Virginia Raguin • College of the Holy Cross

Recommended citation: Virginia Raguin, “Windows on the Working Class,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 10 (2023). https://doi.org/10.61302/JCQM9889.

In the early modern era, medieval materials of stained glass were adopted by the “working class” whose labor had made them prosperous enough to donate a small panel for insertion into the lattice windows of an inn, town hall, parlor, or church. These people for the most part, had not inherited their wealth, but were a part of the local citizenry who had prospered from changing political and social structures and were eager to demonstrate their loyalty to civic and religious organizations. Measuring about fourteen by ten inches, and popular in Switzerland and southern Germany, the panels celebrated marriage alliances, trade guilds, and professions. Switzerland’s initiation of a democratic form of government was among the earliest in Europe. The original Swiss Confederation numbered Eight Cantons, who gained their independence between 1291 and 1353. After the Swabian War of 1499 when the Confederacy defeated the forces of the House of Hapsburg, the nation was essentially sovereign. The need for self-sufficiency for so much of the population across a mountainous landscape encouraged cooperative enterprises. In many smaller towns, the glass painter also worked at other occupations, such as innkeeper. Members of town councils and law courts exercised these positions periodically, most having other trades. Among the working class, I am including teachers. The small panels were given as testimonials of solidarity and friendship and were produced in large numbers.[1]

While in other areas a coat of arms was associated with nobility, Switzerland’s political history allowed most citizens to have their own coat of arms regardless of class. Many of these “badges” proclaimed the trade of the individual, a farmer’s plowshare, a vintner’s pruning knife, a tailor’s pair of shears, or a baker’s pretzel. Anna Russakoff, in this volume, has also noted the adoption of coats of arms for corporations in fifteenth-century Paris. Quite frequently a housemark was chosen (marc de maison, Hausmarke). They were abstract signs, designed to be easily cut or engraved with a knife on livestock, property, or buildings. They appeared in shields of farmers, tradesmen, merchants, artisans, and other town burghers. We also find coats of arms constructed by reference to the family name (canting arms), exemplified by the shields of the Colmar goldsmith Ludwig Hanelutz and his spouse Elizabeth Kölbin, discussed below.

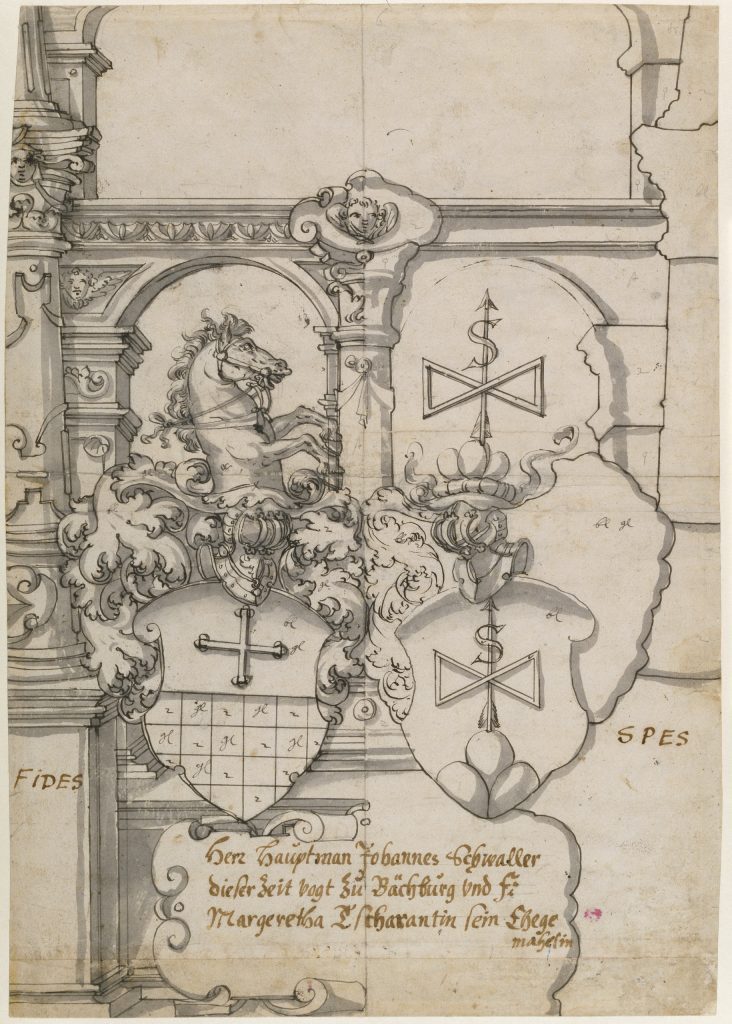

An explanation of the method of construction will facilitate an understanding of the technique of glazing, especially for these small panels made for the prosperous working class. They were not the monumental medieval windows that one associates with sites such as the cathedral at Chartres or the Sainte-Chapelle of Paris and their noble donors. Post-medieval agreements between the commissioner and studio have been preserved in sketches known as a vidimus, Latin for “we have seen.”[2] A late sixteenth-century pen and ink drawing for a window by Hans Jacob Plepp (Fig.1), for example, contains only a portion of the design; there is no need to repeat drawings of elaborate architectural decoration for the client once an exemplar is produced.

Fig 1. Hans Jacob Plepp, Stained-Glass Design with Two Coats of Arms (recto), c. 1590 – 1595. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 91.GG.69.

In the inscription panel, we read the agreed-upon text, Herr Hauptman Johannes Schwaller dieser zeit vogt zu Bächburg und F. Margeretha Tscharantin sein Ehege mahlin (Captain Johannes Schwaller, current governor of Bächburg and Margeretha Tscharantin, his wife).[3] Bechburg is in the canton of Solothurn, in the northwest of Switzerland. We do not see the calligraphy as it will be rendered in the cartouche. The allegorical virtues are named, not drawn; Fides (Faith) and Spes (Hope). Arguably, the client had been shown drawings of these stock figures in the glass painter’s studio for approval. The sketch is a reasonable size for Swiss panels of this time, 16 11/16 x 11 5/8 inches, so we may presume that it is a one-to-one-ratio.

Once there is an agreement, the workshop fabricates the panel. Sheets of glass are split into the required sizes for the segments in the panel. In this era, artisans used a hot iron to score the glass after which cold water would initiate a break. Multiple breaks, followed by a process called grozing, nibbling at the sides, results in the required-size pieces. The pieces are then painted with a low-firing, essentially clear, glass-flux and opaque metallic oxides, generally iron or copper. This is mixed with a clear binder and then applied with a brush in a wide range of painting styles. Enamel was a technique that grew in popularity in the seventeenth century. Intensely-colored ground-up glass suspended in a liquid medium is painted onto the base glass and fused onto its surface. Enamels became a staple for later Swiss production, less expensive, and enabling more detail in a smaller area and almost entirely displacing the use of pot-metal glass (glass colored in its mass while in the molten state).[4] After the segments of glass are painted, they are fired in a kiln to approximately 1250° F. As the glass-flux softens and the surface of the glass sheet becomes tacky, they fuse to create a permanent bond. The segments are then set into lead cames which can easily bend around the glass, soldered at the joints, and set into a frame.

These small panels, serving a society that rarely installed monumental art, were of distinct types. This essay attempts to give a broad overview, endeavoring to survey different categories of donors and the variety of work honored. They include husband and wife, the couple with their children, brothers, guilds, law courts, and associations of colleagues. The so-called “welcome” panel, a variant of the alliance panel such as that of Schwaller and Tscharantin, mentioned above, was a long-lived format. Husband and wife occupy the central scene, sometimes accompanied by their children. We see here the continuation of gender hierarchy, the male on the dexter (viewers’ left) and female on the sinister (viewer’s right).[5] Often, the wife holds a beaker for the husband, and he is dressed in parade armor or citizen’s dress while holding a halberd or a banner. The man can also appear mounted. Above the couple are scenes of agriculture or commerce, such as plowing with a team of horses or oxen, the transport of goods, fishing, or the production of honey. In the 1634 Welcome Panel of Daubenberger and Gerber, citizens of the town of Eichstätt in southern Germany, for example (Fig. 2), husband and wife are each framed by an arch that is supported by a central pillar.[6]

Fig 2. Lingg workshop, Alsace, attributed, Panel of Hans Jerg Daubenberger von Eychstett and Anna Gerber, 1634. Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

The husband’s shield shows a housemark as well as a meat cleaver and a dove perched on a green triple mount, a play on the husband’s name, Dauben, for Taube, meaning dove. The wife’s family arms are suppressed, although her family name is recorded. Above, a scene of driving cattle provides a counterbalancing horizontal to the inscription panel below. Both the arms, and the image of cattle suggest that Daubenberger was a butcher or a dealer in cattle. The placement of these horizontal vignettes of daily life is indebted to the long tradition of the labors of the months prevalent in calendar pages of Books of Hours. We can refer to examples such as the Slaughtering of an Ox and Grape Harvesting for October from the early sixteenth-century Spinola Hours from the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.[7] Hans Jerg Daubenberger emphasizes his importance not only by being portrayed as elegantly dressed and mounted on a white horse, but also by his reappearance above, supervising a laborer who drives cattle, presumably to market. The laborer is dressed in a far simpler doublet and wears leggings and shoes rather than boots. Still, we recognize the ethos of the era that wished to proclaim the value of work and a hands-on presence.

Often the Swiss panels display both coats of arms below the couple, with the same sinister/dexter hierarchy. The shields stand either between the couple or at their feet. Exemplifying this convention, is a Stained Glass Design for a Married Couple in the J. Paul Getty Museum (Fig. 3).[8] The inscription reads “Bicius Haller und Barbly Fluomanin (Flühmann) sin Hussfrouw.” The arms are those of the Bern statesman Sulpitius Haller (c. 1525–1564) and his wife Barbara Flühmann. The crested helms of the nobility are gone and in their place are beehives, symbols of domestic industry. The male supporter stares at the female who demurely casts her eyes downward. He carries a flail used in threshing to separate grains from their husks. The female holds a distaff, wound with wool or flax for spinning. Both emblems were long associated with gendered divisions of labor, the male with the outdoor labor of farming and the female with the home-bound production of textiles.

Fig 3. Unidentified artist of Bern, Stained Glass Design for a Married Couple (Sulpitius Haller and Barbara Flühmann of Bern), 1553. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 89.GG.18.

A marriage panel of Hans Ludwig Hanelutz and Elizabeth Kölbin (Fig. 4) shows both husband and wife as well as their arms, but focuses on the husband’s labor as a goldsmith.[9] Above their portraits is a scene of monkeys at work in the shop, blowing on a fire with bellows and hammering, drilling, and embossing metallic objects (Fig. 5). The specificity of their labors recalls the depiction of diverse building trades in mosaics from the Eastern Mediterranean, discussed by Hallie Meredith in this volume. Hans holds a hammer in his right hand just as does the demi-man surmounting the helm. On the right, Elizabeth holds a beaker in her outstretched hand, in a gesture of service. At her feet a boy, possibly their son, plays with a pan and spoon. A dog watches. The canting arms shows the device on the shield as a visual pun on the name of the family. For Hanelutz, the cockerel is associated with Hahn (cock), and lütt or lüttje dialect for small), hence, little cock, or cockerel. The wife’s last name of Kölbin can be pronounced Kolben, which means mace or club, as seen in the coat of arms. An inscription in the scene, to the right of the demi-man in the helm, reads “ach got biss du unss/ bauer drost./ Du hast unss[ . . . ] erlosst (Oh God you are the consolation of us both, for you have saved us). A shield with the husband’s arms appears in the center of the inscription panel whose text identifies him as a goldsmith: Hans Ludwig Hanelutz, citizen and goldsmith of Colmar and Elizabeth Kölbin of Nuremberg his wedded wife, the year 1582. Horst W. Janson specifically mentions the Hanelutz and Kölbin panel in his study of apes and ape lore, describing the scene as “innocent merriment” and suggesting that the panel would have been made for display in the local Zunfthaus (guildhall) of the local goldsmith’s guild.[10]

Fig 4. Germany, associated with a workshop from Zug, Switzerland, Heraldic Panel with the Arms of Hanelutz and Kölbin, 1582. William Randolph Hearst Collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 45.21.41.

Fig 5. Detail, monkeys in the goldsmith workshop from Arms of Hanelutz and Kölbin.

The imagery relates to the late–medieval transformation of the ape into a commentary on human behavior. Other animals were also depicted. A Swiss panel of the early sixteenth century shows the arms of three men surrounded by a wide border containing bears in various stages of making wine.[11] Many printed Books of Hours depicted an astrological image of “planetary man” integrated with the Four Humors. In an example dated 1534, the sanguine humor is personified by a well-dressed young man carrying a hawk and accompanied by a monkey (Fig. 6).[12] The choleric humor has a lion, the melancholic a ram, and the phlegmatic a pig.[13] Around 1562, the Antwerp engraver Pieter van der Borcht, produced an album of eighteen prints where monkeys parody human activities including hunting, experimenting with alchemy, practicing the trade of a barber, cooking (Fig. 7), doing laundry, or at home, engaged with caring for children and other domestic duties.[14] The donor commissioned the image and determined the subject matter. Although satiric, the monkeys certainly were not intended to demean Hanelutz’s own labor. France would continue this tradition into the eighteenth century with wallpaper, porcelain, and paintings of singerie.[15]

Fig 6. Jean Pichore, Planetary Man, on right, detail of Sanguine Temperament, from a Book of Hours, Paris, 1534. Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia.

Fig 7. Pieter van der Borcht, after Pieter Bruegel and Pieter van der Heyden, Lean Kitchen, from the series Monkey Games, possibly Amsterdam, 1563 – 1608. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, RP-P-1891-A-16317.

Family ties are exemplified by a Swiss panel showing a Farmer with his Wife and their Four Daughters (Fig. 8).[16] As the scene has lost its lower inscription, the precise name and date is unknown. The farmer is prominently set to dexter, holding a pike in his left hand and resting his right hand on his dolch, the characteristic Swiss knife at his waist. Facing him, his wife presents a silver cup trimmed in gold. Behind her are their four daughters. The stance and dress of the women are almost identical, reiterating the gendered conventions of the time, but vary in color. They wear white coifs and ruffs at neck and wrist, over dresses with tight-fitting bodices and puffy sleeves at the shoulders. The long skirts are split in the front to display petticoats. Those of the daughters are white, while the wife’s is a deep purple that corresponds to her bodice. The wife and her oldest daughter both wear wimples. From each of the daughter’s belts hangs a pouch with a scabbard containing eating utensils such as a small knife and fork; that of the wife, however, shows keys, demonstrating her responsibility for the household. Supported by the simple architectural frame, activities of a prosperous farm appear above. On the left is a scene of plowing with a team of oxen, on the right, one with horses. In the scene of the horses, we may be seeing the owner holding a whip, as he is dressed in bloomers and wears a hat with a feather. His wealth is demonstrated by his having employees and teams of six animals to draw each plow. However, he is actively a part of the labor as he guides the horses who pull the plow and echoes the position of the man guiding the team of oxen.

Fig. 8. Switzerland, Aargau (?), A Farmer with his Wife and their Four Daughters, 1600-1610. William Randolph Hearst Collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 45.21.31.

Similar to these representations of couples, many panels appear to illustrate what a modern viewer might call “family values.” A panel of two brothers (Fig. 9) is inscribed Caspar Laser und/ Hans Laser gebrūd/ er zū Lüpfertschwÿll/ Anō 1647 (Caspar Laser and Hans Laser, brothers of Lüpfertschwil [now known as Lüpfertwil] the Year 1647).[17] Below them are their arms, on the left azure, a fleur-de-lis or (Caspar Laser); and on the right, or, in base an Imperial eagle sable armed and beaked or in chief the initials H L sable (Hans Laser). They show pride of citizenship standing in the center of the panel; they carry muskets in one hand and wear baldrics over their shoulders with powder charges attached. In their other hand are musket rests (also called musket forks); Hans, the brother on the right, also holds a glowing match with which he will light the musket. They are not professional soldiers, however, but citizens of a hamlet of the local community Ebnat-Kappel, in the present electoral district of Toggenburg in eastern Switzerland.[18] They were farmers, relying on each other for support, as they demonstrate through the imagery. They also demonstrate the “work” required of all male citizens, their readiness for defense. When called, they would contribute their skills in using their weapons in service to their region. To this day Switzerland keeps a militia system stipulating that the members keep their own personal equipment, including weapons, at the ready.

Fig 9. Abraham Wirth, Lichtensteig, attributed, Heraldic Panel with the Arms of the Brothers Caspar and Hans Laser, 1647, William Randolph Hearst Collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 45.21.50.

Above the two brothers is a scene from one of Aesop’s fables (Fig. 10), a tale reputedly set in Greece during the sixth century BCE. The Old Man and his Sons, also called The Bundle of Sticks, was retold in Roman times, with the identification of the man as Scilurus, a king of Scythia in the second century BCE. The latter text was associated with the Roman historian Plutarch, early second century CE: “Scilurus, who left eighty sons surviving him, when he was at the point of death handed a bundle of javelins to each son in turn and bade him break it. After they had all given up, he took out the javelins one by one and easily broke them all, thereby teaching the young men that, if they stood together, they would continue strong, but that they would be weak if they fell out and quarreled.”[19]

Fig 10. detail, Scilurus and his Quarrelsome Sons, from Heraldic Panel with the Arms of the Brothers Caspar and Hans Laser.

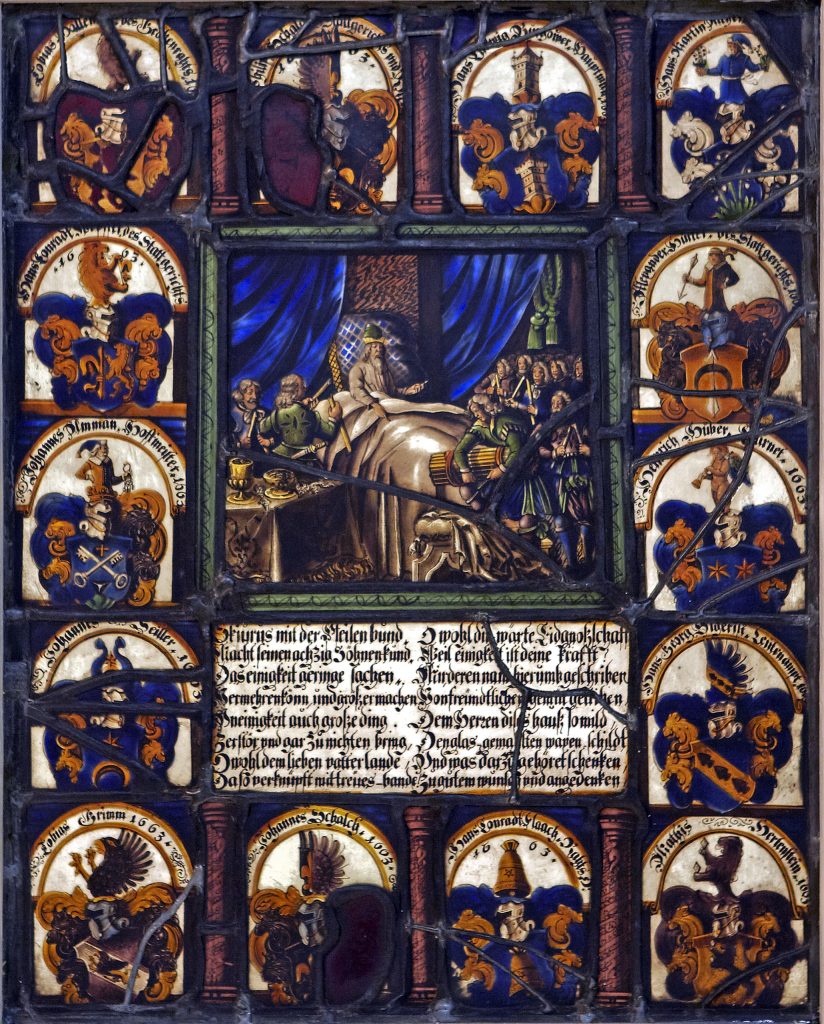

The moral of strength in unity is appropriate for a panel depicting two brothers in the militia. It was a popular citation, however, as it had particular relevance to the Swiss Confederation. The fable appears during the same decade, in a panel dated 1663, from Schaffhausen, now in Princeton University Art Museum.[20] Given by Schaffhausen’s Bürgermeister (mayor), Leonhard Meyer, it advocated unity for the ruling council of the city (Fig. 11). The story of the dying man is placed in the center and surrounded by the arms of the council members. The long text includes the admonitions: “Unity can increase and make greater, lesser things/ Disunty (can) also destroy greater things . . . Health to the awaited fraternity/ because unity is your strength.” Earlier, Tobias Stimmer had executed a powerful design focusing on the father’s deathbed.[21] A panel, dated 1607, by Werner Kübler the Younger of Schaffhausen shows a similar arrangement of the parable in its central scene.[22]

Fig 11. Hans Heinrich Ammann, Schaffhausen, attributed, Aesop’s Fable of the Bound Sticks and a Man’s Quarrelsome Sons Surrounded by Heraldic Panels, 1663. Princeton University, The Art Museum, New Jersey, 61-52.

The same themes of loyalty and co-dependence and also hierarchy of gender and class are vividly demonstrated by imagery commissioned by trade guilds.[23] In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the guild panel (Zunftscheibe) had as much diversity in form as other association panels (Gesellschaftsscheibe) particularly in Basel, Zurich, and Winterthur where guilds were traditionally strong.[24] In these representations, the members are recognized primarily by their inscribed names and arms, which usually surround the main scene and correspond in number to the figures assembled.

One of the most famous examples is Hieronymus Vischer’s Banquet of the Basel Ropemakers Guild of 1615 (Fig. 12).[25] Fourteen men sit at the table with their shields and names arranged on the lowest tier. Again, we see the exclusion of women from the trades. The segment at the top of the panel shows the guild members producing rope, from the beating of the hemp to the twisting of the rope. The larger panel below shows the members enjoying the fruits of their labors, the leisure to meet for a festive banquet in a guild hall or inn. The banquet hall is characterized by rows of bulls’ eye windows which are regularly interrupted at the top by a small rectangular area in which colorful gift panels of the kind we are studying would have been inserted. At the side, the architectural frames are standard, baroque ornaments, here showing caryatids with female heads supporting baskets of fruit, symbolic of prosperity.

Fig 12. Hieronymus Vischer, Banquet of the Basel Ropemakers Guild, 1615. Historisches Museum, Basel, 1901.42.

The Basel Tailor’s Guild, dated 1554, shows another guild composed of males only. The arms of the members are set above and below the figures and follow the curvature of the table (Fig. 13).[26] Among those administering to the company, dexter and sinister gender depictions prevail. On the right a woman serves food and another comes up the stairs with bread loaves. On the left a man provides drink and another enters carrying a flask marked with a shears. Those serving, male or female, are well dressed. Indeed, the man filling the cup is clothed in similar dress as the members of the guild. Those delivering the food, however, are less elegantly attired. Both male and female servers are included in such a way that does not interrupt, but rather accentuates the group’s well-being and conviviality. The panel seems to indicate a respect for occupations; managing an inn or producing clothes were equally productive contributions to society. Above, in the spandrels, are scenes of crude guild initiations where men are physically humiliated. One is hit on the head with a paddle and another is drilled at the buttocks with a screw.

Fig 13. Tailor’s Guild of Basel, 1554. Historisches Museum, Basel, 1870.1284.

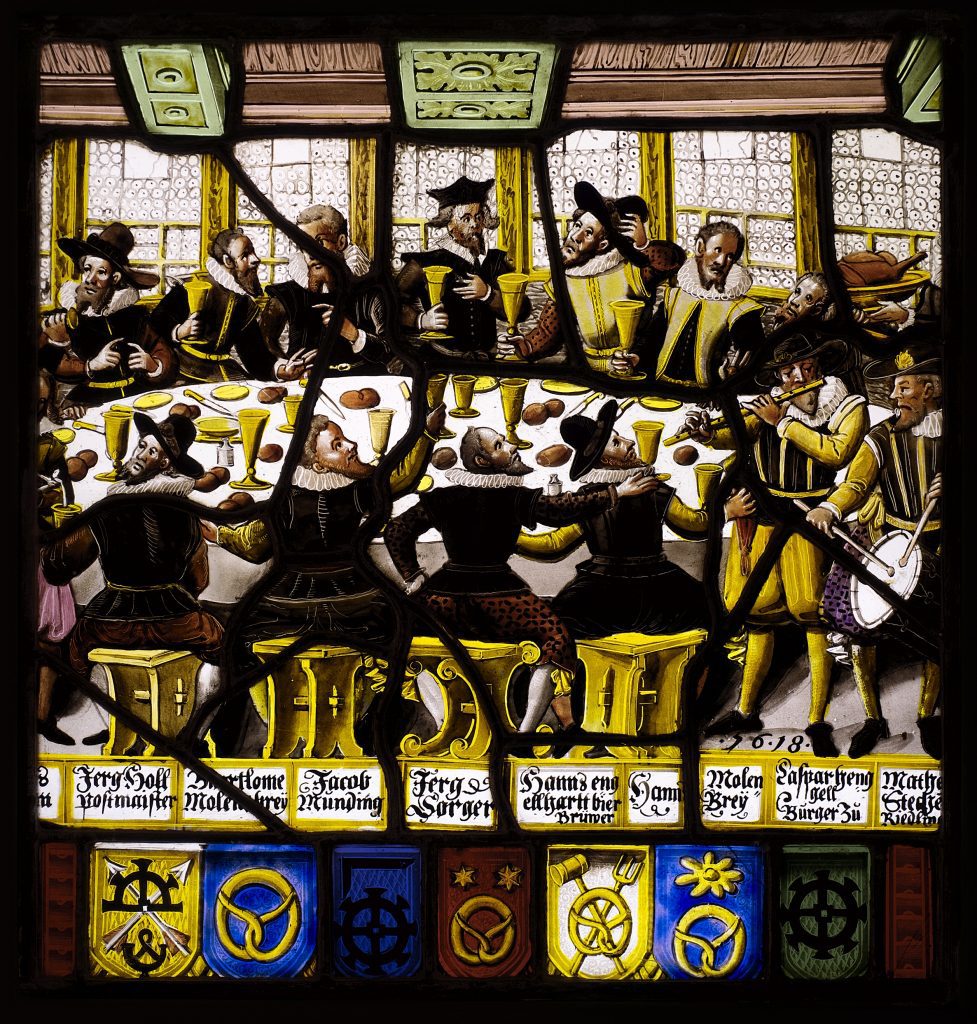

A guild of millers or brewers (Fig. 14) present a similar scene in a room glazed with bulls’ eye windows under a wooden ceiling with heavy cross-beams.[27] A row of inscriptions and coats of arms are below. In this truncated panel, twelve guild members are still visible. They wear black doublets with white ruffled collars. The division of labor seen in the Ropemakers Guild is repeated: food brought by women from the right and drink by men from the left. Bread rolls and tall goblets fill the surface of the table that dominates the room, allowing just enough space for the musicians, playing flute and drum, to stand in their customary place in the right foreground. The most distinguishing trait of these scenes is the variety of animated gestures and mannerisms enacted by the men at table. The viewer’s attention is drawn to the guild master and figure beside him, who removes his hat to pay his respects. It is difficult to ascertain when the portrait of the guild master (Fig. 15) was defaced by scratches but it is tempting to believe that the perpetrator acted with knowledgeable animus towards the individual or his descendants. Defacement also may have been motivated by animus towards someone simply claiming a superior status at the table; the act would have been an effort to efface such claims of hegemony.

Fig 14. Southern Germany, Constance (?), Banquet Scene of a Guild of Bakers or Millers, 1618. William Randolph Hearst Collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 45.21.40.

Fig 15. Detail, defaced and repainted head, Banquet Scene of a Guild of Bakers or Millers.

Law courts commissioned panels such as the Banquet Scene of the Members of the Law Court of Goldach (Fig. 16).[28] Dated 1580, the panel is signed by Niklaus Wirt, from the canton of St. Gallen, eastern Switzerland (the upper section of the table is most probably a later replacement). Although this work’s original placement is unknown, such panels are routinely found in halls of justice (Gerichtssaal). In search for context, we might think some sixty years forward to the prosperous and populous Lowlands of Rembrandt’s Night Watch of 1642. Despite its monumental size, something completely unknown for independent paintings in Swiss artistic traditions, the painting is simply a group portrait of a civic militia commissioned for the Musketeers’ Meeting Hall in Amsterdam; its proper title is The Company of Frans Banning Cocq and Willem van Ruytenburch.[29] The heraldic arms of the company also appear, portrayed through the young woman in the yellow dress with a dead chicken dangling from her belt by its feet, a play on the name Cocq as well as that of the arquebusiers (clauweniers). She even holds a covered beaker in her hands, reiterating the gesture of the female offering a goblet to greet her male counterpart, as in the Welcome Panel of Daubenberger and Gerber, discussed above.

Fig. 16. Niklaus Wirt of Well an der Würm (Weil Der Stadt), St. Gallen, Banquet Scene of the Members of the Law Court of Goldach, 1580. William Randolph Hearst Collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 45.21.17.

Goldach is a town on the Bodensee, close to the German border; the German city of Constance is about thirty-five kilometers to the west. The men’s names and shields, almost all of them employing housemarks, are included in rows at the sides and bottom. The individuals were not full-time or even permanent members of the law court, but rather citizens with other professions who periodically met to render judgments. Like the Dutch participants, the members of the company are given distinctive clothing, a variety of hats, doublets, pantaloons, and sleeves to suggest the normal diversity of a group of individuals. Details in the foreground, such as the dog gnawing a bone beside a bowl of bones and the tin pitcher of beer add humor and naturalness to the event. The dog gnawing on the bone is a frequent feature, as seen above in the scene of the Basel Tailors Guild. Since the glass painter Niklaus Wirt acted biannually as judge of the law court of Wil from 1576 to 1584 and was also an active member of the Wil town council, he probably had a personal or even judicial reason to produce this panel for the Goldach court.[30]

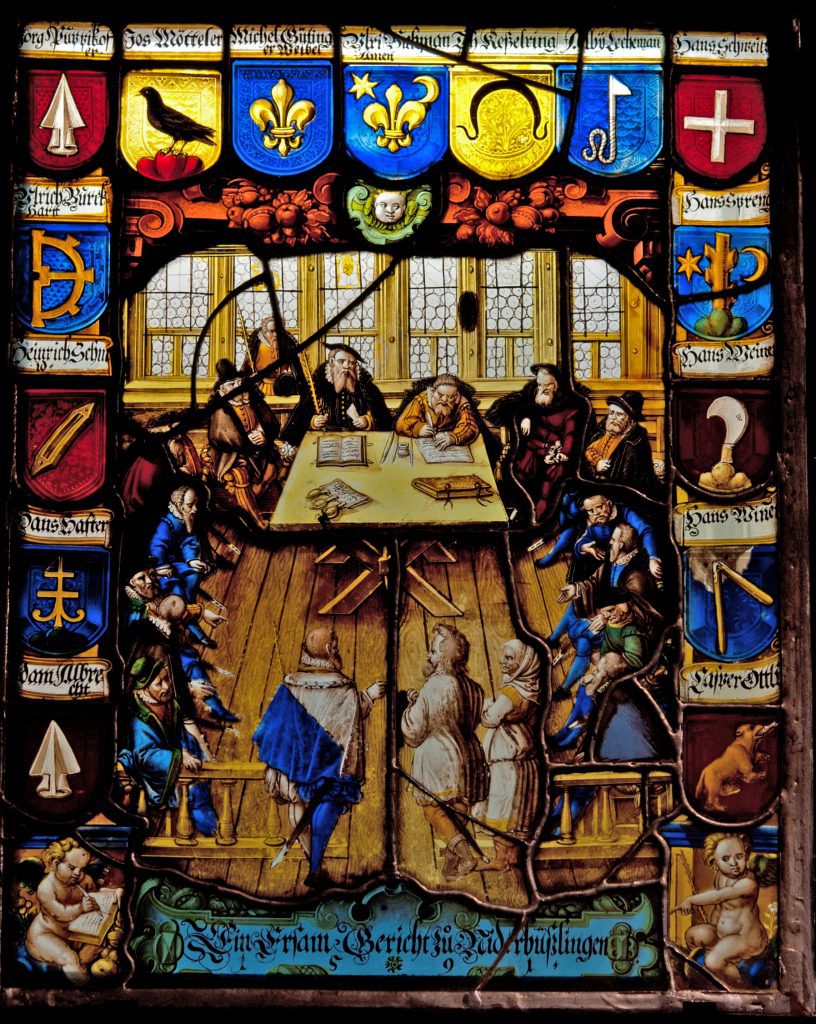

More common is the representation of a court in session, such as the panel of the Law Court of Niederbussnang, dated 1591 (Fig. 17).[31] Niederbussnang’s panel shows several plaintiffs before a table surrounded by fourteen members of the court. At the top and sides of the panel their shields are surmounted by their names. One member keeps notes of the process while another presides. The bird’s eye-perspective of the room, looking down on the proceedings, is like that employed for the Basel Taylors’ Guild.[32] As in the previous examples, the banquet hall is shown with rows of bulls’ eye windows framing rectangular panels. Two putti framing the inscription at the bottom mimic the actions of the court. To the left, one takes notes and, on the right, another holds a staff of authority similar to that clasped by the presider on the left side of the table.

Fig 17. Wolfgang Breny, Law Court of Niederbussnang, 1591. Thurgau History Museum, Frauenfeld.

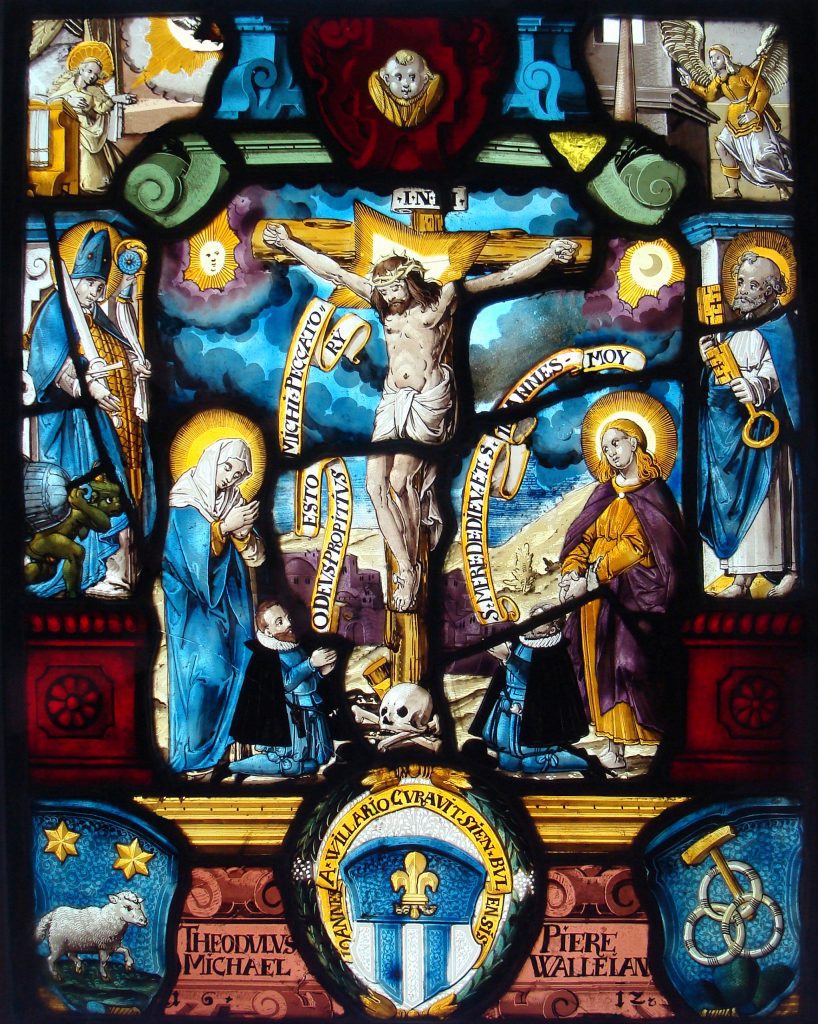

Confessional differences inspired many donors in the design of their panels. This motivation is seen in a panel of the Crucifixion from Fribourg (Fig. 18) with two men meditating at the foot of the cross.[33] Théodule Michel and Pierre Walleian (Vallélian) address the images of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and St. John that they see in their mind’s eye. Their prayers of intersession are uttered both in Latin, the official language of the Catholic Church, and in the French vernacular. The imagery is complex and theological. Danai Thomaidis in this volume, describes an icon of the Three Magi acquired by Antonio Bosio, a scholarly Venetian book-seller. His choice of subject matter, the learned “magi” honored his own profession in furthering the dissemination of wisdom. The Swiss donors, similarly erudite, as discussed below, were keen to stress the multi-lingual and time-honored Catholic tradition in their country recently challenged by reformers. Christ is flanked by images of the sun and moon, references since at least Carolingian times to the darkness that fell during the Crucifixion: “Now from the sixth hour there was darkness over the whole earth, until the ninth hour” (Mathew 27: 45). The darkness is represented here by purple clouds. Here we also see the idea that the celestial bodies stood as witnesses for all of creation, mourning the death of the creator. At the base of the cross is a skull, a double reference that Golgotha “means ‘The Place of the Skull’” (Mark 15:22) and that it was also believed to be located above Adams’s tomb. Adam’s burial directly below the Crucifixion associates Adam, whose actions caused harm to the human race, with Christ, the new Adam (I Corinthians 15), who brought eternal life.

Fig 18. Switzerland, canton of Fribourg, Crucifixion with Heraldic Shields of Michel, Vallélian, and Villard, 1612. William Randolph Hearst Collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art,37: 45.21.40.

Fribourg, in western Switzerland, remained a staunchly Catholic region among the many cantons who adopted the Reformation. The two donors, in small format, are similarly dressed in black cloaks over blue doublets, breeches, and hose. Théodule Michel exercised the profession of notary since 1612 and served as secretary of the bailiff tribunal (curial) of Bulle in 1641 and 1643. He also held the post of banneret (charged with leading soldiers into battle) in 1661. Théodule Michel’s profession is unknown, but he was the father of Georges Michel (1620–after 1677), who was a doctor of theology and priest in Bulle from 1646 to 1677. Théodule died in Bulle on January 30, 1670.[34] A central shield speaks of a Jean du Villard of Bulle, who is not imaged, and who has not been found in archival searches.

At the sides, the donors’ patron saints watch from pedestals. On the left is St. Theodule dressed as a bishop with a blue cope and miter and a yellow chasuble. In one hand he holds a crosier, with a sudarium (veil) hanging from the top (indicating an abbot), and in the other he carries a sword with the blade resting on his shoulder. Theodule was a fourth-century bishop, whose diocese was the oldest in Switzerland; the image shows the power of his successors as secular lords as well as spiritual leaders. Theodule was particularly honored in the area in the southwestern part of Switzerland, including the cantons of Fribourg and Valais which remained Catholic. The region’s conservative position can be associated with its unusual fusion of temporal and ecclesiastic. Valais, for example, was actually ruled by the prince-bishops of Sion, who traced their authority to St. Theodule. At the saint’s feet, a green demon equipped with yellow testicles struggles to carry a blue bell, referring to the legend that the bishop forced a demon to carry the papal gift of a bell across the presently-named Theodul Pass. St. Peter stands on the right, carrying his traditional attribute, the keys. The keys are a reference to Christ’s words to Peter, “And I will give to thee the keys of the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 16:19), which Catholics saw as establishing the authority of the pope.

Clearly all of these panels demonstrate an intense relationship between the artist, the donor, and the destination. They were one-of-a-kind creations, each individualized for the person and place. The donors’ professions, family relationships, and faith were primary subjects. Civic pride, extending beyond service in trade corporations and governments to the display of the readiness of all male citizens to defend their land appears in the stance of the fully armed male donor. Gender division is still evident, certainly as the women do not exercise any trade. The wife, and her arms, however, are frequently commemorated. Standing next to her husband she holds the instruments of household management and is given the honor of active partner.

All of these works were commissioned and approved by the donors, unlike most of the imagery presented in this volume. For example, Deirdre Jackson discusses workers depicted in the Cantigas de Santa Maria commissioned by Alfonso X; Anna Russakoff explores the perspectives of Etienne de Boileau, the provost of Paris, who authored the thirteenth-century Livre des Métiers; Lindsay S. Cook discusses trades imaged in the fourteenth-century Grandes chroniques de France, commissioned by Charles V. We too often fail to attribute traits of humor and irony to classes other than intellectuals. Good humor and a sense of self-deprecation are often present, as in a goldsmith’s decision to depict monkeys exercising his trade. He very well may have selected the unusual depiction with the goal of making his panel memorable among those of his fellow guild members. These panels are not the works of individuals looking at “the other,” but acts of self-determination. In the same light, we can appreciate members of a law court commenting on the exacting job of scribe by including in the frame a chubby putto busily scrawling in a book. These insights into early modern self-imaging and the ties that bind citizens in mutual relationships deserve to be better known.

Acknowledgement

The author is grateful for the suggestions made by several anonymous readers and to the initiatives and the guidance of Diane Wolfthal.

References

| ↑1 | Mylène Ruoss and Barbara Giesicke, “In Honor of Friendship: Function, Meaning, and Iconography in Civic Stained Glass Donations in Switzerland and Southern Germany”, in Barbara Butts and Lee Hendrix, eds, Painting on Light: Drawings and Stained Glass in the Age of Dürer and Holbein [exh. cat., The J. Paul Getty Museum], Los Angeles, 2000, pp. 43-55. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The sixteenth-century glazing of Kings College Chapel, Cambridge provides numerous instances of surviving designs that can be compared with the resulting windows; Hilary Wayment, “The Great Windows of King’s College Chapel and the Meaning of the Word Vidimus,” Proceedings of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society 69 (1979): pp. 365-76; Marks 1993, pp. 217-20, fig. 184. |

| ↑3 | Schwaller was a member of the community, and did not inherit the office. This kind of drawing, called a Schiebenriss, was essentially an agreement. |

| ↑4 | The work of the Swiss Corpus Vitrearum has included extensive technical analyses as well as historical overviews. See Stefan Trümpler et al. Glasmalerei im Kanton Aargau: Einfürung zur Jubiläumspublikation 200 Jahr Kanton Aargau. Lehrmittelverlage des Kantons Argau, 2002. |

| ↑5 | Corine Schleif,” Men to the Right and Women on the Left: (A)Symmetrical Spaces and Gendered Places,” in Virginia Raguin and Sarah Stanbury, eds., Women’s Spaces: Patronage, Place, and Gender in the Medieval Church, Albany, SUNY, 2005, pp. 207-250. |

| ↑6 | Panel of Hans Jerg Daubenberger von Eychstett and Anna Gerber, London, Victoria & Albert Museum, possibly from the Lingg workshop. Alsace, as per communication in 2013 from Rolf Hasler, VitroCentre, Romont Switzerland. |

| ↑7 | Spinola Hours, Workshop of the Master of First Prayer Book of Maximilian, Flemish, Bruges and Ghent, 1510– 520, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Ludwig IX 18 (83.ML.114), fol. 6. |

| ↑8 | Unidentified artist of Bern, 1553, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 89.GG.18. |

| ↑9 | Germany, possibly associated with a workshop from Zug? Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 45.21.41, William Randolph Hearst Collection. |

| ↑10 | Horst W. Janson, Apes and Ape Lore in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, London, 1952 Reprint Nendeln, Liechtenstein, 1976, pp. 190-191. |

| ↑11 | Medallion with the Arms of Leuw, Boruttiner and [.]yler, California Private collection, Stained Glass before 1700 in American Collections: Corpus Vitrearum Checklist IV and Addendum to Checklist III, Timothy B. Husband, Marilyn Beaven and Madeline H. Caviness (Studies in the History of Art, 39), Washington, 1991, pp. 232, 241. |

| ↑12 | Planetary Man, printed in Paris c. 1534 by Germain Hardouyn, containing hand-painted metalcuts by Jean Pichore; Philadelphia, Temple University Libraries. The page shows the upper French texts describing the choleric and sanguine humors exchanged. |

| ↑13 | Janson 1976, pp. 248-50. |

| ↑14 | Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, RP-P-1891-A-16317; Janson 1976, pp. 308-309. |

| ↑15 | Nicole Garnier-Pelle, Anne Forray-Carlier, and Marie-Christine Anselm. The Monkeys of Christophe Huet: Singeries in French Decorative Arts, J. Paul Getty Museum. 2011. |

| ↑16 | Switzerland, probably Aargau, about 1600, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 45.21.31, William Randolph Hearst Collection. |

| ↑17 | Abraham Wirth, Lichtensteig, attributed, 1647, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 45.21.50, William Randolph Hearst Collection. |

| ↑18 | Paul Boesch, Die Toggenburger Scheiben, 75. Neujahrsblatt, Historischen Verein des Kanton St. Gallen, St. Gallen, 1935, p. 94. |

| ↑19 | Plutarch, Moralia, trans. Frank Cole Babbitt, vol. III Sayings of Kings and Commanders, Loeb Classics, Harvard University Press, 1961. p. 27. |

| ↑20 | Attributed to Hans Heinrich Ammann, Princeton University Art Museum, 61-52: Virginia Raguin in Stained Glass before 1700 in American Collections: Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern Seaboard States. Corpus Vitrearum Checklist II, ed. and intro. Madeline H. Caviness and Jane Hayward (Studies in the History of Art, 23), Washington, 1987, p. 86; Ibid., Glory in Glass: Stained Glass in the United States: Origin, Variety and Preservation [exh. cat. The Gallery at the American Bible Society], New York, 1998, pp. 57-58, 63-65, fig. VII.4; Rolf Hasler, Die Schaffhauser Glasmalerei des 16. bis 18 Jahrhunderts (Corpus Vitrearum Reihe Neuzeit, vol. 5), Bern, 2010, p. 71, fig. 41. |

| ↑21 | Christian Geelhaar, ed., Tobias Stimmer, 1539-1584: Spätrenaissance am Oberrhein [exh. cat., Kunstmuseum Basel] Basel, l984, pp. 416-18, no. 259, fig. 267. |

| ↑22 | Hasler 2010, p. 251, no. 61. |

| ↑23 | Hermann Meyer, Die Schweizerische Sitte der Fenster und Wappenschenkung von 15. bis 17. Jahrhundert, Frauenfeld, 1884. |

| ↑24 | Paul Boesch, Die schweizer Glasmalerei, Basel, 1955, pp. 110-112, figs. 48-52.and https://vitrosearch.ch/en/search?q=type:Gesellschaftsscheibe. |

| ↑25 | Basel, Historisches Museum 1901.42: Hans Dürst, Vitraux anciens en Suisse /Alte Glasmalerei der Schweiz, Einsiedeln, 1971, p. 127, no. 59; Paul Ganz, Die basler Glasmaler der Spatrenaissance und der Barockzeit, Basel/Stuttgart, 1966, p. 110, pl. 13. |

| ↑26 | Basel, Historisches Museum, 1870.1284; Ganz 1966, p. 19, pl. 2. |

| ↑27 | Southern Germany, Constance (?) Banquet Scene of a Guild of Bakers or Millers, 1618, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 45.21.40, William Randolph Hearst Collection. The panel has been cut off on both sides and the architectural frame around the main scene is missing. There has been rearrangement and replacement of the arms which do not correspond to the number of inscriptions or guild members present. A second row of arms, to correspond with the twelve guild members depicted (which would have appeared above the scene or below the first row), is missing. |

| ↑28 | Niklaus Wirt of Well an der Würm (Weil Der Stadt), St. Gallen, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 45.21.17, William Randolph Hearst Collection. The panel is heavily restored, but the lower sections are original. |

| ↑29 | Egbert Haverkamp Begemann, Rembrandt: “The Nightwatch,” Princeton, 1982; Harry Berger, Manhood, Marriage, and Mischief: Rembrandt’s Night Watch and other Dutch Group Portraits, New York, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1353/book.119896 |

| ↑30 | Schweizerischen Künstler-Lexikon, vol. 3, p. 510; Jenny Schneider, Glasgemälde: Katalog der Sammlung des Schweizerischen Landesmuseums, Zürich, 2 vols., Stafa, 1971, p. 491. https://vitrosearch.ch/en/artists/2653702. |

| ↑31 | Wolfgang Breny, Thurgau History Museum, Frauenfeld; Boesch 1955, p. 104, fig. 44. https://vitrosearch.ch/de/objects/2656979 by Sarah Keller and Rolf Hasler. |

| ↑32 | The panel can also be compared with the depiction of the Municipality of Stammheim in 1635 by the Zurich painter Hans Jacob Nüscheler II. Gemeinde Stammheim: Boesch 1955, p. 97, fig. 40. |

| ↑33 | Switzerland, canton of Fribourg, Crucifixion with Heraldic Shields of Michel, Vallélian and Villard, 1612. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 37: 45.21.40, William Randolph Hearst Collection. |

| ↑34 | According to information provided in 2020 to the author by Leonardo Broillet, archivist of Fribourg, he had at least two other sons, recorded as Jacques and Pierre. Pierre Walleian, (Vallélian) may have been of the same family as Loys Vallélian, a painter, coming from Gruyère, most probably the village of Pâquier. The name must have originated with an individual name Valérien of Pasquier. His descendants took the given name as a family name, which evolved from Valérien to Valérian and then Vallélian. David Bourceroud, “Itinéraire de Loys Vallélian,” Annales fribougeoises 6, 2006, pp. 121–30. |