Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

The premise of the conference, as set out by Aden Kumler in her introductory remarks, was that the field of medieval art history is now at a point “after” the “interdisciplinary turn.” Here “after” is to be understood along the same lines as “post” in now-familiar terms such as postmodernism and post-colonialism: meaning not that interdisciplinarity is now somehow passé for medieval art historians, but instead that it has become so fully integrated into the field as to be taken for granted by its practitioners. The question posed by the conference, then, was what comes next for us “after” the emphasis on interdisciplinarity? One seemingly obvious answer is a renewed sense of “disciplinarity:” but what would or should a newly “disciplined” medieval art history look like? How would it be different from what came before the “interdisciplinary turn” and so how would this next turn in the field be something other than a return to its past? And what would it have to offer both to interdisciplinary medieval studies and to the broader disciple of art history? The conference was not intended to be programmatic or prescriptive in offering settled answers to these questions, but instead to allow for an exploration of different possibilities. Nevertheless, a couple of trends emerged from the papers and from the lively discussions, and I want to focus on these two sets of issues here.

1) Close Looking and/or Critical Distance:

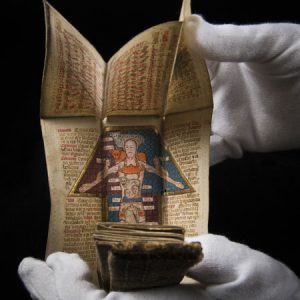

One vision for a newly “disciplined” medieval art history that emerged from the conference is characterized by a renewed emphasis on “close looking;” that is, on the intensive, ideally first-hand, visual and tactile engagement with individual works of art. This was most obvious in Herbert Kessler’s keynote address “Medieval Modern: Art in Time,” which featured his up-close investigation of the well-known reliquary box from the Sancta Sanctorum. It also appeared in Jennifer and Karen’s presentation on the physician’s almanac, during which reproductions of this complexly folded compendium of medical materials were passed around the audience to allow us to understand its structure by manipulating it; in Ludovico Greymonat’s presentation “From Pages to Walls: Designing a Painted Space in 13th-Century Salzburg,” which likewise featured a reproduction of a preparatory drawing for a series of wall paintings that was passed through the audience for our close investigation; in Sarah Guérin’s paper “Facing Facture and Pygmalion’s Dilemma,” which considered how Parisian ivory carvers worked with the specific qualities of ivory as a medium (no ivories were passed around); and in other contributions.

While these individual acts of close-looking were compelling, concerns about close-looking as a model for art-historical inquiry were expressed in discussion on both days of the conference. First, voiced by Jeffrey Hamburger in particular, came a concern that this type of intensive engagement with the work of art can close out engagement with the social and the political–with the workings of power in the Middle Ages. In coming so close to our objects we may be in danger of losing our critical distance from our period of study. This is not necessarily the case: Jennifer and Karen’s presentation, for example, identified the complex workings of the almanac as constructing the physician’s authority in relationship to his patient. Close engagement with a singular object could and maybe should eventually lead one to considering larger social and political questions. However, in practice this would likely strain the limits of time in a 20-minute conference talk, of space in a journal article, of an audience’s attention to either, and of a scholar’s interest and expertise. Is someone trained in doing this kind of intensive investigation also going to be expert in those larger issues and concerns? Is someone who is so close to the art objects and thus subject to their aesthetic appeal also going to be interested in engaging with the “ugly” aspects of the medieval past?

Secondly, concerns were raised about close-looking and issues of access and elitism. Kessler was able to view and to handle the Sancta Sanctorum reliquary box: how many of us would be allowed to do so? When Jennifer raised that question to him, his response was to emphasize advocating for greater access for more scholars to their materials. But that answer is not entirely adequate; for first-hand access to the materials also requires time and money for travel that are often hard to come by, especially for graduate students and junior scholars, as well as those of us working at institutions in more remote locations and with fewer resources, and those of us who have other professional and personal commitments (heavy teaching loads, increasing administrative burdens, family responsibilities, etc). One advantage of the more interdisciplinary model of scholarship that does not focus on intensive first-hand engagement with the work of art is that it is do-able from almost anywhere, any college town where the campus library has an active ILL office. To tie these concerns with close looking together, our physical distance as American scholars of a European past may be valuable as producing our critical distance from that past–we are not so in danger of falling in love with our art objects since we don’t see them as often–and the more open and democratic practices of interdisciplinary scholarship may likewise be valuable as promoting attention to the workings of power. I would not want us to turn our backs on these positive aspects of our existing practice.

2) Historiography and/as Disciplinary Self-Reflection

A second emphasis that emerged from the papers and the discussion was on historiography. The papers in the session “Periodizations Past and Present” in particular focused attention on the modern construction of the categories under which we consider medieval art objects, on the inevitable weaknesses of any and all such systems of categorization, and yet on our need for some way making the materials meaningful for ourselves and our students. And Christopher Lakey’s paper “Post-Formalism and the Photographic Mediation of Medieval Sculpture” focused on the crucial role of photography in the history of medieval art history. In his formal response to the conference papers Hamburger emphasized historiography as a way of shaping the future of the field, for example finding in early-20th century medievalist scholars’ engagement with modernism the motivation for a renewed engagement with contemporary art. And in the final discussion he pointed to historiography as a source for a self-critical re-engagement with older concepts such as style. In this way, he highlighted engagement with historiography as a means for preventing a new turn to disciplinary art-historical issues from being a simple return to field’s past. It is important, however, to specify what this kind of historiographic work would need to look like; not a cataloging of past scholarly errors that have been triumphantly overcome by the present work (as in a typical literature review), but something that takes the field’s past texts and museum practices seriously for the lessons they have for our work in the present and future.

The importance of critical self-reflection as part of a newly “disciplined” practice in the field was emphasized in a number of papers, in particular in Alexa Sand’s “Interdisciplinary Objects: Thick Description and the Manuscript Studies Paradigm,” and Allie Terry-Fritsch’s “Medieval Bodies, Medieval Minds: Somaesthetics and Viewing Bodies in the Expanded Field of Art History.” However, I sensed a hesitance to engage with another potential source for critical self-reflection in our work: theory. Kumler in her introduction mentioned new theoretical positions such as the new materialism and object-oriented ontology that have the potential of bringing new questions to bear on our objects and so providing a way for a renewed engagement with the work of art to be something other than a return to old models of disciplinary practice. And yet even the papers in the session on “Objects, Agency, and Efficacy,” which seemed most suited to these new theoretical positions, refrained from directly engaging with them. Feminism was mentioned positively at several points; by Hamburger, for example, as a discourse on agency that could help problematize the ascription of agency to art objects. While I agree that historiographic work is important as promoting self-reflective acts of scholarship, it may also promote a bit of navel-gazing: art history about art history and art-historians! Theory, too, is a resource that we should not turn away from.

In closing, I want to echo the comments made by Jeffrey Hamburger and Avinoam Shalem in introducing their formal responses at the end of the conference, by stating that whatever criticisms I have raised here are not meant to detract from what was presented but to encourage on-going discussion and debate. This conference was one of the most inspiring events I have attended in my career. If it points the way to the future of our field, then we are turning in a positive direction.