Madeline Caviness • Tufts University

Recommended citation: Madeline Caviness, “From the Self-Invention of the Whiteman in the Thirteenth Century to The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 1 (2008). https://doi.org/10.61302/YOTW3684.

The Christian viewer in Europe between the eleventh and fourteenth centuries was confronted with polarized models of appearance and behavior, some to be aspired to and others to be strenuously avoided.[1] So a viewing community was formed that identified with the good, and constructed an alien “Other”. The pattern is familiar to all who have studied social constructions of race, class or gender, yet I will show that the “Self” that constructed these “Others” has been naturalized with a nebulous and timeless white identity that has not been sufficiently historicized.

In this article I explore the historical contingency of white identity through two visual models, modern film and medieval painted figures. Each model has its own historical context, including conditions that are sometimes assumed to be causes, such as the racism in the United States that informed cultural production in the mid-twentieth century, or Christian attitudes to infidels during the crusades. Yet when two such historically distinct discourses of skin color are juxtaposed, the theoretical question can be shifted from a recitation of the definitions of the other, to a theoretical understanding of self-representation as a performative that maintains (the claim of) supremacy. As in my studies of gender, I postulate psychological conditions that operate as causes and effects in a cycle of fear and aggression. Thus a three-dimensional triangle in which “whiteman now” is in a closer plane that “whiteman then,” and distinct historical contexts maintain their alterity, can be pulled into a single register in its theoretical base. It is precisely that torsion which gives it force: Ironically for those who declare the present to be irrelevant to the past, it is often the present that renders the past relevant to more enquiring minds.

My chosen framework tacitly makes the claim that visual models do ideological work more powerfully than texts, not only in predominantly oral cultures (such as the European middle ages) but also in modern popular cultures in which film and advertising are seen by all. The response to visual input is fundamentally human: Without very acute senses of smell or hearing, humankind depends a great deal on sight for warnings of danger. And we quite rightly have heightened anxiety about our own kind, since we are the most destructive species on earth, and the one most likely to kill others of our own species. Thus, the onus has been placed on our visual arts to teach us how to recognize bad people from good, treacherous from trustworthy. Such stereotyped visual clues seldom correspond with actual conditions of danger, yet their clarity and simplicity may be palliative.

Fig. 1. Detail of Heaven, Saint-Foi, Conques, west portal, , ca. 1135 (photograph by author).

Fig. 2. Detail of Hell, Saint-Foi, Conques, west portal, ca. 1135 (photograph by author).

This psychological need was met in the high Middle Ages by countless visual images of saints and angels, juxtaposed with cruel torturers and devils.[2] In the Last Judgment sculpted above the two doors of the Romanesque pilgrim church of Sainte-Foi in Conques, the faces and body-language of the angels and the saved are calm and beautiful; the demons and the damned are contorted and ugly (Figures 1-2).[3] As Umberto Eco has pointed out, medieval Christian theologians from at least the twelfth century on expected that inner goodness manifest itself in a beautiful outward appearance, though of course they distinguished this from mere sensuality, and decorum was essential to beauty.[4] Augustine adopted Cicero’s notion that bodily beauty lies in symmetry or harmony of limbs and “a certain pleasing color” (quaedam coloris suavitate).[5] The evil and the ugly have a place in this system, to provide a contrast with the good and beautiful.[6] Thus on entering the early twelfth-century church of Sainte-Foi of Conques in central France, pilgrims could choose to enter on the side of heaven – through the left door which is under the right or dexter side of god in judgment (to keep on his right side as we say), and exit through the right door on the sinister side of god, as if leaving hell (Figure 3).

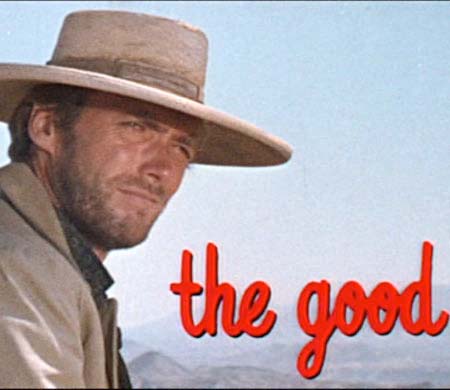

Such considerations no doubt fuelled my fascination, as a medievalist, with Sergio Leone’s 1966 production, The Good The Bad and the Ugly. An Italian Western, shot in Spain, it was originally titled Il Buono, Il Brutto, Il Cattivo (Figure 4). The genre is almost a parody of the Hollywood prototype, yet romanticizes it to the level of fairy-tale; this makes the workings of ideology more powerful.[7] I claim that this long rambling movie forms a viewing community (that is it entrains its audience) to naturalize certain facial types and body language as good or bad. As Clint Eastwood playing Joe, or “Blondie,” is introduced and labeled as the Good, and Lee Van Cleef in the role of Sentenza, or “Angel Eyes,” as the Bad, we might immediately think of the personifications of good and evil that abounded in the high middle ages (Blondie is on the left in the poster, Angel Eyes top right, Figure 4). Leone left out simplistic stereotyping, such as mostly bad Indians, and complicated the polar Good-Bad by triangulating them with the Ugly (Figure 4, lower right).

Fig. 3. Saint-Foi, Conques, west portal, ca. 1135 (photograph by author).

Fig. 4. Il Buono, Il Brutto, Il Cattivo, poster, Frayling Collection.

Fig. 5. Joe (Blondie), the Good, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, film still, 1966.

Fig. 6. Tuco and Blondie, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, film still, 1966.

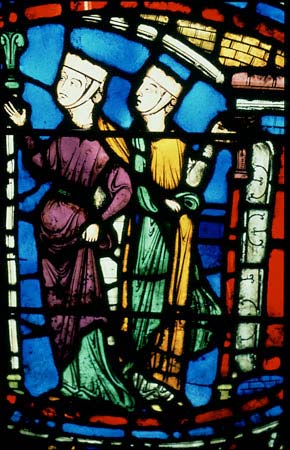

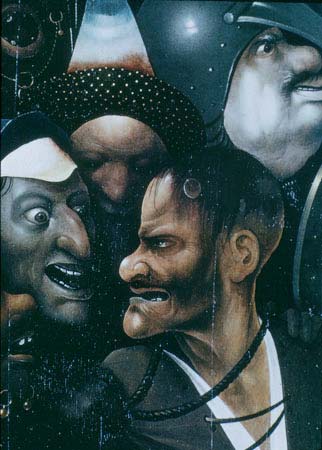

Fig. 7. Hieronymus Bosch, Christ Bearing the Cross, detail of Tormentors of Christ, ca. 1515, Ghent, Museum of Fine Arts.

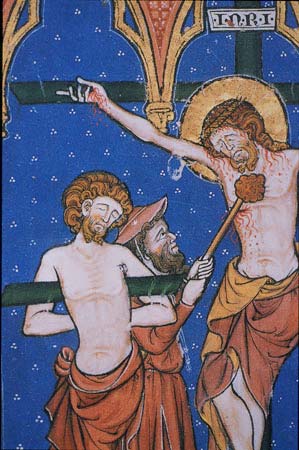

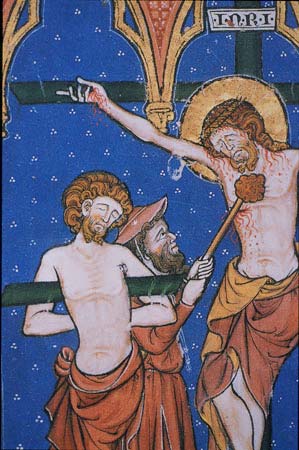

Nicknames, which are how we remember the characters, can override first appearances – “Blondie” is white, no matter how sun burned or grimy.[8] His eyes are blue, but we do not see his blond hair (Figure 5). He is a “natural leader,” inexpressive, the silent strong phallic man, with no love interest. He suffers at the hands of the ugly by the wayside, bloodied and staggering like Christ carrying the cross (Figures 6, 7). The Bad is handsome but sinister, always dressed in black. He is somewhat dark skinned, slant or narrowed eyes, with a large nose, and what the actor himself referred to as “a beady-eyed sneer” (Figure 8).[9] His severe flat-brimmed hat shades his face, so we never see his hair, a classic racial marker in modernist anthropology; he could be “Indian” (native American). He hides the death and destruction that he carries remorselessly with him under the winsome guise of the handsome; he in fact beats up the woman whose face he fingers in this frame (Figure 9).[10] In a similar way, around 1230 the sculptors of Strasbourg Cathedral hid the evil side of the male Tempter who is wooing the Foolish Virgins–behind his comely alluring figure are toads and maggots clinging to his back (Figure 10).[11] In medieval discourse it is more often women who were sensually beautiful and therefore possibly deceptive and dangerous, and their role is usually – as also in the western movies – to advance the subjectivity of the male characters. King Herod chucks Salome’s chin in the twelfth-century capital from Toulouse; her beauty made him collude with her wicked revenge on John the Baptist – and made John a sainted martyr (Figure 11). The comely prostitutes who waylay the Prodigal Son in the early thirteenth-century window of Chartres Cathedral might be mistaken for high-born ladies were it not for their tight girdles and close-fitting chemises (one of them yellow).[12] However, their invitation to sin leads ultimately to the son’s redemption; none is offered to them in the terms of the narrative parable (Figures 12, 13).[13]

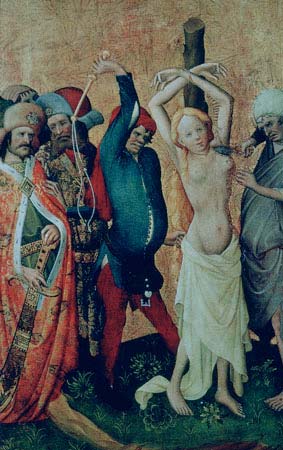

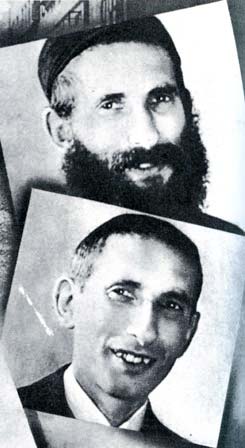

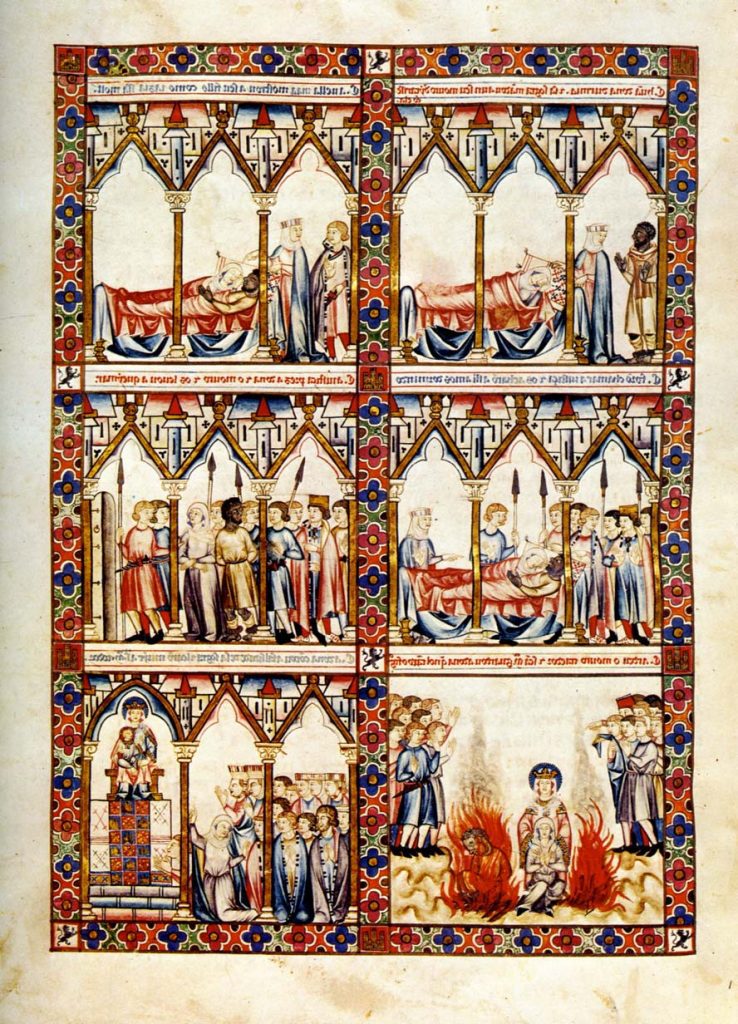

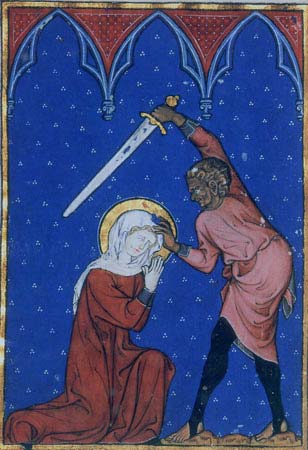

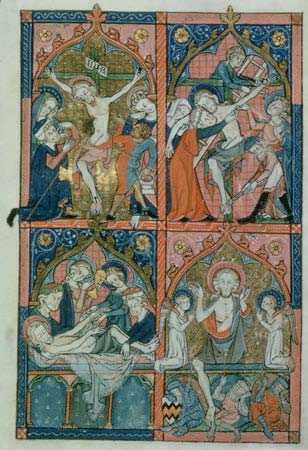

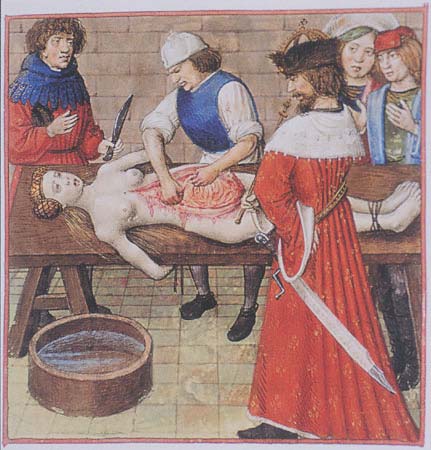

Tuco, a name or nickname of unclear derivation, is also dark-skinned, and frequently mocks Eastwood as “Blondie” (Figure 14). Eli Wallach deliberately parodied Mexicans, even though he knew some had resorted to vandalism in one movie theater over their cinematic stereotyping as “dirty, vengeful, yelling and shooting.”[14] Tuco is a buffoon, but shifty, unstable, untrustworthy, a wanted criminal with a price on his head. His squinting eyes are uncomfortably like those of the Jews photographed under bright lights for the Nazi propaganda film made by Fritz Hippler in 1939-40, Der ewige Jude (The Eternal Jew) (Figures 15, 16). As Baruch Gitlis has said of them: “their facial expressions were supposed to create the impression of criminals,” and for some facial shots Hippler used a wide-angle lens “which tended to enlarge the nose and give the smile a comic or even a somewhat sinister and leering appearance”[15] Tuco’s dark skin and exaggerated facial expressions also recall those of late medieval torturers and executioners, or Jews mocking Christ as represented by Hieronymus Bosch (Figures 17, 18).[16] Indeed, the footage before this scene, in which he leads Blondie across the desert, taunting him, resonates with the legend of the “Eternal Jew” Ahasuerus, who prevented Jesus from resting in the shade on the way to Galilee, and was condemned to wander eternally.[17] Tuco is the most extreme negative ethnic stereotyping in the film, representing a despised “Other.” A scene of the torture of Saint Agatha in a late thirteenth-century French manuscript contrasts the pure white body of the saint with the dark-skinned grimacing henchmen who are usually the ugly agents of a more majestic evil emperor: one of Tuco’s facial expressions seems to mimic them (Figures 19, 20).[18] Complete with a huge bag of gold, Tuco the Ugly is a personification of miserliness or greed, as seen on church portals (Figures 21, 22).[19] And early in the film he is condemned to hang for having raped a white woman. For a similar offense a dark-skinned Moor in Spain was said to have been burned alive, according to the legends of the Virgin illustrated in the Cantigas de Santa Maria in the second half of the thirteenth-century; the Virgin saved the woman whose mother-in-law had introduced her slave to the bedchamber (Figure 23).[20]

Fig. 8 .Sentenza (“Angel Eyes”) the Bad, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, film still, 1966.

Fig. 9. Sentenza (“Angel Eyes”), the Bad, with Bill Carson’s Woman, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, film still, 1966.

Fig. 10. Tempter and Foolish Virgin, Strasbourg Cathedral, west portal, , ca. 1230 (photograph by author).

Fig. 11. Death of Saint John the Baptist, Cathedral of Saint-Etienne, Toulouse, capital, ca. 1120-1140, Musée des Augustins, Toulouse (photograph by Rachel Dressler).

Fig. 12. Prostitutes welcoming the Prodigal Son, Prodigal Son window, Chartres Cathedral, 1205-15 (photograph by author, above left).

Fig. 13. Two prostitutes, Prodigal Son window, Chartres Cathedral, 1205-15 (photo by author).

Fig. 14. Tuco, the Ugly, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, film still, 1966.

Fig. 15. Tuco, the Ugly, grimacing at the Good, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, film still, 1966.

My concern here, however, is not whether to regard the western as a kind of medievalism, nor whether Sergio Leone drew upon medieval sources, and I note only briefly the longue durée of the negative stereotypes he used. No doubt, these enduring portrayals instill in those who identify with the Good, a degree of fear and hatred for the Bad and the Ugly. Yet with so much recent writing about the propensity for social groups to construct an oppositional Other (extending of course to women as the other sex), and of colonists to “Orientalize,” we need to defamiliarize the process.[21] I set out to do that by reexamining the Christian European construction of a “Self.”[22] As stated by Peter Linehan and Janet L. Nelson, albeit in relation to constructs of history: “Identities, medieval and modern, are constructs of selves and others at the same time.”[23] A vivid memory of my first experience teaching art history, at Wellesley College in 1969, is of an African- American student who had failed her slide identification exam. In response to a painting by Fra Angelico, she commented only that it contained “very white people.” The remark finally makes sense to me.

Fig. 16. Jew hiding his Jewish characteristics, Der ewige Jude, film still, 1939-40 (after Gitlis).

Fig. 17. Tuco and Blondie, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, film still, 1966.

Fig. 18. Hieronymus Bosch, Christ Bearing the Cross.

Fig. 19. Ethnic Torturer of Agatha, detail, Le Livre d’images of Madame Marie, ca. 1300. Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, MS. n. a. fr. 16251, fol. 97v.

Fig. 20. Tuco, the Ugly, grimacing with mouth open, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, film still, 1966.

Fig. 21. Avarice, south central France, ca. 1125-50, Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, Charles Amos Cummings Fund, 48.255 (photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2006).

Fig. 22. Tuco, the Ugly, with bag of gold, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, film still, 1966.

Fig. 23. Woman accused of adultery with a Moor, Las Cantigas de Santa Maria, ca. 1250-75, El Escorial, Real Biblioteca de San Lorenzo, Cod. T. I. 1, cantiga clxxxvi, fol. 244 (© Patrimonio Nacional).

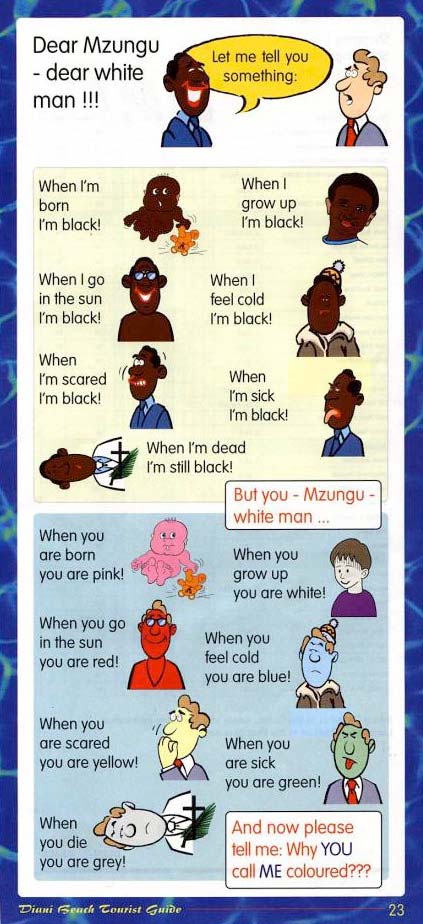

So I eventually found myself asking a completely new question: When did Europeans become so eager to represent themselves visually as, should we say pure white? I should emphasize here that I am not engaging fully in an examination of verbal discourse, because, apart from the magnitude of such a project, it is unlikely that the many genres of writing conform to the patterns that emerge here in the visual arts.[24] However, the simple term “white” has long ago been naturalized, though we know we come in all shades of pink and beige, even in the course of our lifetime – the point is wittily made in the cartoon “Dear Mzungu – dear white man!!!” on the PakTribune web site (Figure 24).[25] The idea of consistent whiteness has persisted even in the face of an attempt to deconstruct the white/black polarity that dominated some political and social systems; the imaginary field invoked by the current term “people of color” is still white. Even in French one speaks of “les blancs,” despite the term “carnation” (a shade of pink) used to describe flesh color in works of art. The identity of the self is surely as much a construct as the identity of the other. The ideal “I” or “we” provides models for performative identification – with heroes like Clint Eastwood and Christ (Figures 25, 26). Despite all the very useful work done toward the end of the last century on representations of black people in western art, this other question – about white people — has not been asked.[26]

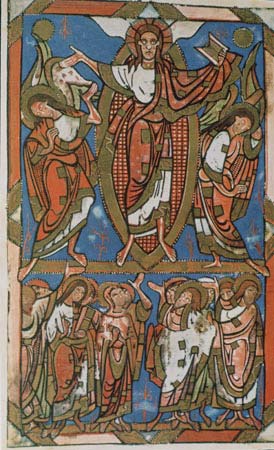

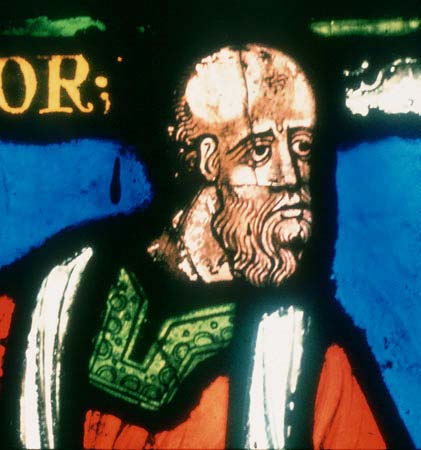

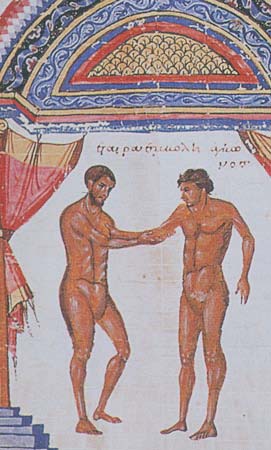

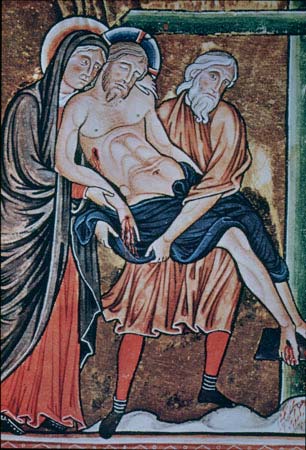

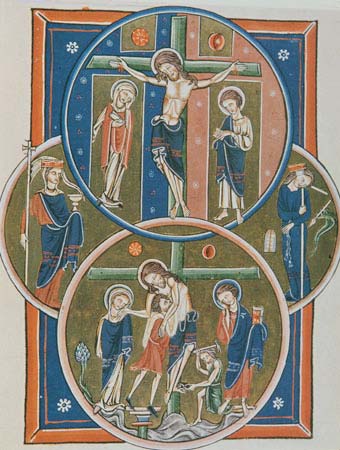

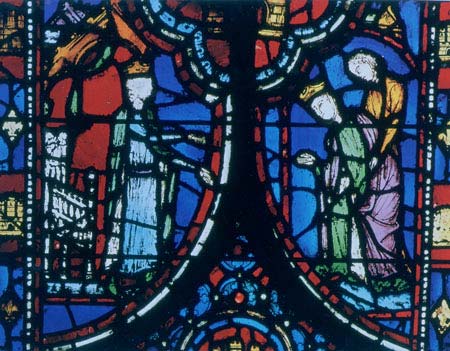

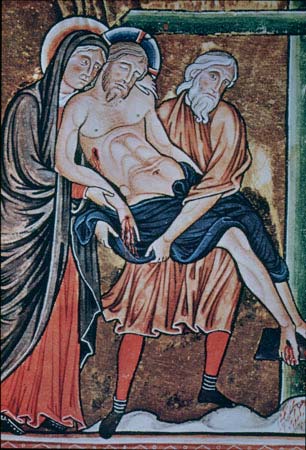

We can denaturalize such a white appearance historically by looking at visual representations through time.[27] In a tradition that stemmed from antiquity, Byzantine and early medieval painters applied heavy layers of pigment to faces and bodies, working up the relief contours to pinkish highlights. Typically, only the whites of the eyes are pure white (Figures 27, 28).[28] Early twelfth-century European works that have little to do with Byzantine style – such as the great Catalan wall paintings or a famous service book from Limoges in France — also depict rich flesh tones, dramatically contrasted with white garments (Figures 29, 30).[29] European artists adhered to these traditions through the early thirteenth century. Even in the north, they usually built a face up from a bluish or greenish modeling wash, through varied tones of brown and pink, to highlights, and much brighter whites of the eyes. These effects can be seen in English works of the late twelfth century; the Great Psalter from Canterbury, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale MS lat. 8846, and the Bible in Winchester Cathedral Library provide good examples of this chromatic range in manuscript painting (Figure 31).[30] Layered modeling is also seen in contemporary glass paintings in Canterbury Cathedral (Figure 32).[31] To achieve these effects in stained glass it was necessary to apply grey modeling washes on both sides of the glass, firing it at least twice to secure the paint.[32] The base color in this period was almost always a rosy-pink glass containing manganese, although women’s complexions were often lighter than men’s.[33] Black people were rendered in blue glass (no black was available), or in black pigment. All of these works might be said to agree with the dictum of Bartholomaeus Anglicanus, the thirteenth-century author of a treatise “On the Properties of Things,” that gradations of skin color, from deepest black, through brown, to red, pale, and white, existed between Africa and northern Europe, since he found only Slavs to be white.[34]

Fig. 24. “Dear Mzungu—dear white man!!!”

Fig. 25. Head of God in Majesty, Amiens Cathedral, central west portal, 13th c., Lithos Pictures.

Fig. 26. Joe (“Blondie”), the Good, with cannon, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, film still, 1966.

Fig. 27. Saint Mark, Ebbo Gospels, 816-35, Èpernay, Bibliothèque Municipale, MS I, fol. 60v.

Fig. 28. John the Evangelist, Byzantine Gospel Manuscript (Luke and John), Constantinople, late 12th c., Washington, D. C., Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collections, Dumbarton Oaks Acc. no. 74.1, fol. 150v.

Fig. 29. Christ in Majesty, Tahull, San Clemente, Apse Fresco, detail, ca. 1100, ©MNAC—Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona.

Fig. 30. Ascension, Sacramentary of the Cathedral of Saint Étienne of Limoges, ca. 1100, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, MS lat. 9438, fol. 84v.

Fig. 31. Initial to Micah, Winchester Bible, late 12th c., Winchester Cathedral Library, fol. 205 (The Dean and Chapter of Winchester/Winchester Cathedral Library).

Fig. 32. The Sower among Thorns, north choir aisle window n. XV,8, Canterbury Cathedral, ca. 1180, detail (photograph by author).

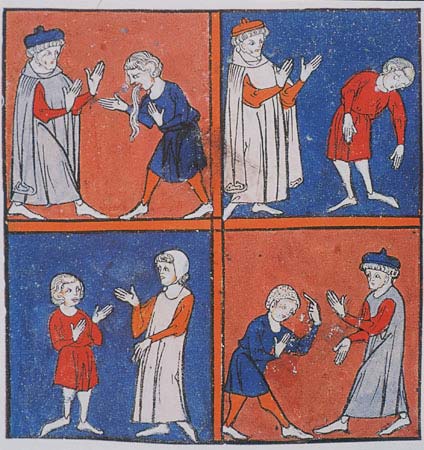

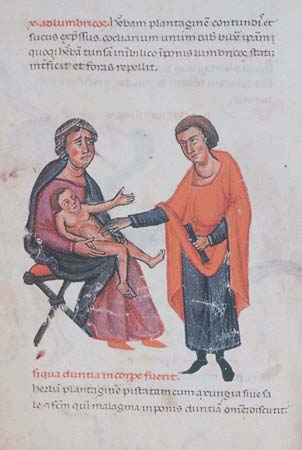

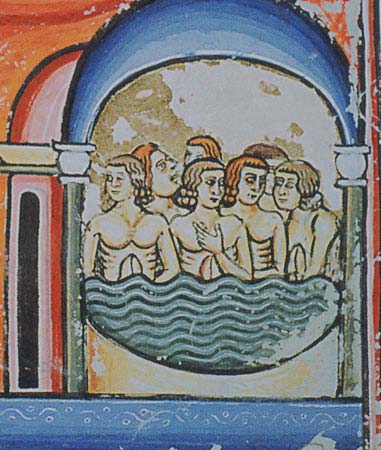

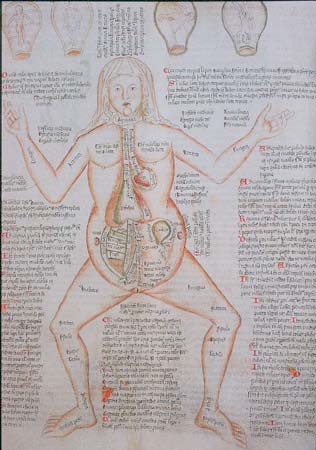

Next, in a sequence of paired images I can establish that there was a very broad change in visual representation, and establish when it occurred.[35] My first examples are from medical manuscripts. In an eleventh-century Byzantine book with a commentary on Hippocrates, the nude figures are quite dark, and evidently still owe much to an ancient Greek or Roman prototype (Figure 33).[36] A fourteenth-century book from France, showing a sequence of physician-patient interactions, forms a very marked contrast. Here all the faces and hands are opaque white, and the hair very light (Figure 34).[37] Two south Italian medical works, from the 12th and the 13th centuries, also provide a contrast in the depiction of bare skin. The earlier artists still adhered to rich flesh tints giving ruddy complexions, and variously black or brown hair (Figure 35). By the second half of the thirteenth century this coloration had changed dramatically: In scenes of bathing in Peter of Eboli’s tract on the curative baths at Pozzuoli the artist exposes pure white bodies and gold or red hair (Figure 36).[38] These examples in medical manuscripts are of particular interest because there is no reason for them to be impacted by theological ideas that elided the good with light and purity.[39] Even if the healthful body would be regarded as “beautiful” in the sense of honestum – usefulness – that the scholastics used alongside beauty (pulchritudo), the question of whiteness does not necessarily enter in; in fact to be pallid was long recognized as a sign of ill health, as now in the phrase “dead white.”

In other contexts, whiteness had a different significance. In the later Middle Ages, saints in paradise gleam as white as their garments, like this fourteenth-century Saint John from York Minster (Figure 37). By then it had become the norm for glass-painters to use colorless glass instead of flesh tints. Blond hair was colored golden-yellow by a new technique employing silver oxide. The bodies of the saints as represented in their reliquaries had incorruptible casings, precious materials replacing the porous dermic boundaries of the living body. A virginal saint might be celebrated in enamels, with a pearly complexion and “pure” white garment (Figure 38). At some stage, Christians appropriated something of this sanctity by depicting their kind as truly “white.”

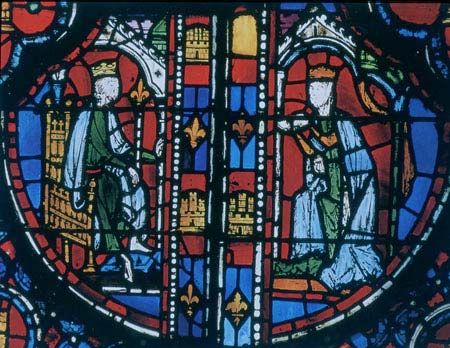

In fact I believe we can pinpoint the shift to a preference for “white people” to France in the reign of Louis IX. The artists of the Psalter made for his grandfather’s queen, Ingeborg of Denmark, about 1195 modeled flesh in tones of pink and brown (Figure 39). Forty years later his mother, Blanche of Castile who ruled during his minority, had much lighter figures painted in her Psalter (Figure 40). The glass Louis IX and Blanche had painted in the 1240s for the palace chapel in Paris, the famous Sainte Chapelle, used colorless or barely tinted glass for the faces, and this became the norm (Figures 41, 42).[40] Louis’ own Psalter followed suit about 1255-70.[41] The mid-century glass painters had also introduced a radically simplified facial type, scarcely modeled at all, and with a tiny nose and mouth and pale brown hair; there was no silver stain yet (Figure 43). There is no variation in facial expression – as if the figures are constrained by decorum.[42] Such monotonous white figures could be contrasted with grimacing darker-skinned people, with large noses or flaring nostrils. For an older generation of art historians the predominant new complexion and facial type appeared to be no more significant than other stylistic changes, in accord with their notions of a Gothic era. I view it as a dramatic change in representational code, with broad ramifications.

The coincidence of this chromatic shift with the reign of Louis IX is a startling discovery, yet it should be no surprise. North Europeans were walking very tall – the Holy Roman Empire stretched from Sicily to the Baltic (where the tribes had just been converted by the Knights of the Cross); and the Roman Church had just asserted significantly greater control over the laity at the Lateran Council of 1215. In France the tallest buildings in the world were under construction, using radically new engineering concepts. Louis IX was the crusader king par excellence, canonized very soon after his death on crusade in 1270.[43] And following after the dowager queen Blanche of Castille, every generation of Capetians had numerous Blanches and Marguerites (the latter of course being a white daisy).

Fig. 33. Physician and patient, Byzantine Manuscript of the Commentary of Apollonius of Citium on the De articulis of Hippocrates, 11th c., Florence, Biblioteca Laurenzina, MS Plut. 74.5, fol. 195v (By permission per I Beni e le Attività Culturali).

Fig. 34. Consultations between doctor and patient, Medicinal, 14th c., British Library, Sloane MS 1977, fol. 50v.

Fig. 35. Physician and child, Pseudo- Apuleius, Herbal, 12th c., Florence, Biblioteca Laurenziana, MS Laur. Plut. 73.16, fol. 29v (By permission of the Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali).

Fig. 36. Bathers, Peter of Eboli, de balneis Puteolanis, 13th c., Rome, Biblioteca Angelica, MS 1474, fol. 12 (By permission of the Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali).

Fig. 37. Saint John, west window, York Minster, ca. 1340, detail (© Crown Copyright. National Monuments Record).

Fig. 38. Saint Catherine of Alexandria, reliquary, 1400, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 17.190.905.

Fig. 39. The Deposition, The Ingeborg Psalter, ca. 1195, detail, Chantilly, Musée Condé, MS 1695, fol. 27 (photograph provided by Florens Deuchler).

Fig. 40. Crucifixion and Deposition, Psalter of Blanch of Castile, ca. 1230, Paris, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, MS franc. 1186, fol. 24.

Fig. 41. Esther Window, Sainte Chapelle, Paris, 1240-49, details (©Bernard Acloque, CMN [Centre des Monuments Nationaux]).

Fig. 42. Esther Window, Sainte Chapelle, Paris, 1240-49, details (©Bernard Acloque, CMN [Centre des Monuments Nationaux]).

Fig. 43. Fragment of stained glass perhaps from Soissons Cathedral, ca. 1250, formerly in a New England Collection, now London, Victoria and Albert Museum (photograph provided by author).

Fig. 44. Judgment of black captives, Feudal Customs of Aragon, ca. 1290-1310, detail, Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, MS Ludwig XIV 6, fol. 244.

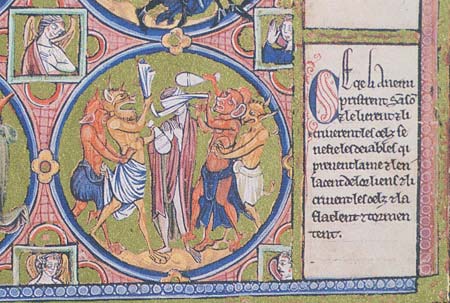

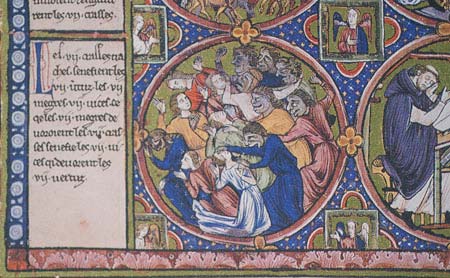

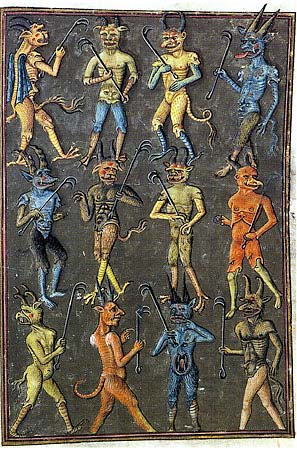

One reason that European Christians had come to regard themselves as white by 1250 may be that they had been coming in contact in large numbers with brown infidels, and with the sub-Saharan Africans who had been enslaved by Moslems.[44] For example, we see black captives brought before the Christian king in a Spanish manuscript (Figure 44).[45] There are records of black so-called Ethiopians even in the north. In his autobiography, Guibert of Nogent tells of the fear inspired in the community of Laon in 1112 by an immense baptized Ethiopian hangman in the service of Bishop Gaudri, and it became common to represent one or more of the flagellants of Christ as black.[46] A formidable dark, grimacing figure executes a snow-white Saint Lucy in a late thirteenth-century book that belonged to a Madame Marie, and the brownish tones that were the normal flesh color in the Psalter of Queen Ingeborg were used in this later book for a Jewish tormentor of Christ who emerges behind the good (white) thief; the sponge-bearer’s conical hat shows he is not represented as a Roman (Figures 45, 46, 47). The color-coding conveniently elided with an old association of black with the devil.[47] In an important early thirteenth- century moralized bible, of which one recension was certainly made for Blanche and Louis about 1230, colored devils not only contrast with very white believers, but “bad” Jews tend to be dark skinned (Figures 48, 49).[48] They constitute the bad and the ugly. Vari-colored devils became the norm by the later middle ages — black, brown, yellow, and red (Figure 50).[49] They anticipate the strange designations given by European conquerors and colonizers to “red” Indians, and “yellow” Asians – and more recently, green Martians. But first, Jews in a fifteenth century German chronicle were depicted as red (Figure 51). This fully developed chromophobia needed only a few more strange peoples to feed on in order to encompass racism.[50]

The invention of white identity is an ominous notion, given later histories of colonization and ethnic cleansing. In western culture, the good promised vengeance against the ugly and the evil, whether God Almighty presiding over the Last Judgment of Amiens Cathedral or Blondie ready to spike a canon in “Indian country” (Figure 52)[51] Between the two images is an unbroken tradition associating the white with the Good. Yet like all hegemonic systems, it immediately oppressed some members of the ruling group as well as other groups that were overtly oppressed.[52]

In order to understand such conflicts, three aspects of performative identification especially deserve noting: One is that the tortured bodies of Christ and the saints maintained the myth of Christian persecution at the hands of non-believers, so a dangerous paranoia was fostered in the viewing community. The Huns attacking Saint Ursula and her followers on the Rhine are represented as dark Saracens in the Picture Book of Madame Marie (Figure 53). In fact around 1250 no recent saints had been killed by infidels – the most recent martyr, Thomas Becket, was struck down by agents of his white English king in 1170. But as we have seen, the stage for Louis IX’s death on crusade (albeit from sickness) had been set by preceding representational codes.

Secondly, a major part of paranoia is anger turned against the supposed attacker. In flagellation and crucifixion scenes such as those in the Book of Madame Marie or the Ramsey Psalter, Christ’s body glowed white like the Eucharist, which the Lateran Council of 1215 declared to be the actual body of Christ (Figures 54, 55). An industry arose in special vessels and locked tabernacles to prevent desecration of the consecrated bread and wine, and by 1317 a new universal feast day celebrated the cult of the Eucharistic body of Christ (Corpus Christi). Meanwhile, accusations against Jews who were said to have desecrated the host led to countless incidents of violence against them, and even pogroms throughout the later middle ages.[53] In Paolo Uccello’s famous fifteenth-century predella paintings of such an incident, a Christian woman exchanges a Eucharistic wafer for a garment proffered by a Jewish pawnbroker, who tries to cook it in his home (it is seen bleeding in the chimney nook). He and his wife and children are led away and burned (Figure 56).[54]

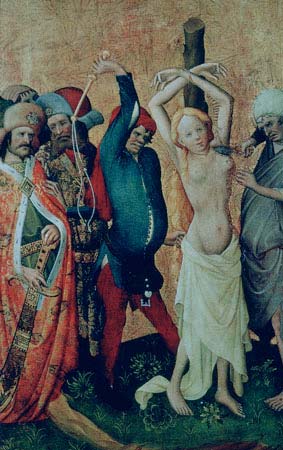

A third aspect of the new color-coding may have had a detrimental impact on women among white Christians, through an over-protectiveness that also stems from paranoia: White women, like Tuco’s victim, have been given special protection from rape or abduction, real or imagined, by non-whites.[55] The men who ogle the pale tortured body of Saint Barbara in Meister Franke’s famous altarpiece of around 1400 are given darker skin and exotic clothing – even though one is her father (Figure 57).[56] There were earlier popular legends of crusading heroes falling in love with the beautiful white daughter of black Saracens, and persuading her to betray them before converting to Christianity.[57] Roman history was also sometimes pictured in such polarized terms. In a late fifteenth- century Flemish manuscript of the Roman de la Rose, Nero’s wickedness shows in his ruddy countenance as he orders the physicians to cut his mother, Agrippina, open in order to see where he came from. She is as innocent and pure white as the martyred saints in thirteenth-century representations (Figure 58).[58])

Fig. 45. Execution of Saint Lucy, Le Livre d’images of Madame Marie, ca. 1300, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, MS n. a. fr. 16251, fol. 99v.

Fig. 46. Crucifixion, Le Livre d’images of Madame Marie, ca. 1300, detail, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, MS n. a. fr. 16251, fol. 38.

Fig. 47. The Deposition, The Ingeborg Psalter, ca. 1195.

Fig. 48. Devils and Monks, Bible moralisée (Samson cycle), 13th c., detail, Vienna, Austrian National Library, Codex Vondobonensis 2554, fol. 63A.

Fig. 49. Vices, Bible moralisée (Joseph cycle), 13th c., Vienna, Austrian National Library, Codex Vindobonensis, fol. 10v (above right).

Fig. 50. Colored devils, ca. 1450-70, Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Douce 134, fol. 99 (above left).

Fig. 51. Red Jews, Uffenbachsches Wappenbuch, ca. 1400-10, Strasbourg, Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Hamburg, Cod. 90 B in scrin., fol. 51.

Fig. 52. Joe (“Blondie”), the Good, with cannon, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, film still, 1966.

Fig. 53. Martyrdom of Saint Ursula, Le Livre d’images of Madame Marie, ca. 1300, Paris, Bibliothéque Nationale de France, MS n. a. fr. 16251, fol. 101v.

Fig. 54. Crucifixion, Le Livre d’images of Madame Marie, ca. 1300, detail, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, MS n. a. fr. 16251, fol. 38.

Fig. 55. Crucifixion Scenes, East Anglia or London, ca. 1300-10, New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, MS M 302, fol. 3 (left).

Fig. 56. Paolo Uccello, Host Desecration and Discovery, predella to Altarpiece of the Communion of the Apostles, 1465-68, Urbino, Palazzo Ducale (below).

Fig. 57. Meister Franke, Torture of Saint Barbara as Directed by her Father (left), Saint Barabara Altarpiece, ca. 1400, Helsinki.

Fig. 58. Nero and his Mother, Agrippina, Roman de la Rose, Belgium, ca. 1500, London, British Library, Harley MS 4425, fol. 59.

Yet such “white” women suffered from the ignorance of their bodies that was perpetuated by this fear of autopsy, or of understanding their bodies scientifically. In an early fifteenth-century illustration to the Gynaecia of Moschion, there is a fair amount of ancient nonsense written around a rendering of a veiled but otherwise naked white woman who is a site of diseases, and a purse to hold a fetus; not only does she have a uterus denoted embrio but four enlarged uteri above her head demonstrate fetal positions (Figure 59).[59] The veil of a married woman legitimates her pregnancy. Yet one of the most influential gynecological texts of the thirteenth-century, the Secrets of Women by a Dominican in the circle of Albertus Magnus, has little concern for birthing (which he would not have been allowed to see) but warns that intercourse with menstruating women can produce leprosy in the offspring of the union, and that monsters should not be painted in the bed chamber because if a woman looked at them during coitus she would give birth to a monster.[60]

Evidently, gynophobia went along with chromophobia, as recognized in the women’s studies mantra, race, class, gender. In appropriating the lighter complexion that had been accorded to women up to the end of the twelfth century, European Christian men maintained their gendered hegemony by abjectifying women’s generative power, while objectifying the bodily characteristics of other peoples. They had invented the Whiteman.

Fig. 59. Disease Woman, Wellcome Apocalypse, 15th c. Wellcome MS 49, fol. 38.

Madeline Harrison Caviness is Mary Richardson Professor Emeritus in the Department of Art and Art History at Tufts University, where she has taught since 1981. She is also the former president of the Union Académique Internationale, the Conseil International pour la Philosophie et des Sciences Humaines (CIPSH, an affiliate of UNESCO), the Corpus Vitrearum International Board, the Medieval Academy of America, and the International Center of Medieval Art. Her work focuses on such issues as obscenity, gender and sexuality, iconoclasm, skin color and “racism,” historiography and theory. She is the author of over ninety articles on medieval art, as well as one on modern art, and has published numerous books, most recently Visualizing Women in the Middle Ages: Sight, Spectacle and Scopic Economy (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), Medieval Art in the West and its Audience (Variorum Reprints, 2001), and her e-book, Reframing Medieval Art: Difference, Margins, Boundaries (Tufts University, 2001, http://dca.lib.tufts.edu/Caviness). She was recently collaborating with Charles Nelson on a book examining the representation of women and Jews in the German law book known as the Sachenspiegel (Saxon Mirror).

References

| ↑1 | I gave the first version of this paper as the Plenary opening address at the First International Congress on the Humanities, Riga, Oct. 2005; it is in press as Madeline H. Caviness, “The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly,” Letonikas Primais Kongress 3: Filozofi, ed. Maija Kule (Riga: Latvijas Zin_t_u Akadémija, c2006), 179-90, 473-88. I expanded the presentation for the Medieval Academy of America Plenary Lecture, “The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly,” at the Medieval Congress in Kalamazoo in May 2006, the conference in which other articles in this issue were given as papers. I am grateful to the audiences at both venues, and elsewhere, for enthusiastic responses and questions that have helped to shape this version. I am additionally grateful to research assistant Jennifer Lyons for help with identifying image sources and keeping track of licensing agreements. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Among many recent studies of the demonic: Jeffrey Burton Russell, Lucifer: The Devil in the Middle Ages (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1984); Victor Beyer, “La démonologie à la cathédrale de Strasbourg,” Bulletin de la cathédrale de Strasbourg XXII (1996), 19-34; Dyan Elliott, Fallen Bodies. Pollution, Sexuality, and Demonology in the Middle Ages, (The Middle Ages Series), eds. Ruth Mazo Karras and Edward Peters (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999); Debra Higgs Strickland, Saracens, Demons, and Jews: Making Monsters in Medieval Art (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003); Nancy Caciola, Discerning Spirits: Divine and Demonic Possession in the Middle Ages, Conjunctions of Religion and Power in the Medieval Past (Ithaca, N.Y., London: Cornell University Press, 2003); Deborah Kahn, “Saint Augustin et le diable, à propros dun chapiteau de Moutiers-Saint-Jean,” Bulletin monumental: Société française d’archéologie 162.3 (2004): 189-92. |

| ↑3 | Madeline H. Caviness, “Images of Divine Order and the Third Mode of Seeing,” Gesta XXII.2 (1983): 99-120. https://doi.org/10.2307/766920; reprinted in Madeline H. Caviness, Art in the Medieval West and its Audience, Variorum Collected Studies, vol. 718 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2001), ch. 2. |

| ↑4 | Umberto. Eco, Art and Beauty in the Middle Ages, trans. Hugh Bredin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986), 9-11. |

| ↑5 | Eco, Art and Beauty 28., citing Saint Augustine, Letter 3 (to Nebridius), Letters, vol. 1, tr. Sister Wilfred Parsons (Washington, 1951), 6-11 (here 9), and Cicero, Tusculum Disputationes, tr. J. E. King (London and Cambridge, 1950), IV, 13[sic]. For the original texts: Patrologia Latina, (full text database), vol. 33, col. 65, Augustinus Hipponensis, Epistola III: “Quid laudant in corpore? Nihil aliud video quam pulchritudinem. Quid est corporis pulchritude? Congruentia partium cum quadam coloris suavitate;” c.f. M.Tulli Ciceronis Tusculanae disputations, ed. Michaelangelus Giusta, (Turin 1984), 227: IV, 31: “Et ut corporis est quaedam apta figura membrorum cum coloris quaedam suauitate eaque dicitur pulcheritudo.” |

| ↑6 | Eco, Art and Beauty 35, 58. |

| ↑7 | My friend and colleague Charles G. Nelson in the Department of German at Tufts University has long used a course on Grimms’ Fairy Tales to teach students to examine ideologies of gender and class. |

| ↑8 | Many stills are available online at Internet Movie Database Inc.: http://www.imdb.com/tt0060196. |

| ↑9 | Christopher Frayling, Once Upon a Time in Italy: The Westerns of Sergio Leone (New York: Abrams, 2005). I am grateful to my colleague Adriana Zavala for the loan of this book. |

| ↑10 | This particular gesture, when a male chucks the chin of a female, is a sign for attempted sexual seduction in high medieval art: Linda Seidel, “Salome and the Canons,” Women’s Studies 11 (1984): 29-66. See also its use in the early fourteenth-century upper Rhenish Manesse Codex: Ingo F. Walther and Gisela Siebert, eds., Codex Manesse: Die Miniaturen der Großen Heidelberger Liederhandschrift (Frankfurt am Main: Insel, 1988)., pl. 29 (Heidelburg, Universitätsbibliothek Cod. 848, f. 69). |

| ↑11 | C. Stephen Jaeger, “Appendix A. Moral Discipline and Gothic Sculpture: The Wise and Foolish Virgins of Strassburg Cathedral,” The Envy of Angels: Cathedral Schools and Social Ideals in Medieval Europe, 950-1200 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1994) 331-48, 476-78. https://doi.org/10.9783/9780812200300.331 |

| ↑12 | For the prostitutes who seduce the Prodigal Son, as represented in a stained glass window at Chartres, see Madeline H. Caviness, Visualizing Women in the Middle Ages: Sight, Spectacle, and Scopic Economy, The Middle Ages Series, ed. Ruth Mazo Karras (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001) 10-14, figure 9. In the early 13th century prostitutes were required to wear a distinguishing mark or color (often yellow). Their dress here accords with the sumptuary laws that at times exempted street women from the ban on finery that pertained to decent women, as demonstrated by Amy Cottrill, “Undressing the art of the high middle ages: clothing as a communicative tool in French and German art of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries” (M. A. Thesis, Tufts University, 1998), 63, citing Alan Hunt, Governance of the Consuming Passions: A Short History of the Sumptuary Laws (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996) 241-43. For such changes in proscribed dress, see Françoise Piponnier and Perrine Mane, Dress in the Middle Ages, trans. Caroline Beamish (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997). 139-141. For sumptuary laws that penalized prostitutes for wearing furs etc., see Ruth Mazo Karras, “”Because the Other is a Poor Woman She Shall Be Called His Wench”: Gender, Sexuality, and Social Status in Late Medieval England,” Gender and Difference in the Middle Ages, eds. Sharon Farmer and Carol Braun Pasternack, vol. 32, Medieval Cultures (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003) 214-15. |

| ↑13 | The biblical Delilah, and many nameless wives (Lot’s, Job’s, Potiphar’s) are other examples. |

| ↑14 | Frayling, Once Upon a Time, 111. |

| ↑15 | Baruch Gitlis, “Redemption” of Ahasuerus: The “Eternal Jew” in Nazi Film, trans. Norman Berdichevsky (Astoria, NY: Holmfirth Books, 1991) 113-42. The stills of Jews from the Warsaw ghetto were faded into the same faces without their beards, made sinister and unstable (131, 138). The film stills give some idea of the expressions, especially pages 122, 125, 126. |

| ↑16 | For Bosch’s painting of Christ Bearing the Cross in Ghent, the Museum voor Schone Kunsten, and other examples, see: James Marrow, “Circumdederunt me canes multi: Christ’s Tormentors in Northern European Art of the Late Middle Ages and Early Renaissance,” The Art Bulletin, 59 (1977): 178, Figure 29. https://doi.org/10.2307/3049628 |

| ↑17 | Gitlis, “Redemption” of Ahasuerus: The “Eternal Jew” in Nazi Film 115-16. |

| ↑18 | Alison Stones, Le livre d’images de Madame Marie: reproduction intégrale du manuscrit Nouvelles acquisitions françaises 16251 de la Bibliothèque nationale de France (Paris: Editions du Cerf: Bibliothèque nationale de France, 1997). |

| ↑19 | Walter Cahn and Linda Seidel, Romanesque Sculpture in American Collections, I: New England Museums, International Center for Medieval Art, 1st ed., vol. 1 (New York: Burt Franklin & Co., 1979) 105, Figure 04. |

| ↑20 | Madrid, El Escorial, Real Biblioteca de San Lorenzo, Cod. T.I,1, Cantiga clxxxvi Jean Devisse, The Image of the Black in Western Art, from the Early Christian Era to the ‘Age of Discovery’: From the Demonic Threat to the Incarnation of Sainthood, trans. William Granger Ryan, vol. II/1 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1976) 87, Pl. 50. The manuscript dates between 1252 and 1284. Under Islamic law, the Mudejar of Spain punished their own women accused of adultery or interfaith sex, with death: David Nirenberg, “Muslims in Christian Iberia,” The Medieval World, eds. Peter Linehan and Janet L. Nelson (London: Routledge, 2001) 72. |

| ↑21 | I none the less owe a great debt to the instigators of post-colonial theory, notably Edward Said and Gayatri Spivak; see: Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths and Helen Tiffin, eds., The Post-Colonial Studies Reader, 2002 ed. (London: Routledge)., and Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, ed., The Postcolonial Middle Ages (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000). |

| ↑22 | A decade ago a panel at the International Medieval Congress in Kalamazoo, Michigan, gave rise to a very substantial group of papers that purport to examine medieval definitions of “racial” difference. The papers were later published in Thomas Hahn, ed., Race and Ethnicity in the Middle Ages, vol. 31/1 (2001). The authors concentrate most often on literary and visual representations of black people, though there is also very useful attention to the tendency in the high Middle Ages to enumerate many different European and Christian “races” (gentes) defined by customs and language (e.g. pages 7, 160). When “white” identity is invoked by medieval authors, it is often in relation to black, but these essayists do not interrogate the meanings of whiteness, thus naturalizing it (eg. pages 5, 13, 19, 20, 24, 57, 68, 87, 116, 119). They fall into the trap of the very “textual inscription of ethnographic subjectivity” that Lomperis critiques in Mandeville’s Travels: Linda Lomperis, “Medieval Travel Writing and the Question of Race,” The Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 31 (2001).: 147-164 Nonetheless, I will have occasion to rely on these authors at several junctures below. |

| ↑23 | “Introduction” in Peter Linehan and Janet L. Nelson, eds., The Medieval World (London: Routledge, 2001) 13. |

| ↑24 | It could however be noted that in the 12th-13th century romances and love poems the typical description of beautiful young nobles, especially women but also knights, includes a pale skin and rosy cheeks and lips. |

| ↑25 | Pakistan Forum, Dear Mzungu-Dear White Man. http://www.paktribune.com/pforums/posts.php?t=2324&start=1 The term “mzungu” for white man originated in the Kinyarwandi and Kurundi languages of Tanzania, and occurs also in Kiswahili. Among anthropologists who questioned the notion of a “white”or “Caucasian” European race, preferring to use a color scale to describe skin color, were Hans F. K. Günther and Gerald Clair William Camden Wheeler, The Racial Elements of European History (New York: E. P. Dutton and company, 1927) 1-2. His definitions, however, were fraught with other problems. |

| ↑26 | Devisse, Image of the Black: Demonic to Sainthood.; Jean Devisse and Michel Mollat, The Image of the Black in Western Art, from the Early Christian Era to the ‘Age of Discovery’: Africans in the Christian Ordinance of the World ((Fourteenth to the Sixteenth Century), trans. William Granger Ryan, vol. II/2 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979).; Paul H. D. Kaplan, The Rise of the Black Magus in Western Art, Studies in the Fine Arts: Iconography, ed. Linda Seidel, vol. 10 (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1985).; Gude Suckale-Redlefsen, Mauritius: Der heilige Mohr: The Black Saint Maurice (Houston and Zurich: Menil Foundation and Schnell & Steiner, 1987).; Paul H. D. Kaplan, “Black Africans in Hohenstaufen Iconography,” Gesta 26.1 (1987): 29-36. |

| ↑27 | In order to make the general statements that follow, I perused many slides and the plates in many art books; I also re- tested my hypothesis while visiting an exhibition of manuscripts: The Splendor of the Word, Medieval and Renaissance Illuminated Manuscripts at The New York Public Library (October 21 2005-February 12 2006) New York 2005. The label for #55, a late fourteenth-century book of hours from Avignon, even referred to the “luminous grey-white flesh tone.” Only two works of the 13th – 14th centuries used pinker tones: # 9 & 28, from England and Germany respectively. |

| ↑28 | Among many sources I looked through, the color plates in Henry Luttikhuizen and Dorothy Verkerk, Snyder’s Medieval Art (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1989, 2006) 61-318, bear this out, with very few exceptions. |

| ↑29 | Luttikhuizen and Verkerk, Snyder’s. Figures 13.6 (apse of S Climente of Tahull, c 1100) and 13.6 (Sacramentary from St. Etienne of Limoges, c 1100). |

| ↑30 | Claire Donovan, The Winchester Bible, 1st ed. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993)., Luttikhuizen and Verkerk, Snyder’s Figure 9.6.; Devisse, Image of the Black: Demonic to Sainthood Figures 24,25. |

| ↑31 | The sower is from the late twelfth century typological windows of the choir: Madeline H. Caviness, The Windows of Christ Church Cathedral, Canterbury, Corpus Vitrearum Medii Aevi, Great Britain 2, vol. 2 (London: Oxford University Press for the British Academy, 1981) 122. Also compare Pls. VII and XVI: the faces in the Trinity Chapel glass of the 1190s to 1220 are colorless or very pale pink. Donovan, The Winchester Bible, Luttikhuizen and Verkerk, Snyder’s, Figure 9.6.; Devisse, Image of the Black: Demonic to Sainthood, Figures 24, 25. |

| ↑32 | Madeline H. Caviness, Stained Glass Windows, (Typologie des Sources du Moyen Age Occidental 76) (Tournhout: Brepols, 1996) 51-52, Figure 1. |

| ↑33 | Manganese is unique among colorants used in stained glass in that it is subject to slight darkening when exposed to sunlight; thus, some of the faces at Canterbury may be a shade darker than when they left the hands of the painter, but the distinction from lighter complexions in the same windows still holds. |

| ↑34 | Cited by Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, “On Saracen Enjoyment: Some Fantasies of Race in Late Medieval France and England,” The Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 31: 118. and Robert Bartlett, “Medieval and Modern Concepts of Race and Ethnicity,” The Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 31 (2001): 46. https://doi.org/10.1215/10829636-31-1-113 |

| ↑35 | A recent location of the transition from pagan Roman notions of black people to Christian encoding of them as morally tainted, in the sixth-century Ashburnham Pentateuch, does not deal with the issue that non-black complexions are very varied, despite the promising remark that “the depiction of blacks . .. was necessary to construct a white and Christian identity:” Dorothy Hoogland Verkerk, “Black Servant, Black Demon: Color Ideology in the Ashburnham Pentateuch,” The Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 31 (2001): 57. https://doi.org/10.1215/10829636-31-1-57 |

| ↑36 | Commentray of Apollonius, Florence, Biblioteca Laurentiana Plut. 74.7 f. 195v. For this and other examples, see: Peter Murray Jones, Medieval Medicine in Illuminated Manuscripts (London and Milan, Italy: The British Library & Centro Tibaldi, 1998). I refer specifically to Figures 17 cf 42. |

| ↑37 | Jones, Medieval Medicine. Figure 42: Sloane MS 1977 f. 50v. |

| ↑38 | Peter of Eboli de balneis Puteolanis ,thirteenth century, Italy. Jones, Medieval Medicine, Figure 96. |

| ↑39 | The early development of such ideas is usefully traced by Verkerk, “Black Servant.” Even though Wolfram von Eschenbach destabilizes the trope in Parzival (ca. 1200) , to describe the black Moslem queen Belcane as : “a judge of fair complexions, for she had seen many a fair-skinned heathen (=Christian) before,” the term lieht carries the connotation of light and bright: Thomas Hahn, “The Difference the Middle Ages Makes: Color and Race before the Modern World,” The Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 31 (2001): 16-17. I am grateful to my colleague Charles G. Nelson for his insights into the original wording. https://doi.org/10.1215/10829636-31-1-1 |

| ↑40 | The color plates in Jean-Michel Leniaud and Françoise Perrot, La Sainte Chapelle (Paris: Nathan/Caisse Nationale des Monuments Historiques et des Sites, 1991) 126-208. give a good indication of this practice, though the authenticity of individual figures still has to be judged from the restoration charts in L. Grodecki, J. Lafond and et al., Les Vitraux de Notre-Dame et de la Sainte Chapelle de Paris, Corpus Vitrearum Medii Aevi, France (Paris: 1959). |

| ↑41 | Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, MS lat 10525: Luttikhuizen and Verkerk, Snyder’s Figure 17.9. |

| ↑42 | Aly Jordan has demonstrated the extent to which the overall compositions obeyed the rules of poetics and rhetoric current at the time: Alyce Jordan, Visualizing Kingship in the Windows of the Sainte-Chapelle (Turnhout: Brepols Publishers for the International Center for Medieval Art, 2002). |

| ↑43 | Jacques Le Goff, Saint Louis, Bibliothèque des Histoires (Paris: Gallimard, 1996).; Daniel Weiss, Art and Crusade in the Age of Saint Louis (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998).; Laura H. Hollengreen, “The Politics and Poetics of Possession: Saint Louis, the Jews, and Old Testament Violence,” Between the Picture and the Word: Manuscript Studies from the Index of Christian Art, ed. Colum Hourihane (Princeton: Index of Christian Art, 2005), 51-71. |

| ↑44 | Charles Verlinden, “Blacks,” Dictionary of the Middle Ages, ed. Joseph R. Strayer, vol. 2 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1983).; Also Steven A. Epstein, Speaking of Slavery: Color, Ethnicity, and Human Bondage in Italy (Conjunctions of Religion and Power in the Medieval Past) (Ithaca, N. Y. and London: Cornell University Press, 2001). Especially pertinent is his account of the Christian distinction between black slaves and white captives, pages 192-197, color plate facing page 192. |

| ↑45 | The historical and pictorial examples that follow are from: Devisse, Image of the Black: Demonic to Sainthood. |

| ↑46 | Suckale-Redlefsen, Mauritius: Der heilige Mohr: The Black Saint Maurice, 21. She illustrates the executioner of John the Baptist in the Great Canterbury Psalter of 1190-1210, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, MS lat 8846 f. 2v. Also, there are many black flagellants of Christ, as in the Psalter Henry of Winchester, and the Sens Cathedral Good Samaritan window. |

| ↑47 | In a binary pattern of demonization and idealization, there was also an important cult of the Black Madonna and Child, especially in southern Europe: Madeline H. Caviness, “(Ex)Changing Colors: Queens of Sheba and Black Madonnas,” Architektur und Monumentalskulptur des 12.-14. Jahrhunderts. Produktion und Rezeption. Festschrift für Peter Kurmann zum 65. Geburtstag; Architecture et sculpture monumentale du 12e au 14e siècle. Production et réception. Mélanges offerts à Peter Kurmann à l’occasion de son soixante-cinquième anniversaire, ed. Stephen Gasser, Christian Freigang and Bruno Boerner (Bern; Berlin; Bruxelles; Frankfurt am Main; New York; Oxford; Wien: Peter Lang, 2006) 553-70. Useful studies not referenced there are: Jean Pierre Bayard, Déesses mères et vierges noires: répretoire des vierges noires par département (Monaco: Rocher, 2001).; Sophie Cassagnes-Brouquet, Vierges noires (Rodez: Éditions du Rouergue, 2000).; F. Vialet; B. Gourtay, Iconographie de la Vierge noire du Puy (Baptistère Saint-Jean, Exposition) (Le Puy: Départment de Haute-Loire, 1983). |

| ↑48 | Gerald B. Guest, Bible Moralisée. Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Cod. Vind. 2554 (London: Harvey Miller, 1995)., especially the demonic attackers on ff. 10v and 44v. |

| ↑49 | Vivid examples of later colored devils are in Herman Pleij, Colors Demonic and Divine: Shades of Meaning in the Middle Ages and After, trans. Diane Webb (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004)., pls. 17, 18. |

| ↑50 | A few years ago in a College Art Association discussion panel I heard David Batchelor, a YBA (Young British Artist) use the term “chromophobia” for westerners’ “searching for comfort in whiteness.” |

| ↑51 | Denis Verret and Delphine Steyaert, eds., La Couleur et la Pierre: Polychromie des portails gothiques: Actes du colloque, 2000 (Paris/Amiens: Picard/Agence régionale du Patrimoine de Picardie). |

| ↑52 | I emphasize in my courses on gender that “The oppressor is also oppressed in systems of oppression.” A useful example is in the risk to life and limb of high-born men in a culture that heroized combat and used the ideology of conquest to oppress Others. |

| ↑53 | For a general survey of deteriorating Christian-Jewish relations, Anna Sapir Abulafia, “Christians and Jews in the High Middle Ages: Christian Views of Jews,” in Christoph Cluse, The Jews of Europe in the Middle Ages (Tenth to Fifteenth Centuries) Proceedings of the International Symposium held at Speyer, 20-25 October 2002, Cultural Encounters in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, vol. 4 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2004) 20-27. Specific instances are detailed by Michael Toch, “The Formation of a Diaspora: The Settlement of Jews in the Medieval German Reich,” Peasants and Jews in Medieval Germany: Studies in Cultural, Social and Economic History, (Aldershot, GB, Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2003) 68-69., and by Friedrich Lotter, “Die Judenverfolgungen des “König Rintfleisch” in Franken um 1298. Die endgültige Wende in den christlich-jüdischen Beziehungen im Deutschen Reich des Mittelalters,” Zeitschrift für Historiche Forschung (1988), 385-422. |

| ↑54 | Miri Rubin, Gentile Tales: The Narrative Assault on Late Medieval Jews (New Haven, CN, and London: Yale University Press, 1999), 144-145, Figure 16. The Christian woman was hanged, but her soul was saved. |

| ↑55 | Vron Ware, Beyond the Pale: White Women, Racism and History (London and New York: Verso, 1992). |

| ↑56 | For a discussion of the sado-erotic aspects of this painting, see: Caviness, Visualizing Women, 115-16, Figures 52-53. |

| ↑57 | Jacqueline de Weever, Sheba’s Daughters: Whitening and Demonizing the Saracen Woman in Medieval French Epic, Garland Reference Library of the Humanities, vol. 2077 (New York: Garland, 1998). |

| ↑58 | London, British Library, Harley MS 4425, f. 59. Jones, Medieval Medicine. Figure 31.; an early fourteenth-century manuscript, however, shows all the actors in this scene with parchment-colored skin (ibid. Figure 30 |

| ↑59 | Wellcome Apocalypse, London,Wellcome Library, MS 49, f. 38. Jones, Medieval Medicine. Figure 22. See now the excellent website for many pages in the manuscript: http://library.wellcome.ac.uk/ttp.html. |

| ↑60 | Helen Rodnite Lemay, Women’s Secrets. A Translation of Pseudo-Albertus Magnus’s “De Secretis Mulierum” with Commentaries (Saratoga Springs, N. Y.: State University of New York Press, 1992), 115-16. |