Martha Easton • Bryn Mawr College

Recommended citation: Martha Easton, “Was It Good for You, Too? Medieval Erotic Art and its Audiences,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 1 (2008). https://doi.org/10.61302/BUIO3522.

One challenge of analyzing visual imagery using language is that the cultural filter of language itself inevitably nuances and reinterprets our initial nonverbal experience: applying words to images, we contextualize them, giving them shape, history, and meaning. Especially when the images in question have sexual content, the words selected to describe them can affect the way they are perceived: the same visual material might be deemed suggestive, titillating, erotic, pornographic, or obscene – and each word choice connotes, and at times perhaps promotes, a world of cultural and even physical response. There is really no word that is completely neutral to describe this imagery – even the word “sexual” itself suggests associations that may or may not be accurate.

When I selected my title for this article and for the conference paper from which it was derived, I was deliberately attempting to entice, and yes, titillate, my potential audience. My use of the word “erotic” to describe these images is also deliberate, as I am attempting to avoid what I see as the relativistic moral and judgmental potentialities of words such as ‘obscene’ and ‘pornographic,’ even as I acknowledge that the choice of ‘erotic’ has its own connotations of intentional sexual stimulation. This leads me to my larger point — when we give meaning to images using words, exactly whose meaning is privileged? And further, when we allow images no words at all, what happens to them? Because of the traditional tendency of historians of medieval art to focus on religious imagery and monuments, secular objects become marginalized and secondary; in the case of the erotic images found in medieval art, they disappear, do not become part of the canon, and become all but eliminated from serious scholarship. Imagery that is sexual in nature, in either religious or secular contexts, becomes invisible to us.

In spite of the prevalence of sexual imagery in medieval art, both religious and secular, a misconception predominates, certainly in the general public and to some extent even among scholars, that Christian morality perhaps prudishly constrained medieval people. However, it is clear from even a cursory look through medieval writings as diverse as legal proceedings, penitentials, sermons, medical treatises, literature, fabliaux, and poetry, that medieval people themselves were very interested in the topic of sex. When sex and sexuality have in fact been examined, it has tended to be by scholars of history, literature, or medicine rather than art. The sexual image has received much less attention; the image has been divided from the word. Ironically, the category of ostensibly religious art contains the most explicitly sexualized images. It is perhaps the modern tendency to separate the sacred and the sexual in fact that has censored this material.

My project here then is to examine some of these lesser-known medieval images, and to think about how they might have been characterized as erotic, while understanding that the category of the erotic is neither absolute nor ahistorical. But I am also interested in exploring how the potentially erotic nature of such images makes viewers respond to them, not only at the time they were produced, but in later times as well. This historiography of the reception of medieval erotic images suggests that our history of medieval art is a constructed one, based on the intellectual, religious, and perhaps even moral predilections of the historians themselves. With the advent of newer methodologies such as feminism and queer theory, an increasing interest in medieval sexualities and sexual imagery in art is perhaps thwarted by a lack of available existing foundational research because of the virtual elimination of such topics and objects from scholarly consideration in the past. Despite these challenges, scholars have begun the project of unraveling the visual codes of eroticism in medieval art. The triangulation model, as formulated by Madeline Caviness, provides one method for understanding how sexual imagery in medieval art might be understood and theorized. With the current interest in research on sex and sexualities, motivated in large part by theory, scholars have been motivated to look at the way sexuality has been historically constructed in the past in order to understand the way it can be understood in the present.

The definition of the erotic in medieval art is complex and even contradictory. Some visual images that could be seen as sexualized or erotic, when seen through the lens of medieval culture and religious thought could also have a more spiritual interpretation. Scholars of medieval mysticism also struggle with how to understand mystical language and practices which appear profoundly sexual in nature; it is often ambiguous whether a verbal and pictorial emphasis on the carnal is metaphorical or actual, referring to spiritual or physical experience, or some elision between the two.[1] Particularly in the later Middle Ages when the devotion to the passion of Christ reached its height, and the emphasis on Christ as a bleeding, suffering, fully human being was evident in both visual and verbal culture, mystics often described a union with a beloved Christ in extremely physical terms. Especially women, but men too, described ecstatic experiences in which they nursed from Christ’s sidewound as if it was a breast, or felt themselves penetrated by Christ, or so lost themselves in mystical adoration and abandonment that they experienced physical shuddering that seem most akin to orgasm. In general, late medieval piety is wrapped up in the body in a way that often seems startling and even distasteful to the modern reader. The question is, how are we to interpret such experiences? Some would suggest that these are the Freudian yearnings of those who have often suppressed more typical human sexual experiences because of religious beliefs and practices. Others would argue that it is incorrect to assume that modern and medieval understandings of sexuality necessarily coincide; that in fact we must allow for an alterity to medieval people that allows phenomena of a deeply physical nature to be seen as spiritual. And still others would argue that it is possible that these types of experiences can be both religious and sexual, even erotic.

While scholars concerned with medieval mysticism have engaged with the problem of the interpretation of the eroticized language of seemingly religious experience, fewer scholars have attempted to grapple with the meaning of potentially sexual or erotic imagery in medieval art, especially images that appear in religious contexts. Two scholars who have engaged with the meaning of seemingly sexualized images were Caroline Walker Bynum and Leo Steinberg; later scholars have commented on their famously acrimonious debate.[2] In response to Steinberg’s assertion that medieval and Renaissance images emphasizing the genitals of Christ focus on his sexuality as evidence of his full humanity, Bynum countered that we should not assume that medieval people viewed breasts and genitals in the same sexualized way as we do. Instead, she argued that in the Middle Ages Christ’s body in all its physicality could connote nourishment, suffering, and salvation, but never sex. Despite their differences, in the end both Steinberg and Bynum rely on theology to explain the exposed body of Christ. In contrast, scholars such as Karma Lochrie, Robert Mills, and Richard Trexler have opened up the possibilities for sexual and homosexual responses to this kind of imagery.[3] Lochrie especially is interested in the ‘queering’ of texts and images in order to upend traditional scholarship that views mystical experience through a heteronormative lens, even if it means some gymnastic readjustment of gender construction.[4] Lochrie has been particularly concerned with the way medieval female mystical experience has been characterized by modern scholars; for example, the feminization of Christ’s body is an established feature of late medieval piety, but the adoration of this body by female mystics is always described by Bynum and others following her lead employing either heterosexual or asexual models. Similarly, Mills and Trexler explore mystic male responses to the body of Christ and the possibilities that they might be characterized as sexual, even homoerotic, as well as spiritual. We might say that the definition of ‘erotic,’ then, is akin to the definition of pornographic – it is at least in part a matter of position. We need to think about for whom a behavior, or especially for us an image, might be characterized as erotic—for a man or a woman, for an artist, patron or viewer, for a medieval or modern person. And we should also ask ourselves if those categories are necessarily at odds with each other.

Some medieval images that are ostensibly religious show encounters that may appear suggestive, such as illustrations of the Sponsus and Sponsa from the Song of Songs.[5] The erotic language of the biblical text informs images of these figures kissing or embracing, and the fact that the Bridegroom and the Bride are usually interpreted as Christ and the personified Church, and the Church further identified as the Virgin Mary, lends these images complicated and even incestuous overtones. The question of interpretation remains; are these to be seen solely as symbolic and exegetical, or are other meanings possible with such freighted imagery?[6]

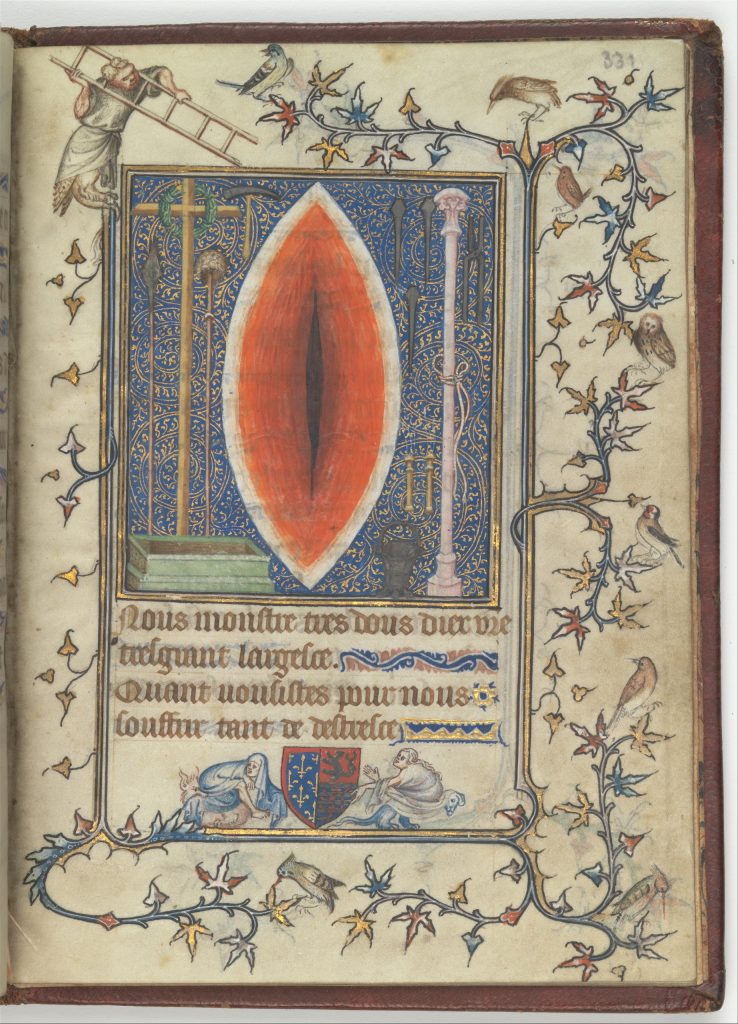

Fig. 1. Wound of Christ, Psalter and prayer book of Bonne of Luxembourg, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cloisters Collection, MS 69.86, fol. 331r.

The same question can be asked of the isolated and vertical side-wounds of Christ, which become popular in fourteenth-century Books of Hours (Fig. 1). I have suggested elsewhere that these images might be multivalent and connote sexuality as well as religion, inspiring responses beyond the theological.[7] Specifically, I argue that the wound of Christ might be a vaginal image, especially for a viewer encountering such a sight in the private space of a manuscript. Certainly the image of the wound of Christ is in fact deeply informed by religion as the site of Christ’s suffering and sacrifice, the source of Eucharistic blood, and the inspiration for mystical conflations of wound and breast, informed by medical beliefs about the interconnectedness of blood and milk.[8] The shape of the wound can be seen as mandorla-like, but it is also visually identical to the way the vagina was depicted in places such as medical manuals, as well as the type of sculpture called the sheela-na-gig, to be discussed below. The wound is also an entrance into and exit from the body, the devotional contemplation of which led to a kind of swallowing and engulfing, allencompassing experience, the liminal zone from which the Church is literally born, the inversion of the Satanic hell mouth.[9] A folio leaf from a fourteenth-century Flemish Book of Hours (Fig. 2)[10] includes a phrase from the text of the Psalms, “I said in the midst of my days I shall go to the gates of Hell,” as well as an image in the bas-de-page of a man being led to bed by a woman; the “hell mouth” is both the entrance to the bedchamber and to the body of the woman herself, the woman as the gates of hell an analogy made by writers from Tertullian to Boccaccio.[11] But here the gates of hell do not seem particularly threatening, the man seemingly a willing participant in his damnation.

Fig. 2. “Gates of Hell,” Book of Hours, Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Douce 6, fol. 160v.

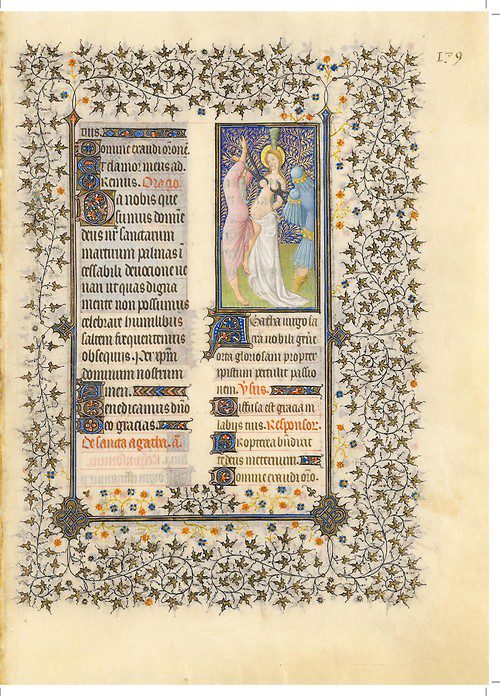

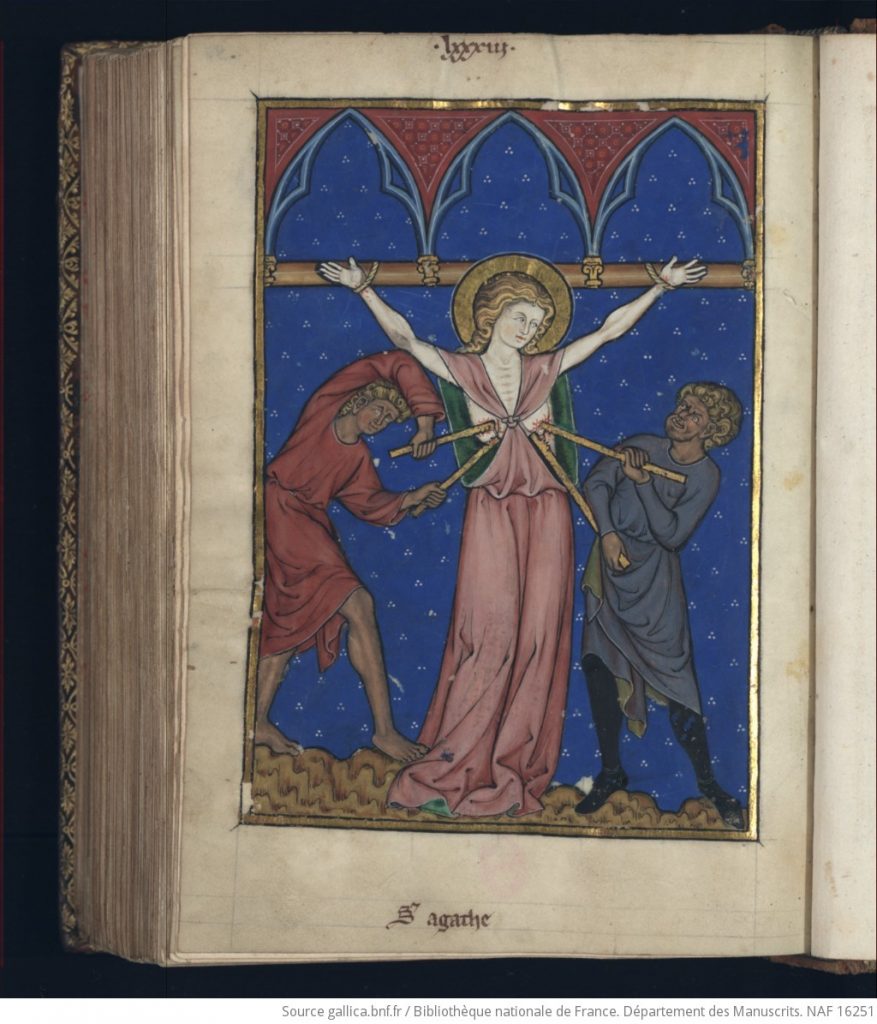

The idea of woman as pathway to temptation and sin is of course derived from Genesis and the story of the Fall, and the nude body of Eve suggests the source of the sin. In fact, nudity is much more likely to be found in religious rather than secular imagery in the Middle Ages, but it can be confusingly coded. Adam and Eve are represented nude in their prelapsarian state of innocence; in some earlier medieval images, their bodies are often barely distinguishable.[12] It is only after the fall that their nakedness becomes shameful. Images of the Last Judgment often explicitly contrast the blessed, fully robed and resplendent in heaven, with the damned, writhing in their nakedness much as they did in the sexual sins that condemned them to hell. But virgin martyrs such as Agatha and Barbara were often represented partially or fully nude; especially in the later Middle Ages they are depicted as the visual embodiments of the ideal women described in love poetry and romances, with their long blonde hair, fair complexions, swelling bellies, and high, apple-like breasts (Fig. 3).[13] Such images may provoke both religious and erotic responses in viewers, both medieval and modern. The paradoxical nature of these images of virgin martyrs ostensibly created for religious contemplation, but depicted half or fully nude, often in the throes of their torture, means that a singular visual response to them is unlikely. Margaret R. Miles used the term “religious pornography” to refer to such images; Madeline Caviness has used the phrase “sadoerotic.”[14] Many of the images of the tortures of the virgins depict them with bare breasts; here the breast becomes a multivalent symbol of motherhood, femininity, and erotic longing–in the Golden Legend Agatha herself connects her breasts with all these functions, chastising her thwarted suitor for removing “that with which your mother suckled you,” but also bemoaning to St. Peter “since I am so cruelly mangled no one could possibly desire me.”[15] Agatha’s words suggest that sight affects desire, that eroticized looking, or scopophilia, is wrapped up with the image of the disempowered and fetishized woman.[16]

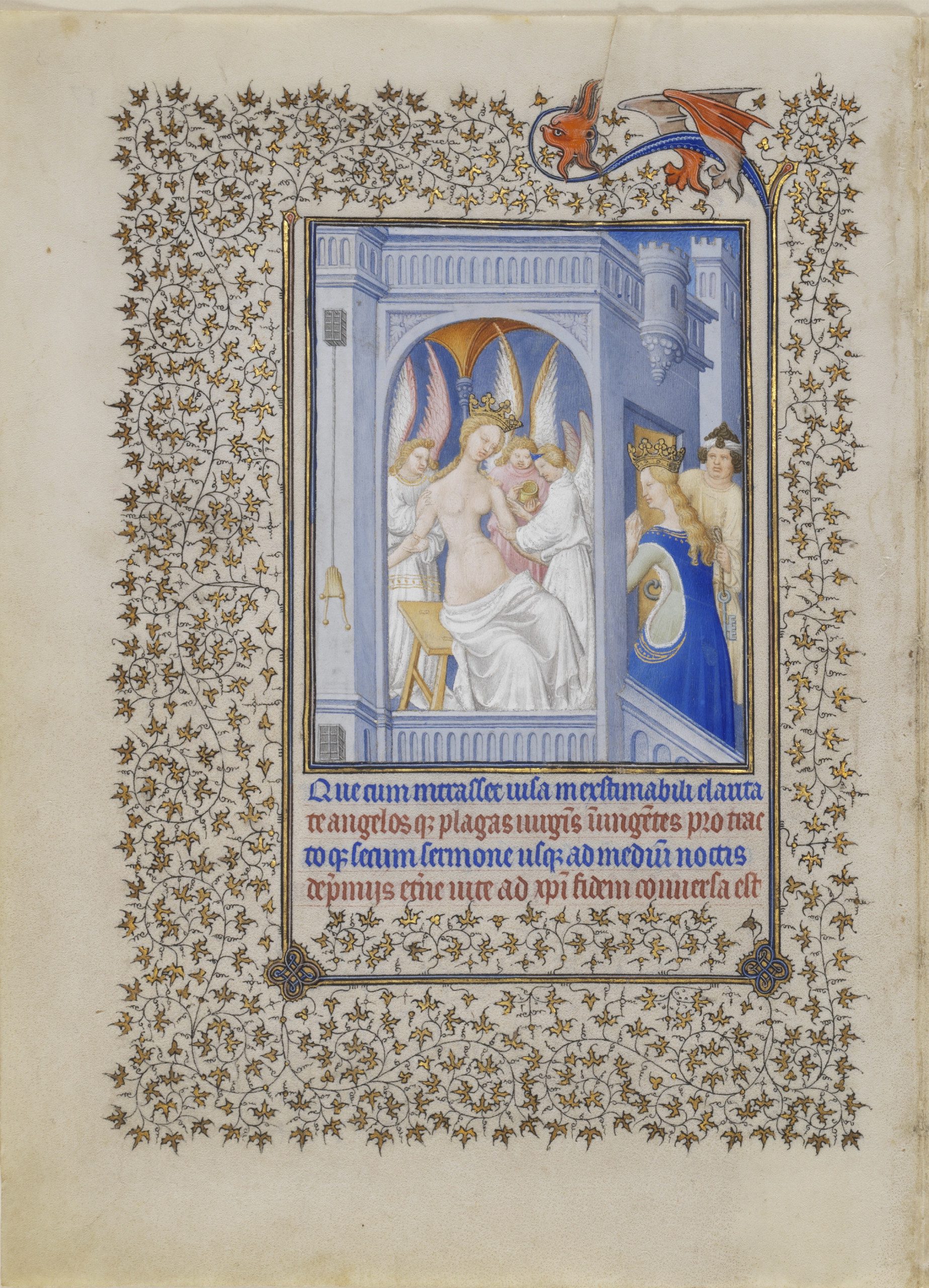

Fig. 3. Limbourg Brothers, Torture of St. Agatha, The Belles Heures of Jean, Duke of Berry, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cloisters Collection, MS 54.1.1, fol. 179r.

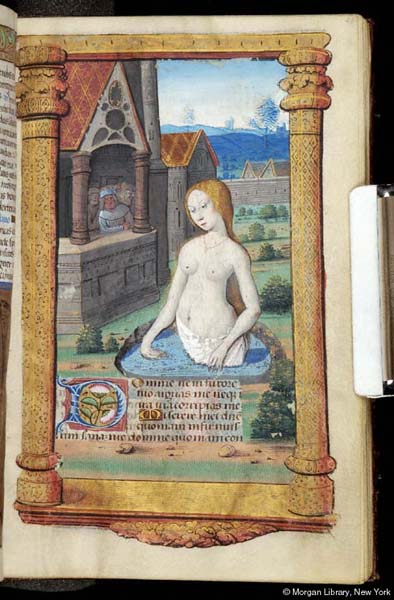

There is something about seeing, (as opposed to reading), which changes the nature of perception. The implications of the gaze, and specifically the gendered gaze, were addressed in the Middle Ages; in his famous treatise on the art of courtly love, Andreas Capellanus maintained that desire resided in sight, that it was created from the “inborn suffering” produced from looking at the opposite sex.[17] The many images of David gazing on the undraped form of Bathsheba, often illustrating the historiated initials of the Beatus pages of thirteenth-century Psalters, as well as later Books of Hours (Fig. 4), aptly illustrate this idea, and further complicate the gaze of the viewer on undressed female saints.[18] In Books of Hours, the image of David staring at Bathsheba in her bath most often accompanies the Penitential Psalms, and the image in conjunction with the text therefore alludes to the rest of the story—David will impregnate Bathsheba and then send Uriah, Bathsheba’s husband, off to war where he will ultimately be killed, freeing Bathsheba to marry David. Although the text of the Penitential Psalms obviously has to do with David’s later regret for his sinful actions, these images freeze Bathsheba, she of the white skin, round breasts, swelling belly, and veritable explosion of fertile foliage at her groin, freeze her at a time long before regret has set in, when David looks at her with desire and longing, as does, perhaps, the viewer outside the frame. In contrast to the biblical account, Bathsheba often gives a complicit look back.

Fig. 4. David and Bathsheba, Book of Hours, France, perhaps Tours, ca. 1500. New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, MS M. 12, fol. 41r.

Fig. 5. The Fall, The Très Riches Heures of Jean, Duke of Berry, Chantilly, Musée Condé, fol. 25v.

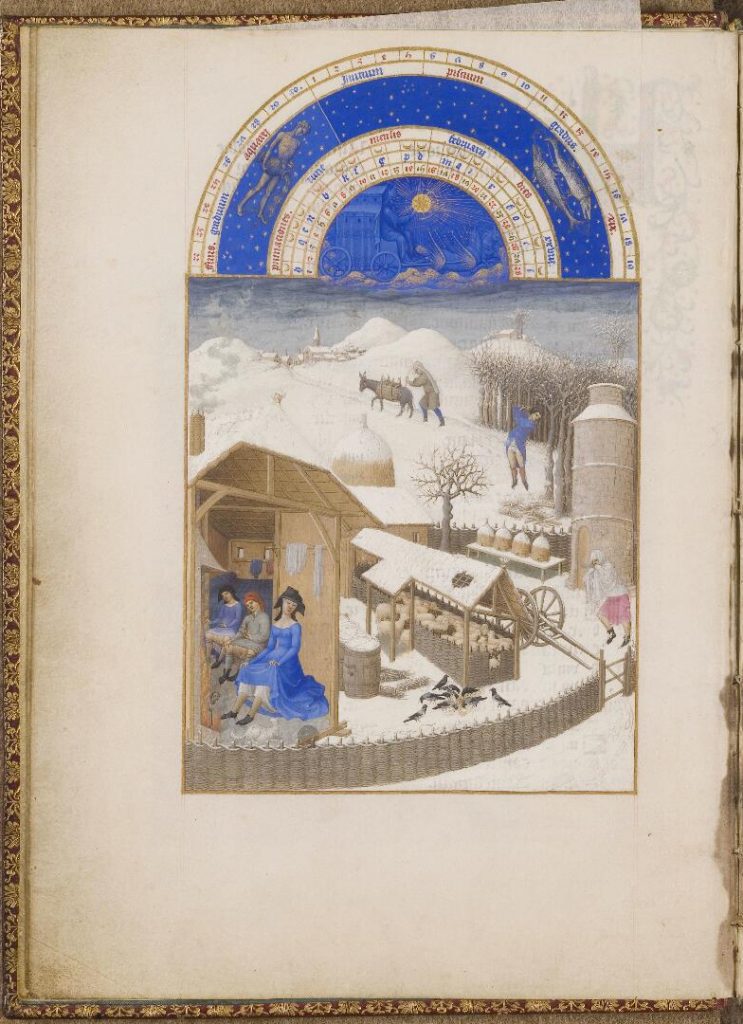

Fig. 6. February calendar page, The Très Riches Heures of Jean, Duke of Berry, Chantilly, Musée Condé, fol 2r.

Fig. 7. August calendar page, The Très Riches Heures of Jean, Duke of Berry, Chantilly, Musée Condé, fol. 8v.

Some of the most visually alluring images of women produced during the later Middle Ages were made by the Limbourg Brothers in the manuscripts they produced for Jean, the Duke of Berry. The famous image of the Fall in the early fifteenth-century Très Riches Heures depicts the story in a cyclical continuous narrative, with Eve clearly responsible for the chain of events leading to the Expulsion from Paradise (Fig. 5).[19] Her complicity with the Devil is securely coded with the representation of the serpent with a female head;[20] her sharing of the fruit with Adam is more an act of aggression than temptation as she looms over him and he cowers beneath her, wielding off her advances. Do we assume that such images of a luscious, blonde-haired and apple-breasted Eve connoted the evils of women to the medieval viewer? Did Jean de Berry avert his eyes, or did he allow himself the pleasure of perusing Eve’s naked form?[21] Did he perhaps imagine the courtly ladies depicted in the calendar pages of the same manuscript, so similar to Eve in face and body, in a similar state of undress? In this manuscript in particular, nudity seems to connote class distinctions.[22] In the calendar page for February (Fig. 6),[23] peasants rest by the fire and lift their clothing, exposing their genitals. In the August page (Fig. 7),[24] naked peasants cool off in a stream, while in the foreground voluminously dressed aristocrats ride by on their horses. Yet again, the position of the aristocratic women dressed in black mimics the naked peasant just above her, and her tight bodice and the drapery folds caught between her legs emphasize her breasts, belly, and groin.[25]

Fig. 8. Limbourg Brothers, Catherine in Prison, The Belles Heures of Jean, Duke of Berry, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cloisters Collection, MS 54.1.1, fol. 17v.

Breasts, belly, and groin are on display again in the image of Saint Catherine in prison, from the Duke of Berry’s Belles Heures (Fig. 8). According to the Golden Legend, the articulate and persuasive Catherine converts the followers of the Roman emperor Maxentius (including his wife) while in prison awaiting her final tortures and death.[26] Yet the emphasis in the textual narrative on Catherine’s assertive powers of speech seems completely undone by the passive display of her undraped body, a display that is mentioned nowhere in the text.[27] It must have taken an unusually resistant viewer to think only of the religious and sacrificial significance of Saint Catherine, to see her nearly nude body as nothing more than pure and virginal, an offering to God. Particularly because here text diverges from image, and there is no textual basis for depicting Catherine unclothed in jail, it suggests that scopophilia is operating here whether it is conscious or unconscious, whether on the part of artist or patron.

Fig. 9. Limbourg Brothers, Temptation of a Christian, The Belles Heures of Jean, Duke of Berry, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cloisters Collection, MS 54.1.1, fol. 191r.

Because the story of Catherine mimicked that of so many other virgin martyrs in that it is their sexual rejection of a pagan man, and not so much their Christian beliefs, that leads to their martyrdom, the erotic element is present in their stories in a way that is almost unheard of for male martyrs.[28] Much like the comparable images of Eve and the aristocratic women in the calendar pages of Très Riches Heures, Catherine’s body in the Belles Heures is similar in appearance to the woman who is shown tempting a Christian while Saint Paul watches, on folio 191 of the same manuscript. In the latter remarkable image, the temptress actually reaches under the robe and moves up the thigh of the reclining man (Fig. 9).[29] Yet paradoxically in the Belles Heures it is the virgin martyrs, and not the temptress, who is depicted nude. In these two manuscripts, illuminated by the same artists for the same patron, there seems to be some ambiguity surrounding the clothed and exposed human form. The temptress of the poor Christian is clothed, in the same manner as the aristocrats populating the calendar, and the world, of Jean de Berry. Adam and Eve are nude, peasants are sometimes partially or entirely nude, but so are the virgin martyrs such as Catherine and Agatha. Nudity in these cases seems to have a variety of potential, even contradictory, meanings. Similarly, there can be complicated viewer responses to the often-eroticized images of Mary Magdalene and Mary of Egypt,[30] who are covered with miraculous growths of hair during their long sojourns in the desert, but which in effect reveal more than they conceal. According to their legends, these miraculous occurrences were to protect their modesty when unexpectedly confronted with men, but these late medieval images, like Catherine’s nudity in the Belles Heures, undo the significance of the miracles and render the women perpetually open to the gaze. Gregor Erhart’s famous sculpture of Mary Magdalene, now in the Louvre, conceals almost nothing, with the saint’s wavy dark locks coursing down her pale, voluptuous body (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10. Gregor Erhart, Mary Magdalene (La Belle Allemande), Paris, Musée du Louvre.

Fig. 11. Tillman Riemenschneider, The Assumption of Mary Magdelen, 1490-192, Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Munich.

Tilman Riemenschneider’s version has an even more striking approach to the hirsutism of Mary Magdalene; her pubic hair-like tufts of hair completely cover the saint’s body, leaving her breasts exposed, and are clearly separate from the lengthy strands flowing from her head. Here Mary Magdalene most closely resembles images of the wild men and women, part of the monstrous races believed to exist on the edges of civilization, and associated with sexual excess (Fig. 11).[31]

If we see the exposed breasts of the virgin martyrs as ambivalent in their effect on the viewer, connoting both purity and sexuality, eliciting a potent visual response of piety, empathy, and desire, what about the exposed breasts of the Virgin Mary herself?

Fig. 12. Jean Fouquet, Melun Diptych (left panel), Berlin, Staatliche Museen, Gemäldegalerie, Inv. 1617.

Fig. 13. Jean Fouquet, Melun Diptych (right panel), Anvers, Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Inv. 132.

Bynum and other scholars see images of the breastfeeding Virgin in almost exclusively religious terms, as symbolic of the spiritual nourishment offered the faithful viewer, the Christ Child turning his gaze on the viewer in order to invite them to partake in the sacred sustenance.[32] Miles also connects Italian examples to fourteenth-century anxieties about the food supply in the face of famine and the controversy over the practice of wet-nursing.[33] Most modern scholars writing about images of the nursing Virgin seem to resist connecting the display of the breast to erotic desire, although the polished white breasts of Jean Fouquet’s Virgin in the Melun Diptych, with Etienne Chevalier and his patron saint looking on in the adjacent space, seem to thwart the connection with food in their practically nipple-less, fetishized appearance (Figs. 12 and 13).[34] The chain of gazes only enhances this effect – the Christ Child does not look at the viewer, while Saint Stephen seems to look quite pointedly at the buxom breast that has seemingly burst forth from the confines of the Virgin’s blue dress; she herself looks down upon it with an air of cool self-appraisal. Perhaps because this image of the Virgin is so problematic, with a further layer of complication in that it is said to be an image of Agnes Sorel, the king’s mistress, the Melun Diptych is typically ignored in discussions about the meaning of the breast-feeding Virgin.

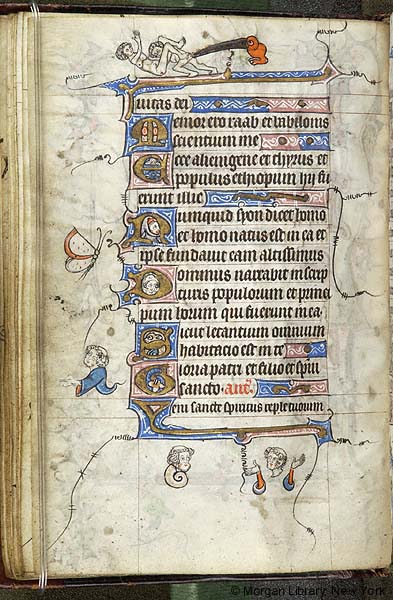

The prevalence of the image of the Virgin with an exposed breast in the Middle Ages, however we interpret it, suggests that this kind of image was meaningful to its contemporary audience. We might contrast this with the uproar that greeted Chris Ofili’s version, exhibited in 1999 in the aptly-named “Sensation!” show at the Brooklyn Museum of Art.[35] Mayor Rudy Guiliani’s attempts to shut down the show, and ultimately the museum itself, because of the sacrilegiously bare-breasted Virgin, were unsuccessful, but the painting was put under guard for the duration of the exhibition. Because most of Ofili’s detractors did not actually visit the show, they failed to notice or mention the cutouts from pornographic magazines that float around the Virgin, focusing their attention instead on the Virgin’s bare breast and the fact that it was fashioned out of elephant dung (a sacred substance in Ofilii’s ancestral homeland in Africa.)[36] Paradoxically, it seems that the most sexually explicit images are found in religious spaces like churches, cathedrals, and devotional manuscripts, and depending on the context, can be read as censorious rather than celebratory of eroticism and love. The pairs of same-sex lovers in one of the early-thirteenth-century moralized Bibles appear in conjunction with God’s banishment of Adam and Eve as well as a moralizing text.[37] Naked couples, both hetero- and homosexual, grimace and grind on the corbels of medieval churches.[38] Misericords, the carvings found underneath choir stall seats, are a major source for a wide variety of salacious themes[39] – pairs of lovers; bare-breasted sirens and mermaids; men exposing their buttocks and genitals;[40] naked women astride animals. What many of these images have in common is that they appear in the margins, outside the frame; in Camille’s words, “on the edge.”[41] These spaces seem to be areas in which the proper order of things is reversed, the world is turned upside down,[42] and the transgressive may be depicted, perhaps in order to render it powerless, perhaps to harness its power as protective, much like the numerous badges that have been found with disembodied, sometimes winged, male and female genitalia.[43] Yet some of the most graphic marginal imagery may have other functions; Paula Gerson and Michael Camille have speculated that the image of a naked couple seeming either to copulate or engage in oral sex in the top margin of a late medieval Book of Hours to be [is] a reference to a biblical phrase on the same folio (Fig. 14).[44] Gerson has argued that the artist must have been literate in order to create the resulting visual puns, and she also suggested that the patron/owner, very likely a woman, must have had some hand in the selection of the often-sexualized marginal imagery in the manuscript. This example of a blatantly sexual image in the margins of a sacred text is by no means unique, and many of them cannot be tied to the text in the same way.

Fig. 14. Naked couple, Book of Hours, New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, MS M. 754, fol. 16v.

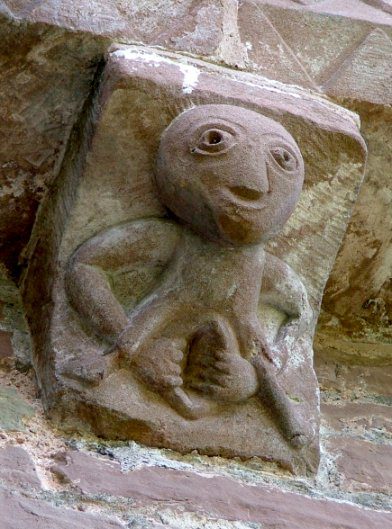

The study of sheela-na-gigs presents a particularly interesting evolution of the changing perception/reception of medieval objects that do not fit into a pattern of expected/accepted iconography. Sheela-na-gigs, sculpted images of hag-like female figures squatting and pulling back the lips of their vaginas, inhabit the exterior of many Romanesque churches, especially in the British Isles. Their precise dating is uncertain, but they seem to begin to appear in the twelfth century. Nineteenth-century antiquarians often described these objects with disgust and alarm; not only was their sense of propriety and personal code of morality offended by these images, but in a reverse of the Mulveian “male gaze” which posits that representations of women are generally passively subject to a penetrating patriarchal look, these men seemed to feel threatened and even assaulted by the sight of the sheelas.[45] Perhaps in order to regain control of their viewing experience, to restore (reinstate) the male gaze, antiquarian drawings of the sheelas often do not simply reproduce them, but rather alter them, so they seem to become more visually appealing, more arousing, more, shall we say, erotic. Some close their eyes and appear to be masturbating – no surviving sculptures match these drawings. The relative paucity of scholarship on the sheelas probably stems more from a feeling that prevailed until very recently that naked, vulva-exposing women were problematic and inappropriate, unworthy of serious attention and too difficult to explain rather than from a lack of awareness of their existence or lack of interest in their existence. It is perhaps this reluctance to view these figures within a Christian context that led many of the early sources on sheela-nagigs to connect them with Norse mythology or pagan fertility charms.[46]

In 1977 Jørgen Anderson published his book The Witch on the Wall: Medieval Erotic Sculpture in the British Isles,[47] and then in 1986 Anthony Weir and James Jerman published Images of Lust: Sexual Carvings on Medieval Churches; the titles of both works connect the sheelas with eroticism, lust, and sexuality. Since these two books, more scholars (although not many) have entered the discussion about sheela-na-gigs, and whether the authors connect the sheelas to pagan, pre-Christian fertility symbols, or Celtic and Irish texts and contexts, or other sculpted figures from the Continent in explicit sexual poses, most see the naked female body and exposed vagina functioning as a site of religious anxiety, connected to original sin, death, and decay. Thus many scholars concerned with sheela-na-gigs make the suggestion that they function in a way that is at least in part apotropaic; their placement near the doors and windows of churches and castles protect these liminal zones, these vulnerable entrances and exits, through a display of the female body’s most obvious liminal zone. Two recent articles by Eamonn Kelly and Patrick Ford discuss the sheela-na-gigs in this way; their presence in volumes with the words “obscenity” and “obscenities” in the titles lays a particular set of meanings over the images.[48] In fact, Ford explicitly states that sheela-na-gigs are “hardly erotic images, at least in the conventional sense of the word.”[49] These more recent scholars follow an older line of thinking, deeming the sheelas as obscene rather than erotic or even pornographic, and arguing that they were understood as such in their own time as well as ours.

Fig. 15. Sheela-na-gig, Kilpeck, Church of St. Mary and David.

In 1985, Nancy Spero created her well-known image of a colorful row of sheela-na-gigs in a kind of Rockettes’ kick-line.[50] For Spero and many feminist artists, the representation of the female body could never be fully reappropriated from patriarchal discourse and presented in a positive way; the female nude in particular was too freighted with art historical and ideological baggage. Instead, Spero selected an image of a nude female from history, and re-presented it in an attempt to point out and deconstruct patriarchal stereotypes. Yet in just the last few years, the sheela-na-gig has been somewhat reclaimed, particularly by feminists seeking to recover for the sheelas some kind of positive agency, especially as goddess images. Marian Bleeke suggests that at least to the unlearned audience of the community surrounding Kilpeck, the famous sheela there, seen in conjunction with other corbel sculptures on the church, might have connoted reproduction and birth, mirroring human experience (Fig. 15).[51] Barbara Freitag argues that sheelas combine the universals of birth and death with their skeletal heads and open fertile genitalia, and should be viewed in a context of folk and talismanic assistance in these life passages.[52] Catherine E. Karkov tells the story of the uproar when a female scholar was denied access to the sheela-na-gigs at the National Museum of Ireland;[53] a sheela has also recently served as the cover illustration for a feminist revisionist history of early medieval Ireland (Fig. 16).[54]

Fig. 16. Sheela-na-gig, County Cavan. Dublin, National Museum of Ireland.

Study of the sheela-na-gigs is complicated by the observation that many of them appear to have been partially recarved, particularly in the genital region. Even this type of intervention in the original appearance of the object has been subject to varying interpretations. It has been read as a type of censorship, a way of diluting the obscenity of the splayed vagina, of resisting and reversing what is inappropriate in a Christian context. Alternatively, it has been suggested that the bits of extracted stone could have been used in magical potions.[55]

How exactly the gaping vaginal holes of the sheela-na-gigs are to be interpreted depends at least in part on the viewer. Is it an unveiling of that which usually remains hidden, for reasons perhaps warningly apotropaic? A passive invitation to penetration? A voracious hell-mouth entrance hungry to consume?[56] A benign or even magical reproductive exit? The ultimate display of girl power? From the distaste of the antiquarians to the embrace of some feminists, without a clear understanding of the way the sheela-na-gigs functioned in their original context, we are forced at least partially to construct the context ourselves, and in doing so, perhaps we reveal more about ourselves and our own predilections than we do about the subjects of our study.[57] These open questions about the original contexts and functions of the sheela-na-gigs work against the prevailing scholarly view that historical context plays a primary role in understanding the significance of a work of art. The triangulation model allows for a more nuanced understanding of objects such as sheela-na-gigs by allowing the past and the present, underpinned by theory, to press the understanding of the object in new directions.

In medieval religious art, there are sometimes images that are powerfully explicit, and for this reason seem to be often overlooked in contemporary scholarship. Somewhat paradoxically, secular images, especially those associated with courtly love, illustrate direct physical erotic experience but often do so in metaphorical terms; in reading these images in conjunction with medieval literature such as romances, pastourelles, and fabliaux, in which sexual encounters (usually seduction/rapes described from the male point of view) are bawdily if euphemistically recounted, it becomes clear that the chaplets, roses, falcons, squirrels, rabbits, swords, chess games, and castle-stormings are thinly-veiled sexual puns. In part due to the amount of surviving material, but probably also based on the seeming appropriateness, secular objects, particularly those with sexualized themes, are also seldom the subjects of scholarly study.[58]

Fig. 17. Mirror case, made in Paris, ca. 1320. Paris, Musée du Louvre.

The luxury trade in ivory mirrorbacks, combs, and caskets in the fourteenth century produced large numbers of objects with images of heterosexual couples. A mirror, rare in that both front and back survive intact, shows eight scenes of couples, visualizing the various possibilities and positions of courtship (Fig. 17).[59] One of the most prominent objects exhibited on the mirror is the chaplet, the round object held in each case by the woman. Sometimes she hides it behind her back, sometimes she dangles it tantalizingly out of reach, ultimately she “crowns” her successful suitor with her favor. The chaplet, in its circular construction, becomes a vaginal metaphor for the consummation of the courtship dance. Similarly, a comb seems to present a progression of courtship: on the left, the man holds a falcon and the woman some kind of small animal, perhaps a dog (Fig. 18).[60] The falcon is a literary motif mentioned by Capellanus and other authors as a symbol for the sport of flirtation and the conquest of love;[61] the dog as a figure of fidelity, but also of male and female sexuality. In the middle, the lover is crowned; on the right, the woman chucks the man under the chin while he encircles her waist with one hand and caresses her crotch with the other. In another mirror case, a couple sets off on horseback with displaced symbols of their genitalia, the man with a sword handle or pommel erect at his crotch, while a rabbit, (‘con’ in Old French), mounted by a dog in the lower quadrant of the mirror, provides a visual and linguistic pun for the female genitalia (Fig. 19).[62]

Fig. 18. Comb, made in Paris, ca. 1320-30. London, Victoria and Albert Museum.

Fig. 19. Mirror case, made in Paris, ca. 1320. London, Victoria and Albert Museum.

Fig. 20. Mirror case, made in Paris, ca. 1320- 40. Baltimore, Walters Art Museum (71.169).

A particularly popular theme in the iconography of courtly love is the storming of the Castle of Love (Fig. 20).[63] Knights fully equipped with armor, swords and horses attack a castle populated solely by women, who tepidly defend themselves and perhaps welcome their attackers by throwing roses, flowers with vaginal connotations.[64] The castle itself becomes a metaphor for the female body, the castle gates an orifice waiting to be penetrated.[65] The climactic scene in the Roman de la Rose, the most popular work of literature in the fourteenth century, where the protagonist Amant finally seduces/rapes the Rose, the object of his desire and pursuit, the text describes the ultimate scene of seduction as an attack and forced entrance upon a barricaded structure, with the body of the Rose described as an “ivory tower” and her legs as “fair pillars.”[66] Amant further uses his “staff” to break down the obstructed “little opening.” Some illustrations in Roman de la Rose manuscripts show Amant thrusting his sword into a window-like opening in the Rose, whose lower body appears as an architectural form.[67] In spite of the similarities between the iconography of the castle of love, which can be found in manuscripts as well as ivories, and the scene of sexual consummation between Amant and the Rose, the connection between these two sources has never really been made;[68] despite some attempts at more nuanced interpretation, much of the scholarship on medieval ivories tends toward the narrowly iconographic and curatorial, generally overlooking issues of gender and sexuality.

Purportedly women owned most of the ivory mirror cases, combs, caskets and other items that are decorated with courtly love themes. Although it is unclear whether women procured these items themselves, or if they were gifts from men, there has been little consideration of how these female owners might have responded to the iconography of courtly love.[69] Even in more recent explorations of sexualities in medieval culture and art, the possibility of pleasure in the gaze, and specifically female pleasure, has been rarely mentioned. Much of the feminist scholarship on medieval art, following Mulvey, examines the misogynist male gaze on the female body, or the way women, socialized in patriarchal culture, must co-opt the male gaze to glean hetero-normative and socially sanctioned visual meaning. This overlooks the visual pleasures possible for a woman viewing a scene ripe with sexual metaphor and thwarts the possibilities of the pleasurable female gaze on the female body as well as the appreciative female gaze on the male body. It has been argued that women might have taken an interest in the depictions of female martyrs because of their understanding that with their suffering came power, but could more erotic responses have been possible as well? And why is it that the naked men depicted in medieval art, or in any art for that matter, are typically described as homoerotic? Images of Saint Sebastian are routinely characterized in this way, and he has in fact become a kind of gay icon.[70] Thus the male gaze on the male body is taken into account in a way that the female gaze on the male body, or the female gaze on the female body, is not.[71]

Fig. 21. The Torture of St. Agatha, Picture Book of Madame Marie, northern France, late 13th century, Pairs, Bibliothèque National de France, n.a. fr. 16251, fol. 97v.

The mostly nude, eroticized Sebastian, shot through with arrows, stands in contrast to most late medieval depictions of male saints, who are usually clothed. The thirteenth-century Picture Book of Madame Marie appears to reverse the more typical convention of clothed male martyrs and unclothed female martyrs; the only female martyr depicted in any degree of undress is Agatha (Fig. 21), and even she is almost entirely covered, except for the exposed bits of flesh necessary to show the gruesome method of her torture.[72] This depiction stands apart: not only do most images of Agatha’s torture depict her naked from the waist up, but nearly all also show Agatha’s unblemished, perfect breasts. In Madame Marie’s book, the nipples are in the process of being cut off, with blood freely flowing as torturers enthusiastically wield their giant pincers. Alison Stones has suggested that the particularities of this manuscript underscore its connection to a female owner: Stones sees the mastectomy of Agatha as reminiscent of a mother’s experience of teething babies biting while they nurse. In the particularly horrific disembowelment of Vincent, Stones recognizes allusions to Caesarian births.[73] Taking this gender association one step further, I would posit that the lack of female nudity, particularly with saints such as Barbara, Catherine, Lucy, and other martyrs who are often represented in erotically charged ways in other medieval images, as well as the contrasting presence of male nudity, suggests that Madame Marie was thus facilitated in her heterosexual responses, devotional and otherwise.

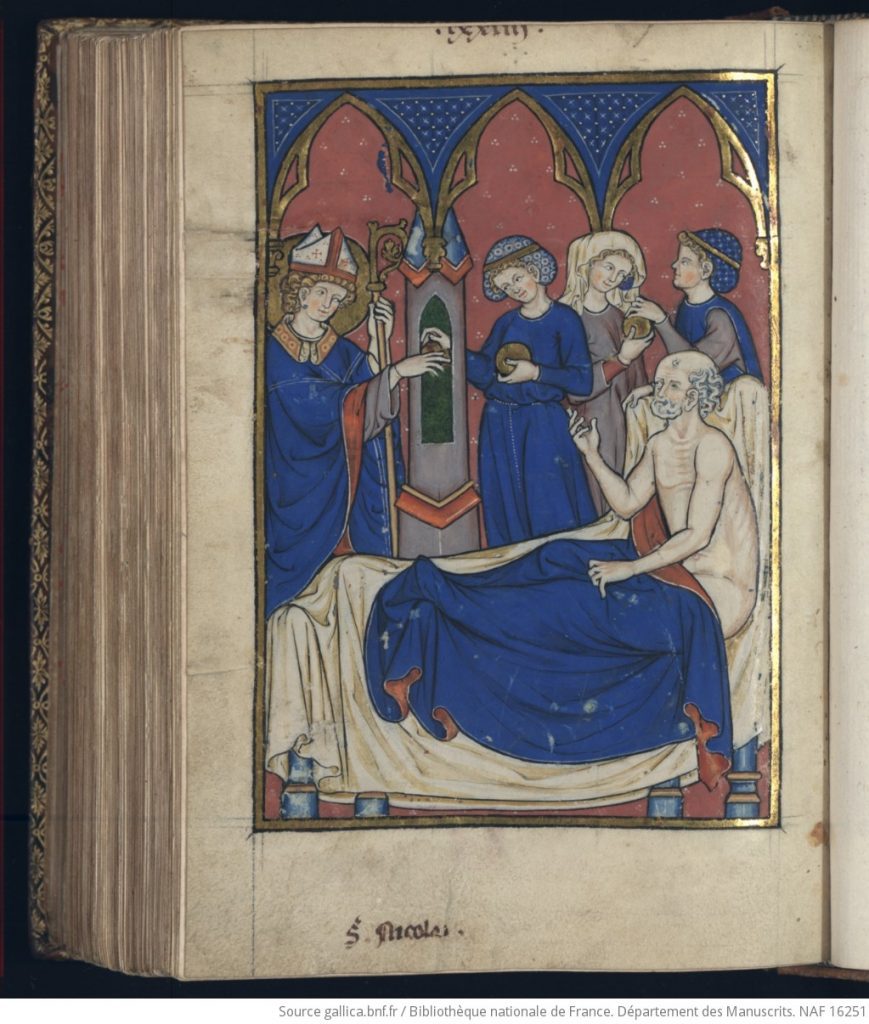

Fig. 22. St. Nicholas, Picture Book of Madame Marie, northern France, late 13th century, Pairs, Bibliothèque National de France, n.a. fr. 16251, fol. 90v.

A particularly evocative image is that of the charity of Saint Nicholas (Fig. 22), who hands gold coins through a window to help three daughters of a sick and infirm man avoid turning to prostitution. The daughters are fully clothed with modest hairstyles and coverings; the sick father sits up in bed with his blankets slipping away, his virile nudity belying his supposed illness. Other visual cues, particularly the combination of the phallic tower and the dark vaginal space of the window through which Saint Nicholas reaches, suggest further interpretations and responses beyond the initial devotional reading.

Fig. 23. Couple in bed, Aldobrandino of Siena’s Le Régime de Corps, Lille, ca. 1285. London, British Library, MS Sloane 2435, fol. 9v.

We need to think further about how women might have responded to the visual images that they saw on a daily basis, not only in their devotional manuals, but also depicted in the secular objects, such as ivories, that surrounded at least some women in their daily lives. Why is it that the imagery in the iconography of courtly love is so much less explicit, and rather more suggestively nuanced? This seems to be a case in which visual puns, derived from medieval literature, have less impact in image than text. Like the metaphorical substitutes of chaplet-crownings and castle-stormings for sexual activity, even when couples are represented in bed in secular manuscripts such as romances or even medieval sex manuals, they are somewhat modestly/discretely portrayed in that their bodies are concealed with bedclothes (Fig. 23),[74] with phallic candles and labial curtains standing in for the depiction of actual genitals,[75] although there are occasions when sexual activity seems to be more explicitly indicated (Fig. 24).[76]

Fig. 24. Couple in bed, Roman de la Rose, France, ca. 1380. London, British Library, MS Egerton 881, fol. 126r.

Yet even these more decorous images of couples in bed can occasion the dismay of later viewers and perhaps give an insight to the resistance of scholars of medieval art to engage with these images; Camille has discussed not only the various contexts within which these couples appear, particularly in Latin and vernacular medical treatises and romances dating from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, but also their later censorship effected by scraping or rubbing away the offending images.[77] He suggests these erasures began to appear in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, at a time when the idea of privacy and the increasing social control over the body and sexuality changed the perception of such images. To provide further context for such images we turn to Jeremy Goldberg’s analysis of disputes over the validity of marriages recorded in the York cause papers, or records of church courts.[78] To prove consummation as evidence of part of the contract between the parties, particularly when either one denied that sex had taken place, there had to be evidence that the couple had been seen naked together in bed; Goldberg points out that it might be surprising for us to learn how frequently such behavior was in fact witnessed, but he also points out that such observations seem to decline by the fifteenth century. The increasing proliferation of bed hangings, separate chambers for sleeping, and attitudes about privacy, and the resultant effects on the activities of bathing, dressing, and lovemaking, meant that what was once out in the open became increasingly hidden. What is hidden then becomes desirable; stolen glances at the private become voyeuristic, and the mundane becomes erotic. Paul Saenger has suggested that the advent of silent reading had a profound effect on medieval culture; a silent reader could read whatever he wanted, wherever and whenever he wanted. Saenger suggests that the change from oral to silent reading, from public to private consumption of text and image, led to an increasing interest in erotic writings and art.[79] On the other hand, the fifteenth century was also the time that the isolated wounds of Christ mentioned earlier become reoriented from a vertical to a horizontal position, and become almost schematized in their appearance, as if the more prurient aspects of the vertical orientation now recognized become problematic.[80]

The increasing regulation of both social behavior and artistic production seems to have carried over into traditional modern scholarship on medieval art, privileging religious readings over secular or sexual ones, creating a reluctance to engage with sexuality, and especially with sexual imagery. It seems that most of the scholars discussing sex and eroticism in the Middle Ages focus on texts, such as mystical writings, medieval literature, or canon law. But visual images, perhaps even more than written words, can have a multiplicity of meanings, even for the same person. Yet the definition of the terms ‘erotic,’ ‘pornographic,’ ‘obscene,’ is as elusive as ever in our own modern culture, and censorship still a minefield of politics, religion, and ideology. Thus some feminists find themselves strange bedfellows with those who align themselves with the religious right in their attitudes toward pornography, while at the same time some young women on college campuses edit, write for, and pose in erotic campus publications, thus reclaiming the display of their own sexuality.[81] This latter phenomenon may point to the new directions emerging in the study of medieval visual culture; in a sex-positive culture, at least in certain circles, and with the increasingly mainstream disciplines of feminism, queer theory, and other methodologies that help to rethink traditional art historical approaches and draw attention to areas previously overlooked, it may be that increasingly scholars work, even unconsciously, from a particular position, select what engages them on a personal level, and therefore look for the sexual instead of the religious. And thus the modern conception of what constitutes “medieval art” is subject yet again to how we look and what we think.

Martha Easton teaches at Bryn Mawr in the Department of the History of Art. Her research and teaching interests include medieval illuminated manuscripts, gender and hagiography, the history of collecting medieval art, and feminist theory. Her current project focuses on representations of the tortures of male and female martyrs, and their complicated meanings for medieval viewers. She is the author of numerous publications on issues of gender, eroticism and sanctity in medieval visual culture.

References

| ↑1 | For more on mysticism, see Sarah Salih, “When is a Bosom Not a Bosom? Problems with ‘Erotic Mysticism’,” in Medieval Virginities, ed. Anke Bernau, Ruth Evans, and Sarah Salih (Toronto and Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 2003), 14-32; Nancy F. Partner, “Did Mystics Have Sex?” in Desire and Discipline: Sex and Sexuality in the Premodern West, ed. Jacqueline Murray and Konrad Eisenbichler (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1996), 296-31. https://doi.org/10.3138/9781442673854-017; Julie B. Miller, “Eroticized Violence in Medieval Women’s Mystical Literature: A Call for a Feminist Critique,” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 15 (1999): 25-49. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Leo Steinberg, The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion (New York: Pantheon Books, 1983); Caroline Walker Bynum, “The Body of Christ in the Later Middle Ages: A Reply to Leo Steinberg,” Renaissance Quarterly 39 (1986): 399-439, rpt. in Bynum, Fragmentation and Redemption: Essays on Gender and the Human Body in Medieval Religion (New York: Zone Books, 1992), 79-117; Leo Steinberg, The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion, 2nd ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996); see in particular the added section “Ad Bynum.” Among the several discussions of the debate, see Martha Easton, “Saint Agatha and the Sanctification of Sexual Violence,” Studies in Iconography (1994): 84-5; and Robert Mills, “Ecce Homo,” in Gender and Holiness: Men, Women and Saints in Late Medieval Europe, eds. Samantha J.E. Riches and Sarah Salih (London and New York: Routledge, 2002), 154-8. |

| ↑3 | Karma Lochrie, “Mystical Acts, Queer Tendencies,” in Constructing Medieval Sexuality, eds. Karma Lochrie, Peggy McCracken, and James Schultz (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997), 180-200; Mills, “Ecce Homo,” 15273; Richard Trexler, “Gendering Christ Crucified,” in Iconography at the Crossroads, ed. Brendan Cassidy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993), 107-19. |

| ↑4 | Some cautions about Lochrie’s approach are offered in Martha Easton, “The Wound of Christ, the Mouth of Hell: Appropriations and Inversions of Female Anatomy in the Later Middle Ages,” in Tributes to Jonathan J.G. Alexander: The Making and Meaning of Illuminated Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts, Art and Architecture, eds. Susan L’Engle and Gerald B. Guest, (London/Turnhout: Harvey Miller Publishers, 2006), 397. |

| ↑5 | See for example the image in the Passionale of Abbess Cunegonde (Prague, The National Library of the Czech Republic, MS xiv a 17, fol. 16v); for an illustration see Michael Camille, The Medieval Art of Love: Objects and Subjects of Desire (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1998), 134, fig. 121. |

| ↑6 | For more discussion of the iconography of the Sponsa/Sponsus, see Sarit Shalev-Eyni, “Iconography of Love:Illustrations of Bride and Bridegroom in Ashkenazi Prayerbooks of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Century,” Studies in Iconography 26 (2005): 27-57; Michael Camille, “Gothic Signs and the Surplus: The Kiss on the Cathedral,” Yale French Studies, spec. ed., Contexts: Style and Values in Medieval Art and Literature, eds. Daniel Poirion and Nancy Freeman Regalado (1991): 151-70; Jeffrey F. Hamburger, The Rothschild Canticles: Art and Mysticism in Flanders and the Rhineland circa 1300 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990); and Sarah Bromberg, “Gendered and Ungendered Readings of the Rothschild Canticles,” in this volume. |

| ↑7 | For discussion and images, see Easton, “The Wound of Christ.” |

| ↑8 | For more on medieval medical beliefs about blood and milk, see Marie-Christine Pouchelle, The Body and Surgery in the Middle Ages, trans. Rosemary Morris (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1990), 156. See also the bibliography in Easton, “The Wound of Christ, the Mouth of Hell,” 399 n. 29. |

| ↑9 | I explore these inversions further in “The Wound of Christ, the Mouth of Hell,” 395-414. |

| ↑10 | Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Douce 6, fol. 160v. For an illustration and discussion, see Camille, Image on the Edge, 122-3 (figs. 64-65); 141. |

| ↑11 | Tertullian, De cultu feminarum: “You are the gateway of the devil.” Reproduced in Women Defamed and Woman Defended: An Anthology of Medieval Texts, ed. Alcuin Blamires (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), 51; Third Day, Tenth Story. Giovanni Boccaccio, The Decameron (New York: Penguin, 1982), 235-39. |

| ↑12 | For more on the correlations between nudity and innocence, see Wayne A. Meeks, “The Image of the Androgyne: Some Uses of a Symbol in Earliest Christianity,” History of Religions 3 (1974), 165-208 and Linda Seidel, “Adam and Eve: Shameless First Couple of the Ghent Altarpiece” in this volume. https://doi.org/10.1086/462701 |

| ↑13 | For the manuscript see Millard Meiss, The Belles Heures of Jean, Duke of Berry (New York: Braziller, 1974); and Jean Porcher, ed., Les Belles Heures de Jean de France, Duc de Berry (Paris: Bibliothèque nationale, 1953.) For an image, see Porcher, fig. CXVIII. |

| ↑14 | Margaret R. Miles, Carnal Knowing: Female Nakedness and Religious Meaning in the Christian West (Boston: Beacon Press, 1989), 156; Madeline H. Caviness, Visualizing Women in the Middle Ages: Sight, Spectacle, and Scopic Economy (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2001); see especially chapter 2, “Sado-Erotic Spectacles, Breast Envy, and the Bodies of Martyrs,” 83-124. |

| ↑15 | Jacobus de Voragine, The Golden Legend: Readings on the Saints, trans. William Granger Ryan, Vol. 1 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993), 155; see the discussion in Easton, “Saint Agatha,” 93-98. |

| ↑16 | For more on scopophilia, see Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” Screen 16 (1975): 6-18; rpt. in her Visual and Other Pleasures (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989). https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/16.3.6 |

| ↑17 | Andreas Capellanus, The Art of Courtly Love, trans. John Jay Parry (1941; rpt. New York: Columbia University Press, 1990), 28. |

| ↑18 | For further discussion of David and Bathsheba, see Michael Camille, The Gothic Idol: Ideology and Image-making in Medieval Art (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 302-3; and Thomas Kren, “Looking at Louis XII’s Bathsheba,” in A Masterpiece Reconstructed: The Hours of Louis XII, ed. Thomas Kren (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2005), 42-61. |

| ↑19 | Chantilly, Musée Condé, MS 16, Très Riches Heures of Jean, Duke of Berry, fol. 25v. See Jean Longon, Raymond Cazelles, Millard Meiss, The Très Riches Heures of Jean, Duke of Berry. Musée Condé, Chantilly (New York: George Braziller, 1969). For an image, see Longon et al., no. 20. |

| ↑20 | For more information about the development of this motif, see Nona C. Flores, “Effigies amicitiae…veritas inimicitiae”: Antifeminism in the Iconography of the Woman-Headed Serpent in Medieval and Renaissance Art and Literature,” in Animals in the Middle Ages, ed. Nona C. Flores (New York: Routledge, 2000), 167-96. |

| ↑21 | For discussion of an alternate view of the possible sexuality and gendered viewing of Jean de Berry, see Michael Camille, “For Our Devotion and Pleasure: The Sexual Objects of Jean, Duc de Berry,” Art History 24, 2 (April 2001): 169-94. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8365.00259 |

| ↑22 | For more on depictions of class in the manuscript, see Jonathan J.G. Alexander, “’Labeur and Paresse: Ideological Representations of Medieval Peasant Labor,” Art Bulletin 72 (1990): 436-52. https://doi.org/10.2307/3045750 |

| ↑23 | For an image, see Longon et al., Très Riches Heures, no. 3. |

| ↑24 | For an image, see Longon et al., Très Riches Heures, no. 9. |

| ↑25 | Madeline Caviness has discussed the ‘labial’ drapery folds and their potential meaning, in both secular and religious contexts. See Madeline H. Caviness, “Obscenity and Alterity: Images that Shock and Offend Us/Them, Now/Then?” in Obscenity: Social Control and Artistic Creation in the European Middle Ages, ed. Jan M. Ziolkowski (Leiden: Brill,1998), 165; Madeline H. Caviness, “Patron or Matron? A Capetian Bride and a Vade Mecum for Her Marriage Bed,” in Studying Medieval Women: Sex, Gender, Feminism, ed. Nancy F. Partner (Cambridge: The Medieval Academy of America, 1993), 40. |

| ↑26 | For an image, see James J. Rorimer, The Belles Heures of Jean, Duke of Berry Prince of France (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1958), no. 12. |

| ↑27 | Jacobus de Voragine, The Golden Legend, Vol. 2, 334-41. |

| ↑28 | For further discussion of this point, see Easton, “Saint Agatha,” 97; and Martha Easton, “Pain, torture and death in the Huntington Library Legenda aurea,” in Gender and Holiness, 57-61. |

| ↑29 | For an image, see Porcher, Les Belles Heures, fig. CXXXIV. |

| ↑30 | For more on these saints and the connections between them, see Ruth Mazo Karras, “Holy Harlots: Prostitute Saints in Medieval Legend,” Journal of the History of Sexuality 1, 1 (July 1990): 3-32. |

| ↑31 | For more on the wild man, see Lorraine Kochanske Stock, The Medieval Wild Man (New York: Palgrave, 2005); Timothy Husband, with the assistance of Gloria Gilmore-House, The Wild Man: Medieval Myth and Symbolism (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1980). For a comparable illustration see the image of the wild man and woman in Les Quatre États de la société, Paris, École des beaux-arts, M. 90-93, reproduced in François Avril and Nicole Reynaud, Les manuscripts à pentures en France 1440-1520 (Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France, 1993), 302. |

| ↑32 | Bynum, “The Body of Christ,” Fragmentation and Redemption, 86; Beth Williamson, “The Virgin ‘Lactans’ as Second Eve: Image of the ‘Salvatrix,’” Studies in Iconography 19 (1998): 105-138; Beth Williamson, “Liturgical Image or Devotional Image? The London ‘Madonna of the Firescreen’ in Objects, Images, and the Word: Art in the Service of the Liturgy, ed. Colum Hourihane (Princeton: Index of Christian Art, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University in association with Princeton University Press, 2003), 298-318. |

| ↑33 | Margaret R. Miles, “The Virgin’s One Bare Breast: Female Nudity and Religious Meaning in Tuscan Early RenaissanceCulture,” in The Female Body in Western Culture, ed. Susan Rubin Suleiman (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1986), 193-208. |

| ↑34 | See François Avril, Jean Fouquet: Peintre et enlumineur du XVe siècle (Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France, 2003), 25-30, with accompanying illustrations. For more discussion of the image, see Kren, 53. |

| ↑35 | See Sensation: Young British artists from the Saatchi Collection (London: Thames and Hudson in association with the Royal Academy of Arts; New York: Thames and Hudson), 1998, 133. |

| ↑36 | For more on Ofili, see Chris Ofili: Afromuses 1995-2005, ed. Ali Evans (New York: The Studio Museum in Harlem, 2005). |

| ↑37 | Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, cod. 2554 (Bible moralisée), fol. 2. See discussion, as well as an image, in Camille, The Medieval Art of Love, 138-39; and Camille, The Gothic Idol, 90-92. This image was also discussed by Robert Mills, “French Kisses: Sodomy and Sin in the Bible moralisée Tradition,” paper delivered at the 2005 International Congress on Medieval Studies, Kalamazoo, Michigan for the session, “The Queer Kiss,” sponsored by the Centre for Late Antique and Medieval Studies, King’s College London. For more on the manuscript itself, see Gerald B. Guest, Bible Moralisée (Codex Vindobonensis 2554, Vienna, Osterreischische Nationalbibliothek) (London: Harvey Miller Publishers, 1995). |

| ↑38 | See Anthony Weir and James Jerman, Images of Lust: Sexual Carvings on Medieval Churches (London: B.T. Batsford, 1986). |

| ↑39 | For more on misericords, see Christa Grössinger, The World Upside-Down: English Misericords (London: Harvey Miller, 1997). |

| ↑40 | See especially Michael Camille, “Dr Witkowski’s Anus: French Doctors, German Homosexuals and the Obscene in Medieval Church Art” in Medieval Obscenities, ed. Nicola McDonald (York: York Medieval Press, 2006), 17-38. |

| ↑41 | Michael Camille, Image on the Edge: The Margins of Medieval Art (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992). |

| ↑42 | The classic study of the carnivalesque is Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, trans. Hélène Iswolsky (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984). |

| ↑43 | For more on these badges, see Nicola McDonald, “Introduction,” in Medieval Obscenities, especially 2-11; Jos Koldeweij, “Shameless and Naked Images: Obscene Badges as Parodies of Popular Devotion,” in Art and Architecture of Late Medieval Pilgrimage in Northern Europe and the British Isles, eds. Sarah Blick and Rita Tekippe (Leiden: Brill, 2005), 493-510; A.M. Koldeweij, “A Barefaced ‘Roman de la Rose’ (Paris, B.N., ms. fr. 25526) and Some Late Medieval Mass-Produced Badges of a Sexual Nature, in Flanders in a European Perspective: Manuscript Illumination around 1400 in Flanders and Abroad. Proceedings of the International Colloquium Leuven, 7-10 September 1993. Corpus of Illuminated Manuscripts, 8 (Low Countries Series 5), eds. Maurits Smeyers and Bert Cardon (Leuven, Uitgeverij Peeters, 1995), 499-516; Malcolm Jones. “Secular Badges,” in Rotterfam Papers VIII: Heilig en Profaan. 1000 laatniddeleeuwse Insignes uit de collecctie H.J.E. van Beuningen (Cothen, 1993), 99-108; Jan Baptist Bedeaux, “Laatmiddeleeuwse sexuele amuletten,” in Annus Quadrigia Mundi: Opstellen over Middeleeuwse Kunst (Trecht: De Walburg, 1989). |

| ↑44 | Paula Gerson, “Margins for Eros,” Romance Languages Annual 5 (1993): 47- 53; Camille, Image on the Edge, 53-54; for an illustration, 49 fig. 24. |

| ↑45 | The idea of the aggressive image assaulting the viewer is discussed in Easton, “Saint Agatha,” 101. For more on the gaze, see also Caviness, Visualizing Women, 17-44. |

| ↑46 | See the useful summary of earlier scholarship in Barbara Freitag, Sheela-na-Gigs: Unravelling an Enigma (London and New York: Routledge, 2004).16-51. |

| ↑47 | Jørgen Anderson, The Witch on the Wall: Medieval Erotic Sculpture in the British Isles (London: Allen and Unwin), 1977. |

| ↑48 | Eamonn Kelly, “Irish Sheela-na-gigs and Related Figures with Reference to the Collections of the National Museum ofIreland,” in Medieval Obscenities,124-37; Patrick K. Ford, “The Which on the Wall: Obscenity Exposed in Early Ireland,” in Obscenity: Social Control, 76-90. |

| ↑49 | Ford, 176. |

| ↑50 | For more information on the image, see Josephine Withers, “Nancy Spero’s American-born Sheela-na-gig,” Feminist Studies 17 (1991): 51-56. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178169 |

| ↑51 | See Marian Bleeke, “Sheelas, Sex, and Significance in Romanesque Sculpture: The Kilpeck Corbel Series,” Studies in Iconography 26 (2005); 1-26, with accompanying illustrations. |

| ↑52 | Freitag, Sheela-na-Gigs. |

| ↑53 | Catherine E. Karkov, “Sheela-na-gigs and Other Unruly Women: Images of Land and Gender in Medieval Ireland; inFrom Ireland Coming: Irish Art from the Early Christian to the Late Gothic Period and Its European Context, ed. Colum Hourihane (Princeton, Index of Christian Art, Dept. of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University in association with Princeton University Press, 2001), 313-331. |

| ↑54 | Lisa M. Bitel, Land of Women: Tales of Sex and Gender from Early Ireland (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1996). |

| ↑55 | Caviness, “Obscenity and Alterity, 166. |

| ↑56 | For connections between the vagina, mouth, and hell mouth, see Easton, “The Wound of Christ,” 402-04. |

| ↑57 | For more on the changing significance and interpretation of vaginal iconography in general see Madeline H. Caviness,“Revisiting Vaginal Iconography,” Quintana 6 (2007): 13-37. |

| ↑58 | There are very few publications on this material that attempt to examine it using more theoretical methodologies. Exceptions include Susan L. Smith, “The Gothic Mirror and the Female Gaze,” in Saints, Sinners, and Sisters: Gender and Northern Art in Medieval and Early Modern Europe, ed. Jane L. Carroll and Alison G. Stewart (London: Ashgate, 2003), 73-93; Camille, The Medieval Art of Love; and C. Jean Campbell, “Courting, Harlotry and the Art of Gothic Ivory Carving,” Gesta 34 (1995): 11-20. https://doi.org/10.2307/767120 |

| ↑59 | For an illustration, see Camille, The Medieval Art of Love, 54 fig. 39. |

| ↑60 | For an illustration, see Camille, The Medieval Art of Love, 56, figs. 41 and 42. |

| ↑61 | For more information on the symbolic significance of the hunt, see Mira Friedman, “The Falcon and the Hunt: Symbolic Love Imagery in Medieval and Renaissance Art,” in Poetics of Love in the Middle Ages: Texts and Contexts (Fairfax, VA: George Mason University, 1989); Marcelle Thiébaux, The Stag of Love: the Chase in Medieval Literature (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1974). |

| ↑62 | For animals as erotic metaphors, see Lucy Freeman Sandler, “A Bawdy Bethrothal in the Ormesby Psalter,” in A Tribute to Lotte Brand Philip: Art Historian and Detective, ed. William Clark et al. (New York: Abaris Books,1985), 15459; Malcolm Jones, “Folklore Motifs in Late Medieval Art iii: Erotic Animal Imagery,” Folklore, 102 (1991): 192-219. For an illustration, see Camille, The Medieval Art of Love, 101 fig. 86. https://doi.org/10.1080/0015587X.1991.9715820 |

| ↑63 | For an illustration, see Peter Barnett, Images in Ivory: Precious Objects of the Gothic Age (Detroit: Detroit Institute of Arts, 1997), 230. |

| ↑64 | See, for example, the discussion in Helen Solterer, “At the Bottom of Mirage, a Woman’s Body: Le Roman de la rose of Jean Renart,” in Feminist Approaches to the Body in Medieval Literature, New Cultural Studies, ed. Linda Lomperis and Sarah Stanbury (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press,1993), 213-33. |

| ↑65 | Suzanne Lewis, “Images of Opening, Penetration and Closure and the Roman de la Rose,” Word and Image 8 (1992): 215-42. https://doi.org/10.1080/02666286.1992.10435839 |

| ↑66 | For the text see E. Langlois, ed., Roman de la Rose, 5 vols. (Paris, 1914); and Charles Dahlberg, trans., Romance of the Rose (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1971). See also Kevin Brownlee and Sylvia Huot, eds., Rethinking the Romance of the Rose: Text, Image, Reception, Middle Ages Series (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992). |

| ↑67 | Valencia, Valencia University Library, MS 387, fol. 146v. For an illustration, see Camille, Medieval Art of Love, 152, fig. 140. |

| ↑68 | The connection has even been explicitly rejected, but for reasons that seem ambiguous at best. See Clifton C. Olds, Ralph G. Williams, and William R. Levin, Images of Love and Death in Late Medieval and Renaissance Art (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Museum of Art, 1976), 106-08, which also lists two other sources rejecting the connection: Raymond Koechlin, Les Ivoires Gothiques Français (Paris: A. Picard, 1924, reprinted 1968); and David J.A. Ross, “Allegory and Romance on a Medieval French Marriage Casket,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, XI (1948): 112-142. |

| ↑69 | For a discussion of the way a female owner might have responded to sexual imagery on a Greek mirror, see Andrew Stewart, “Reflections,” Sexuality in Ancient Art, ed. Natalie Boymel Kampen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 136-54. https://doi.org/10.2307/750464 |

| ↑70 | Richard A. Kaye, “Losing His Religion: Saint Sebastian as Contemporary Gay Martyr,” in Outlooks: Lesbian and Gay Sexualities and Visual Cultures, ed. Peter Horne and Reina Lewis (New York: Routledge, 1986), 205-12. |

| ↑71 | See, however, Sarah Kent, “The Erotic Male Nude,” in Women’s Images of Men, ed. Sarah Kent and Jacqueline Morreau (London: Writers and Reader Publishing, 1985), 75-105. |

| ↑72 | Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS n.a. fr. 16251. For the manuscript and reproductions in color of the illuminations, see Alison Stones, Le Livre d’images de Madame Marie: Reproduction intégrale du manuscript Nouvelles acquisitions françaises 16251 de la Bibliothèque Nationale de France (Paris: Les editions du Cerf – Bibliothèque nationale de France, 1997). For a discussion of nudity and martyrdom, see Easton, “Pain, torture and death,” 57-61. |

| ↑73 | Alison Stones, “Nipples, Entrails, Severed Heads, and Skin: Devotional Images for Madame Marie,” in Image and Belief: Studies in Celebration of the Eightieth Anniversary of the Index of Christian Art, ed. Colum Hourihane (Princeton: Index of Christian Art, 1999), 48-70. |

| ↑74 | For discussion and an illustration, see Camille, The Medieval Art of Love, 142-44, fig. 130. |

| ↑75 | Michael Camille, “Manuscript Illumination and the Art of Copulation,” in Constructing Medieval Sexuality, 62. |

| ↑76 | Couple in bed, Roman de la Rose, France, c. 1380 (London, British Library, MS Egerton 881, fol. 126r). For discussion and an illustration see Camille, The Medieval Art of Love, 147-8, fig. 134. |

| ↑77 | Michael Camille, “Obscenity Under Erasure: Censorship in Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts,” in Obscenity: Social Control, 139-154. |

| ↑78 | Jeremy Goldberg, “John Skathelok’s Dick: Voyeruism and ‘Pornography’ in Late Medieval England,” in Medieval Obscenities, 105-123. |

| ↑79 | Paul Saenger, “Silent Reading: Its Impact on Late Medieval Script and Society,” Viator 13 (1982): 412-13. https://doi.org/10.1484/J.VIATOR.2.301476 |

| ↑80 | Easton, “The Wound of Christ,” 408. |

| ↑81 | See Jodi Rudoren, “The Student Body,” Education Life, The New York Times, Sunday April 23, 2006. |