment really been altered, or have I altered my relationship with it, with others in the field? Have I simply surrounded myself with like-minded perspectives, which have drowned out the doubters?

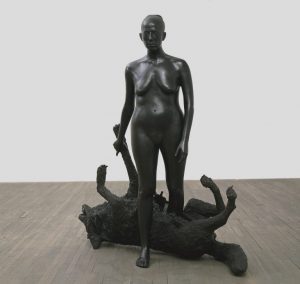

Kiki Smith, Rapture, 2001

I do think there are more things to say about Smith, and I really want to be the one to say them. But I’m also fascinated by the way this idea has shifted around in my scholarly bag of tricks – it is a project that had to wait for the right time, that was not ready, that might be ready now, or maybe the moment has already passed. It also says something about how our field is morphing, right now, shapeshifting before our eyes, like a creature from one of Smith’s pieces. This conjures something about how research and writing are life-long endeavors – sometimes the circumstances are beyond your control, but the circumstances are also virtually guaranteed to change.