Counter-Productivity Break-Out Groups

The year marked the fourth BABEL Working Group Conference, held at the Centre for Medieval Studies, University of Toronto. This was, by many accounts, the best yet. While attendance was reportedly higher than last year’s meeting at the University of California, Santa Barbara, the conference felt smaller, more manageable, and more intimate (as the “yearbook” photos by Sara Akbari attest). This was in part due to the close proximity of the various venues, as well as to the slightly more generous scheduling of breaks. The rooms were good, the tech worked very well (as far as we saw, and we, as art historians, are picky about this), and the buns! The buns were delicious.

The tweeters provided excellent, on-the-fly summaries and commentaries, which have been storified by Jonathan Hsy here: Day 1, Day 2, Day 3, and miscellaneous other. We therefore won’t attempt to sum up the whole, vibrant event. Instead, we’ll give a few general reflections, and then will focus on The Material Collective’s session.

The conference theme, “Off the Books,” was taken in several ways throughout the weekend. The opening plenary session set the tone well. Alex Gillespie’s plenary started us off by showing some ugly books. She repeated a dismissive comment someone made to her: “Why didn’t you just talk about manuscripts the way we expected you to?” In a way, this was a weekend of people not talking about books they way we are generally expected to. There were songs, spoken-word poetry, personal narratives, calls to question not only methodologies, but also the ways that we assess them. Alex set us all off in a direction of exploding expectations: that all mss are precious and beautiful things, that the proper reaction is often marveling at them.

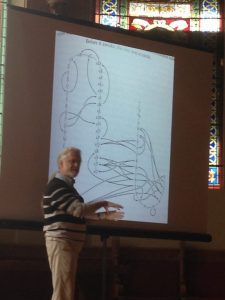

Randall McLeod’s mad-crazy diagrams

.Randall McLeod followed this by showing us ghost books, blind printing that, while nearly invisible, can be reconstructed with raking light and, it seems, a lot of squinting. He hunted for fragments of texts across pages, quires, books, and time, producing diagrams with visual complexity approaching that of medieval Islamic calligraphy These ghost books, he argued, are in conversation with one another, and with the more visible books they haunt.

Finally, the session argued for a welcome effort to breaking down distinctions between scholarship and other kinds of creative endeavor. Whitney Anne Trettien’s plenary talk on the combination of book history and book making in her work explored the productive tensions between what we do in our more official capacities, the work that makes it into job letters and tenure files, and the other things we do that might well seem to us just as important and interesting. She grappled with whether or not her acts of making will “count” for her in any way; she seemed to worry over that, but not want to worry over it, and not let it stop her from doing it.

In these three talks, then, we had ignored books, studied them the “wrong” way, lost books that never quite existed but which call out for our attention, and were introduced to new books that press us to rethink the old books we study and the methods we bring to them. These were themes that were echoed in several of the sessions that we attended, as well as our own.

In advance of our session, “Counter-Productivity: Valuing Scholarly Processes,” we circulated a simple 5-question survey:

- What do you actually do when reading for a research project? When you get to the library, archive, museum, or other site of research and encounter the manuscripts, collections of papers, works of art, or other materials that you have come to see?

- What do you do when you are thinking?

- What do you do when you sit down to write?

- What do you find yourself doing instead when you are meant to be doing any of these things?

- How and why did you develop your own scholarly practices? Have your practices as a scholar shifted over time and if so how and why?

Based on the results, we are a bunch of highly caffeinated, drunken gym rats who spend a fair amount of time on Facebook (er, maybe I’m just writing autobiography now?), but we are also writers who like some solitude (or noisy chaos), people who need to write daily, or to set aside special times for writing, or write anytime, or write only when the inspiration strikes, or only when the deadline approaches (or passes). In short, “we” don’t have a single, field-approved writing process. And yet, we write. And, on the whole, love to do so. (The session seemed to have a lot of overlap with the new How We Write, edited by Suzanne Conklin Akbari, and the volume was invoked several times throughout the conference. Get a copy!)

The session itself was very well attended; better than we had anticipated, in fact, which suggests that we has hit a nerve with the conference participants. We began with five brief presentations: Marla Segol gave us her “rules” for working in the reading room (bring a sweater) and Lara Farina gave us some “counter-productive” advice; Brendan Sullivan, Mary-Kate Hurley, and Marian Bleeke each spoke of writing and its way of entangling the personal with the professional, the scholarly with the affective. Brendan spoke of needing to “work out what made this work matter to me to begin with.” Mary-Kate advised us “to be gentle with process.” And Marian, though in the room with us, presented a video of her writing process:

Next we broke into small groups in order to involve everyone in the discussion, which was still going on when we had to call time. Actually, like the best discussions, it was still going on well after “class” had ended, but we decided we’d better call it a day so that the next group could have the room.

The grand impresario of the whole, grand affair, and of the larger project that is the BABEL Working group, which in turn spawned The Material Collective, tackled the notion of work that is off the books in her characteristic way, idiosyncratically passionate and lyrical. Her talk was called “Illegitimate,” a subject she has written about previously (here and here). In it, she importuned us — as representatives of our field and profession, to have the courage to step outside of standard modes and practice:

So, thank you to all of the wonderful monsters in the Academy of Thought, friends old and new, collaborators past, present, and future. See you at the next BABEL, online, in tables of contents, and in the wider public sphere, which we call into existence each time we speak.