Linda Seidel • University of Chicago

Recommended citation: Linda Seidel, “Adam and Eve: Shameless First Couple of the Ghent Altarpiece,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 1 (2008). https://doi.org/10.61302/RLZJ2460.

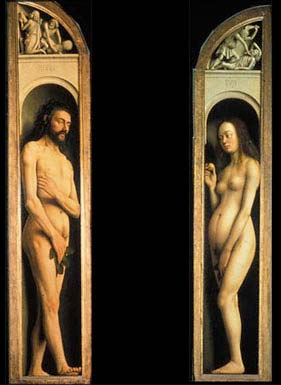

Jan van Eyck’s depictions of Adam and Eve were marveled at for their lifelikeness before the close of the century in which they were painted, and on subsequent occasions in the following hundred years (Figure 1). Yet interest in their astonishingly realistic anatomy did not engage sustained discussion until the twentieth century, testimony to both the complex history the Ghent Altarpiece experienced during the intervening period and the figures’ particular fall from grace.[1] Documents report that the Altarpiece, which from the outset was on restricted view in the private chapel at the Church of St. John for which it had been made, was subject to additional events that impeded its accessibility. These included wars, during which the Altarpiece was dismembered and hidden, and changes in taste that resulted in the removal of the Adam and Eve and their replacement by properly clothed copies (Figure 2).[2] Only in the twentieth century, when Jan’s Adam and Eve were placed on public view in independent exhibitions and then returned to their original positions on the reconstructed Altarpiece, did conversation about their remarkable bodies emerge as a topic in the scholarly literature.

Fig. 1. Adam and Eve, end panels from the upper register of the inner wings, Ghent Altarpiece, St. Bavo’s Cathedral, Ghent.

But even then, discussion regarding their depictions receded behind art historical interest in other issues du jour. Engagement with the Ghent Altarpiece focused on two topics – questions of its theological program and issues of the panels’ stylistic coherence. While these became sites of protracted controversy, the Adam and Eve figures escaped entanglement in the scholarly disputes. First, there could be no question about their attribution: “caressed by light and shadow” in Dhanens’ words, they announced the unalloyed presence of Jan’s skilled hand.[3] Furthermore, since the First Couple played a central role in Christian redemption, their place in the program of the Altarpiece seemed unambiguous. Thus, the Adam and Eve panels were less closely examined than those on which one or more artists appeared to have worked, and they were accepted without scrutiny in analyses of the sacred story that scholars identified both in the lower register and on the outer wings.

Fig. 2. Victor Lagye, Adam and Eve in Animal Skins, 1865; Nave of St. Bavo’s Cathedral, Ghent.

By the twentieth century, moreover, the representation of explicit nudity in art, or nakedness to split a semantic hair, had ceased to be remarkable. But the rendering of human flesh was seldom scrutinized on its own terms. Kenneth Clark’s popular book on the treatment of unclothed bodies evaluated works in terms of classical norms. Jan’s rendering of Adam’s anatomy did not adhere to the ideal that Clark sought to trace in his text and was not discussed. Eve’s more stereotypical depiction, with its “bulb-like body,” better accommodated itself to the author’s ideas: “Eve in the Ghent Altarpiece is proof of how minutely ‘realistic’ a great artist may be in the rendering of details and yet subordinate the whole to an ideal form.”[4] Realism itself was studied less as an ongoing occurrence in European art than as a particular phenomenon of the nineteenth century. Jan’s exactitude, “steeped in a context of belief in the reality of something other and beyond that of the mere external, tangible facts,” was contrasted with the more recent moment when “contemporary ideology came to equate belief in the facts with the total content of belief itself.”[5] The scrupulous rendering of anatomy that Jan employed in depicting the First Couple lost out to the claims of over-arching ideals and ideas. Defined by the ideological setting in which it occurred, rather than by appreciation for its results, Jan’s work was set apart (and aside) by preconceived assumptions regarding what characterized the painter’s perceptions, even though his painting, in so many ways, closely resembled the achievements of more recent art.

Fig. 3. Ghent Altarpiece, wings closed.

Fig. 4. Singing Angels; detail of the left inside wing, upper register, Ghent Altarpiece.

From the outset, viewers of Jan’s paintings focused on his exceptional skill in examining optical effects and in feigning them, a talent that is amply displayed on the Ghent Altarpiece (Figures 3 and 4).[6] In the scene of the Annunciation that is depicted on the outer wings, shadows on the floor of the chamber within which the event occurs appear to be cast by the frames that surround the panels; on the upper register of the interior, the reflection of a lancet window that is part of the chapel architecture glitters on the surface of the jeweled brooch worn by the foremost singing angel that Jan painted on the left wing. Otto Pächt, in a stunning appreciation of Jan’s work, attributed this quality to Jan’s “stilled gaze” that enumerates and does not alter as it studies the natural world, even when it creates unusual effects.[7]

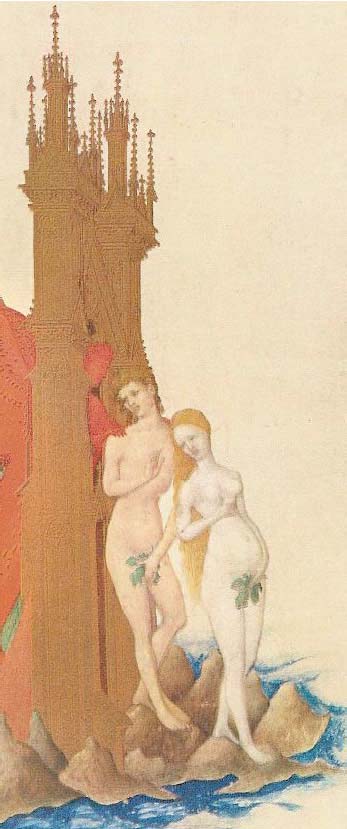

Undoubtedly the most astonishing effect of all is the one Jan assigned to Adam. His flesh, instead of being shown as uniformly darker than Eve’s, as it had been portrayed in the Garden of Eden miniature in the Très Riches Heures less than two decades earlier (Figure 5), is depicted as being dramatically dichotomous.[8] Adam holds reddened hands in front of a pale torso creating a stark contrast between what the spectator readily identifies as the representation of exposed and protected flesh.

Fig. 5. Adam and Eve expelled from Eden; detail of the Garden of Eden miniature, Très Riches Heures, f. 25v.

Scholars have assumed that the differentiation in Adam’s skin coloration resulted from Jan’s use of a model whose hands had been darkened by sunlight in the course of ordinary outdoor activity. Erwin Panofsky tersely commented on the use of a live model without pursuing the implications of his observation.[9] Pächt elaborated on Jan’s achievement, arguing that it “…would have been inconceivable without the most intensive study of the living model,” and he praised the artist for his “passive descrying” — in which he chose to add nothing to what he “optically perceived.” Pächt viewed this quality as the revolutionary achievement of Jan’s art, even as he registered a degree of discomfort with such a treatment of Adam’s body in direct juxtaposition with conspicuously overdressed members of the Celestial Court.[10]

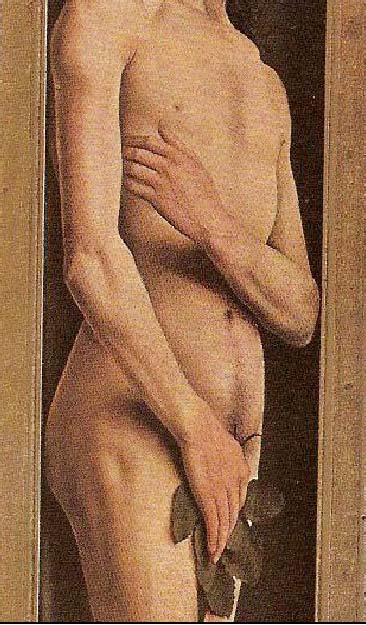

The Viennese scholar’s unwavering assertion of Jan’s “passive eye” is inconsistent with the painter’s unprecedented inventiveness and with Pächt’s own insightful description of Jan’s accomplishments; it is, moreover, intellectually naïve to think any longer of either an artist or an eye working in the way he suggested. While reproductions of the Adam figure frequently diminish the color in what is basically a monochromatic panel, the tonally darker appendages that Adam holds in front of his torso persist, at the least, as uncomfortably anachronistic details (Figure 6).

Fig. 6. Adam’s torso; detail of Figure 1.

In contrast to unexamined acceptance of naturalism as the hallmark of, and explanation for, Jan’s style, I have long been struck by the singularity of the effects it achieves, as in the instance of Adam’s hands.[11] For that reason, I pursued Jan’s dazzling and discomforting simulation of the First Couple’s anatomy as enactment of the thesis that is central to Formalist theory, namely, that the task of artistic language, poetic or visual, is to render ordinary elements extraordinary in order to make us see them in a new way.[12] In what follows, I inquire into Adam’s epidermal pigmentation by examining the technical means through which it was achieved and then consider the unprecedented significance that Jan’s rendering of the First Couple’s anatomy effectuated.

This inquiry is part of a larger project that develops other issues, ultimately suggesting that Jan’s vaunted technique of representation should be understood as something more than a supremely competent transcription of reality and likened instead to a form of experimental science.[13] His meticulous renderings combined scrupulous visual examination of his physical surroundings with rigorous attention to the material components of his craft. Together these activities, integral to his art, enabled systematic inquiry into the invisible, even mysterious, workings of the natural world. While impetus for my approach has been Formalism’s (often overlooked) edict to confront the artist’s invention as it appears to the viewer’s consciousness directly, and to pursue it in all its materiality, that does not mean that I disregard other approaches; rather, I lament the neglect of Formalism’s fundamental precepts within other schools of thought and modes of inquiry. While the point of departure in the essay that follows is an overview of historical issues, the recurrent thread throughout is concern about technique and the context of Jan’s painterly practice.[14]

In 1432, Jan van Eyck’s painterly skills were put on public display when a massive, multi-paneled altarpiece, on which he had worked with an older brother, was installed in a newly endowed chapel at the church of St. John Baptist in Ghent, now St. Bavo’s Cathedral. An extensive inscription, highly exceptional for the time, runs across the bottom frame of the exterior wings, beneath large scale kneeling depictions of the work’s donors, Jodocus Vijd and Elisabeth Borluut. This painted text praises the artists and situates the work as the earliest dated monumental piece in the Netherlandish canon.[15]

There has never been any doubt about Jan’s responsibility for the most novel painted aspects of the work, even though Panofsky attributed a pivotal role in the original conceptualization of the polyptych to his older brother Hubert.[16] Recently, researchers have acknowledged the participation of multiple hands throughout the panels, indicating the presence of apprentices working under the supervision of a master painter.[17] Nonetheless, Jan’s undisputed contributions remain readily identifiable in luminous passages of chromatic transparency and the simulation of textures; these display exceptional proficiency in the handling of oil glazes, an accomplishment for which he became celebrated within his own time.[18]

But Jan’s deserved eminence as a foundational figure for fifteenth-century painters does not reside only in his technical accomplishments: his fascination with natural phenomena precedes his rendering of them. As the Ghent Altarpiece explicitly attests, Jan’s fascination with reflections and shadows, the play of water and the formation of clouds, the diversity of botanical species and the nature of mineral and geological elements, constitutes a handbook on the structure of natural objects.[19] This cosmic corpus is analogous to the catalogue of fifteenth-century Christian iconography that is amassed by the Altarpiece’s assemblage of Biblical and historical figures.[20] In fact, this should not surprise us, since artist’s shops had, for a long time, been places in which technical knowledge regarding the proper rendering of forms and themes, as well as information concerning the grinding of colors and the composition of liquid media, circulated.[21] To judge by the few treatises that have come down to us, in particular that of Cennino Cennini, most of this information was transmitted directly, through apprenticeship; only occasionally were “trade secrets” written down for posterity.[22]

The life-size and life-like figures of Adam and Eve that frame the upper wings on the inside of the Ghent Altarpiece indisputably focus attention on Jan’s study of the natural world. They alone among the figures on the top register emerge from the shadowyrecess of stone niches that recall the masonry of the chapel for which the polyptych was commissioned. Jan distinguished the space in which they are positioned from that of the heavenly choruses at their sides as though to emphasize the first couple as human ancestors instead of historical antecedents.[23]

References to contradictory moments of their familiar story further disengage them from the familiar sequence of events that is narrated in Scripture, making them seem more like independent actors than mere agents of an oft cited tale. The small fruit that Eve holds between the fingers of her elevated right hand indicates the imminence of the Temptation; at the same time, the fig leaves with which she and Adam conceal their genitalia declare that they have already eaten of it. This configuration of familiar elements challenges features that we know from the story of the first couple as told in Genesis. There Adam and Eve’s naked bodies (Gen. 2:25) receive discreet coverage only after they have eaten the forbidden fruit. Knowledge, in the form of self-awareness gained through misbehavior, causes them to cover their lower torsos with leafy aprons (Gen. 3:7); the leaves serve as signs of their shame.

Jan’s has depicted them in this way in a conflation of sequential events. Through explicit modulations of muscle and flesh tone, he celebrates Adam and Eve’s nakedness in the moments before God clothes them with garments. Passages of precisely rendered body hair allude to the absent animal skins that provide them with cover just before their Expulsion from Eden, according to the text.[24] Early viewers were so taken with the frank representation of the first couple that they employed their names when discussing the whole polyptych, referring to it as the Adam and Eve Retable. Philip observed that this was in no way a misnomer since the figures are central to the message of the Altarpiece.[25] Bus something else was at stake as well: The Ghent painter Lucas de Heere, in an ode to the Altarpiece published in 1565, remarked on Adam’s disturbingly life-like pose, asking “who ever saw a body painted to resemble real flesh so closely?”[26]

Indeed, Adam’s anatomy is remarkably delineated. It displays dimples, bony bulges, hair follicles and skin depicted with variegated coloration. Angularly positioned arms crisscross a muscular torso, casting strong horizontal shadows along the lower chest and hip that dramatically emphasize the figure’s erect posture and draw attention to its robust physiognomy. The bold arm gesture further underscores a distinction between Adam’s pale, luminous torso and the harsh redness of his hands. This audacious representation of weathered, sunburned extremities indicates labor out of doors, the punishment God meted out to Adam for his disobedience immediately before the Expulsion. It has suggested to several scholars, Pächt and Panofsky foremost among them as noted above, the artist’s faithful transcription of reality in the use of a live model.[27]

Pächt and Panofsky each recognized that this coloration depicted heightened pigmentation following exposure to the elements, and both marveled at such a demonstration of observational fidelity on the artist’s part. Pächt went further than did Panofsky in celebrating Jan’s accomplishment, stressing that such a depiction “… would have been inconceivable without the most intensive study of the living model.” He noted that the figure of Adam “provides one conclusive proof that it is painted from life: the flesh tone of the head and hands is markedly darker than that of the rest of the body. Jan’s Adam is the portrait of a man who has laid aside his clothes and stands before the painter in the pose of our earliest ancestor, and in his state of paradisal nudity. Head and hands, the only parts of the body exposed to the light in the normal life of western man, are tanned by comparison with the paler tone of the rest.”[28]

Pächt, in his discussion, emphasized that “… instead of the nudity of Paradise, Jan gives us the minutely observed nudity of a model who is playing the part of Adam.” Blindsighted by the issue of causality – the living model Jan employed, Pächt overlooked the implications of the unprecedented effects thereby achieved. He was unable to explore the way in which the sunburnt hands recast the story of the First Man because, in this instance, his understanding of Jan’s style preceded the facts of Jan’s art. His approach excluded the notion of Jan editing what he saw. Absent that paradigm, Jan’s artistic decisions can be read as choices, and their results re-evaluated.

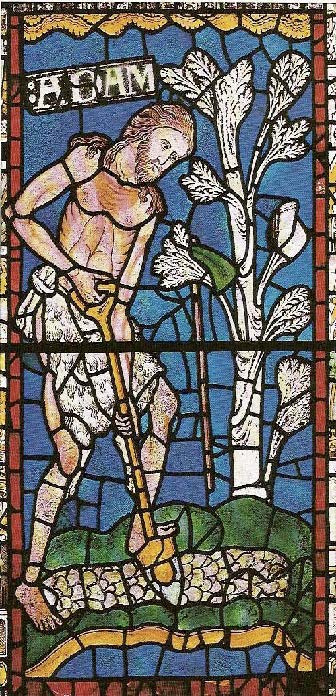

The richly pigmented hands that Jan gives to Adam contribute to a visual retelling of the Genesis story that radically revises understanding of the First Man’s status in the aftermath of the Temptation. Bold signs of sunburn and chafing draw attention to the hands as the bodily agents of manual labor. They replace the familiar spade with which Adam is elsewhere represented as a sign of his post-Edenic activity (Figure 7), confirming him thereby as a tiller of the soil.[29] The absence of garments draws attention to his bodily raiment — the shameless adornment of his own skin, and suggest that he is seen here as more than first farmer.

Fig. 7. Adam digging; stained glass originally in the north choir clerestory, Canterbury Cathedral, ca. 1180.

On the Ghent Altarpiece, anthropomorphic tools identify Adam as a laborer without limiting him to the tilling of soil; the absence of animal skins similarly distances him from his post-Edenic activity. Nudity additionally confers less time-bound stature, suggesting, moreover, that he is depicted as one who has been saved. Through these deviant details, Adam is elevated to the role of first worker; he is depicted as the originator of activities that began with his tilling of the soil. Cennnino Cennini had similarly situated Adam in his Craftsman’s Handbook, noting that the Expulsion did not eradicate God’s gift of knowledge to humankind, but rather provoked Adam’s awareness of the need to work for his living. In this way, Cennini continued, God’s wisdom was passed down through the generations in the form of a series of labors.[30]

This notion of the chain of work stretching back to the First Couple had already found visual expression in Florentine imagery several decades earlier. The mid-fourteenth- century reliefs of the Creation of Adam and Eve on the Campanile of the Duomo are juxtaposed with scenes of them at work, followed by images of the labors of their distant offspring. Three sons of Lamech figure in the Florentine imagery: Jabal, a herdsman; Jubal, the father of music; and Tubalcain, the first smithy. The Campanile reliefs, which omit scenes of the Temptation, Fall, and Condemnation, produce a novel message in which labor does not appear as punishment for sinful behavior but is presented instead as the affirming continuation of God’s purposeful actions in his creation of the First Couple.[31]

Cennino, in the introduction to his handbook, identified the craft of painting as part of this process. He defined it as an occupation requiring imagination, coupled with skill of hand, “in order to discover things not seen, hiding themselves under the shadow of natural objects, and to fix them with the hand, presenting to plain sight what does not actually exist.” Cennino identified the sources of his own knowledge in apprenticeship: twelve years of training under Agnolo di Taddeo, who was taught by his father Taddeo, who himself worked for twenty-four years with Giotto, who “brought the profession of painting up to date.”

Jan’s representation of Adam at once embodies God’s message and concretizes Cennini’s words. The Lord’s charge to Adam the moment before the Expulsion inaugurated an occupational lineage that was understood by Christians to continue, for all time, through Adam’s descendants. Jan’s depiction of Adam on the Ghent Altarpiece, with its emphasis on muscular forearms and reddened hands, proclaims the body’s capacity to engage in manual labor, a notion to which Adam’s lean but agile torso additionally attests. The artist’s positioning of the arms against the paler abdominal flesh maximizes the contrast between flesh tones, drawing attention to the bodily agents of physical work: hands are the point of origin for all human endeavors. By rendering the exposure and exertion of Adam’s hands with such deliberate detail, and then depicting them without any extraneous tool, Jan converts the mundane into the marvelous. He creates an unprecedented image of the inalienable implements of labor and, with it, makes a dramatic claim for the elevated ancestry of all work, including his own. As Cennini contemporaneously observed, the craft of painting is one of the many labors that descend from Adam’s tilling of the fields.

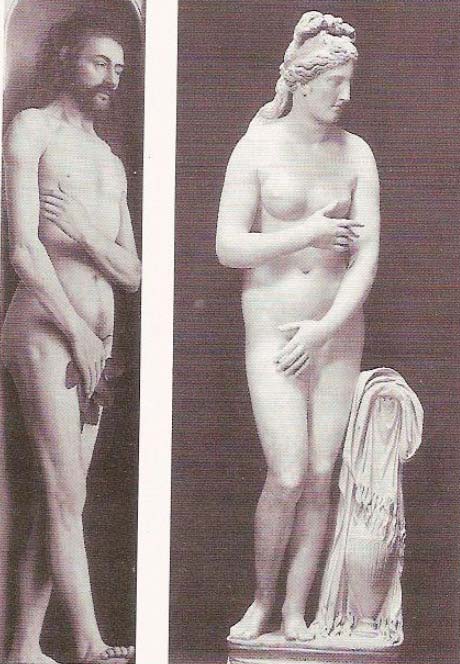

Jan invokes the imposing lineage of his art in another purely visual way, by referencing the gesture of a famous ancient statue within his own painted sculpture, and then reworking it so as to reinforce the brilliance of his own novel conception. As Pächt noted, the positioning of Adam’s arms mimics the familiar pose of the Venus pudica (Figure 8).[32] But Jan has not benignly appropriated this paradigmatic gesture of female modesty, which Masaccio, just a few short years before, had used for his own Eve in the Brancacci Chapel, a painting Jan may well have seen.[33] Jan has reversed the positions of the arms, bringing the hands closer to the picture plane. In this arrangement, their heightened pigmentation becomes more immediate for the viewer. Moreover, the painter has transposed the gesture from a female to a male figure, thereby stealing the insignia of shame and relieving it of its negativity: what, after all, does Adam’s left arm have to hide?

Fig. 8. Adam from the Ghent Altarpiece and the Capitoline Venus pudica; Figures 94 and 95 in Pächt, Van Eyck, p.193.

The inverted gesture emphasizes that the first man’s upright, dignified stance is at variance with more familiar post-banishment images in a fundamental way. Whereas clothed flesh, whether with animal skins or leaves, signifies Adam’s humiliation after his fall from grace, Jan’s figure lacks reference to any sense of guilt as traditionally conveyed either through garb or gesture. In place of the hand and arm movements that accompany Adam in Masaccio’s nearly contemporary figure in Florence as an expression of remorse, on the panel in Ghent, as we have seen, pigmentation draws attention to the proud agents of physical labor.[34] Jan presents his viewers with an unprecedented depiction of Adam as an unashamed, ennobled worker.[35]

Jan’s singular depiction of heightened pigmentation on Adam’s hands renders the effects of the sun’s rays on organic matter, an issue that engaged the attention of earlier painters in their preparation of certain materials. Cennini’s handbook testifies to this awareness in a recipe for readying oil for painting. The author instructs that linseed oil be placed in a bronze or copper basin and kept “in the sun when August comes” so that it will be reduced in quantity, perhaps through the formation of a skin on its surface. This treatment, he says, makes it “most perfect for painting,” although the absence of any explanation as to how the oil has been altered continues to frustrate modern readers of his manual.[36] On the Ghent Altarpiece panel, Jan demonstrates his awareness of the transformative powers of sunlight’s invisible energy along with his ability to render its effects. Through the foregrounding of Adam’s starkly pigmented hands, the essential tools of the painter’s craft, the artist simultaneously flaunts his own exceptional observational talent and his remarkable technical skill.

What then about Eve? Following the paradigm that has emerged here for Adam, it is difficult for me to accept claims that her representation is inscribed in the well-known negative narrative about women’s bodies and their seductive nature that stretches back to Augustine. Margaret Miles has suggested that Jan’s depiction of Eve “displays the sensuous curves that initiated the fall of the human race,” inscribing her thereby into the Christian context of guilt and shame. To be sure, Eve’s broad-hipped torso emphasizes the potentiality of her body for pregnancy; the long left arm that falls diagonally across her abdomen emphasizes this feature, a characteristic of late medieval “idealized feminine beauty” as Miles has put it.[37]

At the same time, the arm points to a vertical line of darkened pigmentation that ascends toward her navel; it has gone either unnoticed or unremarked upon in scholarly study (Figure 10). This shadowy striation sets off the highlighted surface of Eve’s swollen belly and urgently marks her with one of the unmistakable physiological signs of advancing pregnancy. Like her partner, she also bears a bodily sign of God’s injunction; she too is branded with the mark of her destiny.[38]

In Gen.3:16, God mandates that Eve will suffer the anguish of pain in childbirth, a situation to which Jan’s near life-sized figure alludes with exceptional bluntness.[39] The dark line that vertically bisects Eve’s belly corresponds anatomically to the juncture between abdominal muscle plates that is known as the linea alba. As these plates spread apart during pregnancy to accommodate the expanding uterus, the line darkens, a phenomenon usually observed around the fourth month of pregnancy. The appearance of the line on the bellies of darkly complexioned Caucasian women has been most often noted by midwives. It is commented upon in gynecological treatises from the late eighteenth century on as signaling the “quickening” of the fetus; because of its pigmentation, it is referred to at this stage as the linea nigra. Description of this phenomenon is not known to me in any medical practitioner’s treatise of Jan’s time, but an image of a nude pregnant woman, shown squatting in a medical miniature of about 1400, suggests an emerging curiosity about the gravid female body at a time when first-hand descriptions remain, for the most part, infrequent and imprecise.[40] On the large panel in Ghent, visual representation trumps textual silence; Jan’s painted depiction inscribes knowledge of this phenomenon of pregnancy into the visual record.

For Pächt, a representation like the one of Adam, necessitated confrontation with a living model, a suggestion that would be difficult to deny. Although he did not remark on the striation on Eve’s abdomen, I doubt that Pächt would have claimed study from life for her as well; it would have been unthinkable, and unseemly, to do so. Yet Jan’s rendering of the linea nigra testifies to his direct awareness of localized changes in the pigmentation of a woman’s skin during pregnancy, something he could have observed during his wife’s several gestations. On the Ghent panel, he audaciously documents this intimate experience of a subtle and seemingly miraculous alteration in abdominal coloration in his depiction of Eve, framing the pigmented line with exploration of the translucent properties of stretched skin. Eve does not seem to be at all ashamed by the revelation of her “condition;” as though to remind the viewer of that, Jan explicitly eschewed use of the familiar antique pose of modesty in the placement of her gestures, positioning her arm instead so that it frames her torso.

Eve’s belly, like Adam’s hands, served as the instrument through which God’s words of admonition were to be realized in human history according to Scripture. The exceptional markings with which Jan van Eyck defined these body parts on the Ghent panels result from his close observation of nature, physiological change on the one hand, the power of the sun’s rays on the other; one activity is internal to the body, the other, external. Jan’s allies the organic materials of his craft with description of these natural processes, employing his pigments to depict the activity of otherwise unseen energy, presenting “to plain sight what does not actually exist,” the work Cennino had said artists should do.

This was one of the qualities that Jan’s contemporaries took note of in their praise of his art.[41] His success in portraying the activity of the sun’s rays as they produce reflections, shadows, translucencies, and transformations in tonality indicates intense study, on Jan’s part, of the circumstances surrounding such phenomenological occurrences, not merely interest in their dazzling results. Though Jan may not have been the “inventor of oil painting” in the way that earlier generations claimed and some texts still assert, his signature use of oils and glazes to render his observations made significant contributions to subsequent developments in painting. The written comments of artists such as Dürer, who was taken to see the Altarpiece during a visit to Ghent in the 1520s confirm that Jan’s panels passed on knowledge of his achievements; they contributed to the construction of a legend regarding his accomplishments in the depiction of luminosity in paint.[42]

Although I have not read the polyptych as a theological, political, or social program, in which Adam and Eve are viewed through the lens of either exegetical or contemporary commentary, I have come to regard the panels nonetheless as a kind of pictorial “text,” in which Jan, like his compatriot Cennini, addresses an array of technical and visual challenges, and resolves them with ingenious solutions. Jan’s Adam and Eve, I argue here, profit from being studied in terms of their idiosyncratic artistic achievements and scrutinized in terms of their painter’s artistic practices. As that is done, attention focuses on aspects of their representation that have previously been insufficiently addressed, inviting us to reexamine and revise received certainties about their behavior that we have been told, and which we may be telling others. As a result, we gain new appreciation of their painter’s achievement and enhanced understanding of the figures’ meaning.

Linda Seidel is the Hanna Holborn Gray Professor Emerita at the University of Chicago where she taught art history for nearly thirty years. Throughout her career, her research into understudied aspects of well known objects was stimulated and nourished by students’ questions and concerns. Her books include Songs of Glory, Legends in Limestone, and Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait: Stories of an Icon.

References

| ↑1 | For documentation regarding the Altarpiece, with discussion, see the several publications of Elisabeth Dhanens, Het retabel van het Lam Gods in de Sint-Baafskathedral te Gent..Inventaris van het Kunstpatrimonium van Oostvlaanderen (Ghent: KunstPatrimonium, 1965); Van Eyck: The Ghent Altarpiece. Art in Context (New York: The Viking Press, [1973]), 127-137; Hubert and Jan van Eyck (New York: Tabard Press, 1980), 74-121. For an account of its fate during W.W. II, see Lynn H. Nicholas, Rape of Europa; the Fate of Europe’s Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War (New York: Knopf, 1994), 143-5 and 347. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Peter Schmidt identifies Victor Lagye as the mid-nineteenth-century painter of the clothed copies (1865). See The Adoration of the Lamb (Leuven: Davidsfonds [1995]), 13. |

| ↑3 | Dhanens, Hubert and Jan, 111. |

| ↑4 | Kenneth Clark, The Nude: a Study in Ideal Form. Bollingen Series no.35. A.W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts 2 (New York: Pantheon Books, 1956), 318-319. Although John Berger’s attention to the treatment of the female body in painting focused on the issue of the gaze, like Clark’s work, it opted for “image-bites” in place of close analysis of individual works (Ways of Seeing [London: BBC and Penguin Books, 1972], 36-64). |

| ↑5 | Linda Nochlin, Realism. Style and Civilization (Harmondsworth and New York: Penguin Books, 1971), 20 and 45: “Van Eyck … and Caravaggio…, no matter how scrupulous they might have been in reproducing the testimony of visual experience, were looking through eyes, feeling and thinking with hearts and brains, and painting with brushes, stepped in a context of belief in the reality of something other and beyond that of the mere external, tangible facts they beheld before them … it was not until the nineteenth century that contemporary ideology came to equate belief in the facts with the total content of belief itself: it is in this that the crucial difference lies between nineteenth-century Realism and all its predecessors. |

| ↑6 | For Bartolomeo Fazio’s mid-fifteenth-century appreciation of Jan’s work, see Michael Baxandall, “Bartholomaeus Facius on Painting. A Fifteenth-Century Manuscript of the De Viris Illustribus,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 27 (1964): 90-107 (esp. 102-03), and Giotto and the Orators: Humanist Observers of Painting in Italy and the Discovery of Pictorial Composition (Oxford: the Clarendon Press, 1971), 97-101. https://doi.org/10.2307/750513 |

| ↑7 | Otto Pächt, Van Eyck and the Founders of Early Netherlandish Painting, foreward by Artur Rosenauer, trans. David Britt, ed. Maria Schmidt-Dengler (London: Harvey Miller, 1994), 24. |

| ↑8 | For the well-known manuscript, with commentary on the Eden miniature on f.25v, see The Très Riches Heures of Jean, Duke of Berry, intro. Jean Longnon and Raymond Cazelles (New York: George Braziller, 1969), no. 20. |

| ↑9 | Erwin Panofsky, Early Netherlandish Painting; Its Origins and Character, 2 vols. (Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, 1953), I:223: “Jan van Eyck’s consummate naturalism is evident from the difference, indicating the use of a living model, that exists between the pale complexion of Adam’s body and the tan of his hands.” Hereafter ENP. |

| ↑10 | Pächt, Van Eyck, 163-4: “With supreme and, one might almost say, brazen disregard for the demands of his iconographic programme, as well as for those of illustrative decorum, Jan van Eyck records what his physical eyes see, without alteration or embellishment.” Max J. Friedländer had earlier noted that the Adam and Eve figures were “painted with such utter realism that they seem almost incongruous with the rest of the altarpiece.” Early Netherlandish Painting, pref. Erwin Panofsky, comments and notes Nicole Veronee-Verhaegen, trans Heinz Norden, 14 vols. (Brussels and Leiden, 1967 – 1976) I: 25 |

| ↑11 | Seidel, “The Value of Verisimilitude in the Art of Jan van Eyck,” in Yale French Studies, spec. ed., Contexts: Style and Values in Medieval Art and Literature, eds. Daniel Poirion and Nancy Freeman Regalado (1991): 24-43. https://doi.org/10.2307/2929092 |

| ↑12 | For my overview of this venerable approach, see “Formalism,” in A Companion to Medieval Art: Romanesque and Gothic in Northern Europe, ed. Conrad Rudolph (Malden MA.: Blackwell Publishing, 2006): 106-27. |

| ↑13 | Certain issues introduced here are treated in greater detail and from a different perspective in Linda Seidel, “Jan van Eyck and The Ghent Altarpiece: Visual Representation as Instructional Text,” Making Knowledge in Early Modern Europe: Practices, Objects, and Texts, 1400-1800, ed.. Pamela H. Smith and Benjamin Schmidt, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007): [scheduled Oct]. |

| ↑14 | For a recent discussion of other approaches, see Early Netherlandish Painting at the Crossroads: A Critical Look at Current Methodologies, ed. Maryan W. Ainsworth. Metropolitan Museum of Art Symposia, 3rd, 1998 (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2001). My own work has been immeasurably enabled by advances in technical studies of the sorts described therein. |

| ↑15 | The literature on the Ghent Altarpiece is extensive. In addition to the works by Dhanens, Panofsky and Pächt, already cited, works I have referred to time and again over the course of the years include Lotte Brand Philip, The Ghent Altarpiece and the Art of Jan van Eyck (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1971); Paul Coremans et al, L’Agneau mystique en laboratoire. Examen et traitement, Les Primitifs Flamands III, Contributions à l’étude des primitifs flamands 2 (Antwerp: de Sikkel, 1953); and J.R.J. van Asperen de Boer, “A Scientific Re-examination of the Ghent Altarpiece,” Oud-Holland 93 (1979): 141-214. https://doi.org/10.1163/187501779X00014 |

| ↑16 | Panofsky, Early Netherlandish Painting, 205-230. For a more recent consideration of the Hubert and Jan controversy, with different attributions of particular panels including those of the First Couple, see Claus Grimm, Meister oder Schuler? Berühmte Werke auf dem Prufstand (Stuttgart: Belser Verlag, 2002), 100-01. |

| ↑17 | Till-Holger Borchert, “Introduction. Jan van Eyck’s Workshop,” in Till-Holger Boerchert et al., The Age of van Eyck: The Mediterranean World and Early Netherlandish Painting. 1430-1530 (London: Thames and Hudson, 2002), 8-25 (esp.14-15). |

| ↑18 | See Fazio’s remarks, as in n. 5. |

| ↑19 | The precisely rendered trees and flora in the lower panels, several of which Jan could only have seen during travels outside of the Lowlands, were enumerated by L. Hauman, in L’Agneau mystique au laboratoire, 123-24. |

| ↑20 | See Pächt, Van Eyck, 124-70; also Dana Goodgal, “The Iconography of the Ghent Altarpiece” (Ph.D. diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1981), with a helpful, if now dated, bibliography topically arranged (363-387). |

| ↑21 | On shop practices, see Lorne Campbell, “L’Organisation de l’atelier,” in Les Primitifs flamands et leur temps (Louvain- le-Neuve: La Renaissance du Livre, 1994), 88-99 and Gervase Rosser, “Crafts, Guilds and the Negotiation of Work in the Medieval Town,” Past and Present 154 (1997):3-31, esp. 30-31. https://doi.org/10.1093/past/154.1.3 |

| ↑22 | Cennino d’Andrea Cennini, The Craftsman’s Handbook: Il Libro dell’Arte, trans. Daniel V. Thompson, Jr. (New York: Dover Publications, 1960); Cennini is thought to have written his work towards 1400 in Padua. See as well, the earlier, twelfth-century work by Theophilus Presbyter, On Diverse Arts. The Treatise of Theophlus, trans. and intro. John G. Hawthorne and Cyril Stanley Smith (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1963). |

| ↑23 | Lotte Brand Philip drew attention to the ways in which the independently hinged panels with the First Couple could have been repositioned in the original stone super-structure, an issue that should not be overlooked in any assessment of their distinct size and mode of depiction. She stressed that the figures “belong to human reality. As the painted continuation of the carved frame … they form part of the world of material shapes in the physical environment of the spectator.” in The Ghent Altarpiece and the Art of Jan van Eyck (Princeton N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1971), 17-18. Warm thanks to Andrée M. Hayum for continuing conversations over the years regarding Philip’s contributions to our understanding of the Ghent Altarpiece. |

| ↑24 | After God’s admonition of the couple, He dresses them in garments that He fashions for them; this event directly precedes the couple’s banishment from the Garden and Adam’s assumption of his responsibilities as a tiller of the soil (Gen. 3:21). |

| ↑25 | Philip, The Ghent Altarpiece, 48 n. 89 and 72 n. 144. |

| ↑26 | Karel van Mander, The Lives of the Illustrious Netherlandish and German Painters, from the first edition of the Schilder-boeck, 1603-04, intro and ed. Hessel Miedema, 2 vols. (Doornspijk: Davaco, 1994-5), I:62. See also Walter J. Melion, Shaping the Netherlandish Canon: Karel van Mander’s Schilder-boeck (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991), 85 and 137-38. |

| ↑27 | Dhanens observed this too; see Van Eyck: The Ghent Altarpiece, 122-123: “Adam and Eve were clearly drawn from life, and by Jan, the uncompromising portrait painter, whose concern is to represent the individual as he appears at a given time and place.” |

| ↑28 | Panofsky, Early Netherlandish Painting, 221-223, and Pächt, Van Eyck, 162-164 |

| ↑29 | For the stained glass figure of Adam, see Madeline Caviness, The Early Stained Glass of Canterbury, circa 1175-1220 (Princeton N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1977), 113 and, with more wide reaching commentary, Michael Camille, “’When Adam Delved’: Laboring on the Land in English Medieval Art,” in Del Sweeney, ed., Agriculture in the Middle Ages; Technology, Practice and Representation (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1995), 247-76, esp 249- 50 and 272-3. |

| ↑30 | Cennini, The Craftsman’s Handbook, 1. |

| ↑31 | Diana Norman, “The art of knowledge: two artistic schemes in Florence,” in Siena, Florence and Padua. Art, Society and Religion 1280-1400, 2 vols., ed. Diana Norman (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1995), II: 217-241, esp. 222, where Norman remarks on the “very positive” message of the reliefs, finding in them the prospect that “human beings can contribute to their redemption” through the acquisition of “both practical skills and theoretical knowledge.” I do not intend to suggest that the Florentine work was the source for Jan’s conception but introduce it instead as an additional example of an alternative way of thinking about Adam’s activities pursuant to the Expulsion. |

| ↑32 | Pächt, Van Eyck, 163, and figs. 94,95. The curious appropriation of a gesture associated with a celebrated female figure for a male form eluded Pächt’s interest. For the antique models, see Clark, The Nude, 85-87. |

| ↑33 | The likelihood that Jan traveled to Italy in 1426 or 1428 and saw specific works of art while there is persuasively explored by Penny Howell Jolly with compelling results. See “Jan van Eyck’s Italian Pilgrimage: A Miraculous Florentine Annunciation and the Ghent Altarpiece,” in Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 61 (1998): 369-94. https://doi.org/10.2307/1482990 |

| ↑34 | For discussion of the contemporary Florentine rendering of the fallen Adam and Eve, see James Clifton, “Gender and Shame in Masaccio’s Expulsion from the Garden of Eden,” Art History 22 (1999): 637-55. For extensive study of the Brancacci Chapel, see Nicholas A. Eckstein ed., The Brancacci Chapel: Form, Function and Setting. Acts of an International Conference. Florence, Villa I Tatti June 6, 2003 (Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 2007); Rona Goffen’s paper explicitly deals with the figures discussed here (“Adam and Eve in the Brancacci Chapel, or Sex and Gender in the Beginning,” 115-38). I am most grateful to Risham Majeed for bringing these studies to my attention. |

| ↑35 | Jan’s invention needs to be integrated into the study of the representation of labor in the late medieval period something for which there is not time here; Jonathan Alexander’s investigations form the threshold for such a pursuit. See “Labeur and Paresse: Ideological representations of Medieval Peasant Labor,” Art Bulletin 72 (1990): 436-52. https://doi.org/10.2307/3045750 |

| ↑36 | Cennnini, Craftsman’s Handbook, 59. |

| ↑37 | Margaret R. Miles, Carnal Knowing. Female Nakedness and Religious Meaning in the Christian West (Boston: Beacon Press, 1989), 97-99. For additional interpretations of Jan’s Eve that differ from the one I advance here, see Madeline Caviness, “Obscenity and alterity: images that shock and offend us/them, now/then?” Obscenity: Social Control and Artistic Creation in the European Middle Ages. Cultures, Beliefs and Traditions 4, ed. Jan M. Ziolkowski (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1998), 1-17 and Jacques Paviot, “Les tableaux de nus profanes de Jan van Eyck,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts, 135 (2000): 265-82. |

| ↑38 | Karen Cherewatuk of St. Olaf’s College in Northfield, Minnesota asked me about Eve’s abdominal pigmentation after a presentation I gave on that campus in 1996. The inadequacy of my ability to explain it then has haunted me over the years, ultimately pushing me to the account I have fashioned here. I have been grateful to Professor Cherewatuk ever since for her initially uncomfortable but most provocative challenge. |

| ↑39 | I was happy to notice that Elaine Pagels’ analysis of the early Church’s attitude towards the words God speaks to Eve sets Julian of Eclanum’s argument that pain is a natural part of the birth process against Augustine’s association of the Lord’s words explicitly with punishment, although I have no reason to believe that Jan was aware of that text. See Adam, Eve, and The Serpent (New York: Random House, 1988), 127-137. |

| ↑40 | For the image, see I.G. Dox, J.L. Melloni, and H.H. Sheld, Melloni’s Illustrated Dictionary of Obstetrics and Gynecology (New York: The Parthenon Publishing Group, 2000), 210. Reference to the miniature can be found in Michael J. O’Dowd and Elliot E. Philipp, The History of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (New York: The Parthenon Publishing Group, 1994), 59. Danielle Jacquart has drawn attention to early evidence of interest in particularities of patient care beginning around the start of the fifteenth century. See “Theory, Everyday Practice, and Three Fifteenth- Century Physicians,” in La science médicale occidentale entre deux renaissances [XIIe s. –XVe s.] (Aldershot; Brookfield VT: Variorum, 1997), 140-60]. |

| ↑41 | For Fazio’s remarks, see above, n.5. |

| ↑42 | For Dürer’s remarks, see The Writings of Albrecht Dürer, trans. and ed. by William Martin Conway (New York: Philosophical Library, 1958), 117. |