Kathleen Biddick • Temple University

Madeline Caviness • Tufts University

Recommended citation: Kathleen Biddick and Madeline Caviness, “Inter-View with Madeline Caviness, March 31, 2006,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 1 (2008). https://doi.org/10.61302/BAIY4782

Topic: Girls Just Want to be Girls

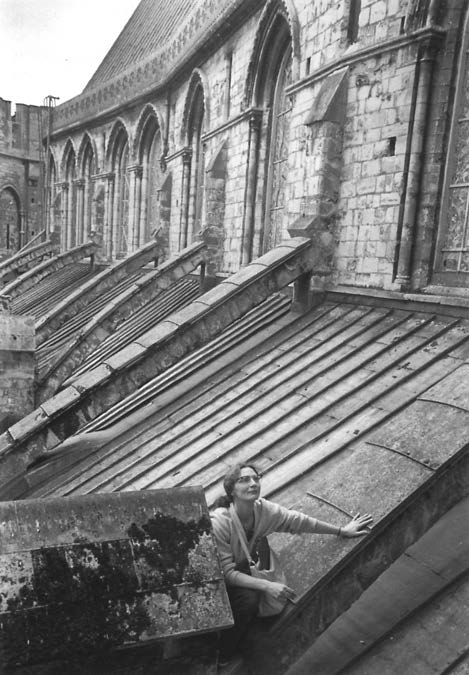

Kathleen Biddick: Many “feminist” undergraduates have appropriated “girl” culture for themselves. When I look at the marvelous frontispiece photograph to Paintings of Glass (it is of you on a side-aisle roof (is it Canterbury Cathedral?) taken in 1970 by Verne S. Caviness) I see an intrepid 32 year old woman, but I also see a tom-boy flickering there as well. Would you comment on aspects of your girlhood that might haunt that 1970 photograph?

Madeline Caviness: That was 50 feet up without a parapet. Grew up a tom boy, wearing my older brother’s out-grown clothes (I WWII) and following him up trees etc. I was nearly expelled from a convent school at about 5 for firing a catapult…the glazier who helped me on the project, George Easton, a poor boy from Canterbury, began to work at 16 and used to slide down the upper roof on the seat of his pants to get to the other side.

Topic: Salvaging Objects, Synthesizing Objects, Transforming the Object Itself

KB: Your work has always struck me as a dynamic triangulation of salvaging, synthesizing, transforming. When I first read Jeannette Winterson’s novel, Sexing the Cherry (1991), these words leapt out at me and reminded me of you. Winterson sets the novel during Cromwell’s civil war. Does this passage have any resonance for you, or is it too corny?

I went to a church not far from the gardens. A country church famed for its altar window where our Lord stood feeding the five thousand. Black Tom Fairfax, with nothing better to do, had set up his cannon outside the window and given the order to fire. There was no window when I got there and the men had ridden away.

There was a group of women gathered round the remains of the glass which coloured the floor brighter than any carpet of flowers in a parterre. They were women who had cleaned the window, polishing the slippery fish our Lords had blessed in his outstretched hands, scraping away the candle smoke from the feet of the Apostles. They loved the window. Without speaking, and in common purpose, the women began to gather the pieces of the window in their baskets. They gathered the broken bread, and the two fishes, and the astonished faces of the hungry, until their baskets overflowed as the baskets of the disciples had overflowed in their original miracle. They gathered every piece, and they told me, with hands that bled, that they would rebuild the window in a secret place. At evening, their work done, they filed into the little church to pray, and I, not daring to follow, watched them through the hole where the window had been.

They kneeled in a line by the altar, and on the flag floor behind them, invisible to them, I saw the patchwork colours of the window, red and yellow and blue. The colours sank into the stone and covered the backs of the women, who looked as though they were wearing harlequin coats. The church danced in light. I left them and walked home, my head full of things that cannot be destroyed.[1]

MC: Yes, so much….though I never say “our Lord” (I became atheist at about 4 years old. The bombing had an enormous effect on me-my brother and I went out one morning to find when the close bomb had dropped the night before, and collected shrapnel from a crater near a friend’s house. We saw London burning from our upstairs windows, 30 miles away in Chesham Bois, Bucks. I love people, but that is always tinged by knowing they have to die. I have worked very hard to ensure that medieval stained glass will not “die”. And I have spent hours trying to match scattered fragments, trying to get them back together…I am very upset now at what they are doing in Iraq, to people and cultural treasures.

Count(er)ing Generations

KB: There has been much talk in feminist literature lately about ways of thinking about “generations.” I love especially the following essay: Elizabeth Freeman, “Packing History, Count(er)ing Generations,” in New Literary History.[2]

She writes that the language of “feminist waves” and “generations” sometimes effaces: “the mutually disruptive energy of moments that are not yet past and yet are not entirely present either” 742. As you think of your published scholarship, the students you have trained, how do you describe the temporal relations of your own feminism?

MC: My answer is probably oblique because I don’t know the essay…I think I was always a feminist without knowing it, and one sign is that women students flocked to my classes and young men were always more uncertain of me. But I had a very uneasy relationship with girls growing up—all girls’ schools can be pretty vicious places. At the moment I do feel caught up somehow in what is often regarded as old “complaining feminism” (so how come women are not supposed to complain anymore if they are still not treated fairly?) and caught between the theory that I understand that questioned whether there is some entity called “women” and praxis that tells me women are the ones being prevented from getting birth-control counseling or abortions. And I tell students that the oppressor is also always oppressed….the construction of gender is a kind of social control.

What is in a Medal?

KB: I am always touched by the intrepid way in which your wear your Haskins Medal at official scholarly meetings. Few women have won that award since its inception in 1940: Bertha H. Putnam (1940); Pearl Kibre (1964); Madeline Caviness (1993); Marcia Colish (1998); Mary Carruthers (2003). Would you comment on the engendering of the Medieval Academy over the time you have been associated with it. What is in the medal for you?

MC: Well yes I think it was an important medal for women when I won it. And I am amused to wear it because as a woman I can and the men can’t or don’t. But it is also a talisman, especially since my feminist work has sat so badly with some of the very same people who I know respect the medal—so it’s in their face. It has always puzzled me that my books won prizes (the first book was awarded the John Nicholas Brown prize, and last year I received the AAUW Educational Foundation senior scholar award, along with Madelyn Albright who got the service award)—yet I have given up applying for research fellowships. I have not had a funded sabbatical since 1986-87.

KB: What projects (of any description, not to be limited to scholarship) are you anticipating after your retirement?

MC: I am afraid too many—I feel completely disorganized, and I confuse the past and the future (I think about scuba-diving again and jogging in the woods and I probably can’t do either; or training a horse again, which I might, but have not since I was 20). I look forward to time with my daughters and their children, and hope to be flexible so I can help out if careers and child-care collide. I have two books to finish, and feel some pressure—the Sachsenspiegel with my colleague Charlie Nelson, and my last debt to stained glass—the Corpus volume for New England. Less pleasant, we have to move from our 5 story town-house and consolidate all my files and books…And I have to walk the streets again for the next election.

I still addicted to travel, and love going to the annual assembly of the Union Académique Internationale, and serving on the boards of GERM and the editorial board of Diogène. I’d like to go back to China, and Bénin…

What’s in a Motto?

KC: If each Haskins Medal recipient was responsible for inscribing their own motto on their medal, what would you inscribe?

MC: That’s really hard because I never feel tied down. When I was turned down for early Tenure at Tufts (I was already chairing the department) I typed on a piece of British Government toilet paper one of those sayings of the 60s: Commitment is to prisons and mental institutions. Odd, because, I have been very committed. My school’s motto was festina lente. I used to laugh at it (so genteel). But it’s not so bad. I have done that: hasten slowly.

Where is the “NOW” in Medieval Studies?

KB: If you were graduating from college now, where do you think your heart and mind would lead you?

MC: Twenty years ago I wished I could start over in law school and be more effective in working against discrimination. I had any way wanted a career in government…more recently I think I have been very lucky to have a kind of career in international diplomacy that came about mainly because I am a good scholar, and also because I like helping collaborative projects along. I realized I was much more free to negotiate than an old English friend who was at the UN. Now I can imagine medieval studies as an avocation…though…I have recently neglected to teach students sufficiently about the material aspects of visual works because I have been more preoccupied with theoretical issues….but I don’t think “art historians” can stay away from that for long. But I worry that only wealthy white people go into the field; and that I can discuss Rauschenberg with a modernist critic, but few if any contemporary artists or critics would think the Middle Ages interesting.

Kathleen Biddick is a Professor of History at Temple University. Biddick’s interests are in critical historiography, especially discussions of temporality, cultural studies of technology, gender studies and medieval history. Her most recent monograph, The Typological Imaginary: Circumcision, History, Technology extends her critical work on temporality and periodization.

Madeline H. Caviness is Mary Richardson Professor at Tufts University and a former President of the International Academic Union and the International Council for Philosophy and the Humanistic Sciences. Author of many books and articles on medieval art, she has recently published Visualizing Women in the Middle Ages: Sight, Spectacle and Scopic Economy. Her recent publications ‘triangulate’ medieval works with historical context and postmodern theories, examining the tensions between the two approaches. She has served as Visiting Professor at Williams College and at the Institute of Fine Arts of New York University.

References

| ↑1 | Jeanette Winterson, Sexing the Cherry, (New York: Vintage Books, 1991), 66. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Elizabeth Freeman, “Packing History, Count(er)ing Generations,” New Literary History 31 (2000): 727-744. https://doi.org/10.1353/nlh.2000.0046 |