Ellen Shortell • Massachusetts College of Art and Design

Recommended citation: Ellen Shortell, “Blessed Oda’s (Un)severed Nose: Viewing Self-Disfigurement in Stained Glass from Park Abbey,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 8 (2022). https://doi.org/10.61302/RRDM5291.

In 1986, while examining a group of seventeenth-century Flemish stained and painted glass panels dispersed from the cloister of Park Abbey, I encountered a depiction of a young, haloed nun, about half life-size, with blood running around her nose, down her face, and into a basin. A short, bloodied sword is balanced on the basin’s rim (Fig. 1). Despite the evident trauma, the woman remains impassive, her eyes averted as if deep in thought, the loveliness of her face still showing through the blood. Indeed, there is no wound to mar her face; without knowing the story, the viewer is left to speculate about the source of the blood. The image aroused an old discomfort, recalling the darker side of the Catholicism of my childhood, an overbearing monsignor standing before the crucifix, filling the Sunday School children with terror and shame as he told stories of sin and punishment. At the same time, the figure elicited my sympathy. I was simultaneously repelled and intrigued.

Figure 1. Jean de Caumont, Blessed Oda of Rivreulle, detail, stained glass from Park Abbey, Leuven, c. 1638. Photo: Author.

I would soon learn that the subject was a young twelfth-century noblewoman, Oda of Rivreulle, who cut off her own nose to avoid an arranged marriage, preserve her virginity, and join the Premonstratensian order–a story rooted in ideas about women and sexuality that failed to dispel the shadows of my early religious education. I pushed aside my personal reactions, however, in favor of an “objective” art-historical study of the original conditions of the window’s creation and its monastic context. In fact, knowing that the image was meant for a cloister, I also felt some annoyance at the careless appropriation by modern collectors that had led to its incoherent installation in a room at the Corcoran Gallery of Art that had been closed to the public for many years. At the time, I thought that this “afterlife” was as irrelevant as my memories of Monsignor Fitzgibbons’ lectures. Removed from its original setting and audience, the image was a fragmentary document of a past that felt safely distant. If that were true, however, I would not be writing about it now. Georges Didi-Huberman has described our encounters with historical works of art as an experience of “ghosts that stick to our skin;” this seems a particularly apt description of the effect Oda has exerted on me as I have returned to her again and again.[1]

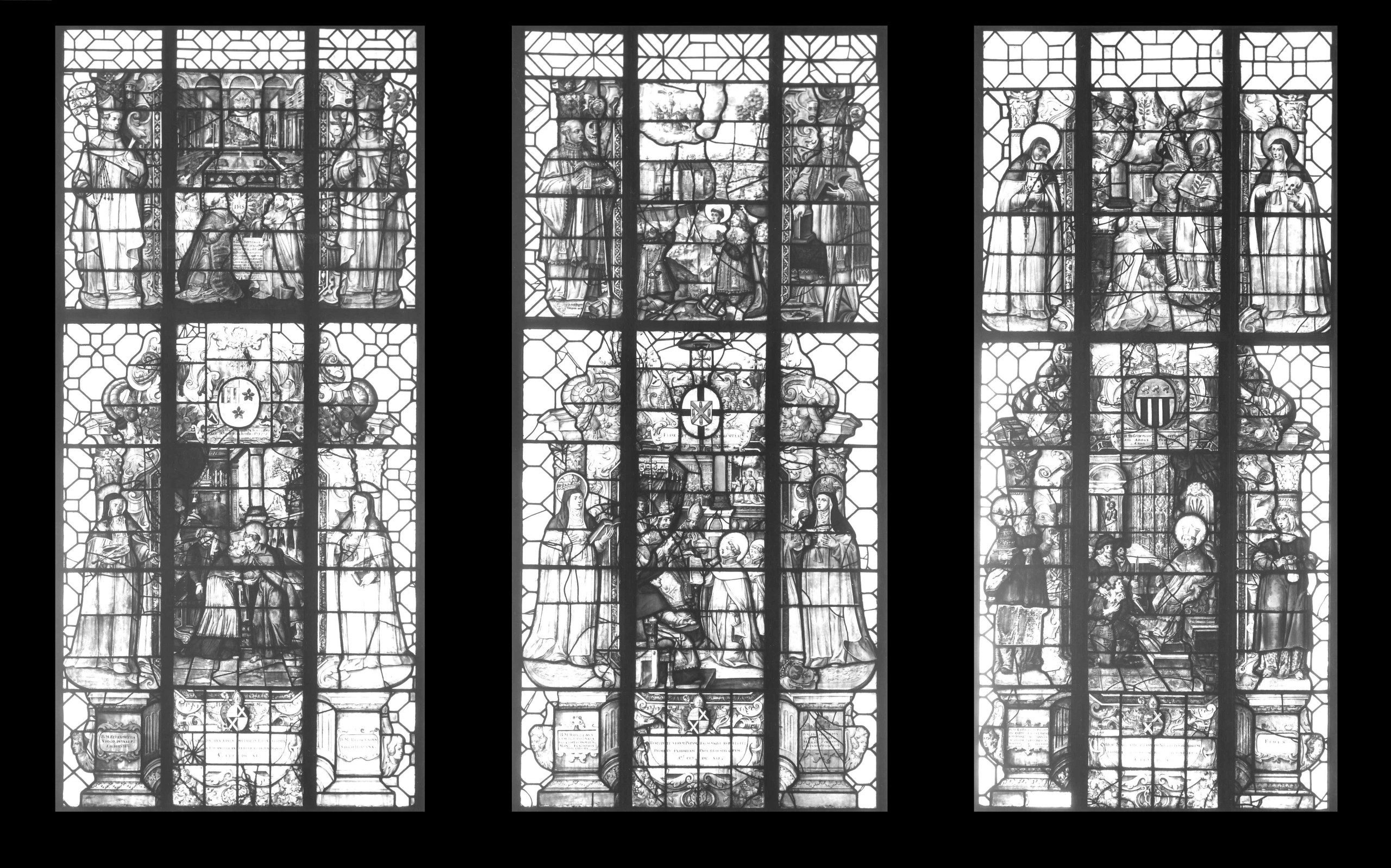

Reconstructing the panel’s original circumstances in detail would require tracing the successive displacements of the glass from religious to secular settings with different audiences, leading me after all to think seriously about the panel’s existence outside the time and place of its origin. It was part of the complex glazing program originally made for the cloister of Park Abbey, a male Premonstratensian house outside the city of Leuven, between 1635 and 1644. The program centered on the life of Saint Norbert, the order’s twelfth-century founder, with references to contemporary events woven through the narrative. Venerated members of the order who lived between the twelfth and seventeenth centuries, like Oda, flanked the narrative scenes, much like the wings of a triptych altarpiece (see Fig. 6). After the patron and artist had realized their visions, the image of a woman with a bleeding face remained before the eyes of several generations of canons for two centuries, until the religious of Park were forced to leave their common life. All of the cloister glass then became a commodity on the art market, a token of culture and social status displayed in grand homes in Brussels, Paris, and New York, and subject to changes in taste and value. Many of the privately held panels were later bequeathed to museums where they languished out of sight for decades in the twentieth century. Close to two-thirds of the glass has now returned to Leuven to be reinstalled at Park Abbey, which has ceased to operate as a religious house and has been transformed into a museum of religious art and a center for Flemish cultural heritage.[2]

The changing contexts of this painted glass panel highlight the tension between the immediate effect of its physical presence and the distance – temporal, physical, and cultural – between the viewer and its origins. As scholars in recent decades have acknowledged and explored the varied perspectives that have formed the discipline of art history, the interpretive role of historical writing and its consequent filtering of our understanding of the past has of course been widely recognized, casting doubt on the possibility of the “objective” study I first attempted as a student.[3] In addition to the documents and texts that provide evidence for historical studies, the field of art history deals with objects and images; their physical presence often evokes a direct, ahistorical reaction from a viewer, adding another type of interpretive lens.[4] Like other forms of historical writing, descriptions and interpretations of works of art inevitably reflect the ideologies of their writers, even when they lay claim to neutrality.[5] More recently, a focus on the materiality of the object has led scholars to examine the agency of objects within social networks, where they become mediators of collective experience. This is a particularly interesting idea for objects like stained glass panels that have moved from religious settings to be displayed as historical artifacts in public and private secular settings.[6]

When I first encountered Oda, art historians were beginning to marshal contemporary critical approaches to interpret premodern works of art. Madeline Caviness’s 1997 essay, “The Feminist Project: Pressuring the Medieval Object,” refuted those who questioned the validity of using modern concepts, such as feminism and psychoanalysis, to study art created in centuries before the articulation of these ideas. Caviness’s thesis would inspire numerous other scholars, and became the basis for the first issue of Different Visions launched by Rachel Dressler in 2008.[7] This work provided a critical beginning to rethinking my approach to the image of Oda.

My purpose here is to re-examine the image of Oda from several perspectives: as a record of the life of a historical person, a seventeenth-century visual interpretation of a 12th-century text, part of a complex glazing program set before the eyes of canons in a cloister, a collected object that conveyed social status, a cultural artifact on public display, and a representation of a figure whose story resonates with modern feminists. Oda’s story has been filtered through the imaginings of writers, religious scholars, and artists. The painted glass panel is one of a very few surviving images of Oda, none earlier than the seventeenth century, and is the only one to portray her at the moment of her self-disfigurement; in others, the short sword and basin become her attributes, referencing this act indirectly. The scene was imagined, first in writing by her contemporary biographer, Philip of Harvengt, and 500 years later by religious scholars who redacted Philip’s text and commissioned artists to realize their interpretations. Through these images, her life is encapsulated in a single, dramatic moment to which there were no witnesses but Oda herself. Yet each iteration, visual and textual, blunts the drama’s reality and spares the observer from confronting a face without a nose. This process began with the vita composed soon after her death.

The historical figure of Oda and early Premonstratensian women

Oda is thought to have been born to noble parents at the castle of Alouette, Thuin, about 50 km south of Brussels, in about 1130; she died as prioress of the Premonstratensian women’s house of Rivreulle, a short distance from her birthplace, in 1158.[8] Her story is known to us through the vita composed, at the request of the nuns of Rivreulle, by Philip of Harvengt, Abbot of Bonne-Espérance, in Hainaut, from 1158 to 1182.[9] Philip tells us that Oda was a devout girl who resolved at a young age to preserve her virginity and dedicate her life to Christ. She confided her plan to a trusted relative, and begged for his help in approaching Odo, Philip’s predecessor as abbot of the nearby Premonstratensian community of Bonne-Espérance, to allow her to join the order. However, her relative betrayed her confidences to her parents, who resolved to find a husband for her as quickly as possible.

Despite Oda’s entreaties, the wedding day arrived, with a host of guests from both families. When it was time to give her consent to marry the young man, she at first remained silent, then at last declared that she would accept no mortal husband and that she had dedicated herself to the love of Christ alone. Chaos ensued, the groom fled, and Oda’s father chased after him, hoping to right the situation. Oda slipped away to her mother’s bedroom where she found a small sword, and, praying for divine assistance, succeeded in slicing through her nose, catching her blood in a small basin. Celebration turned to horror for all but Oda, who was sure she had finally thwarted her parents’ plans for her marriage and would be able to live the life she desired. Her father eventually relented and allowed her to enter the Premonstratensian house, where she came to be highly respected as a spiritual advisor, and gained a reputation for self-deprivation and extraordinary service to the poor and sick.[10]

Care of the sick was a primary activity of early Premonstratensian women, encouraged by St. Norbert, but it soon raised concern among some of his followers.[11] While praising Oda’s charity, Philip’s vita emphasizes claustration over active work, even claiming that a male intermediary carried out charitable work on her behalf. Her spirituality is couched in terms of Biblical exegesis and allusions to verses from the Song of Songs, which serves both as a context for Oda’s self-disfigurement and as a vehicle to transform it into a kind of martyrdom, placing her in the company of martyred virgin saints.[12]

Bonne-Espérance, established in 1126 or 1127, was one of the earliest houses of the Premonstratensian order of reformed canons, founded in 1120 by St. Norbert of Xanten. Like other religious orders in the early 12th century, the Premonstratensians drew many women as well as men, and many of the early Premonstratensian foundations were double houses, with men and women living in separate quarters within the same complex.[13] By mid-century, new women’s houses, at a few kilometers’ remove from the original foundations, were built to separate the sexes; Rivreulle was established for the women from Bonne-Espérance some time between 1140 and 1158, and Oda was made prioress. The separation has routinely been attributed to inappropriate contact between men and women, and most likely there were such instances, but the severity of the separation has been exaggerated.[14] The writings of some Premonstratensian leaders reflect a general unease with the active life for women and the contact it necessitated with the laity, as well as the potential temptations that women within the order represented for male canons. Some began to argue for the strict enclosure of religious women as early as 1130. As Yvonne Seale has shown, however, Premonstratensian women’s communities continued to flourish, and women continued to join the order in considerable numbers through the 12th and 13th centuries.[15] Calls for stricter enclosure do not appear to have had an important effect on the daily lives of Premonstratensian women in Oda’s time. The controversy, however, may be one reason for Philip’s focus on Oda’s claustration and spiritual life, and his hesitancy to portray her caring directly for the sick.

Imagining the moment of self-disfigurement

Oda’s story is the only hagiographical work by Philip of Harvengt that was original, and not a revision of an existing vita, lending it the weight of first-hand knowledge. Linsey Robertson has pointed out that Philip certainly knew his subject personally, but perhaps not as intimately as his description of her inner life might suggest.[16] Philip does not refer to personal conversations; instead, his descriptions of her spiritual life were imagined, set within the literary conventions of vitae of virgin saints. While Oda could herself have been familiar with Premonstratensian preaching on the Song of Songs before she entered the order, this aspect of Philip’s writing may be best understood as a reflection of the common spiritual life of Bonne-Espérance and Rivreulle in the 12th century.[17]

Philip no doubt learned of some of the events he recounts from those who had witnessed them directly, but he chose to emphasize certain events and personal qualities above others, not only so that Oda could serve as an example for others, but also, clearly, to persuade readers of his subject’s saintliness within the context of the contemporary controversy about Premonstratensian women, and nuns in general.[18] His emphasis on the contemplative life may also have been directed toward his immediate audience, the nuns of Rivreulle who were under his care and apparently still participating actively in the care of the sick at Rivreulle.[19]

It would have been difficult for anyone who met Oda to ignore her disfigured face, and thus it may be assumed that the shocking story of her wedding was retold repeatedly. Philip of Harvengt nonetheless had to imagine the nose-cutting scene itself, since Oda was alone at that moment. Writing the story some years after the fact, he created a picture for his reader that would put Oda in the most virtuous light, including, for example, the detail of the basin Oda used to catch her blood, an obvious allusion to Christ’s sacrifice.[20] While this act of self-mutilation is not unique to Oda among medieval women, Philip understood that the circumstances were potentially problematic.

Oda’s story has been analyzed and retold in a number of modern studies of medieval attitudes toward virginity and chastity, as well as of nose-cutting and other disfigurements of the face. The cutting of women’s noses derives from a sense that one’s identity resides in one’s face, and that for women this identity is also a source of sexual attraction. Nasal mutilation has been used as a judicial punishment for sexual misbehavior, but it also became a form of self-defense against sexual aggression; in both cases, destroying the nose is supposed to erase the woman’s problematic sexuality.[21]

In her groundbreaking 1987 article, “The Heroics of Virginity: Brides of Christ and Sacrificial Mutilation,” Jane Tibbetts Schulenburg looked at stories of women who had cut off their noses to protect their virginity.[22] Most of these cases involved communal self-sacrifice to prevent imminent sexual assault by invading enemies, and took place earlier in the Middle Ages, during periods of violent conflict. Hagiographic texts tell us that the entire communities of Saint-Cyr near Marseille, of Coldingham near Durham, and of Saint-Florentine near Ecija, Spain (reportedly some 300 women), cut off their own noses in the face of approaching invaders in the 8th and 9th centuries. While they avoided rape with their actions, all of these woman were murdered by the attackers, and have thus been celebrated as martyrs. The value of their purity was greater than that of their very lives, a topic much discussed by theologians from the Early Church through the middle ages and beyond, many of whom allowed an exception to the prohibition of self-disfigurement and suicide if a woman’s chastity were threatened.[23] It should be noted that each of these events was written down long after it happened, although, as Schulenburg argues, there is evidence to support at least parts of the stories.[24] Whether they are factual or not, however, the true value of the stories was to reinforce the social value of chastity, and to remind listeners or readers in the centuries that followed of the equally great difficulties and rewards of virginity.

Unlike other self-disfiguring women, Oda did not act in the face of assault by an armed invader, but of an arranged marriage. Philip, therefore, is careful to explain that she was unable to cut her own nose until she had prayed fervently for divine help, anticipating possible suspicions that she acted impulsively or in pure self-interest.[25] Young Oda may have been aware of the hagiographic topos of nose-cutting, or simply understood that disfigurement was likely to release her from a marriage contract.[26] As Carol Neel and Lynsey Robertson have noted, Philip carefully prepared the reader for Oda’s nose-cutting with his description of her early spiritual life and with words that compared her to earlier female martyrs, ultimately making the case that Oda, too, was a martyr.[27] Philip of Harvengt’s text equated the defense of virginity with martyrdom. Throughout the Vita Beatae Odae Virginis, Philip is at pains to emphasize the purity of Oda’s motives and the virtue of her actions, turning the reader’s thoughts away from judgment or disgust. Immediately after he describes Oda’s actions, Philip begins to argue that she should be considered a martyr, comparing her to women who committed suicide to avoid being raped, who, “by their voluntary deaths, … prevented the audacious acts of those men, and thereby … purchased the venerable name of martyr with the price of a glorious death.”[28] There are obvious differences between Oda and these women, but Philip conveys the idea that the threat to Oda’s virginity was as dire and as dreadful to her as any other and that, although she did not die from her wounds, she was thereafter dead to the world.

Although Philip’s text seems designed to promote Oda’s cult, the fact that no medieval copies survive points to his failure to inspire veneration beyond the immediate audience of Bonne-Espérance and Rivreulle.[29] Oda’s saintly status has never been confirmed by the Church, but she continues to be celebrated within the Premonstratensian order as Blessed. The text was preserved thanks to Nicholas Chamart, Abbot of Bonne-Espérance in the 17th century, who compiled all of Philip’s writings from the abbey’s archives and published them in 1621.[30] His work was part of a broader effort by Premonstratensians and other religious scholars to document the histories of religious orders and the lives of saints. As 17th-century Premonstratensian historians and hagiographers set about compiling a history of the order, Philip’s vita of Oda became a valuable source for the documentation of one of the first women in the order. That effort was accompanied by the production of the first known images of Oda.

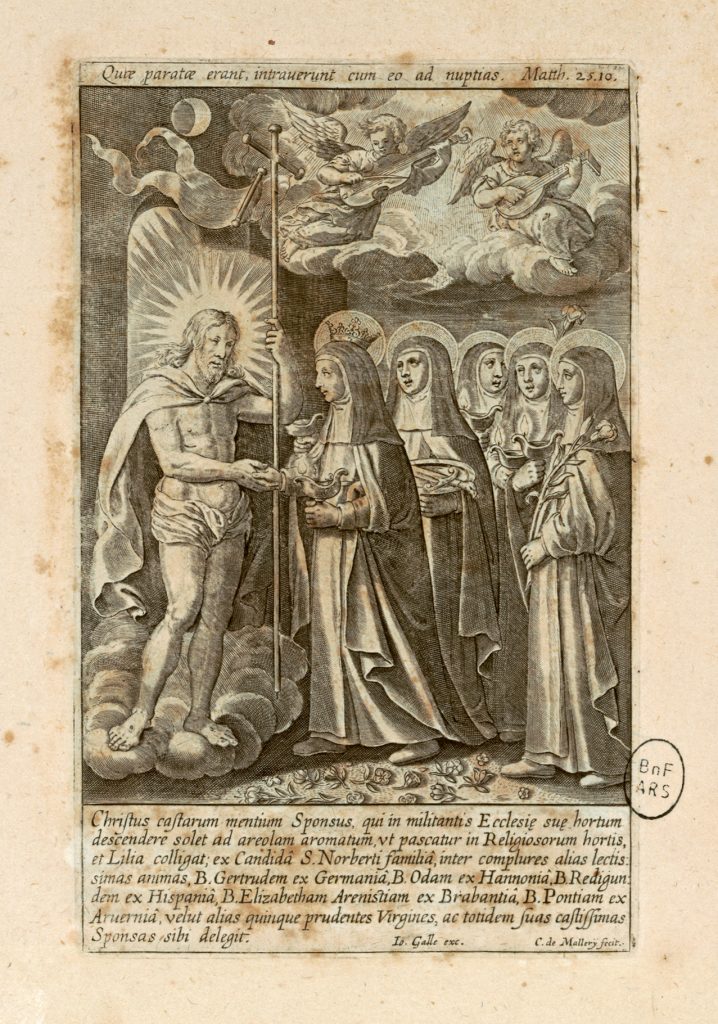

Figure 2. Joannes Galle and Charles de Mallery, Christ receiving five Premonstratensian women. From left to right: Gertrude, Oda, Redigund, Elizabeth of Arnheim, and Pontia. Engraving, c. 1650. ©Bibliothèque nationale de France.

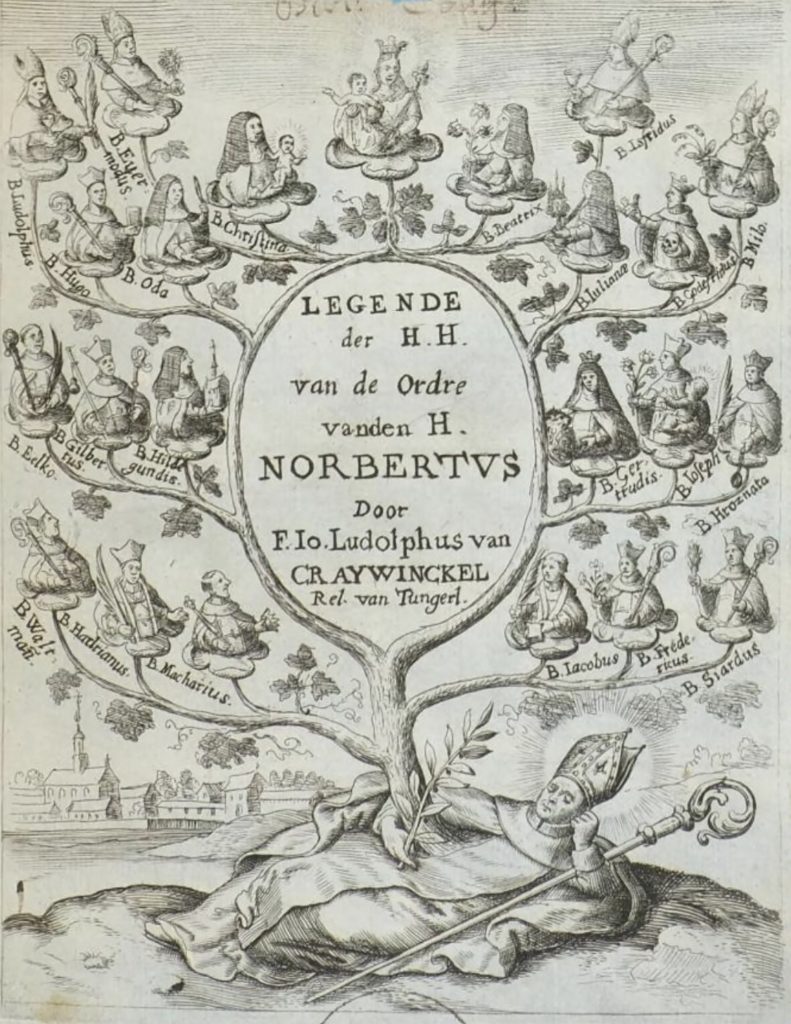

Figure 3. Unknown Engraver, Tree of Premonstratensian Saints, frontispiece from Ioannes Ludolphus Craywinckel, Legende der H.H. van de Ordre vanden H. Norbertus, Antwerp or Mechelen, 1665. © KIK-IRPA, Brussels

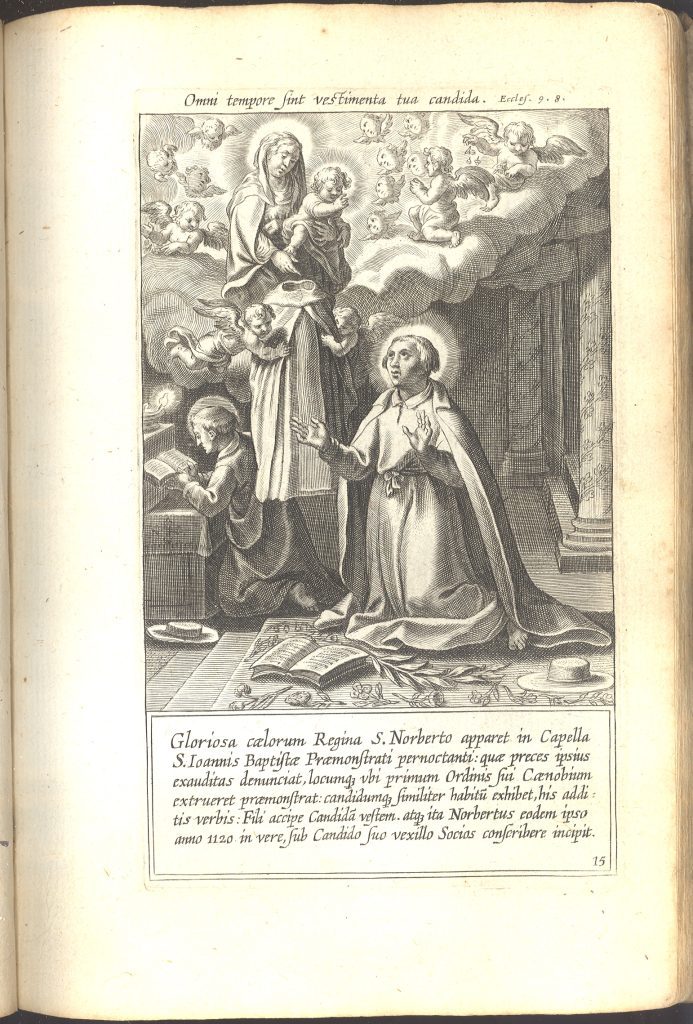

Figure 4. Theodore and Cornelius Galle, after Peter Jode I, St. Norbert receives the white habit from the Virgin Mary, engraving from a copy of J.C. Vander Sterre, Vita S. Norberti, Antwerp, 1623. Archives of Park Abbey.

Text into Image: Self-Disfigurement as a Saintly Attribute

Despite the spiritual context that Philip created for Oda’s self-disfigurement, his dramatic description of her nose-cutting creates a graphic picture in the mind of the reader. No medieval images survive, and with no evidence of a cult beyond Rivreulle and Bonne-Espérance, it is unlikely that there were any. The first images of Oda, then, seem to have been created in the seventeenth century. They drew strongly on this moment in Philip’s text. In addition to the glass panel, two prints survive. Figure 2 depicts Christ receiving five Premonstratensian sisters in a composition clearly based on the familiar tradition of the Wise and Foolish Virgins; the accompanying text compares them to “the other five wise virgins.” Oda, second from the left, holds a basin with a dagger balanced on its rim, in a manner similar to the painted glass image, but now, removed from any sign of trauma, it becomes a simple attribute. The second print is a tree of the followers of St. Norbert, modeled on the Tree of Jesse, which includes Oda on a branch at the upper left, veiled and again holding a basin and dagger as attributes (fig. 3).

Both prints were created in Antwerp, an important center for the production of prints at the time. They were reproduced numerous times over the course of the seventeenth century, bound in books in various combinations with other images and texts.[31] The image of the “five wise virgins” was first printed by Theodore and Cornelius Galle, and bears close comparison to the set of 35 engravings of the Life of St. Norbert, which they produced on commission for Johannes Chrysostom van der Sterre, canon and later abbot of St. Michael’s Abbey in Antwerp.[32] The engravings of Norbert’s life also later served as models for narrative scenes in 35 of the 41 windows at Park (fig. 4). Van der Sterre himself composed a life of St. Norbert from manuscript sources, first published in 1622 and reprinted in several editions and in multiple languages through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, sometimes accompanied by the Norbert engravings and those of other venerated Premonstratensians including Oda.[33] Printers in Antwerp were especially prolific in producing small books of the lives of saints, as well as iconic images of individual saints, with monastic libraries and individual religious among their primary customers.[34] While the commissions for images of other Premonstratensian saints are not documented like the images of Norbert, the similar format and style suggest that the image of the five virgins was created close to the same time, that is, in the early 1620s. An early version of the tree was commissioned by Jan Maes, then Prior of Park, in 1617.[35] Several different versions were produced for different abbeys, with variations in the figures represented.[36]

These Premonstratensian images and the hagiographic studies that accompanied them are only a small portion of the production of historical and hagiographic texts and images of all religious orders in this period of Catholic renewal, in the wake of the turmoil of the Reformation and in response to the dictates of the Council of Trent on images and the veneration of saints.[37] The appearance of images of Oda and the redaction of Philip of Harvengt’s writings were both part of that larger effort. The renewed interest in both Philip and Oda in the 17th century reflects the concerns of that time.

The Seventeenth-century Context: The Cloister of Park Abbey, 1635-44

In the cloister of Park Abbey, Oda was one figure among 40 pairs of venerated Premonstratensians. The cloister was rebuilt and glazed when the canons returned to Park Abbey in the summer of 1635, after the siege of Leuven by French and Dutch forces, which left parts of the abbey in ruins.[38] Abbot Jan Maes, recently elected to lead the abbey, drew on his own extensive study of Premonstratensian history in conceiving the program of 41 windows that would encircle the new cloister.[39] Maes, a native of Leuven, had studied at the University of Louvain and exemplified the spirit of learning that characterized Park at that time.[40] He hired the glass painter Jean de Caumont to carry out his vision. Born in Doullens, France, to a family of stained-glass artists, Caumont had settled in Leuven in 1607 and became the city’s preeminent glass painter.[41] Surviving account books kept by Abbot Maes document the installation of completed windows; the last were placed in the south aisle in 1644. [42]

The original placement of panels can be reconstructed with some certainty.[43] Starting in the northeast corner and moving clockwise, a narrative scene from the life of St. Norbert occupied the central panel of each window, progressing from his birth around 1075-80, through the foundation of the Premonstratensian order, to his accession to the seat of Archbishop of Magdeburg, and culminating in the translation of his relics to Prague in 1627 (figs. 5 and 6). Below each scene is a decorative cartouche with a couplet describing the scene.[44] Heraldic panels mounted above the narrative scenes represented the succession of abbots of Park from 1129 until 1635, leaving room for a few later additions.[45] Two narrow panels, each containing a single figure of a venerated member of the order, flanked the central scenes. Each figure stood on a pedestal inscribed with the name, feast date, and often the house where the person lived, or a reference to an event. They were paired according to rank–conversi, canons, canonesses, and abbots–regardless of the time in which they lived; unlike the other elements, the standing figures were arranged thematically rather than chronologically.

Figure 5. Park Abbey, Heverlee, Leuven, cloister before restoration. Photo: Author.

Figure 6. Jean de Caumont, A wolf tamed by St. Norbert’s holiness becomes a protector of the sheep at Prémontré, with St. Peter van Kalmpthout and Bl. Arnaldus Swalma, from the cloister of Park Abbey, 1641. Belgium, Private Collection. Photo: Isabelle Lecocq.

A total of fourteen figures–seven pairs–of female Premonstratensians are documented in modern collections. On the basis of ornamental detail and of descriptions locating tombs in the cloister, it is clear that the women were all placed in the north cloister aisle, next to the church. The north side of church buildings had long been associated with women, both as the real space to be occupied by female worshippers and, through imagery and textual description, in an imagined mapping of a bi-gendered cosmos onto the church building.[46] At Park it seems this idea of gendered space was apparently extended to the cloister decoration.[47] The fourteen known female saints would have occupied seven of the nine windows in the north aisle, while one contained female allegorical figures of Faith and Patience. Two additional female figures, now lost, must have completed the remaining window.

The north aisle is an interesting choice for images of women, for it is there that the canons engaged in daily devotional readings both individually and as a community.[48] Five of the female figures hold books, apparently in acknowledgment or encouragement of the daily activity before them (fig. 7). Thirty of the 64 male figures who filled the side panels of the other three wings survive. Only two hold open books, and they are dressed in liturgical copes, with the words of prayers to the Virgin emanating from their mouths; in other words, they hold books in an act of liturgical performance, and not for contemplative reading. The images of women reading, alongside others who hold crucifixes, rosaries, and other devotional objects, are a visual parallel to Philip’s textual emphasis on Oda’s spirituality and claustration.

Figure 7. Jean de Caumont, Blessed Gertrude reading, detail, stained-glass panel from Park Abbey, 1639. Photo: Author.

Unlike the dark north side of a church interior, the north wing of a cloister receives light from the south, and is thus the best-lit place for reading. The form and placement of the seats are unknown. For the light to fall on the page of a book, a reader would have to be seated either sideways or with his back to the window. Thus the opportunity to look at the windows would have come as one was approaching or leaving the bench, but not while reading. It is unlikely that a canon would have spent an extended period gazing at Oda’s image. Nonetheless, it would be difficult to ignore. Its scale and color enhance a dramatic effect common to many Counterreformation images of martyrs, reflecting the concerns of the seventeenth-century Church in general and the Premonstratensians in the Southern Netherlands in particular.

Martyrs in a Time of Sectarian and Political Violence

The violence communicated by Oda’s image would have resonated with the real experience of the canons of Park, who had lived through the political and religious wars of the sixteenth and early seveneenth centuries. The Franco-Dutch Siege of Leuven in 1635 wreaked significant damage upon the abbey’s buildings. While the community sheltered at their refuge within the city of Leuven, they witnessed fighting in the streets and bodies left behind by the retreating forces. Eight canons of Park died in the following year, presumably from illnesses they contracted from exposure to the wounded and sick.[49] Within recent institutional memory, Leuven had been the site of several other battles between the forces of the Spanish crown and the Dutch rebels led by William of Orange. In 1566, the Duke of Alba quartered his troops at Park; in 1572, William of Orange did the same. To punish local residents for aiding the enemy, the notorious Duke of Alba executed a local magistrate by ordering him hanged from a tree on the grounds of Park Abbey.[50] While few if any canons alive in 1640 would remember these events personally, first-hand knowledge of these events had certainly been passed down from their predecessors.

In his chronicle of the abbey published in 1666, Abbot Jan Maes’s successor, Libertus de Pape, described the cloister glass in verse, including these lines about the standing figures of venerated Premonstratensians:

Omnibus expertes vocis sine voce loquuntur,

Bina loquuntur idem Romanis carmina verbis.

Omnis & appictis hinc inde duobus imago[51]

[The voices of those who have been tested speak silently,

In pairs they chant in Roman words

All portrayed here two by two]

The idea of fellow Premonstratensians who had been tested was not remote; in addition to the violence the canons had witnessed in Leuven, the Reformation had created martyrs on both sides, including Premonstratensian canons who were memorialized in the glass. In all, six of the documented standing male figures were martyrs, including two from the Middle Ages, and at least three who had been killed by Protestants in the previous century. Theodore Schlegel, tortured and executed by Protestants in Chur, Switzerland, on 23 January, 1529, simply holds a martyr’s palm and sword. James Lacops, one of the nineteen martyrs hanged by Calvinists in Gorkum, Netherlands, on 9 July 1572, is depicted in a preparatory drawing holding a palm and a monstrance, while his image in a glass panel has not been definitively identified; a figure holding a palm, a burning book and papal keys may represent either James or the second Premonstratensian hanged at Gorkum, Adrian Janssens.[52] Peter van Kalmpthout, who was tortured by Dutch rebels who broke into his church in Haaren on 16 April 1572, and finally beheaded when he refused to renounce Catholicism, was portrayed with two swords lodged in his body, one across the top of his skull and the other in the left side of his chest, with blood flowing from each wound (Fig. 8). Peter was actually beheaded with an axe. The choice to deviate from this documented fact and place two swords so that blood flows down his face and from his breast is clearly meant to evoke the crucified Christ. The image of Peter van Kalmpthout was placed on either the south or west aisle of the cloister, but his bleeding face echoes that of Oda and helps to further emphasize the idea of Oda as a martyr. As has already been noted, the basin that Oda holds to catch her own blood is an obvious Eucharistic reference. The two figures make visual the association of martyred saints with the crucified Christ.

Figure 8. Jean de Caumont, Peter van Kalmpthout, detail of fig. 6. Photo: Isabelle Lecocq.

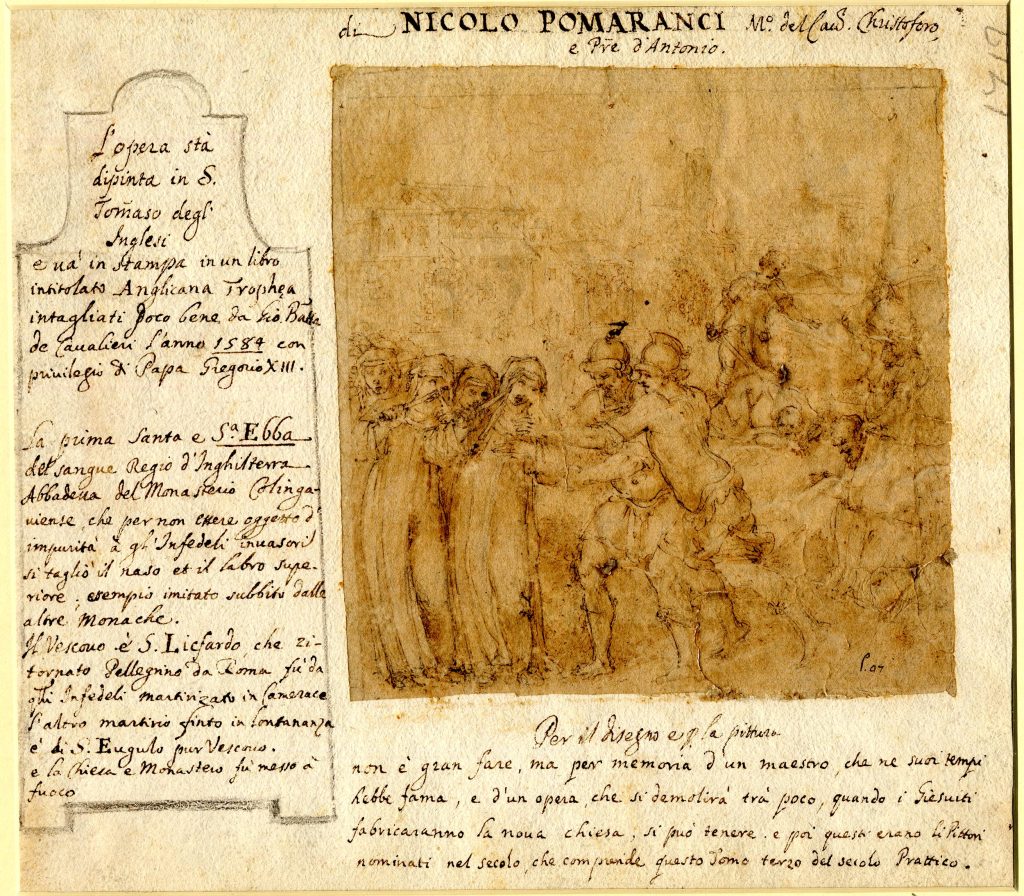

Oda and Peter both appear calm in the face of their injuries, as martyrs were frequently depicted in the Middle Ages and the early modern period, to suggest that their spirituality afforded them divine protection against earthly woes, and that their attention was already turned toward heaven. In this, of course, they also imitate Christ. All of the standing figures from the Park Cloister are, additionally, iconic figures. While the panels may include various objects that allude to their lives, or even sunbursts of divine vision, they remain outside any earthly narrative. Artists in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries otherwise created some of the most painful narrative images of martyrdom, as can be seen particularly in the work of Francisco Zurburan in Spain and of Hieronymus and Ambrosius Francken in Antwerp.[53] More graphic still is the Theatrum Crudelitatum Haereticorum Nostri Temporum, an illustrated description of the horrors visited upon Catholics in England, France, and the Netherlands by Protestants, written and published by Richard Verstegen in Antwerp in 1587.[54] Paintings created by Niccolò Circignani in the 1580s for the church of St. Thomas of Canterbury at the Venerable English College in Rome similarly highlighted violent death, on a monumental scale. The college trained priests who would return to England as missionaries at a time when Catholicism was outlawed and severely punished there. At the English College, narrative images of the martyrdoms of English saints from the early middle ages up to the present moment might have helped to strengthen the resolve of future missionaries for the dangerous lives they had chosen.[55]

The designers of the Park cloister program, Jan Maes and Jean de Caumont, chose not to portray the martyrdoms in such a gruesome way, but rather to present the figures of martyrs within a serene procession of Premonstratensians in heaven. The glazing program, created more than fifty years after the Venerable English College cycle, focused on triumph over tribulation. Not only was the glass the jewel of the newly restored abbey, but its narrative of Norbert’s life ended with the translation of his relics from Magdeburg to Prague in 1627, just eight years before the cloister was conceived. This event, marked by elaborate public ceremonies and mass conversions, was a defining moment for the restoration of Catholicism in Prague, and a victory for the Premonstratensian order in particular.[56] Oda stood in this context as one of the witnesses to that triumph as well as the orthodox Catholic doctrine of triumph over death.

Figure 9. Niccolò Circignani, St. Aebba and the nuns of Coldingham cutting off their noses, drawing for a wall painting in the church of St. Thomas of Canterbury in Rome, c. 1582. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

The Unsevered Nose

Among the monumental paintings in the chapel of the Venerable English College was an image of St. Æbba with the nuns of Coldingham cutting off their noses as they are attacked by Vikings. While the original paintings were destroyed, drawings and prints survive and show that the nuns of Coldingham were depicted without noses (fig. 9). On a larger scale, this must have been quite shocking, and makes most sense in the context of ongoing violence, where the visual program was meant to emphasize its horror. The image breaks with the more common practice in art of the early modern period of depicting female martyrs with their bodies unbroken and their faces intact, emphasizing the purity that gave them entrance to heaven over the violence that ended their mortal lives. The Park panel of Oda falls somewhere between the violence in the images from the Venerable English College and the serene, unblemished female martyr, since her face bleeds quite profusely. Her nose, however, remains intact.

In the two print images, Oda’s attributes are established as the basin and dagger, and the dramatic story of her nose-cutting becomes the moment of her life that is highlighted above the rest. Her chastity, as is evident from the “five wise virgins” image, is an essential part of this act, but the use of the basin and dagger as attributes foregrounds the cutting itself. Yet the loss of the nose is merely implied by the dagger, in the case of the prints, and by the flowing blood in the glass panel. Unlike saints who lost other body parts, saints who lost their noses are almost never depicted without them; nor do they hold severed noses as attributes, as St. Lucy, for example, sometimes holds her eyes. There are no nose relics preserved like such other soft tissues as the breasts of St. Agatha or the tongue of St. Anthony.[57] There is no patron saint specifically for nasal problems. There are several possible reasons for the avoidance of nasal-disfiguring imagery. It has been argued that a face without a nose is physiologically difficult to look at, and that the loss of a nose leaves a face without identity. Frederika Bain suggests that, since nasal mutilation is an ambiguous sign, possibly marking its bearer as a prostitute or adulteress, the didactic lesson of such an image could be equally ambiguous.[58]

The three images of Oda do not seem to have engendered wider artistic representation, although it is possible that other images were lost. Modern images designed to aid veneration tend to be generic figures of a young female saint without reference to her nose-cutting, with the recent exception of a sculpture of Oda holding a severed nose as an attribute (but with face intact) made for St. Norbert Abbey in Wisconsin, but this is an entirely new invention, created in the twenty-first century.[59]

The expected audience is important. While the prints with Oda’s image were widely available, the more startling image on glass was unique, and placed in a cloister accessible only to male canons. Oda certainly served as an example of chastity for both male and female Premonstratensians, and the portrayal of her self-mutilation acknowledges the battle against the secular world and one’s own body that chastity requires. Oda disfigured her face to prevent male arousal, and looking at such an image might itself serve that purpose for a religious male intent on fighting against his own desires. The nose itself however, also has sexual connotations, so that showing it disfigured might be inappropriate for a religious image in a cloister.[60] In addition, an image of a woman’s tortured body has a potentially pornographic effect, as has been explored by Martha Easton and Madeline Caviness, particularly for Saint Agatha.[61]

There is contemporary evidence of hesitancy to evoke Oda’s severed nose directly in text as well. Johannes Chrysostom van der Sterre published a short book of Premonstratensian saints, arranged according to their place in the liturgical calendar, in 1625. The entry for Oda only alludes to her disfigurement as a “marvelous strategem” by which she escaped the passions of this world “so that she could be received intact by her heavenly spouse,” without any more specific description.[62] This book was quite generally accessible, in contrast to Philip of Harvengt’s text, which would be read only by learned hagiographic scholars. The difference between the two texts seems akin to the difference between the “five wise virgins” image and the bleeding face of the stained glass, which were also available to audiences with different levels of knowledge and sophistication.

In its original context, the visibility of the image and the character of the audience was controlled. If the violent implications of the bleeding image were meant for a restricted audience, however, this would change drastically when Park Abbey was suppressed. Its glass was sold at a time when Flemish sixteenth- and seventeenth-century glass was especially popular among collectors.

Secular Contexts

Two descriptions of the glass offer the perspectives of very different viewers. While Libert de Pape recorded the religious subjects of the cloister windows in detail and with reverence in 1666, American architect Stanford White presented a very different picture to his client William C. Whitney, whose house on Fifth Avenue in New York he was redesigning and furnishing. Writing from Paris in 1898, White described an architectural problem to be solved: “The end of your hall is nothing but a screen of marble columns and glass which must be obscure, and upon the successful treatment of which much of the success of the hall will depend.” He asked permission to buy some “beautiful old 15th century painted glass with historical subjects – from a Renaissance chapel…” for this purpose.[63] White knew very well that the glass was seventeenth-century, and came from the Abbey of Park, but the religious subjects would not appeal to Whitney, and the earlier date would better fit his desire to imitate an Italian Renaissance villa.[64] In other words, the description was calculated to appeal to his client’s taste and convince him to spend 150,000 francs.[65]

Park Abbey had been suppressed by the French Revolution. In 1828, the cloister glass was sold to a Brussels shipping magnate, Jean-Baptiste Dansaert.[66] The windows were divided into several groups as they were passed down to Dansaert’s heirs until, by the end of the nineteenth century, most had been sold to different collectors in Belgium, France, and England. In about 1890, the Viscountess of Janzé had as many as fourteen of them installed in stairway, hall, and diningroom windows in her Paris hôtel on the rue Marignan.[67] Stanford White visited the house and fell in love with the Park windows.

The Park glass has qualities that perfectly fit Stanford White’s requirement of modulating the light. Jean de Caumont incorporated colored glass in his work, but he was a master of the relatively new vitreous enamel paint, which was generally more translucent. He used it to great effect along with the brilliant yellows of silver stain and the delicate pinks created with thin washes of dilute iron oxide. He also used grisaille paint on both sides of clear glass to create the illusion of textures. Caumont was, in short, a master of seventeenth-century glass painting techniques, which became a factor in the market value of his work. It is clear from White’s correspondence that the specific subject matter and its religious significance were of little interest. The presence of heraldic panels as well as cornucopiae and putti were surely of greater importance for an American client who wanted to present himself as a peer of sophisticated European aristocracy. William Whitney did agree to the purchase, and the glass was shipped to New York and rearranged by artist Francis Lathrop to fit into a large window filling the wall in front of a grand marble staircase. Since the windows were all of about the same dimensions and consisted of nine rectangular panels, some rearrangement no doubt took place in the original process of dismantling and moving them, and the rectangular panels from Park could be easily separated to fit domestic interiors. In Whitney’s new home, approving journalists described the composition as “a beautiful arrangement of stained glass, which was once part of the chapel of the palace of the Viscount Sauze,” the fictional person and place White apparently invented to give the glass a loftier provenance as well as to protect the real seller’s identity.[68]

The Oda panel was not part of this composition, but other scenes, including an exorcism, St. Norbert and his early follower, Hugh of Fosse, speaking with Christ, and the Virgin giving Norbert the white habit of the Premonstratensian order, are hard to describe as “historical.” They seem extraordinarily out of place in a space that served to greet and entertain New York’s leading socialites. Whitney held several large banquets and balls in the short time he lived in the house, sometimes placing musicians on a temporary platform at the top of the stairs, directly in front of the glass, but neither he nor his guests, nor any of the subsequent owners up to 1942 when the glass was removed, left a any comment that would indicate that anyone noticed the subjects.[69]

The panel of Oda of Rivreulle was part of another group of windows installed a few years later in a New York mansion famous for its extravagance. This was the enormous Beaux-Arts mansion built on the corner of 5th Avenue and 71st Street – just three blocks north of the Whitney house — by the former senator from Montana and copper-mining magnate, William Andrews Clark. Clark left no records to tell us where he bought his glass; he could have acquired it himself in France, or it may have come to him from Stanford White through the Duveen Brothers, who furnished most of the interior.[70] Clark was himself a great francophile, and amassed an impressive art collection through his own research as well as contacts with dealers. The stained glass from Park that Clark acquired was placed in his library windows. Clark’s daughter Huguette recalled fondly looking at stained glass from a monastery as a child playing in the library, but she gave no further details.[71]

In contrast to Whitney’s stair hall window, where eight different windows were jumbled together, the original window compositions were largely retained in two rows of three windows at the Clark mansion (fig. 10). The visual logic of Clark’s glass was still somewhat confused, however, since three of the windows were truncated by removing the lower register, and then attached directly above three others.

Figure 10. Stained glass from Park Abbey at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, arranged as previously installed in the library of the William A. Clark House until 1927. Photo: Corcoran Gallery of Art.

An additional Park panel, now lost, belonged to William Rockefeller, another resident of Fifth Avenue.[72] Stanford White himself had parts of five Park windows in his possession at the time of his death in 1905.[73] They were purchased from his estate by several other American collectors, including William Randolph Hearst.[74] For all of the American collectors, whose wealth was gained through business ventures, the Park glass was among the material objects used to create an air of aristocracy. While Europeans criticized these collectors for their lack of sophistication in displaying objects out of context, arguing that only those with an upper-class lineage could truly appreciate such things, it is worth noting that the Americans closely imitated the displays of stained glass they saw in the homes of European aristocrats.[75] On both sides of the ocean, collections of medieval and early modern stained glass marked their owners as part of an elite social group. The intellectual and spiritual ideas the windows communicated in the cloister were of little interest.

The Park glass was out of fashion by 1930, and did not fit easily into the traditional art-historical categories, where highly prized stained glass was medieval and greatness in Baroque painting was restricted to opaque media. At the end of the twentieth century, panels could be found in three American museums, where they had arrived as part of larger bequests. Whitney’s glass was divided between the Speed Museum in Louisville, Kentucky, where it is on exhibit today, and Yale University Art Gallery, where it remained in crates until 2013, when it was sold to the Flemish Ministry of Culture. William Clark left his collection to the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C., but by mid-century the gallery that held the glass had ceased to be accessible to the public. Clark’s glass was also returned to Belgium when the museum closed in 2016. The glass from Yale and the Corcoran Gallery will join six windows returned earlier in the twentieth century, and the restored cloister will be open to the public as part of a museum, since Park no longer functions as an abbey. With many panels still missing, it is not practicable to put everything back in its exact location, and thus viewers will not be able to appreciate fully the relationships among the images as they were originally configured, nor will they be able to see them through the eyes of seventeenth-century canons. The restored cloister is a monument of Flemish cultural history. Most visitors will no doubt appreciate the artistic qualities of the glass, and may gain a sense of the complex threads of history woven through the original program thanks to the extensive research that will be incorporated into the installation.[76]

Conclusion

The image of Oda has travelled from Park Abbey to Brussels, Paris, New York, and Washington, and home again, although that home is very much changed. Contemporary scholarship recognizes the essential importance of the physical and contextual changes that works of art accrue over time, and begs us to consider the reasons for and the effects of their continued existence as multiple viewers interact with them. Without the words of other viewers, we are left to observe the incongruities of image, time, and place. And so I return to my own familiarity with the Park Abbey glass and particularly with the figure of Oda, whose bleeding face impressed itself firmly in my mind’s eye, and ask why she has “stuck to my skin” so tenaciously.

Despite the silence of modern collectors, the image of a bleeding face is likely to provoke a visceral reaction in any viewer who notices it. In fact, Oda’s separation from the full context of the Park cloister helped to draw my attention in the Corcoran Gallery. From a modern viewpoint, the idea of cutting off one’s nose to become a nun seemed, thankfully, arcane. Yet I now recognize that before I knew who the woman was I reacted with a sympathetic recognition. Like Oda, I was well aware that navigating the world behind a youthful female face could provoke aggression. Her bleeding face is a poignant reminder of the consequences of that aggression that continue today, across cultures.[77] Oda went to an almost-unthinkable extreme in order to choose her own path in life, but the gender-based social expectations that underlay her actions are familiar enough. While this image is little known, Oda’s story has resonated with numerous modern scholars who study gender issues as well as representations of violence and disfigurement; I would suggest that its power lies in its ability to touch common feelings of vulnerability that transcend time, place, gender, and personal circumstance. Although they may spring from the same essential shock of recognition, the reactions of modern viewers and readers differ in many ways from those of a seventeenth-century Premonstratensian canon. The continued physical presence of the images, along with the preservation of Oda’s story in text, compels a continuing confrontation with her self-disfigurement.

References

| ↑1 | Georges Didi-Huberman, Confronting Images: Questioning the Ends of a Certain History of Art, Preface to the English Edition: “The Exorcist,” trans. John Goodman (University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State Press, 2009), p. xxiii. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | For details of the recent history of the glass, see Janick Appelmans and Leo Janssen, “Als puzzelstukjes op hun plaats vallen. De terugkeer in situ van de zeventiende-eeuwse glasramen van de Parkabdij,” Eigen Schoon & de Brabander. Driemaandelijks tijdschrift vanhet Koninklijk Historisch Genootschap van Vlaams-Brabant en Brussel 103 (2020): 125-42; Ellen M. Shortell, “Visionary Saints in the Gilded Age: The American Afterlife of the Park Abbey Glass,” in Collections of Stained Glass and their Histories, Transactions of the 25th International Colloquium of the Corpus Vitrearum in Saint Petersburg, The State Hermitage Museum, 2010, ed. T. Ayres, B. Kurmann-Schwartz, C. Lautier, and H. Scholz (Bern: Peter Lang, 2012), pp. 239-53; eadem, “Stained Glass from the Corcoran Gallery to Return to Park Abbey,” Vidimus 93 feature, 2015, http://vidimus.org/issues/issue-93/feature/; Isabelle Lecocq and Ellen Shortell, “Les vitraux de l’abbaye de Parc (Heverlee, Louvain) conservés à Bruxelles, témoins majeurs de l’art du vitrail du XVIIe siècle dans les anciens Pays-Bas du Sud,” Revue Belge d’archéologie et d’histoire de l’art / Belgisch Tijdschrift voor Oudheidkunde en Kunstgeschiedenis 83 (2014), pp. 115-50; and Aletta Rambaut, Marc Vanderauwera, Ellen Shortell, Sarah Jarron, and Katrien Mestdagh, “The Masterpiece of Jean de Caumont returns to Park Abbey (Heverlee-Leuven, BE): Status Quaestiones of research into the reconstruction/relocation of the stained glass in the cloister,” in Stained-glass: how to take care of a fragile heritage? Acts of the Forum for the Conservation and Technology of Historic Stained Glass (Paris: ICOMOS France, 2015), pp. 110-16. |

| ↑3 | The bibliography on the subject is now extensive. Foundational works include Roland Barthes, “The Discourse of History”(1968), in idem, The Rustle of Language, trans. Richard Howard (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989), pp. 127-41; Michel Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (New York: Vintage Books, 1973); Hayden White, The Content of the Form: Narrative Discourse and Historical Representation (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987); and Michel de Certeau, L’Écriture d’histoire (Paris, Editions Gallimard, 1975). |

| ↑4 | On the problem of historical distance and material presence in art history, see Georges Didi-Huberman, Confronting Images; Keith Moxey, Visual Time: the Image in History (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2013), and “Impossible Distance: Past and Present in the Study of Grünewald and Dürer,” Art Bulletin 86 (2004): 750-63; Alexander Nagle and Christopher Wood, Anachronic Renaissance (New York: Zone Books, 2010); Transparent Things: A Cabinet, ed. Karen Eileen Overbey and Maggie M. Williams (New York: Punctum Books, 2013); and Scraped, Stroked, and Bound: Materially Engaged Readings of Medieval Manuscripts, edited by Jonathan Wilcox (Turnhout: Brepols, 2013). |

| ↑5 | Janet Marquardt, Introduction, Medieval Art and Architecture after the Middle Ages, ed. Janet Marquardt and Alyce Jordan (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011), pp. 1-17 provided an overview of this process in the historiography of medieval art. Marquardt evoked the concept of “cultural memory” as conceived by Aleida and Jan Assmann, to describe the accumulation of historical lenses that mediate our knowledge of medieval art history. See Jan Assmann and Rodney Livingstone, Religion and Cultural Memory: Ten Studies (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2006) and Aleida Assmann, Cultural Memory and Western Civilization: Functions, Media, Archives (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012). |

| ↑6 | Grażyna Jurkowlaniec, Ika Matyjaszkiewica and Zuzanna Sarnecka, “Art History Empowering Medieval and Early Modern Things,” in The Agency of Things in Medieval and Early Modern Art: Materials, Power, and Manipulation, edited by Grażyna Jurkowlaniec, Ika Matyjaszkiewica and Zuzanna Sarnecka (New York: Routledge, 2018), pp. 3-12; Bruno Latour, Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network Theory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315166940-1 |

| ↑7 | Different Visions 1 (2008) “Triangulating our Vision,” guest editor Corine Schleif, was inspired by Madeline H. Caviness, “The Feminist Project: Pressuring the Medieval Object,” Frauen Kunst Wissenschaft 24 (1997): 13-21; Visualizing Women in the Middle Ages: Sight, Spectacle, and Scopic Economy (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), 30-34; and Reframing Medieval Art: Difference, Margins, Boundaries, Introduction. |

| ↑8 | Philip of Harvengt, Vita Beatae Odae Virginis, in D. Philippi abbattis Bonae-Spei… Opera Omnia, edited by N. Chamart, J.P. Migne, P.L., 203, col. 1360-61. Bonne-Espérance and Rivreulle are about 12 km to the west of Alouette, and less than 5 km apart. On Rivreulle, see Dom Ursmer Berlière, “L’Ancien monastère des norbertines de Rivreulle,” Messager des sciences historiques de Belgique 67 (1893): 381–91. Oda of Rivreulle is sometimes referred to as Oda of Hainault, Brabant, or Anderlues. She should not be confused with Oda of Scotland, Oda of Aquitaine, or Oda of Huy, who are believed to have lived in the sixth, eighth, and thirteenth centuries, respectively. |

| ↑9 | Studies of Oda’s vita include Lynsey E. Robertson, “Philip of Harvengt’s ‘Life of the Blessed Virgin Oda’,” Journal of Medieval History 36 (2010): 55-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmedhist.2009.11.002; and Theodore J. Antry, O. Praem., and Carol Neel, Norbert and Early Norbertine Spirituality (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 2007), pp. 191-214. |

| ↑10 | Migne, P.L. 203, col. 1361-65. The annotated Bollandist version is in AA SS April, vol. 2, 772-80. An English translation is included in Antry and Neel, Norbert and Early Norbertine Spirituality, pp. 194-214. |

| ↑11 | Norbert left Prémontré to become Archbishop of Magdeburg in 1126, appointing Hugh of Fosse as his successor; it was under Hugh’s leadership that the first true rules were composed, including restrictions on women’s activities. See Carol Neel, “The Origins of the Beguines,” Signs 14 (1989): 321-41, esp. 331-38; and Antry and Neel, Norbert and Early Norbertine Spirituality, pp. 193-94. |

| ↑12 | Antry and Neel, Norbert and Early Norbertine Spirituality, pp. 172 and 194-95; Robertson, “Philip of Harvengt’s ‘Life of the Blessed Virgin Oda’,” esp. pp. 67-71. |

| ↑13 | Bruce L. Venarde, Women’s Monasticism and Medieval Society: Nunneries in France and England, 890-1215 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997), pp. 207-09. There is no evidence to suggest that Park Abbey was a double house. |

| ↑14 | Yvonne Kathleen Seale, “ ‘Ten Thousand Women’: Gender, affinity, and the development of the Premonstratensian order in medieval France,” Ph.D. thesis, University of Iowa, 2016 (https://doi.org/10.17077/etd.ho4du1nz), pp. 176-94, shows that close communication between the male canons and female religious continued at Bonne-Ésperance and elsewhere. |

| ↑15 | Seale, “ ‘Ten Thousand Women’,” pp. 57-122, reviews the sources that have been interpreted as evidence of the strict claustration of women in the Premonstratensian order, and convincingly refutes the traditional narrative of the ejection of women from the order. |

| ↑16 | Robertson, “Philip of Harvengt’s Life of the Blessed Virgin Oda,” 59, argues this point quite convincingly. It was Phillip’s predecessor, Abbot Odo, who welcomed Oda to the community and spoke with her directly. Philip’s absence from Bonne-Espérance from 1149 to 1151 also surely limited their relationship. On Philip’s life, see G.P. Sijen, “Philippe de Harveng, abbé de Bonne-Espérance: sa biographie,” Analecta Praemonstratensia 14 (1938): 37–52. |

| ↑17 | Antry and Neel, Norbert and Early Norbertine Spirituality,” pp. 191-92; Robertson, “Philip of Harvengt’s Life of the Blessed Virgin Oda,” 59. Philip’s treatise on the Song of Songs, which preceded his Life of Blessed Oda, has been treated in depth by Rachel Fulton, From Judgment to Passion: Devotion to Christ and the Virgin Mary, 800-1200 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), esp. pp. 357-59. |

| ↑18 | Kathleen Kelly, Performing Virginity and Testing Chastity in the Middle Ages (New York: Taylor & Francis, 2002), 58, suggests that Oda’s survival disturbs Philip’s sense of order. Catherine Mooney, “Clare of Assisi and her Interpreters,” in Gendered Voices: Medieval Saints and their Interpreters, ed. Catherine Mooney (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999), pp. 52-77; and Amy Hollywood, “Inside Out: Beatrice of Nazareth and her Hagiographer,” in Gendered Voices, pp. 78-99, caution us against conflating the male hagiographer’s word and the female saint’s perception of her experiences. |

| ↑19 | Neel, “Origins of the Beguines,” 334-36; Seale, “Ten Thousand Women,” pp. 83-113, examines the development of the Premonstratensian rule for women in depth; Antry and Neel, Norbert and Early Norbertine Spirituality, pp. 194-95 note that Oda could not have lived the kind of cloistered life that Philip’s text implies. |

| ↑20 | Although Dom Ursmer Berlière, “Philippe de Harvengt, abbé de Bonne-Espérance,” Revue Bénédictine 9 (1892): 245, read the text as Philip’s most personal and direct, it is not artless, as Lynsey Robertson has pointed out in “Philip of Harvengt’s “Life of the Blessed Virgin Oda,” p. 59. https://doi.org/10.1484/J.RB.4.02425 |

| ↑21 | Nose-cutting as a punishment for female sexual misconduct appears in medieval western legal texts, but this does not prove that it was often carried out. See Patricia Skinner, “Marking the Face, Curing the Soul? Reading the Disfigurement of Women in the Later Middle Ages,” in Naoë Kukita Yoshikawa, editor, Medicine, Religion and Gender in Medieval Culture. (Suffolk, UK: Boydell & Brewer, 2015), pp. 181-201, esp. pp. 187-89. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781782045137.010; eadem, “The Gendered Nose and its Lack: “Medieval” Nose-cutting and its Modern Manifestations,” Journal of Women’s History 26 (2014): 45-67. https://doi.org/10.1353/jowh.2014.0008; Valentin Groebner, Defaced: the Visual Culture of Violence in the Later Middle Ages, trans. Pamela Selwin, New York 2004, p. 43. Lacey Bonar, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of West Virginia, is completing a dissertation on the cultural history of the human face in the middle ages and included Oda’s story in an unpublished talk at the 56th International Congress on Medieval Studies, entitled “Losing Face, Saving Grace: The Trope of Facial Disfigurement in Saints’ Lives.” |

| ↑22 | Jane Tibbetts Schulenburg, “The Heroics of Virginity: Brides of Christ and Sacrificial Mutilation,” in Mary Beth Rose, ed., Women in the Middle Ages and Renaissance: Literary and Historical Perspectives, Syracuse University Press 1986, pp. 45-49; eadem, Forgetful of Their Sex: Female Sanctity and Society ca. 500-1100, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), esp. pp. 127-75. |

| ↑23 | Augustine is a notable exception, arguing that women should not have to sacrifice their lives for a sin that was not their fault. Schulenburg, “The Heroics of Virginity,” pp. 31-41 and 54-62. |

| ↑24 | Schulenburg, “The Heroics of Virginity,” pp. 56-57 and 67-68, n. 78-82. On Coldingham, see Christiania Whitehead, “A Scottish or English Saint? The Shifting Sanctity of St. Aebbe of Coldingham,” in New Medieval Literatures 19, Philip Knox, Kellie Robertson, Wendy Scase, and Laura Ashe, editors, Cambridge 2019, pp. 1-42. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781787444799.001 |

| ↑25 | Skinner, “The Gendered Nose,” hypothesizes that this suspicion is a reason that Oda was never canonized. |

| ↑26 | In the following century, both St. Elizabeth of Thuringia and St. Margaret of Hungary threatened to cut off their noses to avoid marriages arranged by their families, suggesting that the idea, if not the act itself, was widely known. On disfigurement as escape from marriage, see Karina Marie Ash, Conflicting Femininities in Medieval German Literature (London: Routledge, 2016), p. 9-11; and Martin Porter, “Windows of the Soul”: Physiognomy in European Culture, 1470-1780 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), p. 11. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199276578.001.0001 |

| ↑27 | Robertson, “Philip of Harvengt’s Life of the Blessed Virgin Oda,” pp. 58-62; Antry and Neel, Norbert and Early Norbertine Spirituality,” pp. 192-94; Schulenberg, Forgetful of their Sex, p. 148. |

| ↑28 | Robertson, “Philip of Harvengt’s ‘Life of the Blessed Virgin Oda’,” p. 57, and eadem, “Correspondence and hagiographical works,” p. 133, quotes the text in translation. Migne, PL vol. 203, col. 1366 D. “Leguntur quaedam sanctae mulieres iam nuptae quam virgines cum earum ab hominibus impudicis castitas incursaretur, aliae gladium pectori forti vibramine injecisse, aliea profundo aquarum se immersisse, nonnullae ignibus seu praecipitio interisse, et illorum ausus temerarios morte ultronea praevenisse, sicque venerandum martyrii nomen gloriosae pretio mortis emisse.” |

| ↑29 | Lynsey E. Robertson, “Philip of Harvengt’s “Life of the Blessed Virgin Oda,” p. 57, concludes that the text did not achieve a wide readership, and I would add that that indicates the failure to popularize her cult as well. See also Robertson, , “An Analysis of the Correspondence and Hagiographic Works of Philip of Harvengt,” Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, University of St. Andrews, 2007, pp. 128-29. http://hdl.handle.net/10023/526. Accessed 11 March 2021. |

| ↑30 | Philip of Harvengt, Opera, J.-P. Migne, PL, vol. 203, Paris, 1855; Robertson, “Correspondence and Hagiographic Works of Philip of Harvengt,” pp. 128-29. |

| ↑31 | Peter Fuhring, “The Stocklist of Johannes Galle, print publisher of Antwerp, and print sales from old copperplates in the seventeenth century,” Simiolus 39 (2017): 225-313 documents the vast collection of copperplates passed down to Joannes Galle from his father and uncles. Included are images of saints of different religious orders; see also Appelmans and Janssen, 125-31 and notes 1 and 2. |

| ↑32 | Previously associated with Martin Pepijn, the designs have recently been attributed to Pieter Jode I. See Veldman, Ilja M; Ger Luijten; and F W H Hollstein, The New Hollstein Dutch & Flemish Etchings, Engravings and Woodcuts, 1450-1700, vol. 32, The De Jode Dynasty, Part VII. Marjolein Leesburg, compiler; ed. Simon Turner (Atlanta, GA: Sound & Vision, 2020), p. xlviii. |

| ↑33 | Johannes Chrysostomus van der Sterre, Vita Sancti Norberti, Canonicorum Praemonstratensium Patriarchae, Antverpiae Apostoli, Archiepiscopi Magdeburgensis ac totius Germaniae Primatis, Antwerp, 1622. On van der Sterre, see Herman Vanderlinden, “Sterre (Jean-Chrysostome vander)”, Biographie Nationale de Belgique, vol. 23 (Brussels, 1924), 815–16; and Barbara Haeger, “Abbot Van der Sterre and St. Michael’s Abbey. The Restoration of its Image, and its Place in Antwerp”, in Sponsors of the Past: Flemish Art and Patronage, 1550–1700, edited by H. Vlieghe and K. Van der Stighelen (Turnhout: Brepols, 2005), pp. 157-79. |

| ↑34 | Karen L. Bowen, “Workshop Practices in Antwerp: The Galles,” Print Quarterly 26 (2009): 123-42; Fuhring, “The Stocklist of Johannes Galle,” pp. 228-34. |

| ↑35 | Appelmans and Janssen, 125. |

| ↑36 | Appelmans and Janssen, 125-31. The trees were initially printed by Karel van Mallery, who was married to the Galle brothers’ sister Catherine. |

| ↑37 | Simon Ditchfield, “Catholic Reformation and Renewal,” in The Oxford Illustrated History of the Reformation, edited by Peter Marshall, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), p. 156, notes the critical role played by etchings from Antwerp in the global proliferation of the cult of saints; David Freedberg, “The Representation of Martyrdoms During the Early Counter-Reformation in Antwerp,” Burlington Magazine 118/876 (March 1976): 128-38, esp. 128-29 and n. 1-3, attributes much of the proliferation of altarpieces depicting saints and martyrdoms to the aftermath of iconoclasm in Antwerp in 1566 and 1581. |

| ↑38 | Libertus de Pape, Summaria cronologia insignis ecclesiae Parchensis ordinis Praemonstratensis sive prope muros oppidi Lovaniensis, Leuven, 1662, pp. 437-39, describes the destruction and the repairs undertaken by Abbot Maes; J.E. Jansen, L’Abbaye norbertine du Parc-le-Duc: huit siècles d’éxistence, 1129-1929 (Malines/Mechelin: H. Dessain, 1929), pp. 46-47 summarizes these events. |

| ↑39 | Maes’s writings included an unpublished chronicle of the abbey up to 1635, Archives Anciennes de l’abbaye du Parc (AAAP) MS VII, 3, which would be incorporated into the work of his successor Libertus de Pape, Summaria cronologia. |

| ↑40 | Académie Royale des sciences, des lettres, et des beaux-arts de Belgiques, Biographie nationale (Brussels: H. Thiry-Van Buggenhoudt, 1894), vol. 13, pp. 137-38; E. van Even, Louvain Monumental (Louvain: Fonnteyn, 1860), pp. 470-71; J.E. Jansen, L’abbaye norbertine du Parc-le-Duc, pp. 219-37; Quirin Nols, Masius, abbé de Parc, 1635-1647: Sa vie. Ses rapports avec les partisans de Jansénius (Brussels: Misch et Thron, 1908-09). |

| ↑41 | Van Even, Louvain Monumental, p. 246. See also Lecocq and Shortell, “Les vitraux de l’abbaye de Parc,” and Rambaut, Vanderauwera, Shortell, Jarron, and Mestdagh, “The Masterpiece of Jean de Caumont returns to Park.” |

| ↑42 | AAAP MS R VIII 50, fol. 32-34 vo. Félix Maes, O. Praem., “De oude glasramen van de abdij van’t Park te Heverlee,” Mededelingen van de Geschied- en Oudheidkundige Kring voor Leuven en Omgeving XII/1, 1972, pp 3-34, analyzes the accounts, but with some errors; his conclusions were summarized by Jean Helbig in “Anciennes Verrières de l’Abbaye de Parc,” Bulletin des Musées Royaux d’Art et d’Histoire, Brussels, 6th series XXX, 1958, pp. 71-82. |

| ↑43 | The placement of many of the panels can be gleaned from Maes’s account book, where he gives the date, location, and a few of the subjects of panels received, AAAP MS R VIII 50, fol. 32-34 vo. Records of burials in the cloister in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries also reference some of the subjects of the windows in describing the locations of graves, AAAP MS R VIII 2, and in Raphaël Van Waefelghem, Le nécrologe de l’abbaye du Parc, Analectes de l’ordre de Prémontré, 1 (Brussels 1908). |

| ↑44 | Based on poem by Canon Eustache de Pomreux du Sart. See Lecocq and Shortell, “Les vitraux de l’abbaye de Parc,” pp. 13-14 and n. 40. |

| ↑45 | Two such panels have survived and show that this plan was carried out for some of the subsequent abbots. One panel with the arms of Abbot Libertus de Pape, dated 1666, was returned to Park Abbey in 1971, while that of Abbot Hieronymus de Waerseghere, dated 1718, was at the Corcoran Gallery of Art and illustrated in Stained Glass before 1700 in American Collections, Corpus Vitrearum Checklist II, Midatlantic and Southeastern Seaboard States, ed. Madeline Caviness and Jane Hayward, Studies in the History of Art 23 (1987): 31. |

| ↑46 | Corine Schleif, “Men on the Right – Women on the Left: (A)symmetrical Spaces and Gendered Places,” in Women’s Space: Patronage, Place, and Gender in the Medieval Church, ed. Virginia Chieffo Raguin and Sarah Stanbury (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2005), pp. 207-49, esp. 219-21 and 224-27, brings a number of different sources to bear on the gendered significance of spaces in religious art and architecture. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780791483718-010; Schleif drew partly on the work of Josef Sauer, Symbolik des Kirchengebaudes und seine Ausstattung in der Auffassung des Mittelalters (Freiburg: Herder, 1942, reprinted Munster: Mehren und Hobbeling, 1964), pp. 87-96; Otto Nussbaum, “Die Bewertung von Rechts und Links in der romischen Liturgie,” ]ahrbuch fur Antike und Christentum 5 (1962): 158-71; and Friedrich Mobius, “Basilikale Raumstruktur im Feudalisierungsprozess: Anmerkungen zu einer ‘Ikonologie der Seitenschiffe,’ ” Kritische Berichte 7, no. 2/3 (1979): 5-17. 19. See also Richard Krautheimer, Early Christian and Byzantine Architecture (Hamondsworth: Penguin, 1986), esp. 218-19. |

| ↑47 | I thank Tim Ayers for his suggestions about this connection. |

| ↑48 | Antry and Neel, Norbert and Early Norbertine Spirituality, pp. 165-91, offer an analysis and translation of an early treatise on the need for learning through devotional reading among Premonstratensian clerics, Philip of Harvengt’s “On the knowledge of Clerics.” Statuta Candidissimi & Canonici Ordinis Praemonstratensis renovata, the order’s statutes revised under the direction of Jan Druys, Abbot of Park, and approved in 1630, attests to the continued practice. Other documents that incidentally mention reading benches include account books (AAAP MS R VIII 50, fol. 32) and necrologies (AAAP MS R 8 40). |

| ↑49 | On the Siege of Leuven and its aftermath, see J.E. Jansen, L’abbaye norbertine du Parc-le-Duc, p. 46; Quirin Nols, Masius, abbé de Parc, pp. 14-15. |

| ↑50 | Jansen, L’abbaye norbertine du Parc-le-Duc, p. 43 and n. 1. |

| ↑51 | Libertus de Pape, Summaria Cronologica, pp. 441-45. |

| ↑52 | The other martyrs included Hroznata of Oveneč, who died after being kidnapped and imprisoned by knights in Tepl, Bohemia, who disputed his monastery’s possessions, in 1217; Eelko Liaukama, abbot of Lidlum in Holland, said to have been beaten to death by monks who resented his attempts to enforce discipline on 22 March 1322. |

| ↑53 | Freedberg, “Representation of Martyrdoms,” esp. 128-30 and 135-38. |

| ↑54 | Romana Zacchi, “Words and Images: Verstegan’s ‘Theater of Cruelties’,” in Richard Rowlands Verstegan: A Versatile Man in an Age of Turmoil, edited by R. Zacci and M. Morini, (Turnhout: Brepols, 2012). https://doi.org/10.1484/M.LMEMS-EB.5.112580 |

| ↑55 | On the Venerable English College and its decoration, see Carol M. Richardson, “Durante Alberti, the Martyrs’ Picture, and the Venerable English College, Rome,” Papers of the British School at Rome 73 (2005): 223-63, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0068246200003032; F. Gasquet, A History of the Venerable English College, Rome (London, Longmanns, Green and Co., 1920). |

| ↑56 | Howard Louthan, Converting Bohemia: Force and Persuasion in the Catholic Reformation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) 2009, pp. 34-46; Rosemary Sands, “The Translation of St. Norbert’s Remains to Prague in 1627: True account of a letter sent by St. Michael’s of Antwerp to the Canons Regular of the Monastery of Saint Norbert of Madrid,” Communicator: The English Speaking Circary of the Order of Prémontré 35/2 (2018): 11-15. |

| ↑57 | Robertson, “Life of Blessed Virgin Oda,” p. 57. Frederika Elizabeth Bain, Dismemberment in the Medieval and Early Modern English Imagery: The Performance of Difference (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2021), pp. 74-75. Groebner, Defaced, p. 12. For St. Agatha, see especially Martha Easton, “Saint Agatha and the Sanctification of Sexual Violence,” Studies in Iconography 16 (1994): 83-118; and Madeline H. Caviness, Visualizing Women in the Middle Ages: Sight, Spectacle, and Scopic Economy (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), pp. 83-123. |

| ↑58 | Bain, Dismemberment, pp. 73-77; Groebner, Defaced, p. 77. |

| ↑59 | The commission for this sculpture for St. Norbert Abbey, De Pere, Wisconsin, created by ALBL, a woodcarving studio for sacred art in Oberammergau, Germany, was based on Oda’s story in the Premonstratensian Hagiologon. Personal correspondence with Fr. Stephen James Rossey, O.Praem. |

| ↑60 | The nose, which exudes a thick fluid, protrudes from the body, and has visible openings, can be associated with male or female sexual organs as Bain, Dismemberment, p. 73, points out. Bain cites Jürgen Frembgen, “Honour, Shame, and Bodily Mutilation: Cutting off the Nose among Tribal Societies in Pakistan,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (Third Series) 16/3 (November 2006): 243-45, to argue that this association holds true across cultures. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1356186306006444 |

| ↑61 | Easton “Saint Agatha,” 83-118; Caviness, Visualizing Medieval Women, pp. 83-123. |

| ↑62 | Johannes Chrysostom van der Sterre, Natales Sanctorum Candidissimi Ordinis Praemonstratensis, Antwerp, 1625, pp. 55-56. The full text reads: Apud Bincæium Hannoniæ oppidum iuxta Bonæ-Spei Coenobium, Natalis B. Odae Virginis Ordinis Praemonstratensis: Quae miro Stratagemate mundi elusis amoribus, proque integritatis fide Sponso suo coelesti data, plurima perpessa; post contextas sibi arias patientiae coronas, cum Virginibus sacris egregia sanctitate praefuisset; ad percipiendam inviolatae virginitatis Lauream emigravit. |

| ↑63 | New York Historical Society, McKim, Mead and White Archives, box 507; Wayne Craven, Gilded Mansions: Grand Architecture and High Society, (New York: Norton, 2009, 30, p. 81; Shortell, “Visionary Saints in the Gilded Age,” p. 246. |

| ↑64 | Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University. Stanford White letterpress books, volume 19, 1898, correspondence between Stanford White and Godfrey von Kopp. |

| ↑65 | Shortell, “Visionary Saints in the Gilded Age,” 245-51. 150,000 francs in 1898 would be worth about $800,000 – $1,000,000 today. |

| ↑66 | AAP, HD 87, 1-28. |

| ↑67 | Shortell, “Afterlife,” pp. 247-49. |

| ↑68 | “How American Millionaires Live,” The Harmsworth London Magazine vol. 7 (1901-1902), p. 86; Florence N. Levy, “The Residence of Mr. William C. Whitney,” The Art Interchange vol. 44 no. 1 (January 1900), pp. 82-85. |

| ↑69 | Details of Whitney’s entertainments and the house in which they took place appeared in the Society pages of the New York Times: “Whitney Ball a Spectacle of Splendor,” 5 January 1901, p. 3; “Society Applauds at Mr. Whitney’s Ball,” 18 December 1901, p. 9; and “W.C. Whitney Gives Ball,” 19 December 1903, p. 9. |

| ↑70 | Meryl Secrest, Duveen: A Life in Art (Westminster, MD: Knopf, 2004), pp. 52 and 74; Corcoran Gallery of Art, From Antiquity to Impressionism, Washington, DC, 2001, esp. p. 18; and Illustrated Handbook of the W.A. Clark Collection (Washington, DC: 1928), esp. p. 134. According to the registrar’s office at the Corcoran Gallery, Clark destroyed his records (personal correspondence with author, 1987). |

| ↑71 | Bill Dedman and Paul Clark Newell, Jr., Empty Mansions: The Mysterious Life of Huguette Clark and the Spending of a Great American Fortune (New York: Ballantine, 2013), pp. 11-12. |

| ↑72 | American Art Association, The Magnificent Furnishings, Paintings & Objects of Art Removed from the Residences Rockwood Hall, Tarrytown, N.Y., and No. 689 Fifth Avenue, New York City. To be sold by order of the executors of the Estate. Sale Number 1777, on Public Exhibition from Wednesday, November Fourteenth. The Anderson Galleries, Inc., Park Avenue and 59th Street, New York. November 19-24, 1923, #1206. |

| ↑73 | American Art Association, Illustrated Catalogue of the Artistic Furnishings and Interior Decorations of the Residence No. 121 East Twenty-First Street, New York City…Estate of the late Stanford White [sale cat. November 27, 1907], New York, 1907, n.p., nos. 499-508. |

| ↑74 | An annotated copy of the Illustrated Catalogue of the Estate of the late Stanford White lists Hearst as one of the buyers. Madeline H. Caviness, “The Germanophilia of William Randolph Hearst and the Fate of his Collection,” in Collections of Stained Glass and their Histories, pp. 175-92. |