Dana Oswald • University of Wisconsin, Parkside

Recommended citation: Dana Oswald, “Unnatural Women, Invisible Mothers: Monstrous Female Bodies in the Wonders of the East,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 2 (2010). https://doi.org/10.61302/BVFS9924.

For all of the people who clearly must have been born in Anglo-Saxon England, there are very few mothers present to give birth to them in Old English literature. Anglo-Saxon mothers seem to occupy a position of social discomfort. Not only are they at the troubling center of the cultural dilemma of peace-weaving, but they possess bodies that exceed the understanding of literate monks and noblemen. The maternal body seems to be an object of shameful excess, and therefore is the body least likely to be witnessed in Anglo-Saxon art and literature—that is, unless it is the virgin body of Mary, appropriately sealed up and removed from circulation. The non-virginal maternal body, then, presents an intriguing dichotomy; it is at once necessary for the continuation of patriarchal lineage, and disruptive to that lineage. In the language of feminist psychoanalysis, the Anglo-Saxon mother is an archaic mother—one defined by her generative power, but necessary thereby to abject from the record. However, she circulates just below the surface of Anglo-Saxon texts, interrupting the master narrative each time a child is born. She remains nameless, but her presence in literary and artistic culture cannot be excluded entirely because of her generative potential. This is particularly so in the Anglo-Saxon Wonders of the East, a text populated by monsters born to mothers who remain largely invisible in both word and image. In addition, the only monstrous women featured in Wonders are gender hybrids, creatures that challenge the integrity of the sexed and gendered body and also reconfigure the very nature of reproduction and maternity.

In Anglo-Saxon lineages, fathers’ names are prominent, while mothers’ names appear rarely, if at all. As Mary Dockray-Miller states, “In Anglo-Saxon culture at large, both during and after Bede, patrilineage was the focus of most extant genealogy; such a patrilineal focus was also coupled with a usual exclusion of women’s roles and names at all, erasing and eliding the biologically crucial maternal body from both the family tree and the historical focus.”[1] Thus, mothers are written out of questions of lineage and out of the literature that perpetuates and reflects this patriarchal culture. This element of removal, however, highlights the power of these women’s bodies: their ability to reproduce makes the family tree possible. As Julia Kristeva argues, “Fear of the archaic mother turns out to be essentially fear of her generative power. It is this power, a dreaded one, that patrilineal filiation has the burden of subduing.”[2] In order to subdue the archaic mother, Kristeva suggests that this patrilineal filiation constructs the maternal body as abject—that which has been defiled and must be extruded. The authors of Anglo-Saxon literature seem to perform this abjection not only by writing mothers out of lineages but also by excluding them almost entirely from the literary record.

Named mothers present in Old English literature can be counted on two hands, the most familiar of whom are the eponymous Elene and the five mothers in Beowulf: Wealhpeow, Hildeburgh, Hygd, Modpryd, and, of course, Grendel’s mother. Indeed, the scholarship on Anglo-Saxon mothers is limited to a single book-length study, Mary Dockray-Miller’s Motherhood and Mothering in Anglo- Saxon England. Shorter studies on mothering during this period are also comparably rare, and mostly focused on one of three topics:[3] (1) religious women who, in their positions of authority as abbesses, take on maternal roles (e.g., Hild of Whitby);[4] (2) queens who act as mothers, metaphorically, to their nations (e.g., Ædelflæd, Lady of the Mercians)[5]or literally, to their offspring (e.g., Alfred’s mother), or (3) the mothers in Beowulf. This small amount of scholarship on mothers reflects the scarcity of women who act as mothers in the corpus of Old English literature. In addition to their appearances in the Anglo- Saxon Chronicle and Beowulf, mothers and mothering emerge, however briefly, in other genres, from the leechbooks[6] to elegiac poetry. One thinks particularly of the desolate lover and mother in “Wulf and Eadwacer,” who must watch her “whelp” being taken into the woods.[7] The law codes reference mothering— especially in terms of inheritance[8]—as does poetry, in the Maxims[9] or in the poem Elene. Although their appearances are rare in the corpus of Old English literature, mothers do appear in a variety of genres and in a variety of ways, and their various presences can help us to understand the ways in which women and their bodies—particularly their maternal bodies—functioned and were perceived in contemporary society. By examining the invisible or unnatural bodies of monstrous mothers in Wonders of the East, then, we can expand traditional views of what it meant to be a woman and a mother in Anglo-Saxon England.

Wonders of the East depicts thirty-seven marvelous places and creatures, twelve of which are monstrous humans. Only two of them are designated as female.[10] We are told clearly that these monstrous humans are born in the marvelous East: Wonders uses and reuses the phrase, beoo akende (“there are born”)—and yet it is a text never cited in discussions of mothering. Acennan is verb that means “to bring forth, produce, beget, renew,” and it occurs 678 times in the corpus of Old English literature, with sixteen variant spellings, and it is used eighteen times in the Old English Wonders of the East.[11] While this is a relatively small percentage of total usage, it is notable that a text that takes up only nine folios in the Tiberius manuscript contains so many occurrences of the word. This is a text clearly concerned with reproduction, but one that is never discussed in this context, perhaps because what is giving birth and what is being born in Wonders are not human, but rather monstrous, bestial, hideous, alien, frightening. The Wonders of the East, part travel narrative, part bestiary, is a text full of monsters—monstrous beasts, monstrous plants and places, and monstrous humans. Monstrous humans, my focus in this essay, are those monsters that have distinctly humanoid characteristics and form, but who differ in visible and obvious ways from humans. While monstrosity can be a more metaphorical or psychological quality in modern usage, I argue that the clearest definition of a monster is based on physical difference. A monstrous body is visibly so and is constituted through lack, excess, or hybridity.[12] Certain monsters may lack body parts—legs, arms, or heads, such as Wonders’ blemmye, who have their faces in their chests. Other monsters are creatures of excess, such as various giants, who are significantly larger or taller than humans, or the men in Wonders who possess two faces on one head. Hybrid monsters possess the physical qualities of more than one kind of being; they may be hybrids of various animals, or of animals and humans, such as Wonders’ homodubii, who are human above the waist, and donkey below. The presence of animal parts on an otherwise recognizably human form seems not to have led to a monster being classified as an animal. Indeed, the Anglo-Saxon listing of monsters in the Liber Monstrorum carefully divides its monsters into three categories: monstrous men, monstrous beasts, and monstrous serpents.[13] This text demonstrates that those creatures that possess both animal and human features, such as fauns, sirens, hippocentaurs, and the cynocephali (conopoenae), are still considered human. Monstrous humans are not to be identified as animals; they are, rather, incomplete or over-determined humans. Therefore, the monstrous humans described and illustrated in Wonders are visibly monstrous through lack, excess, or hybridity, and we are told repeatedly that they are born in these exotic eastern regions, presumably to mothers as monstrous as they are.

While the language of the Wonders text articulates the genetic nature of monstrosity—as a “born” quality—as already noted, we rarely see those who give birth to children, monstrous or otherwise, in Anglo-Saxon literature. Dockray- Miller argues that many mothers in Anglo-Saxon literature have been occluded— obstructed or kept out of view—; she follows Allyson Newton, who claims “the maternal…is appropriated by processes of patriarchal continuance and paternal succession…that occlude the maternality upon which lineage and succession are dependent.”[14] Thus, women’s rightful places in lineage and succession have been closed off, blocked, and replaced by husbands and fathers. The maternal function of reproduction is assumed, but not represented. The same is true in Wonders, where only two female monsters are mentioned or drawn explicitly, even though all of the monstrous communities are perpetuated through reproduction. When they are told, for example, “There are people (men) born there who are fifteen feet tall,”[15] readers must deduce that the Old English word, men, refers to a community of monstrous people of both sexes. We, as readers, assume that these monstrous people get and beget children in the usual ways, despite their excessive height, or the fact that they have faces in their chests. While these monstrous mothers of Wonders seem to be occluded, both in the literary record and in subsequent scholarly conversation, they are also rendered invisible because their bodies, already so transgressive, are positively unthinkable in terms of pregnancy and birthing. A monster is a powerful symbol of aggression against the human, but a female monster presents another dilemma: as a monster, she might be an immediate physical threat, but as a woman, she should not be, although she might be threatening in other ways. Moreover, her generative power—her ability to procreate—renders her powerful and terrifying because she perpetuates the line of monsters. The monstrous woman indicates that perhaps all women might exceed the boundaries placed around them, as Kristeva notes “…it is always to be noticed that the attempt to establish a male, phallic power is vigorously threatened by the no less virulent power of the other sex, which is oppressed…That other sex, the feminine, becomes synonymous with a radical evil that is to be suppressed.”[16] The monstrous women of most of these communities, then, are suppressed and occluded in the service of establishing and promoting masculinity and patriarchal order. The presence of born male monsters, therefore, both indicates and occludes the mothers that produced them. These invisible mothers are the conduit through which monstrosity passes; they participate in an entirely different kind of succession that cannot be blocked completely by fathers, artists or authors. Their own physical monstrosity is written on the bodies of their monstrous offspring, even if they are written out of the text itself.

There has been virtually no discussion of maternity in the Wonders of the East—but not because the text occludes all of its women. Rather, we read over the top of those that are present in the text. Like passersby at a freak show,[17] we are distracted by the fascinating beings before our eyes, not really stopping to consider exactly how they got there. We read directly over the most perplexing of these monsters, the two female monsters, without recognizing the most monstrous thing about them. Scholars have read and reread these monstrous women—and they are identified explicitly as women (wif)—but none has ever asked: how indeed do communities of female monsters reproduce? While monstrous communities of people (designated by the Old English term, men) seem to be constituted by both men and women, allowing for familiar sexual reproduction, the same set of assumptions cannot stand for communities of monstrous women. Their monstrosity relies upon their sex and gender status, and therefore, by definition, men cannot be a part of their communities. Although motherhood is suggested and then occluded frequently in this text when we are told monsters are born in the East, such is not the case for the two female monsters of Wonders. Rather, I argue that their specific kinds of monstrosity rely on their possession of bodies that are both masculine and feminine, and indeed, on the very dangers that such hybrid bodies suggest. Although the text does not say so explicitly, it subtly suggests that, because there are no male members in these exclusively female communities, perhaps what is most monstrous about these women is that to become mothers, they do not require men.

Indeed, it is the sex and gender hybridity of these women that makes them monstrous and most dangerous. While most monstrous hybridity is human- animal hybridity, the collapse of two sexes into one body is perhaps even more troubling. As Jeffrey Jerome Cohen argues, “the monster is dangerous, a form suspended between forms that threatens to smash distinctions.”[18] While threatening to smash the distinction between man and animal is frightening, eliminating the distinction between male and female would lead to the collapse of the medieval social order. Ruth Mazzo Karras notes, “the binary opposition between men and women was extraordinarily strong in medieval society…The category [of woman] was lower in the hierarchy.”[19] As Karras demonstrates, the division between the sexes was clearly articulated, positing women as weak and passive, in both the social and sexual senses. To remove this distinction would radically reorganize society by reconfiguring the dynamics of power. Karras particularly considers the implications for gendered behavior, arguing that crossing gender lines did not change one’s sex: “Women who transgressed the expectations for their gender did not thereby become not-women; they became deviant women, and the same was true for men…A woman who played a masculine role in sex, or a man who played a feminine role, did transgress, but they did not thereby become a member of the opposite, or a third, gender.”[20] Therefore, crossing the lines of gender placed the transgressor in the role of an outsider, but it did not transform him or her into a member of the opposite sex. And yet the bodies of monstrous women in Wonders do more than transgress gender boundaries; they disrupt sexual categories because they possess the physical markers of both men and women. Their hybridity is not merely behavioral—it is marked on their bodies in ways that are impossible to ignore. Yet, while these male attributes appear on their bodies, the author still clearly categorizes them as women, wif, identifying the particular taxonomy of their monstrosity: that they exceed the boundaries not only of the human body, but of the female one. They are, then, identified linguistically as women who take on additional features; not as indistinguishable inter-sex hybrids.

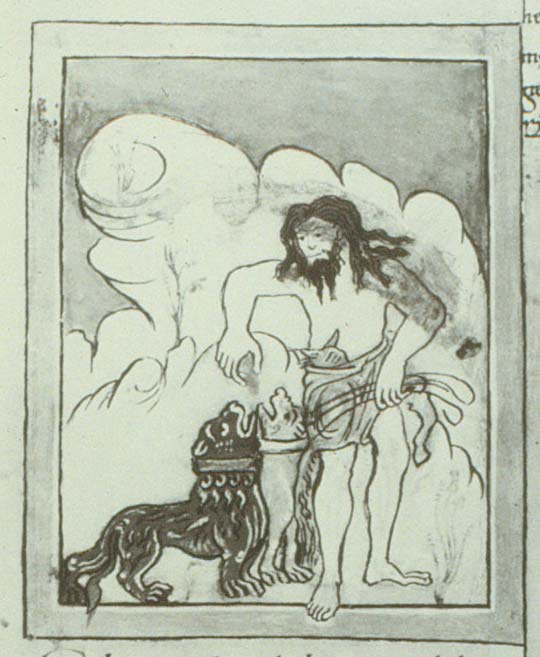

Fig. 1. Huntress, Wonders of the East, London, the British Library, MS Cotton Tiberius B.v., fol. 85r (detail) (© the British Library Board)

The first women mentioned in Wonders are the huntresses, although by looking at the image that accompanies their description in the Tiberius manuscript, we might not identify them as women (Figure 1). The author clearly points to their sex twice. First, he tells us that “Around those places, women are born.”[21] Instead of his typical formulation that employs the term men, (people), he clearly identifies this group as wif (female). Moreover, we are told that “they are called great huntresses.”[22] Huntigystran—huntresses—is a feminine form, and apparently the only feminine form of this word used in the corpus of Old English literature.[23] These women seem to be the only actual huntresses featured in Old English literature, a fact that emphasizes both their uniqueness and their gender transgression. The word, huntigystran, mimics their state of being, because it imposes the feminine ending on a masculine word, just as masculinity is imposed on a female body. The singularity of the term suggests the singularity of the habit; Anglo-Saxon women do not hunt, but monstrous women from the East do, and they do so with great skill. Their identifying quality is a gendered masculine behavior, but it is attached to bodies that although linguistically gendered female, appear to be very masculine.

If we look to the image from Tiberius, the best-illustrated of the three Anglo-Saxon manuscripts, feminine physical markers are in fact de-emphasized (Figure 1). The figure has long, scraggly hair and a similarly unkempt beard, which is unsurprising, as the author tells us “they have beards down to their breast.”[24] What is surprising is the completely naked and strikingly painted chest of the figure. Upon first glance, one might miss the detailed painting and see instead a flat-chested rather masculine-looking creature. However, upon a closer examination, one finds painted, very delicately in shades of white and palest pink, clearly feminine breasts. While figures of men in the manuscript frequently display pectoral markings and masculine nipples, in this image, the women’s breasts are clearly differentiated, but also indicated in a far more subtle way. In fact, in the published facsimiles of this image, available only in black-and-white, the breasts cannot be seen at all. Although the term breost in Old English is a gender-neutral term, the author has made it quite clear that this monstrous human is a woman. Her bare breasts, while not necessarily sexualized as they are in modern Western culture, convey her reproductive status. As Karras notes, “The female breast as depicted in medieval art may not have had the same sexual meanings as the breast today does, since it was used mainly to represent nurturing…, but motherhood in terms of the nurturing of children was inseparable from the bearing of those children, which was inseparable from the process of their conception. In all cases except the Virgin Mary, that process involved sexual intercourse.”[25] It is the artist who has depicted the monster in a largely masculine way, with large, square shoulders, a thick neck, small eyes with thick brows, and rough-looking hair and beard set deliberately against her pale pink breasts. If we look to the other manuscripts’ images, in particular the later Bodley

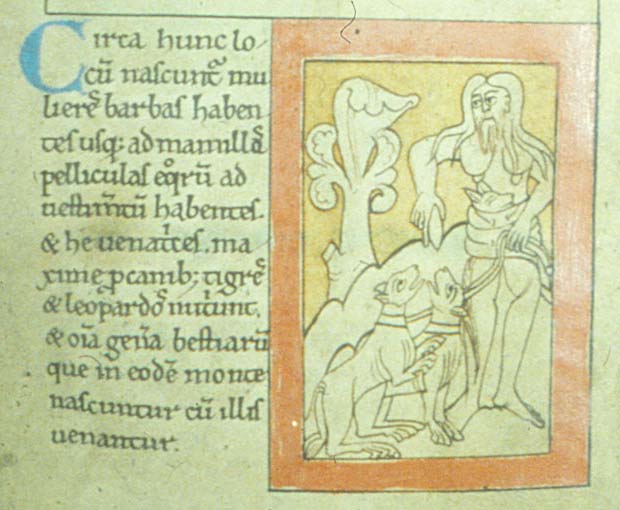

illustration, the artist approaches the juxtaposition with less subtlety (Figure 2). The masculine hair and beard, and indeed facial features, exist in unflinching contrast with heavy breasts and exaggerated nipples. These images reveal not only different attitudes toward monstrosity and bodies, but also the crux of this creature’s status as a monster: she is a monster of sexual hybridity. The artistic variations demonstrate the difficulty of rendering this particular kind of monstrous and female body.

Fig. 2. Huntress, Wonders of the East, Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Bodley 614, fol. 44v (detail) (© the Bodleian Library, the University of Oxford)

Just as the huntresses combine both masculine and feminine physical features, so too do they exhibit behaviors that are an amalgamation of traditionally male and female activities. We learn that they make their tunics from “horse’s hide” suggesting the feminine labor of making clothing, although the image shows their apparel to be very masculine, even baring the torso.[26] This half-covered state indicates both their civilized status, in that they wear clothes at all, and also their monstrosity, in that they are not dressed like any fully human figures depicted in the manuscript.[27] It also reveals their sex and gender status, as they dress like (relatively uncivilized) men and expose their female breasts to open view. Their skill as huntresses is emphasized by their reputation among surrounding peoples, who primarily identify them through this typically male ability. Similarly, their nurturing of wild animals demonstrates both masculine and feminine qualities: “Instead of dogs, they bring up tigers and leopards, that are the fiercest beasts, and they hunt all kinds of wild beasts that are born on the mountain.”[28] While the huntresses enact the medieval male skill of the hunt and thus the kill, they also have the ability to fedan, which carries the meaning of “to feed” but also to “nourish, sustain, foster, bring up” and even “bear, bring forth, produce.”[29] It seems reasonably clear that the women are not giving birth to the tigers and leopards, but they do more than simply feed them—they nurture and raise them. Even though medieval men probably raised their hunting dogs in the way these women raise their tigers, the use of a word that is so bound to women’s work is striking in this context.[30]The huntresses take on masculine habits and carry them to excess, in that they work with and hunt animals fiercer and more exotic than those pursued by most medieval men. However, they also exhibit the stereotypically feminine ability to raise or nurture young, a quality that implies the possibility of motherhood and reproduction, and that is emphasized by the productive and nurturing potential of the breasts. These huntresses seem to distort all things civilized, especially in the arena of the hunt: women replace men, beasts replace dogs, and horses are used as clothing instead of mounts.[31] However, the huntresses are not monstrous simply because they upset these conventions. They are less frightening for their monstrous behavior (usurping masculine work), than for the place from which this behavior originates—their monstrous bodies (usurping masculine physical features). As the descriptions and images of the huntresses attest, the anonymous narrator and artists blur the line between masculine and feminine qualities. The ultimate cultural threat posed by the huntresses is their ability to bear the identities of both men and women.

What makes the huntress a monster, in other words, is her juxtaposition of feminine and masculine physical characteristics and behaviors. She is not a creature of lack, like the blemmyes, men with no heads and faces in their chests; nor is she simply a creature of excess, like the people who are fifteen feet tall or the men with fan-like ears in which they can sleep. She is a sex-hybrid. She maintains female physical traits, including the breasts featured in all of the images, but also possesses the masculine beard. What is monstrous and frightening about this creature is not that she seems to be hurting people, as other monsters do, but that she violates categories that define the cultural community. She is female, but not just female—and it is this that makes her monstrous. Moreover, this form of monstrosity is inherently feminine; men cannot and do not exist in this community, for a male of this species would not be a monster, but merely a bearded hunter.

Since what is more precisely monstrous about this race of textually-identified women is the blurring of the categories of male and female, it is untenable that their imaginary community includes both men and women as conventionally understood in medieval culture. The author has told us that this race of monster is comprised of wif (women), not of men (people). They are, at the most basic level, female, although they simultaneously possess male features. Therefore, as readers, we face a conundrum. We are told explicitly that this race of women is born here—but to whom are they born? In what way are they conceived? The author of Mandeville’s Travels, a much later travel narrative, explains how the Amazons, another all-female race, meet men at the borders of their territories to conceive children,[32] but the author of Wonders makes no mention of reproductive practices. He seems to care very little about the biological impossibility of same- or single-sex reproduction, but instead fixates on the visible categories of difference from the human. However, it is precisely this reproductive mystery that marks these monstrous women as indelibly Other. They are born on the mountain, but they seem to be engendered by only one parent—the mother. What is necessary for this community to be monstrous— their hybrid sexual identity—indicates that there can be no fully male members of the community. Therefore reproduction in this place, which results in the continuation of the community of this particular kind of monster, must occur without males. This ability elevates the monstrous nature of these women as they push the boundaries of sex and indeed humanity even further. The bearded huntress must be what Barbara Creed terms an ‘archaic mother,’ “the parthenogenetic mother, the mother as primordial abyss, the point of origin and of end.”[33] These huntress’ bodies are terrifying because they complicate the distinction between male and female, and co-opt masculine potency in their autonomous reproduction of monstrous women. They act as single points of origin, ones that are identified by the author as primarily female, but also monstrous because of their possession of male appendages. Therefore, in these bearded women we find a variation of the Anglo-Saxon mother as one who is self- sufficient and autonomous—albeit one whose body and behaviors are hybrid.

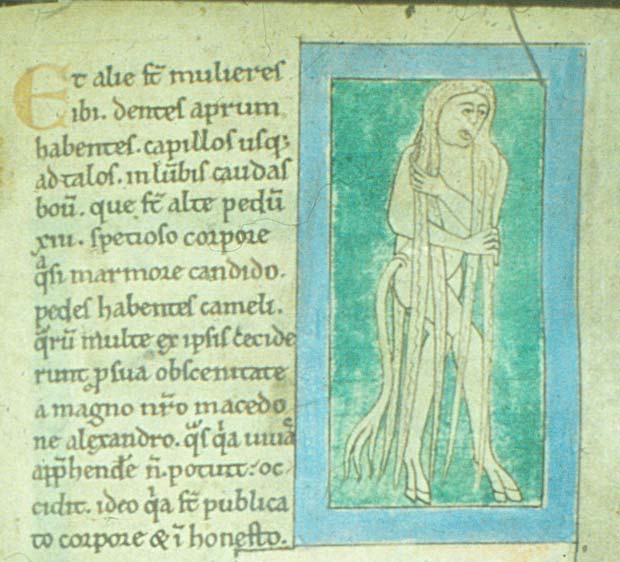

Hybridity also characterizes the bodies of the second group of monstrous women in Wonders of the East, not named by the author but identified by their tusks and tails. While hybrid sex is not the primary marker of their monstrosity, they also transgress human boundaries of sex and gender in a way that affects their ability to reproduce. They are beast-human hybrids. They possess “boar’s tusks and hair down to their heels and ox-tails on their loins. These women are thirteen feet tall and their bodies are of the whiteness of marble. And they have camel’s feet and boar’s teeth.”[34] They are monstrous because their bodies are both human and bestial; aside from their camel-feet, most of their animal parts are protrusions—tusks, tails, and teeth. The length of their hair and the whiteness of their skin would seem to signify beauty—albeit beauty of an excessive and perhaps ethereal type—rather than monstrosity. Indeed, in looking at the Tiberius image (Figure 3), this female is quite physically attractive, aside from her animal parts. Her facial features are far more delicate than those of the male monsters in the manuscript, and her body is posed in a way that conceals her secondary sex characteristics but reveals her femininity. Even the tiny tusk on her right upper lip is dainty, perhaps a monstrous version of the Marilyn-Monroe- mole.

Like the huntresses with their beards, the tusked women’s bodies take on a masculine physical signifier. In this case, it is their tails, evident in all three images as well as in the written description.[35] The reader is told that “They have boar’s tusks and hair down to their heels, and ox-tails on their loins. These women are thirteen feet tall and their bodies are in the whiteness of marble, and they have camel’s feet and boar’s teeth.”[36] While this is mainly a list of parts taken from various animals and applied to the body of a woman, it is not the bestial nature of the woman’s body that is most troubling. Instead, the danger of her body is revealed in the relationship between the physiological term, lendenu, given as the location of the tail, and the illuminations of this figure, which reveal the artists’ anxiety about this feature. The writer tells us that the women have “ox-tails on their loins,”[37] yet the artists draw these tails on their posteriors (Figures 3, 4, 5). If the tails were located in the expected place, the author need not have mentioned this, but because they are not, he had to specify their anatomical location. Moreover, the Anglo-Saxon word, lendenu, and the parallel Latin term, lumbi, used in both the Tiberius and Bodley manuscripts, are words that possess a sexual connotation. Old English dictionaries define lendenu generically as ‘loins,’ but the Oxford Latin Dictionary defines lumbus as “the part of the body about the hips, the loins; the seat of sexual excitement.”[38] Although this is a reasonably common term in Latin, it occurs rarely in Old English and is a strange word to find in a travel narrative.[39] To possess this phallic protrusion in a location affiliated with sexual excitement makes these women a kind of sexual hybrid. It also makes them so transgressive that the artists primly move their tails to a more familiar spot on their monstrous bodies. In so doing, the artists reaffirm their femininity and gloss over their hermaphroditic qualities.

Fig. 3. Tusked woman, The Wonders of the East, London, British Library, MS Cotton Tiberius B.v., fol. 85r (detail) (© the British Library Board)

Fig. 4. Tusked woman, The Wonders of the East, Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Bodley 614, fol. 45r (detail) (© the Bodleian Library, the University of Oxford)

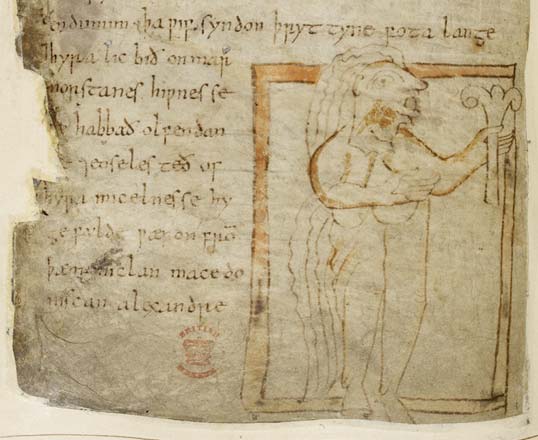

Fig. 5. Tusked woman, The Wonders of the East, London, British Library, MS Cotton Vitellius A.xv., fol. 105v (detail) (© the British Library Board)

Although lendenu might very well be a reference to a specific body part, it seems more likely that, in the Wonders text, lendenu as a more general reference to that part of the body is meant to invoke lust.[40] While Ælfric generally urges his readers to gird their loins, these female monsters have ox-tails on them. Therefore, rather than being carefully contained, the loins of the tusked women extrude in the form of ox-tails, a strangely bestialized and non-productive protrusion. Yet no artist draws the tail in the phallic position that the text suggests. As in the Tiberius manuscript, the Bodley artist locates the tail at the base of the spine, but makes few adjustments to the Tiberius arrangement (Figures 3, 4). In the Vitellius image, we can see the curve of the buttock in profile, but the figure’s tail seems to be coming out of the side of her leg, perilously close to her groin (Figure 5). Her torso seems to be an amalgamation of sexual and animal parts. Whatever lack of perspectival accuracy modern viewers might assume of the Vitellius artist, perhaps this image with its oddly placed tail is truer to the spirit of the description. The figure is a body of both human and animal excess, not a lovely human body that merely has supplementary animal parts. It is not just the animal elements that make this creature monstrous, but the combination of her excesses.

According to the accompanying text, the tusked women are the only monsters exterminated by human travelers. Even the monsters known as the Donestre, who deceive and consume passing travelers, are allowed to continue living;[41] and yet these females, who do no harm to humans, are killed by Alexander the Great. We are told, “Because of their uncleanness they were killed by Alexander the Great of Macedon. He killed them because he could not capture them alive, because they have offensive and disgusting bodies.”[42] Their bodies are “offensive” and “disgusting” not because they are animal-human hybrids, like many of the other monsters in Wonders. They are killed because they are a far more awful hybrid—a female-male one. In contrast to the bearded huntresses, they seem to be both more attractive, possessed as they are of more feminine qualities in form and feature, but also more phallic. The tusked women are simultaneously beautiful and feminine, through the rich curtain of their hair; and masculine, in their phallic excess of both tusks and tails. They seem to inspire both desire and repulsion: Alexander desires to capture them and fails, so therefore he must kill them because their bodies are “unclean,” “offensive,” and “disgusting.”[43] In fact, the Latin text uses the term obscenitate, which means “impure.”[44] The bodies of these monstrous women are abject, a construction through which, as Creed notes, “an opposition is drawn between the impure fertile (female) body and the pure speech associated with the symbolic (male) body.”[45] The violence inflicted upon the tusked women, but not on the huntresses, serves to say that a facial beard is one thing, but a genital tail is another entirely: the tusked women threaten not to elide important cultural categories, but literally to penetrate men’s—and perhaps women’s—bodies. Thus, their bodies are not only hybrid but also tainted or troubling in sexual and biological ways.[46]

Alexander solves the problems of these women by killing them for possessing bodies that exceed the boundaries of social and sexual decency, whereas artists neutralize them by revising the images. The authors and artists both warn women to stay in their place, a place that, according to Karras, is characterized by passivity: “One thing we can say with some certainty…is that medieval people would have understood marital sex as something the husband did to the wife.”[47] The woman does not act, but instead is the passive recipient of the sexual actions of the man. If a woman were to be the actor and the man, the recipient, this would be a reversal of gender roles, and would effectively gender the man feminine.[48] As Karras argues, “Women’s sexuality threatened medieval men in many ways: they might be temptresses and lure men into fornication or worse sins, they might behave in masculine ways with each other and so usurp male gender privilege, or they might use sexuality in other ways to control men.”[49] The tusked women embody all three of these qualities. I posit, based on the narrative constructed by the Wonders author, that they lure Alexander and direct his behavior (he must either have them or destroy them), but they threaten to do even more than act in masculine ways with one another: they threaten to act in masculine ways with Alexander, who desires them. The revised image of this monster secures women in their (passive) position, but the traces of their sexed and sexual monstrosity reveal the threat to social and sexual phallic order that these monstrous women, and perhaps even all women, might embody. For if a monstrous woman can become active and penetrating, then a human one might be able to do the same, either literally or symbolically.

As with the huntresses, male members of the tusked species do not exist. The text emphatically declares this a community of women by giving them their own section and illustration, beginning with the phrase “Then there are other women.”[50]) Even hypothetically, male monsters of the tusked sort would seem far less monstrous than their female counterparts. Not only would they be less dangerously appealing to male travelers like the presumably heterosexual Alexander, their phallic protrusions would merely compound their excessive masculinity rather than juxtapose it with their femininity. The tusked women, however, are monstrous precisely because they are simultaneously female and male. They exist as a community of isolated women who clearly are able to reproduce themselves. The presence of the phallic tail, however mediated by artists it might be, imbues these women with a level of masculinity and indicates their potency. They have usurped both the male body, in possessing a kind of phallus, and the male function, in seeming to engender children without requiring men to do so. The tusked and tailed woman, then, is what Marcia Ian calls the ‘phallic mother,’ “a grown woman with breasts and a penis,” who “represents the absolute power of the female as autonomous and self- sufficient.”[51] She does not sacrifice her female nature in taking up the phallus, but instead threatens the patriarchal order as well as the integrity of the male body by maintaining a body that is at once feminine and phallic.[52] She serves as an abject figure, in Kristevan terms—a woman, especially a mother, whose body must be rejected and excluded in order to establish patriarchal and patrilineal identity. As abject, her body is figured as defiled or polluted as a means to dominate it.[53] Thus, the tusked and tailed women possess monstrous and hybrid bodies that supersede men and it is this that makes them so obscene, so unclean, so revolting to Alexander that he must take action against them. Ultimately, however, it is the reproductive potential of their hybrid bodies—their transgressive maternity—that makes them most monstrous.

While the author of Wonders of the East does not explicitly paint the huntresses and the tusked women as hermaphroditic or auto-generative, he leaves the door open for speculation. Both sets of monstrous women possess masculine attributes that can be perceived as phallic. The huntresses have beards, which are equated with masculinity in some medieval texts, and which are particularly associated with male monstrosity in the figure of the giant or the wild man. If to remove a man’s beard, as we can see in texts such as the later Alliterative Morte Arthure, is emasculating and indeed castrating,[54] then to possess a beard is to possess a kind of phallus. More obviously, the tusked women possess tails that protrude from their loins, their genital region. Although the artists refuse to draw them this way, we can imagine that this phallic tail might impugn and belittle Alexander’s own masculinity. The only two monstrous women pictured and described in Wonders must possess a kind of monstrosity not applicable to male monsters. They exhibit physical qualities that only monstrous women can possess, qualities to do with sex and sexuality which are bound up with reproduction. The representation of these phallic women is designed to incorporate “fear, desire, anxiety, and fantasy”;[55] they invite desire, but also require censure. As Creed argues, “Patriarchal ideology works to curb the power of the mother, and by extension all women, by controlling women’s desire through a series of repressive practices which deny her autonomy over her own body.”[56] By representing, but also controlling the ways in which these monstrous women’s bodies are depicted, the author and artists of Wonders of the East confirm the male hierarchy. And yet, the power of female monstrosity permeates the text through the fissure of maternity. While female monsters are largely invisible in the wondrous East, they nevertheless must exist in all of the monstrous communities, since all these monsters are “born” here. Moreover, the communities of monsters that are identified specifically as female must be exclusively female. Therefore, although we do not see it, we must assume they are mothers, and we might suspect they act also as fathers.

In the Wonders of the East, the specter of maternity is raised frequently but it is never addressed. Mothers in Wonders are invisible; they clearly must exist, but they are never seen. Maybe this invisibility reflects a more urgent cultural desire to occlude Anglo-Saxon mothers. Or perhaps mothering itself was viewed as monstrous: the female body does things that are at once profoundly natural and frighteningly superhuman. As Creed argues, “the act of birth is grotesque because the body’s surface is no longer closed, smooth and intact— rather the body looks as if it may tear apart, open out, reveal its innermost depths. It is this aspect of the pregnant body—loss of boundaries—that the horror film emphasizes in its representation of the monstrous.”[57] If, as Cohen has argued, monsters disrupt boundaries, then the pregnant body itself is monstrous, interrupting the distinction between internal and external, individual and mutual. To be a mother is to have a strong connection to a child above all else, a quality that is deeply dangerous in Anglo-Saxon England, where social bonds and peace-weaving structure uphold the patriarchal order. The maternal body is, for a time, a double thing, a hybrid that contains two beings inside one skin. It is plastic, changing, unstable, always threatening to open out, tear itself open, and reveal itself. This is the danger of the female body. It is a body capable of wondrous changes, and it is not entirely subject to the patriarchy that contains and controls it. The body of the mother remains invisible in medieval literature because it is immensely powerful and substantively ungovernable; the only way to co-opt it is through representation, in the writing of genealogies that leave out mothers or in the drawing of monstrous forms that are borne to invisible women. The maternal body is “desirable and terrifying, nourishing and murderous, fascinating and abject.”[58] It is double, and its procreative abilities—whether parthenogenetic or traditional—render it monstrous and marvelous. When even human mothers are occluded, we cannot be surprised that monstrous ones remain invisible. Yet it is these monstrous mothers, females whose bodies exceed the boundaries of nature and society, who reveal the presence and potential of the medieval human mother.

References

| ↑1 | Mary Dockray-Miller. Motherhood and Mothering in Anglo-Saxon England (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000), xiii. In material culture, too, women’s names rarely appear on items either owned or given by them. See Gale Owen-Crocker, “Anglo-Saxon Women; the Art of Concealment,” in Leeds Studies in English 33 (2002): 31-51. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. Trans. Leon S. Roudiez (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982), 77. |

| ↑3 | Dockray-Miller, Motherhood. The following three categories, though representative of the larger field of study, directly follow Dockray-Miller’s organizational schema. |

| ↑4 | See Gillian Overing and Clare Lees, “Birthing Bishops and Fathering Poets: Bede, Hild, and the Relations of Cultural Production,” Exemplaria 6 (1994): 35-66. Dockray-Miller notes that “there is more textual evidence available about spiritual motherhood than about actual motherhood, an imbalance that likely accounts for the usual critical focus on spiritual motherhood” (Motherhood, 2). https://doi.org/10.1179/104125794790510753 |

| ↑5 | See Dockray-Miller, Motherhood, chapter three, “The Maternal Genealogy of Æoelflæd, Lady of the Mercians.” |

| ↑6 | See R. A. Buck, “Women and Language in the Anglo-Saxon Leechbooks,” Women and Language 23 (2000): 41-50; and Marijane Osborn, “Anglo-Saxon Ethnobotany: Women’s Reproductive Medicine in Leechbook III,” in Health and Healing from the Medieval Garden, ed. Peter Dendell and Alan Touwaide (Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2008), 145-61. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvc16gkc.14 |

| ↑7 | “Uncerne eargne hwelp bireo wulf to wuda” (16b-17a); ed. Bruce Mitchell and Fred Robinson, “Wulf and Eadwacer,” in A Guide to Old English, 6th ed. (Oxford: Blackwell, 2001), 297-299. |

| ↑8 | For a focused listing of law-codes related to issues of women and marriage, see Love, Sex and Marriage in the Middle Ages: a Sourcebook, ed. Conor McCarthy (London: Routledge, 2004), 97-107. |

| ↑9 | As Robin Smith points out regarding “Maxims I,” “The poem gives utterance to the poet’s view of the way things ought to be; a well-ordered world demanded that the wife attend to her husband’s physical and emotional needs. The children were of no concern to this poet of wisdom…[who] later remarks that a woman belongs at her embroidery rather than outside her home…As for the children, it is evident that they were to be left to their own devices at least at the times when the husband returned to the hearth” (Robin Smith, “Anglo-Saxon Maternal Ties,” in This Noble Craft: Proceedings of the Xth Research Symposium of the Dutch and Belgian University Teachers of Old and Middle English and Historical Linguistics, Utrecht, 19-20 January, 1989, ed. Erik Kooper (Amstedam: Rodopi, 1991), 106-17 (at 109). https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004490208_008 |

| ↑10 | Wonders of the East exists in three Anglo-Saxon manuscripts: (1) London, British Library, MS Cotton Vitellius A.xv., c. 1000, (2) London, British Library, MS Cotton Tiberius B.v., 11th c., and (3) Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Bodley 614, 12th c. The following editions have been invaluable: An Eleventh Century Anglo-Saxon Miscellany, ed. P. McGurk, et al. (Copenhagen: Rosenkilder and Bagger, 1983); Montague Rhodes James, Marvels of the East (Oxford: Roxburghe Club, 1929); Three Old English Prose Texts in MS Cotton Vitellius A.xv, ed. Stanley Rypins, Early English Text Society, o.s. 161 (London: Oxford University Press, 1924); Andy Orchard, Pride and Prodigies: Studies in the Monsters of the Beowulf-Manuscript (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1995); and Electronic Beowulf (version 2.0), ed. Kevin Kiernan (London, British Library, 2004). The written descriptions of the wonders in Tiberius, Bodley, and Vitelllius are accompanied by illustrations. While there is very little variation in the content of the written texts in the three manuscripts, in Latin or Old English—although, as Asa Mittman notes, there is an “expansion of the text through the inclusion of several additional ‘marvels’ in each subsequent version” as well as some other minor changes (Asa Simon Mittman, Maps and Monsters in Medieval England [New York: Routledge, 2006], 69, 77)—the illustrations do vary in significant ways. The Tiberius descriptions are written in both Old English and Latin, while Vitellius uses only Old English, and Bodley, only Latin. I quote hereafter only the Old English, although I occasionally examine the Latin diction in order to clarify or to interrogate certain Old English terms. The Tiberius manuscript illustrates thirty-seven marvels, while Bodley includes forty-nine images, and Vitellius, only thirty-two. I use Tiberius as my primary text, although I also consider images and creatures from Bodley and Vitellius. Citations of the text are taken from Andy Orchard’s edition. For more on the historical context of the three manuscripts, see Mittman, Maps and Monsters, esp. 69-78. On their texts and images, see the articles by Susan Kim, Asa Mittman, and Rosalyn Saunders in this volume. |

| ↑11 | From the University of Toronto’s Dictionary of Old English online corpus: http://ets.umdl.umich.edu.proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/o/oec/ (accessed May 2008). |

| ↑12 | I argue this point in my book, titled Monsters, Gender and Sexuality in Medieval English Literature (Boydell and Brewer, 2010). While a human might behave in a way perceived to be monstrous, that behavior is a temporary quality that can be reformed. However, a monster that is physically monstrous must remain a monster. This is not a social quality, but a physical one. For further discussion of hybridity, see Bruno Roy, “En Marge du monde connu: les races de monstres,” in Aspects de la Marginalité au Moyen Age, ed. Guy-H. Alland, et al. (Montreal: L’Aurore, 1975), 71-81; and David Williams, Deformed Discourse: The Function of the Monster in Medieval Thought and Literature (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1996). Williams follows Isidore, using the human form as the template against which to understand monstrosity (Deformed Discourse, 108), and offers a taxonomy of monstrosity more detailed than my own, one intended to illustrate frequently represented groups, while mine attempts to describe ideological categories of difference. |

| ↑13 | Orchard, Pride and Prodigies, 294-95. |

| ↑14 | Allyson Newton, “The Occlusion of Maternity in Chaucer’s Clerk’s Tale,” in Medieval Mothering, ed. John Carmi Parsons and Bonnie Wheeler (New York: Garland, 1996), 63. |

| ↑15 | “Dær beoo akende men, oa beoo fiftyne fota lange…” (Orchard, Pride and Prodigies, 190). |

| ↑16 | Kristeva, Powers of Horror, 70. |

| ↑17 | While ‘freak show’ is a generally offensive term, it is also one that has been reappropriated by certain communities and scholars, as is argued in Rosemarie Thompson’s collection, Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body (New York: New York University Press, 1996). |

| ↑18 | Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, “Monster Culture,” in Monster Theory: Reading Culture, ed. Jeffrey Jerome Cohen (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996), 3-25; at 6. |

| ↑19 | Ruth Mazzo Karras, Sexuality in Medieval Europe: Doing Unto Others (New York: Routledge, 2005), 5. |

| ↑20 | Ibid., 5. On the concept of a ‘third sex’ in Anglo-Saxon art and thought, see Madeline Caviness, “Anglo- Saxon Women, Norman Knights and a ‘Third Sex’ in the Bayeux Embroidery,” in The Bayeux Tapestry: New Interpretations, ed. Martin Foys, et al. (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2009). 85-118. |

| ↑21 | “Ymb pa stowe beoo wif akenned” (Orchard, Pride and Prodigies, 198). |

| ↑22 | “Pa syndan huntigystran swioe genemde” (Orchard, Pride and Prodigies, 198). |

| ↑23 | In a brief search of the Dictionary of Old English online corpus (as in n. 11), this spelling is unique. This term, with an alternate spelling, may appear elsewhere, but seems only to be used as a gloss in a vocabulary, rather than refer to an actual huntress. |

| ↑24 | “oa habbao beardas swa side oo heora breost” (Orchard, Pride and Prodigies, 198). |

| ↑25 | Karras, Sexuality in Medieval Europe, 152. |

| ↑26 | “horses hyda hi habbao him to hrægle gedon,” (Orchard, Pride and Prodigies, 198). The images in Tiberius and Bodley show us that their tanning and sewing skills leave much to be desired, as the heads are still attached to their skirts and the hems appear uneven and unfinished. |

| ↑27 | On monstrosity and clothing, see the article by Debra Higgs Strickland in this volume. |

| ↑28 | “fore hundum tigras 7 leopardos pæt hi fedao pæt synda oa kenestan deor. 7 ealra oæra wildeora kynn, 7 ealra oæra wildeora kynn, pæra pe on pære dune akenda beoo, pæt gehuntigao” (Orchard, Pride and Prodigies, 198). |

| ↑29 | An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary based on the Manuscript Collections of the Late Joseph Bosworth, edited and enlarged by T. Northcote Toller, ed. Joseph Bosworth and T. Northcote Toller (London: Oxford University Press, 1972). |

| ↑30 | Trained hunting dogs were of greater value, as is evident in the Anglo-Saxon lawcodes of Alfred, which list a higher penalty for harming a trained dog than for harming an untrained one. Moreover, hunting dogs often lived more luxurious lives than peasants. See Richard Almond, Medieval Hunting (Stroud: Sutton, 2003); and John Cummins, The Hound and the Hawk: The Art of Medieval Hunting (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1988). |

| ↑31 | The killing of horses for meat would have been a particularly taboo practice in late Christian Anglo- Saxon England, as the eating of horseflesh was associated with paganism (although there is evidence for the consumption of horseflesh at least until the eighth century). On horses in Anglo-Saxon culture, see J.M. Bond, “Burnt Offerings: Animal Bone in Anglo-Saxon Cremations,” World Archaeology 28.1 (1996): 76-88. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.1996.9980332 |

| ↑32 | The Defective Version of Mandeville’s Travels, ed. M. C. Seymour (Early English Text Society, n.s. 319) (London: Oxford University Press, 2002, 68-69): “And whanne pei wole haue ony man to lye by hem, pei sende for hem into a cuntre pat is nere to here lond, and pe men bep pere viii dayes oper as longe as pe wymmen wole and penne pei gop ayen.” (“And when they wish to have any man lie by them, they send for them into a country that is near to their land and the man is there eight days or as long as the women wish and then they go again.”) See also Ilse Kirk, “Images of Amazons: Marriage and Matriarchy,” in Images of Women in Peace and War: Cross-Cultural and Historical Perspectives, ed. Sharon MacDonald, Pat Holden, and Shirley Ardener (London: Macmillan, 1987), 27-39. |

| ↑33 | Barbara Creed, The Monstrous Feminine: Film, Feminism and Psychoanalysis (London: Routledge, 1993), 17. |

| ↑34 | “eoferes tucxas 7 feax oo helan side, 7 on lendenum oxen tægl. Pa wif wyndon oreotyne fota lange 7 heora lic bio on marmorstanes hwitnysse. 7 hi habbao olfenda fet 7 eoferes teo” (Orchard, Pride and Prodigies, 200). |

| ↑35 | The equivalent of tail in the Latin description is caudas, a term that can also be used as a euphemism for the phallus. See Oxford Latin Dictionary, ed. P. G. W. Glare (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1983). |

| ↑36 | “oa habbao eoferes tucxas 7 feax oo helan side, 7 on lendenum oxan tægl. Pa wif syndon oreotyne fota lange 7 heora lic bio on marmorstanes hwitnysse. 7 hi habbao olfenda fet 7 eoferes teo” (Orchard, Pride and Prodigies, 200). |

| ↑37 | “on lendenum oxen tægl” (Orchard, Pride and Prodigies, 200). |

| ↑38 | Oxford Latin Dictionary, 1049. |

| ↑39 | Lendenu occurs primarily in religious texts: Ælfric’s homilies, a few passages of Scripture, and one saint’s life. It appears only twice in law codes but is used repeatedly in medical texts. I argue this point in greater detail in Monsters, Gender, and Sexuality. |

| ↑40 | The medical texts that use this term are Leechbooks I and II, usually in a listing of various body parts. |

| ↑41 | On the Donestre, see the article by Rosalyn Saunders in this volume. |

| ↑42 | “For heora unclennesse hie gefelde wurdon fram oam mycclan macedoniscan Alexandre. Pa he hi lifiende gefon ne mihte pa acwealde he hi for oam hi syndon æwisce on lichoman 7 unweoroe” (Orchard, Pride and Prodigies, 200). |

| ↑43 | Orchard (Pride and Prodigies, 200) notes that unclennesse is used in the Bodley text, but both Tiberius and Vitellius use a form of mycelnysse [greatness]. He maintains the use of “uncleanness” in his translated version, probably because the Latin version uses the term obscenitate (p. 180). |

| ↑44 | Orchard, Pride and Prodigies, 180. |

| ↑45 | Creed, Monstrous Feminine, 25. |

| ↑46 | One might consider these women ‘impure’ because they are not purely human. However, so many other monsters in this manuscript possess animal-human hybridity, and yet Alexander feels no need to kill them or to call them impure. Therefore, impurity here seems to refer to something beyond their mixture of human and animal parts. |

| ↑47 | Karras, Sexuality in Medieval Europe, 85. This imperative of male authority over and domination of the female body in a sexual sense is reaffirmed in Sarah Salih, Anke Bernau, and Ruth Evans, “Introduction: Virginities and Virginity Studies,” in Medieval Virginities, ed. Anke Bernau, Sarah Salih, and Ruth Evans (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2003), 1-13. They argue: “The virgin is constructed with reference to the monster: according to Tertullian, the virgin woman who evades masculine control is ‘a third generic class, some monstrosity with a head of its own.’ This aspect of virginity is highlighted in the deliberate ambiguity of titles such as Ravishing Maidens and Menacing Virgins: in so far as virginity is monstrous, it challenges order and hierarchy” (p. 6). |

| ↑48 | Karras, Sexuality in Medieval Europe, 23. |

| ↑49 | Ibid., 116. |

| ↑50 | “Donne sindon oore wif…” (Orchard, Pride and Prodigies, 200 |

| ↑51 | Marcia Ian, Remembering the Phallic Mother: Psychoanalysis, Modernism and the Fetish (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1996), 1, 8. |

| ↑52 | Ian seeks to deconstruct the concept of the phallic mother as one that is culturally and socially constructed. |

| ↑53 | Kristeva, Powers of Horror, 17, 70. |

| ↑54 | For example, see Jeff Westover, “Arthur’s End: The King’s Emasculation in the Alliterative Morte Arthure,” The Chaucer Review 32.3 (1998): 310-24. See also Anne Clark Bartlett, “Cracking the Penile Code: Reading Gender and Conquest in the Alliterative Morte Arthure,” Arthuriana 8.2 (1998): 56-76. See Cohen’s “Medieval Masculinities: Heroism, Sanctity and Gender,” Inscripta (http://www8.georgetown.edu/departments/medieval/labyrinth/e-center/interscripta/mm.html, 1996; accessed 14 July 2009. https://doi.org/10.1353/art.1998.0014) where he points to this practice in Sir Ferumbras and The Siege of Jerusalem, as well as to Chaucer’s Pardoner’s much-contested lack of a beard. See also Elizabeth F. Urquhart, “Hair and Masculinity in the Alliterative Morte Arthure,” (M.A. thesis, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, 2006); available online: http://libres.uncg.edu/edocs/etd/1258/umi-uncg-1258.pdf; accessed 14 July 2009). She writes: “By the time the Alliterative Morte Arthure was written, the historical significance of the beard in law and society was well established. A powerful marker, the beard was a recognized indicator of social status, physical maturity, and masculinity, prevailing even over material wealth when it came to a man’s masculinity and reputation” (12). See also Robert Bartlett, “Symbolic Meanings of Hair in the Middle Ages,” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 4 (1994): 43-60. Bartlett argues for symbolic understandings of hair that are specific to their context, but he also clearly notes: “In the populations discussed here, those of medieval Europe, the most important biological differentia were that adults and not children had body hair and that only adult males had facial hair” (p. 43). https://doi.org/10.2307/3679214 |

| ↑55 | Cohen, “Monster Culture,” 4. |

| ↑56 | Creed, Monstrous Feminine, 162. |

| ↑57 | Ibid., 58. |

| ↑58 | Kristeva, Powers of Horror, 54. |